Luke Stegemann: “En España descubrí una Europa que me habían ocultado”

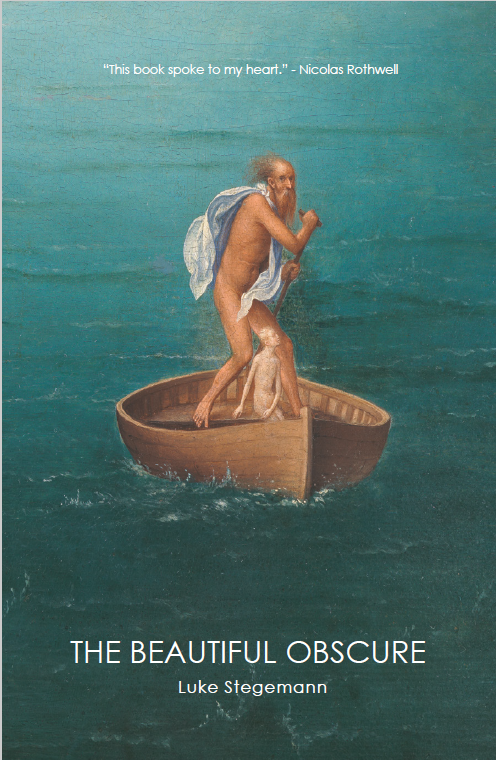

Hijo de cura anglicano y criado en el corazón rural de Nueva Gales del Sur, el australiano Luke Stegemann descubrió España por sorpresa en los años 80. Enamorado del país, no tuvo más remedio que volver a vivir en él, y desde entonces compagina temporadas en Australia y temporadas en España. Con una larga carrera como profesor, traductor y periodista -The Adelaide Review, The Melbourne Review-, y popular en las redes por su afecto a todo lo español, Stegemann ha escrito dos libros de tema completa o parcialmente español: The beautiful obscure (Transmission Press, 2017) y Amnesia road: landscape, violence and memory (NewSouth Publishing, febrero 2021).

-En The Beautiful Obscure se unen su condición de australiano que descubre España y la reflexión sobre los encuentros y lejanías entre ambos países en la Historia. ¿Qué atrae a un australiano, allá por los 80, a lo español?

Tuvo algo de fortuito. Viajaba por Europa tras terminar mi primera carrera y no había planeado pasar más de unos días. Sin embargo, una vez en España, sentí una atracción inmediata, a diferencia de lo que sentía, por ejemplo, en Grecia, Italia, Francia o Alemania. Los dos o tres días que había planificado pasar allí se convirtieron en un mes a medida que viajaba cada vez más por el país. Estamos hablando de 1984, y de una España que en muchos aspectos ha desaparecido por completo. La sensación más evidente fue la de descubrir una Europa de la que nunca me habían hablado. Era como si una sección entera del continente, cuya historia creía haber estudiado, hubiera estado oculta.

Así que la atracción era hacia lo desconocido, pero no era tan simple como la experiencia clásica de «orientalización» de «lo exótico». De inmediato quedó claro que esto era parte de mi propio patrimonio cultural, parte de la historia del continente de mis antepasados. Inmediatamente pensé: «¿Cómo no supe esto?» y luego, «¿Cómo puedo vivir aquí?» Cuando regresé a Australia y expliqué mi plan para vivir en España lo antes posible, mi familia y amigos no daban crédito. España aún no se había unido a la UE y estaba discutiendo su entrada en la OTAN. Dos años después, ya estaba en España como profesor de inglés.

Una cosa importante para mí es enfatizar que al ser australiano, a diferencia de británico o norteamericano, creo que aporto una perspectiva diferente sobre la historia y la cultura española. Vengo del «sur», del Pacífico y de una colonia europea: todo esto influye en mi manera de entender España y su lugar en el mundo. Ninguna parte de Australia fue colonizada por España (aunque podría haberlo sido), ni Australia ha tenido ningún conflicto con España. En ese sentido, no tenemos «historial», ni «equipaje» como países asociados. La gente a menudo habla de la similitud (hasta cierto punto, no debería ser exagerada) de carácter entre australianos y españoles, de gente muy amistosa y, debo decir, una reputación de tener una actitud desafiante ante la autoridad, que es principalmente una fachada y no una realidad. Ciertamente, existe la determinación en ambos países de disfrutar la vida y llenarla con el mayor placer posible, aunque los australianos son más conservadores socialmente.

