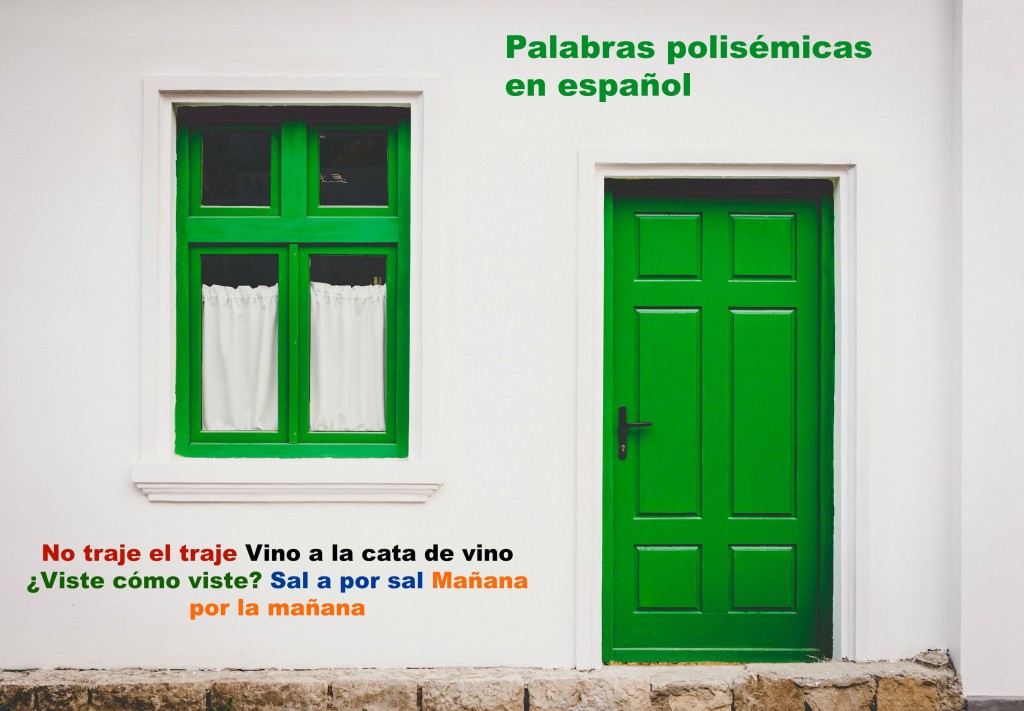

Palabras polisémicas en español – Polysemy in Spanish: word choice matters

- Palabras polisémicas en español

Una palabra es polisémica si tiene varios significados pero un único significante. En español ocurre a menudo que se utiliza la misma palabra dos veces en la misma oración, dando lugar a frases bastante curiosas que pueden llamar la atención del estudiante de español. He aquí algunos ejemplos ¿Se te ocurre alguno más? ¡Compártelo con nosotros!

Polysemy is the existence of several meanings in a single word. In Spanish happens that the same word is used twice in the same sentence, leading to rather funny phrases that can be somewhat confusing for the student of Spanish. Here are some examples. Can you think of more sentences in Spanish like these? Share it with us!

No traje el traje – I didn’t bring the suit

Mañana por la mañana – Tomorrow morning

Olvidé la bolsa en la Bolsa – I forgot my bag in the stock exchange

¿Se cura el cura? – Is the priest healing?

Te he dado el dado – I have give you the dice

Me regaló un imán del Imán para la nevera – He gave me a magnet of the Iman for the fridge

Estoy sentado en el banco frente al banco – I am sitting on the bench in front of the bank

Un mono muy mono vestido con un mono de trabajo – A very cute monkey dressed with overalls

El chico bajo es el que toca el bajo – The short guy is the one playing the bass

Bota esa bota – Throw away that boot

Sal a por sal, por favor – Get out to buy some salt, please

¿Viste cómo viste? – Did you see how she dress?

Vino a la cata de vino – He came to the wine tasting

¿Pero existe una palabra para eso?

Aprender un idioma nuevo puede ser un proceso lleno de altibajos. A veces el estudiante de una segunda lengua se siente capaz de hablar sobre cualquier tema y en otras ocasiones apenas parece capaz de balbucear todas esas palabras de uso común que lleva tiempo aprendiendo.

