The benefits of Spanish as a second language

Book a free demo class now

In the age of global business, the value of employees being able to speak more than one language has increasingly been highlighted over the last few years. Multilingual employees earn more money and have «practical benefits in a globalized economy».

Despite the fact that The United States is now the world’s second largest Spanish-speaking country after Mexico, many American people still monolingual.

Truth be told, being bilingual or mulitlingual has also many personal benefits. From being better at multi-tasking to decision making, sharper reasoning, holding off the onset of Alzheimer and being able to see or read about situations from a different perspective or cultural point of view.

Unfortunately many still don’t see the real need for a native English speaker to go out of their comfort zone and learn a second language.

Comfort is easy. We fear uncertainty and so we seek to cushion ourselves in artificial climate-controlled boxes safe from unwanted intrusions. But this is unfortunate. Personal discovery and personal development happen only outside our comfort zone.

When it comes to language learning we create tons of excuses to avoid getting out of our comfort zone: «I’m too old to learn a second language», «I haven’t enough memory to study,» «I’ll sound silly speaking another language,» «They will laugh at me,» etc. But if we take a moment to look back, we see that our life is a sequence of firsts. There’s a first time for everything. And we’ve always felt fear and uncertainty. It’s time to beat language-learning frustration, reach your goals and enjoy a new world of opportunities.

Book a free demo class now

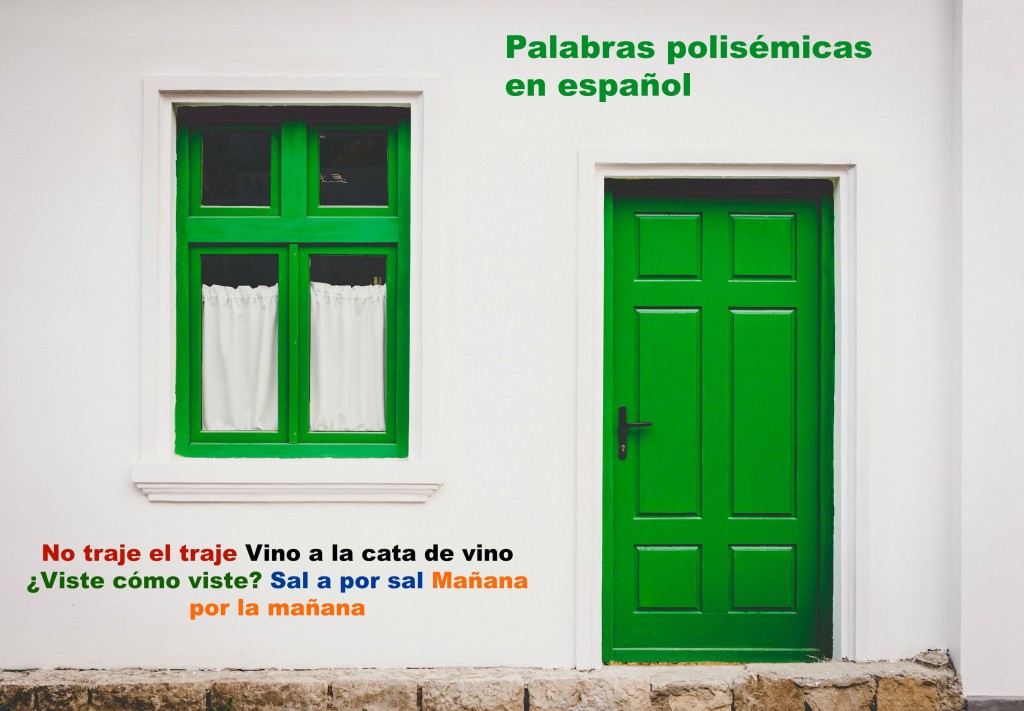

Palabras polisémicas en español – Polysemy in Spanish: word choice matters

- Palabras polisémicas en español

Una palabra es polisémica si tiene varios significados pero un único significante. En español ocurre a menudo que se utiliza la misma palabra dos veces en la misma oración, dando lugar a frases bastante curiosas que pueden llamar la atención del estudiante de español. He aquí algunos ejemplos ¿Se te ocurre alguno más? ¡Compártelo con nosotros!

