The curious look of English women travellers on Spain

Written by Marta Jiménez Miranda (University of Córdoba) (Research Group HUM-887)

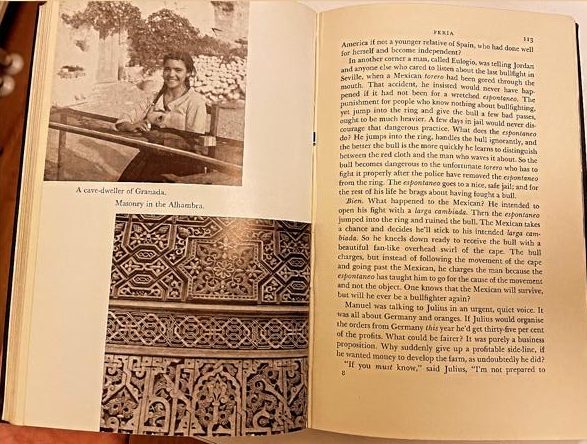

The main reason for travelling before the eighteenth century was the discovery of scientific, economic and cultural innovations in those destinations more advanced than the traveller’s own country. This phenomenon was known as the British Grand Tour (an itinerary throughout Europe, which used to include France, Germany, Switzerland, and Italy). The travels of the Grand Tour reached their highest peak in the 18th century and in the 1820s, thanks to the arrival of the railway, and the objective of these travels was far from what Spain was offering to travellers. Nonetheless, nostalgia for the bygone times caught English romantics’ attention. The aim of travelling to Spain was not only to meet their beloved past, but also to break with all those preconceived ideas that were held about Spain in the rest of Europe. In fact, the Italian writer Giuseppe Baretti mentioned it in his book A Journey from London to Genoa through England, Portugal, Spain, and France (1770), where he stated that if the Spanish “do less than the English, the Dutch or any other modern nation, it is not for any reason except that they have less to do”. Hence, it is this type of objective statements and the reforms and constructions carried out by King Carlos III of Spain that began to satisfy European travellers’ needs, encouraging them to visit Spain.

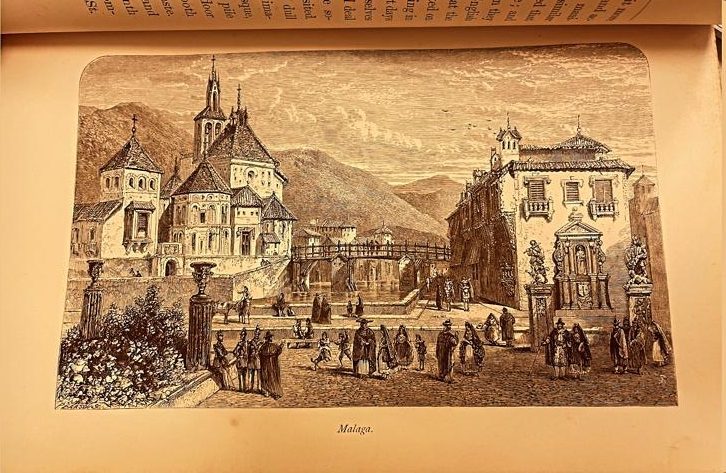

The Port of Cádiz would facilitate the connection of English travellers with Madrid. This route was also very popular among merchants and soldiers. Thus, cities such as Córdoba, Seville and Cádiz would be a good place to rest while reaching the port. Travellers felt captivated by Andalusian cities, not only because they were still stuck in the past, but they also found classical archaeology, picturesque customs, and attractive festivities.

Everything they saw contrasted with the literature they had previously read outside of Spain, and consequently they managed to break with the Spanish clichés written up until then. Therefore, we can consider we are in a turning point in Spanish travel literature, since all those texts which contained harmful criticism and inaccurate information made way to more objective texts whose intention was to make our culture known around the world.

The real Hispanophiles emerged during the first half of the 19th century thanks to fine arts. Spain was becoming an irresistible destination for romantic travellers, including Richard Ford, hispanist and drawer, who travelled to Spain with the intention of not only moving through space, but also through time.