Aprender un idioma nuevo puede ser un proceso lleno de altibajos. A veces el estudiante de una segunda lengua se siente capaz de hablar sobre cualquier tema y en otras ocasiones apenas parece capaz de balbucear todas esas palabras de uso común que lleva tiempo aprendiendo.

Pero no hay que desesperar: todo forma parte de un enriquecedor proceso de aprendizaje hasta alcanzar un conocimiento alto de esa segunda lengua.

Sin embargo, en español, aunque alcancemos un grado de dominio casi nativo, existe un sinfín de palabras que nunca jamás aprenderemos ya que su uso es tan reducido que apenas son útiles para los nativos.

En el español tenemos palabras para cosas tan precisas que es imposible no sorprenderse al descubrirlas. La mayoría sirven para definir una acción o cosa tan concreta que se puede pasar una vida entera sin tener la menor necesidad de utilizarlas.

Hoy vamos a compartir una breve lista de estas palabras raras y sus pertinentes definiciones del Diccionario de la Real Academia que, aunque poco usadas, merecen ser recordadas de vez en cuando.

-Companaje

(De con y pan, en b. lat. companagĭum).

1. m. Comida fiambre que se toma con pan, y a veces se reduce a queso o cebolla.

-Amusgar

(Del lat. tardío amussicāre, y este del lat. mussāre ‘murmurar, cuchichear’).

1. tr. Dicho de un caballo, de un toro, etc.: Echar hacia atrás las orejas en ademán de querer morder, tirar coces o embestir. U. t. c. intr.

2. tr. Entrecerrar los ojos para ver mejor.

3. prnl. avergonzarse.

-Carraña

1. f. Ar. Ira, enojo.

2. f. Ar. Persona propensa a estas pasiones.

-Gulusmear

1. intr. Andar oliendo o probando lo que se guisa. U. t. c. tr.

2. intr. Curiosear, husmear. U. t. c. tr.

-Birlí

1. m. Impr. Parte inferior que queda en blanco en las páginas de un impreso.

2. m. Impr. Ganancia que por ello obtiene el impresor.

3. m. Impr. Ganancia que consigue aprovechando para distinta tirada la composición ya hecha.

-Barbián

(Del caló barbán, aire).

1. adj. coloq. Desenvuelto, gallardo, arriscado. U. t. c. s.

-Jipiar

(De la onomat. jip, jip, del gemido).

1. intr. Hipar, gemir, gimotear.

2. intr. Cantar con voz semejante a un gemido.

-Jauto

(De or. inc.).

1. adj. Ar. Insípido y sin sal.

¿Conoces más palabras raras en español? Compártelas en los comentarios.

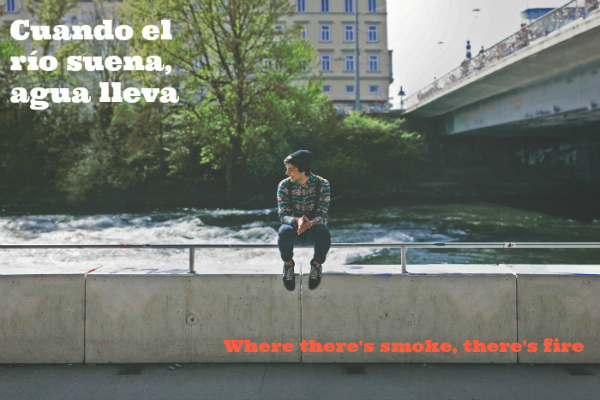

Dichos españoles y sus equivalentes en inglés / Spanish idioms and their English equivalents

Como todos los idiomas, el español acumula muchas frases hechas y refranes que sirven de reflejo de las ideas y la filosofía popular de los españoles. El refranero español es uno de los más completos que se conocen en el mundo, con casi 100.000 refranes registrados. Pero además las frases hechas y los refranes son un recurso muy útil para los estudiantes de español ya que el uso de refranes es una parte consustancial de la forma de hablar habitual de los hispanohablantes.

Para abrir boca aquí os presentamos algunos de los refranes españoles más utilizados, su traducción literal y su equivalente en inglés:

Like every language does, Spanish accumulates many idioms that reflect the Spanish popular way of thinking. “El refranero español” (The Spanish book of proverbs) is one of the most complete in the world, with nearly 100,000 registered idioms and proverbs. But also, they are very useful for students of Spanish because they are an essential part of the popular and informal way of speaking.