Polysemy is the existence of several meanings in a single word. In Spanish happens that the same word is used twice in the same sentence, leading to rather funny phrases that can be somewhat confusing for the student of Spanish. Here are some examples. Can you think of more sentences in Spanish like these? Share it with us!

No traje el traje – I didn’t bring the suit

Mañana por la mañana – Tomorrow morning

Olvidé la bolsa en la Bolsa – I forgot my bag in the stock exchange

¿Se cura el cura? – Is the priest healing?

Te he dado el dado – I have give you the dice

Me regaló un imán del Imán para la nevera – He gave me a magnet of the Iman for the fridge

Estoy sentado en el banco frente al banco – I am sitting on the bench in front of the bank

Un mono muy mono vestido con un mono de trabajo – A very cute monkey dressed with overalls

El chico bajo es el que toca el bajo – The short guy is the one playing the bass

Bota esa bota – Throw away that boot

Sal a por sal, por favor – Get out to buy some salt, please

¿Viste cómo viste? – Did you see how she dress?

Vino a la cata de vino – He came to the wine tasting

¿Pero existe una palabra para eso?

Aprender un idioma nuevo puede ser un proceso lleno de altibajos. A veces el estudiante de una segunda lengua se siente capaz de hablar sobre cualquier tema y en otras ocasiones apenas parece capaz de balbucear todas esas palabras de uso común que lleva tiempo aprendiendo.

Aprender un idioma nuevo puede ser un proceso lleno de altibajos. A veces el estudiante de una segunda lengua se siente capaz de hablar sobre cualquier tema y en otras ocasiones apenas parece capaz de balbucear todas esas palabras de uso común que lleva tiempo aprendiendo.

Pero no hay que desesperar: todo forma parte de un enriquecedor proceso de aprendizaje hasta alcanzar un conocimiento alto de esa segunda lengua.

Sin embargo, en español, aunque alcancemos un grado de dominio casi nativo, existe un sinfín de palabras que nunca jamás aprenderemos ya que su uso es tan reducido que apenas son útiles para los nativos.

En el español tenemos palabras para cosas tan precisas que es imposible no sorprenderse al descubrirlas. La mayoría sirven para definir una acción o cosa tan concreta que se puede pasar una vida entera sin tener la menor necesidad de utilizarlas.

Hoy vamos a compartir una breve lista de estas palabras raras y sus pertinentes definiciones del Diccionario de la Real Academia que, aunque poco usadas, merecen ser recordadas de vez en cuando.

-Companaje

(De con y pan, en b. lat. companagĭum).

1. m. Comida fiambre que se toma con pan, y a veces se reduce a queso o cebolla.

-Amusgar

(Del lat. tardío amussicāre, y este del lat. mussāre ‘murmurar, cuchichear’).

1. tr. Dicho de un caballo, de un toro, etc.: Echar hacia atrás las orejas en ademán de querer morder, tirar coces o embestir. U. t. c. intr.

2. tr. Entrecerrar los ojos para ver mejor.

3. prnl. avergonzarse.

-Carraña

1. f. Ar. Ira, enojo.

2. f. Ar. Persona propensa a estas pasiones.

-Gulusmear

1. intr. Andar oliendo o probando lo que se guisa. U. t. c. tr.

2. intr. Curiosear, husmear. U. t. c. tr.

-Birlí

1. m. Impr. Parte inferior que queda en blanco en las páginas de un impreso.

2. m. Impr. Ganancia que por ello obtiene el impresor.

3. m. Impr. Ganancia que consigue aprovechando para distinta tirada la composición ya hecha.