The interest in travelling to exotic places arises due to the Romantic movement, so does the interest in Spanish dances and festivities. In addition to the foregoing, the Mediterranean climate and its famous therapeutic value encouraged many Brits to travel to Spain, more specifically to Andalusia. Well-known personalities like George Eliot and Annie J. Harvey travelled from England to Spain in order to improve their health. Annie J. Harvey said that the southern places were the best to stop the development of her chronic disease.

We did not only receive visits from travellers who looked for their treatment in our weather conditions, some other were interested in illustrious characters, as was the case of Matilda Betham-Edwards, who visited Spain in 1867 to study Velázquez, and for this reason she spent a long time in Andalusia. This same scenario happened to Marguerite Purvis, who visited Spain in 1869 attracted by the Andalusian pictorial collections.

Many experts on the matter have elaborated lists of the English travellers who visited Spain. However, there are no studies trying to make a compilation of the women British travellers who dedicated some of their trips to visit Spain. While working on these English ladies’ work, what also caught our attention was that the female view towards our country was quite different from that of male travellers. The main difference is that men tend to show an increasingly stereotyped image of our land, while women offer a much more inquisitive look, questioning clichés and misinformation about Andalusia.

Thanks to the Reina Sofía Library of the Instituto Cervantes in London it is possible to reencounter with our male and female travellers’ stories and points of view. Among the extensive collection of original books by female travellers, it is worth highlighting:

Mary Elizabeth Herbert was a translator, writer, and philanthropist. She described everything she saw in Spain in her book Impressions of Spain in 1866.

Mrs. Wm. Pitt Byrne talks about the customs, culture and infrastructure of Spain in her book Cosas de España (1866).

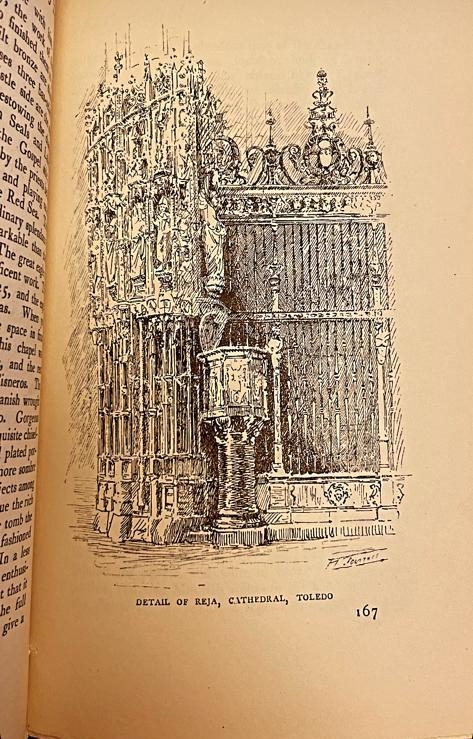

Hannah Lynch worked as a co-editor in a local newspaper when she finished school. She developed her career as a writer and died in Paris in 1904. In her book Toledo: the story of an old Spanish Capital, published a year before her death (1903), she recounts her adventures through the city of Toledo.

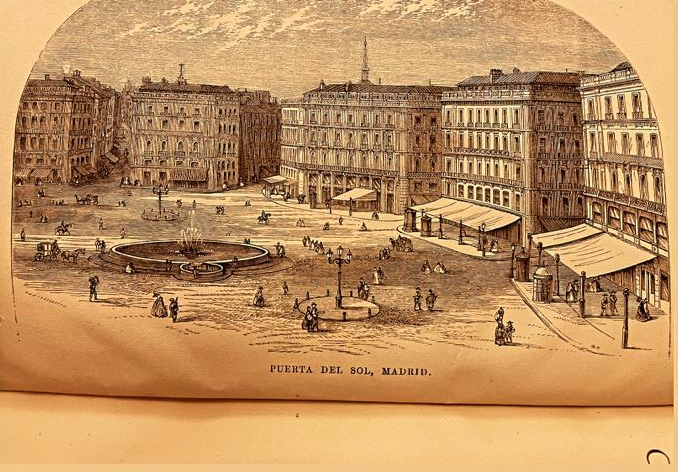

Madelaine Duke, although she used her own name to sign her works, she also signed with various male pseudonyms such as Maxim Donne and Alex Duncan. In her work Beyond the Pillars of Hercules: A Spanish Journey, published in 1957, she relates the experience of her trip to Spain, especially Andalusia and Madrid.