Here you have a short list with some of the most used and useful Spanish proverbs and idioms, their literal translations and their equivalent in English:

Del dicho al hecho hay un trecho.

Literal translation: From the spoken words to the facts there is a long way.

English equivalent: Easier said than done a stretch.

A buen entendedor, pocas palabras bastan.

Literal translation: To the good listener, few words are enough.

English equivalent: A word is enough to the wise.

Más vale pájaro en mano que ciento volando.

Literal translation: A bird in the hand is worth hundred flying.

English equivalent: A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

Cuando hay hambre, no hay pan duro.

Literal translation: When you are hungry, there is no hard bread.

English equivalent: Beggars can’t be choosers.

Dios los cría y ellos se juntan.

Literal translation: God raises them and they get together.

English equivalent: Birds of a feather flock together.

No vendas la piel del oso antes de cazarlo.

Literal translation: Don’t sell the bear’s skin before you get to hunt it.

English equivalent: Don’t count your chickens before they are hatched.

No te lo juegues todo a una sola carta.

Literal translation: Don’t bet all to one card.

English translation: Don’t put all your eggs in one basket.

Hecha la ley, hecha la trampa.

Literal translation: Done the law, done the trick.

English equivalent: Every law has its loophole.

Por un perro que maté, mataperros me llamaron

Literal translation: I killed a dog and now they call me dog killer.

English equivalent: Give a dog a bad name and hang it.

Dios aprieta pero no ahoga.

Literal translation: God squeezes but does not choke.

English equivalent: God tempers the wind to the shorn lamb.

Vísteme despacio que tengo prisa.

Literal translation: Dress me slowly that I’m in a hurry.

English equivalent: More haste, less speed.

Lo cortés no quita lo valiente.

Literal translation: Politeness doesn’t override bravery.

English equivalent: Politeness costs nothing.

En casa del herrero, cuchillo de palo.

Literal translation: In the Blacksmith’s home they use a wooden knife.

English equivalent: The shoemaker’s son always goes barefoot.

Cuando el río suena, agua lleva.

Literal translation: When you hear the river it’s because it carries water.

English equivalent: Where there’s smoke, there’s fire.

Debido a su gran importancia, pero también porque se trata de una parte del español que combina cultura y lengua de forma tan interesante como entretenida, el Instituto Cervantes de Nueva York ofrece a partir del 21 de junio un curso especializado para que los estudiantes se familiaricen con algunos de los refranes más comunes del español y sepan identificar las mejores ocasiones para utilizarlos.

Because of its great importance, but also because it is a part of the Spanish culture that combines entertainment and language, Instituto Cervantes New York offers a specialized course to familiarize students with some of the most commonly used Spanish idioms and proverbs.

La palabra que se puede decir pero no escribir / The word that can be pronounced but not written

Hace un tiempo, el blog español “Un arácnido, una camiseta”, dedicado al estudio lingüístico, descubrió una extraña curiosidad ortográfica del español. Un lector del blog hizo la siguiente consulta a uno de los gestores del blog: “¿Cómo se escribe el imperativo de salirle en la segunda persona del singular?” .

Desde el blog trasladaron la pregunta a la Real Academia Española, que respondió que ese imperativo más el pronombre enclítico es “sal+le”, pero que la ortografía del español no contempla esa posibilidad de escritura, porque el resultado es una elle: salle, y esa elle no refleja la pronunciación deseada. Esta es la respuesta exacta de la RAE:

La interpretación forzosa como dígrafo de la secuencia gráfica ll en español hace imposible representar por escrito la palabra resultante de añadir el pronombre átono le a la forma verbal sal (imperativo no voseante de segunda persona de singular del verbo salir), oralmente posible si, por ejemplo, ordenáramos a alguien salir al paso o al encuentro de otra persona aludida con el pronombre le: [sál.le al páso], [sál.le al enkuéntro].Puesto que los pronombres átonos pospuestos al verbo han de escribirse soldados a este, sal + le daría por escrito salle, cuya lectura sería forzosamente [sá.lle], y no [sal.le].

Nos encontramos entonces con el que tal vez sea el único funcionamiento defectuoso de la ortografía española. Una palabra que existe gramaticalmente y se puede pronunciar, y que sin embargo no se puede escribir. ¿Qué hará la RAE para solucionarlo?