-Barbián

(Del caló barbán, aire).

1. adj. coloq. Desenvuelto, gallardo, arriscado. U. t. c. s.

-Jipiar

(De la onomat. jip, jip, del gemido).

1. intr. Hipar, gemir, gimotear.

2. intr. Cantar con voz semejante a un gemido.

-Jauto

(De or. inc.).

1. adj. Ar. Insípido y sin sal.

¿Conoces más palabras raras en español? Compártelas en los comentarios.

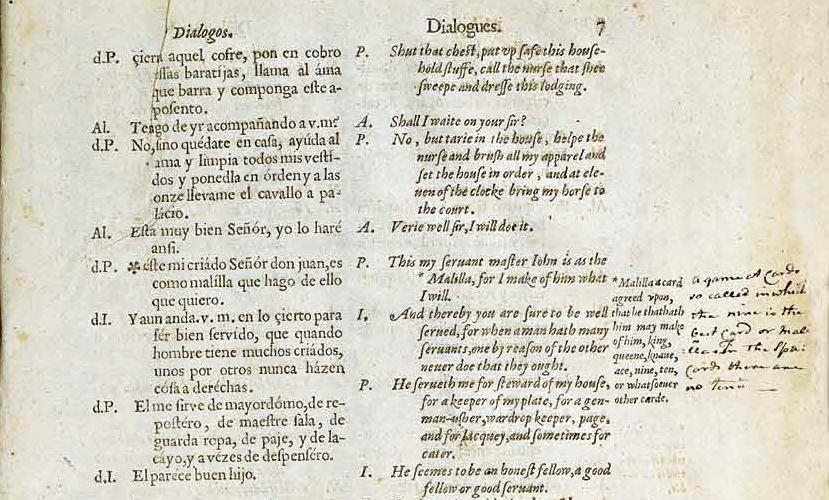

Recurso del CVC: Diálogos de John Minsheu / CVC Resource: The Dialogues of John Minsheu

Uno de los recursos interesantes en la colección de Clásicos hispánicos disponible en el CVC (Centro Virtual Cervantes):

¿Un método de español del s. XVI? … Pleasent and delightfull Dialogues, de John Minsheu (1599), forma parte de un conjunto de materiales dirigidos a facilitar el aprendizaje de la lengua castellana en la Inglaterra de los Tudor. Transcripción, facsímil y edición crítica ofrecida por el CVC. Centro Virtual Cervantes

One of the interesting resources from the Clásicos hispánicos section available at the CVC (Centro Virtual Cervantes):

A spanish teaching method from the 16th century?… Pleasent and delightfull Dialogues, by John Minsheu (1599), forms part of a collection of materiales aimed at facilitating Spanish language learning in Tudor England. Transcription, facsimile, and critical edition is offered by the CVC. Centro Virtual Cervantes.

El español es un idioma, no veintidós / Spanish is one language, not twenty-two

Muchos estudiantes de español en Estados Unidos suelen preguntar cuál es el mejor español que deben aprender, como si existiesen mejores y peores versiones del idioma. Las buenas noticias para estos estudiantes es que el español es un solo idioma, y no veintidós (el número de países donde el español es el idioma oficial).

Al igual que el inglés, el español se habla en varios países. Y, tal como ocurre con el inglés, existen variantes locales. Sin embargo, las diferencias entre estas variantes no son tan importantes como para considerarlas dialectos.

Del mismo modo quIe un estadounidense entiende perfectamente a un australiano o a un británico, pero no habla igual que ellos, un hispanohablante entiende a todos los demás. Cada país hispanohablante tiene su propia variante del idioma, pero en general estas variantes tienen más similitudes que diferencias.

Pero más a menudo de lo deseable nos encontramos con escuelas o herramientas de aprendizaje en línea que ofrecen cursos de español diferenciados bajo los nombre de “español de España” y “español de América Latina”. Incluso es fácil encontrar esta distinción en procesadores de texto muy populares que todos utilizamos rutinariamente. Pues bien, esta diferenciación es, como mucho, una media verdad.

Como es bien sabido, América Latina no es un país, sin muchos (concretamente son 19 los que hablan español), y en cada uno de ellos podemos encontrar diferencias en su habla (Argentina, México, Colombia, etc., cada uno tiene su particular variante). Lo mismo sucede con algunas variantes del inglés en Estados Unidos y eso no significa que sean diferentes dialectos o que una sea mejor que otra.

En segundo lugar, la pronunciación del español es muy consistente. Más incluso que la del inglés. ¿Sorprendidos? Lo cierto es que entre regiones hispanohablantes hay menos diferencias que entre regiones anglohablantes. Las diferencias más destacadas en pronunciación son las ya conocidas por todos: la pronunciación de la “z” y la “c” en ciertas partes de España, que en América Latina se pronuncian como una “s”.

No obstante, es justo destacar que también existen algunas diferencias más importantes. Especialmente en vocabulario. Algunas palabras tienen significados diferentes en diferentes regiones, no sólo es un tema de España y América Latina.

Otro asunto diferenciador es el uso de la conjugación del “vosotros”, que se usa en España pero no en América Latina, donde usan “ustedes”. Pero la realidad es que está diferencia se ha magnificado demasiado. La experiencia del Instituto Cervantes indica que los estudiantes no tienen ningún problema para aprender ambas formas.

En conclusión: no importa qué variante del español se estudie, ya que al final será la herramienta perfecta para comunicarse con los hispanohablantes de todo el mundo. Porque el español, como cualquier otra lengua, es esencialmente una herramienta extremadamente flexible para entendernos los unos a los otros sin importar nuestra nacionalidad o cultura.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

At some point, many students of Spanish in the US have asked the question above and wondered whether the Spanish they have heard is the “real” Spanish or just a dialect. Well, we have good news for you: Spanish is one language, not twenty two (the number of countries where Spanish is an official language).

Like English, Spanish is spoken in many different countries. And just as it happens with English, there are local variants – though the differences are not so great that they become different dialects.

If you are from the United States, you can understand an Australian or a British person, right? But you don’t speak like them. The same happens with Spanish. Each Spanish-speaking nation speaks its own variety of Spanish, but overall they have more similarities than differences.

More often than it should be, you probably have come across some language schools or online tools in the US offering differentiated Spanish courses under «Spanish (Spain)» and «Spanish (Latin America)». You can even find this differentiation in very famous word processors, for example. Well, at most, this is a half-truth.

Firstly, as you well know, the Spanish speaking Latin America is not one country but nineteen, and you can find differences between them in the same way that you can notice different English variants between states in the US.

And secondly, Spanish pronunciation is pretty consistent, much more than the pronunciation of English. That is, the differences in pronunciation, from region to region, are less for Spanish than they are for English. Surprised? The most noticeable difference regarding pronunciation in Spain as compared to Latin America is the pronunciation of the letters «z» and «c» – which in Latin America are pronounced like the letter «s» but in Spain are pronounced like «th». For the majority of students this difference is minor and of little consequence.

However, it is fair to say that there are also bigger variations, especially in vocabulary. Certain words carry different meanings in different areas. Not just Spain vs. Latin America, but region to region. The same is true regarding certain expressions; some are used in some regions, and others are used in different regions.

Another issue is the «vosotros» conjugation, which is used in Spain, but not in Latin America, where they use “ustedes”. The reality is that too much is made out of this issue. The experience at Instituto Cervantes says that students understand easily both forms.

The Bottom Line

No matter which variant of Spanish a student learns, at the end of the day it’s going to be the perfect tool to communicate with Spanish speakers all over the world. Because Spanish as any other language is just a tool, a very flexible tool, to understand each other regardless of nationality or background.