Otras curiosidades del español

¿Sabías que el español es el único idioma que abre y cierra las interrogaciones y las exclamaciones? Los signos de interrogación y exclamación invertidos fueron alentados por la Real Academia Española y no parecen haber sido imitados por otros idiomas.

¿Sabes lo que es un firulete? La palabra «pedigüeñería» tiene los cuatro firuletes que un término puede tener en nuestro idioma: la virgulilla de la ñ, la diéresis sobre la ü, la tilde del acento y el punto sobre la i.

¿Sabes que el español es uno de los idiomas más fonéticos del mundo? Una de las grandes ventajas para los estudiantes de español es que si saben cómo se escribe una palabra, casi siempre pueden saber cómo se pronuncia (aunque la regla no se cumple al contrario).

¿Sabes que hay algunas palabras en español que se pueden deletrear de dos maneras diferentes? Aquí tienes algunos ejemplos, aunque, por supuesto, una de ellas suele ser más recomendable que la otra. ¿Adivinas cuál?

•Murciélago y murciégalo

•Séptimo y sétimo

•Septiembre y setiembre

•Transporte y trasporte

•Obscuro y oscuro

•Substancia y sustancia

•Mayonesa y mahonesa

Did you know that in Spanish there is a word that can be pronounced but not written? A while ago, the Spanish blog «Una araña, una camiseta», specialized in linguistics, found a very curious Spanish orthography bug. A blog reader asked the following query to one of the managers of the blog:

«How’s the second person singular imperative of the verb “salirle” (to run into someone or something intentionally) written?”

The editors of the blog forwarded the question to the Real Academia de la Lengua Española, and they replied that this imperative form plus the pronoun “le” results in «sal+le», but the spelling of Spanish does not contemplate the possibility of writing this word, because the result would be a double “L”, whose reading would necessarily be [sá.lle], like the sound of “calle”, and not [sal.le].

Probably this case is the only bug in Spanish orthography: a word that exists and can be pronounced, but cannot be written. What will the RAE do to fix it?

Other curiosities:

–Spanish uniquely uses inverted question marks and exclamation points. The upside-down marks as in the sentences «¿Quién eres?» (Who are you?) and «¡Ayúdame!» (Help me!) were encouraged by the Real Academia Española and do not appear to have been copied by other languages.

-Do you know what a “firulete” is? The Spanish word «pedigüeñería» is unique because it has the four “firuletes” that exist in Spanish: the “virguilla” on the “ñ”, the umlaut on “ü”, the accent on the “í” and the dot on the “i”.

-Did you know that Spanish is one of the world’s most phonetic languages? One of the best things for students of the Spanish language is that if they know how a word is spelt, they can almost always know how it is pronounced (although the reverse isn’t always right).

-Did you know that there are some words in Spanish that can be spelt in two different ways? Here you have some examples (but of course one of them is more recommendable than the other. Can you guess which one?)

•Murciélago y murciégalo

•Séptimo y sétimo

•Septiembre y setiembre

•Transporte y trasporte

•Obscuro y oscuro

•Substancia y sustancia

•Mayonesa y mahonesa

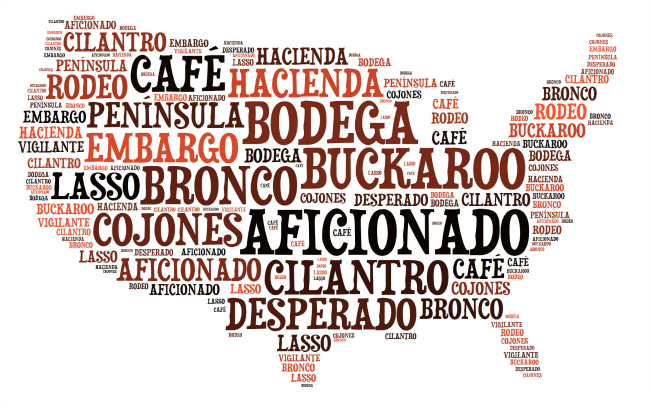

10 palabras procedentes del español que usas en inglés / 10 Spanish Words You Might Not Know You’re Using

Probablemente el inglés sea el idioma que más palabras y términos ha exportado a otras lenguas, sin embargo el proceso inverso también se produce. Especialmente destacable es la influencia del español en el inglés de los Estados Unidos. Tanto por motivos históricos como por la creciente comunidad hispanohablante en Estados Unidos, es inevitable que ambas lenguas tomen prestadas palabras y expresiones la una de la otra. Veamos algunas de las más comunes:

-Aficionado. Significa exactamente lo mismo que en español. En Nueva York podrás encontrar a un gran número de wine aficionados.

-Bodega. Esta palabra la oirás principalmente en Nueva York y tiene un significado ligeramente diferente ya que se refiere a una tienda de comestibles de barrio. En el resto del país no la han adoptado y se utiliza la acepción inglesa corner store.

-Buckaroo. El origen de esta curiosa palabra que se usa como sinónimo de cowboy está en la errónea pronunciación de vaquero. Aunque no se utiliza demasiado, se puede ver empleada en algunas películas y novelas.

-Cilantro. Cada vez se utiliza más el término en español para referirse a una de las especias más utilizadas en la comida norteamericana, aunque el inglés tiene el término coriander.

-Cojones. En inglés se utilizan los castizos cojones en su acepción de valor o coraje, desprovista del matiz soez que puede tener en español. Curiosamente esta palabra está especialmente valorada en el mundo político estadounidense.

-Desperado. Un desperado es para los americanos un criminal temerario y audaz que proliferaba mucho durante los primeros años del salvaje oeste americano. Su origen está en la palabra española desesperado.

-Lasso. En Estados Unidos es una cuerda larga de cuero u otro material con un nudo corredizo en un extremo, utilizado para amarrar caballos, ganado, etc. y viene de la española lazo.

-Mano a mano. Esta expresión española se utiliza en inglés para referirse a una “confrontación directa o un duelo entre dos partes”.

-Rodeo. El deporte favorito de los tejanos debe su nombre a que en las colonias españolas de América el rodeo fue el proceso utilizado por los vaqueros para reunir el ganado.

-Vigilante. En Estados Unidos un vigilante es cualquiera que se tome la ley por su mano para vengar algún crimen anterior.

Hay muchas más palabras y expresiones del español que han encontrado acomodo en el inglés. ¿Se os ocurre alguna más?

Without a doubt, English is the language that most words and terms has exported to other languages, but it’s a 2-way street and English speakers also use words imported from other languages. Especially noteworthy is the influence of the Spanish in the US English. The reasons for that are several: the presence of Spaniards during past centuries left an undeniable legacy, but also the growing of the Latin community in the United States is having a deep impact on the way people talk. It is inevitable that both languages borrow words and expressions from each other. Here are some of the most common Spanish words English speakers might not know they’re using:

– Aficionado. It means exactly the same thing in Spanish. In New York you can find a large amount of wine aficionados, for example.

-Bodega. You will hear this word mostly in New York and has a slightly different meaning from the Spanish word since it’s referred to a grocery store and not only to a liquor store. In the rest of the US bodega has not been adopted.

-Buckaroo. The origin of this funny word -used as a synonym for cowboy of de Great Basin and California Region- is in the wrong pronunciation of the Spanish word vaquero.

-Cilantro. This a interesting case. Although English has its own word for this herb (coriander), the use of the Spanish word cilantro is becoming more and more popular.

-Cojones. This powerful and sometimes rude Spanish word is used in English in the sense of value or courage. Interestingly this word is particularly popular in the American political world.

-Desperado. This word was the name given to these audacious criminals who proliferated greatly during the early years of the American Wild West. Its true origin is in the Spanish word desesperado which means desperate.

-Lasso. This is the word used in US to define a long string of leather or other material with a noose at one end, used mainly to tie horses , cattle, etc… You can find its true origin in the Spanish word lazo, meaning tie.

– Mano a mano. This Spanish phrase is used in English to refer to a «direct confrontation or a duel between two parties.» Its literal translation is “hand to hand”.

– Rodeo. The favorite sport of Texans owes its name to the Spanish colonies in America. The rodeo was the process used by cowboys to herd the cattle.

-Vigilante. In the United States a vigilante is anyone who takes the law into his own hands and fights against the crime. In Spanish vigilante means watchman.

There are many more Spanish words and expressions you can find in the English language. Can you think of any more?