-Durante siglos, la relación de España con Australia parece haber sido la historia de una frustración: ni los barcos de la aventura imperial ni los de las expediciones científicas encontrarían acomodo permanente en sus costas. A la vez, ese también parece ser el caso de Australia con España: inevitable pensar en ese verso de Ted Hughes a Sylvia Plath, en el que le dice que en su escuela nunca le hablaron de España…

En Australia, España siempre ha sido descuidada como tema de estudio. Esto se debió durante muchos años a la imitación australiana de la educación británica con todos sus prejuicios culturales y geopolíticos. En las últimas cuatro décadas nos hemos alejado de la órbita imperial británica y Australia se ha posicionado conscientemente como una potencia regional de Asia. Para ser un país «anglófono», hay un nivel muy alto de «alfabetización de Asia» en Australia. Dicho esto, salimos del paraguas británico para convertirnos en un aliado fiel y algo servil de EEUU, cuya cultura ha llegado a abrumar a la nuestra.

España es un destino turístico popular, aunque me desespera la cantidad de australianos que creen que visitar Barcelona y San Sebastián constituye «visitar España». Muy pocos aprovechan la oportunidad para explorar aquellas regiones que para mí son lo más destacado: Madrid; los pueblos de Zamora, Soria y Segovia; el Maestrazgo, las colinas de Jaén, la Tierra de Campos, sin olvidar los caminos de Toledo y Ciudad Real, a través del territorio del Quijote …

Madrid es un caso interesante en este punto. Siempre me han fascinado aquellos extranjeros a los que no les gusta. Para mí, Madrid es una concentración de tantas líneas de influencia histórica, cultural y política que es indispensable como punto de referencia. Por eso he tratado de comparar en mi libro momentos de la historia de Madrid con Australia. Ahí están los navegantes que, en época de Felipe III, reclaman atención para esa tierra, sin que les hagan caso. O cómo Carlos III muere en 1788, justo cuando los británicos fundaban lo que hoy es Sidney. Para mí, estas no son simplemente coincidencias; son líneas paralelas que fluyen a través de la historia, que no necesariamente se tocan en ningún punto, pero que de alguna manera influyen entre sí. Es por eso que sentí que las historias entrelazadas de Australia y España eran una gran historia no contada.

El poema de Ted Hughes que cita usted es un ejemplo clásico de esa interpretación de España a mediados del siglo XX desde el Atlántico Norte. Una España en blanco y negro, de clichés de la época franquista y esencialismo orientalista, que ha envejecido mucho. Esto, si me lo permiten, es la opinión de España que muchos australianos no tienen, porque no tenemos esos siglos de comparación cultural (y, a veces, de condescendencia). En The beautiful obscure no he mencionado el fútbol o las corridas de toros y muy pocas menciones al flamenco. Esto no se debe a que no aprecio y disfruto la singularidad cultural de cómo se realizan estas cosas en España, sino a que quería escribir un libro que evitara los comentarios habituales de las publicaciones.

Por cierto, y a propósito de la cuestión de la leyenda negra: al tratar de evitar los clichés anteriores, es innegable, al menos en mis lecturas culturales y políticas, apreciar un cierto tono despectivo hacia España que creo que atraviesa mucho pensamiento anglófono. Pero decirlo es invitar a la controversia. Uno puede creer que España fue maltratada por quienes la siguieron y que escribieron sus propias versiones de la historia como los «vencedores culturales», cuya influencia se extiende tanto en nuestro mundo contemporáneo. Uno puede apreciar esto y lo entiendo, sin caer en las teorías de la conspiración franquista de que un complot masónico y comunista en todo el mundo estaba tratando de destruir España. Pero he visto, con los recientes debates en torno a Roca Barea, que marcar la leyenda negra como algo real, puede etiquetarte como reaccionario, como franquista, lo cual me parece absurdo.

-¿Cómo expresar un amor por la cultura española e invitar a otros a sumergirse en ella, sin que tengan el acceso que ofrece el idioma?

A veces, la literatura y la música popular pueden ser de más difícil acceso para los extranjeros. Por esta razón, en mi libro y fuera, profundizo en el mundo del arte como un lenguaje más universal. Además de maestros obvios como Goya y Velázquez, quería que la gente conociera a algunos de mis pintores favoritos: Zurbarán, Sorolla y Zuloaga. Me cuentan mucho sobre España, y luego específicamente sobre el catolicismo, o Valencia, o Castilla. También quería expresar algunas opiniones «controvertidas»: nunca me ha gustado mucho el arte de Dalí, o de Picasso, o de Gaudí. Siempre he preferido Ribera a Velázquez. Estos son solo gustos personales. Otros favoritos son Juan de Juanes, Luis Morales, Alonso Cano, los románticos del siglo XIX y los pintores de la historia … Y quizás por encima de todos ellos, para mí, está El Greco. En verdad, el más grande.

Para mí, esta concentración en lo que es en gran medida, aunque no exclusivamente, arte religioso, es deliberada. Vivimos en una época en que la Iglesia Católica ha sufrido un enorme daño de reputación; en Australia esto es muy pronunciado. Destaco en el libro que defender el catolicismo es difícil de vender hoy en una sociedad secular y en muchos sentidos enojada. Sin embargo, existe (para alguien criado en los anglicanos como yo) una clara distinción entre la Iglesia católica como institución y el catolicismo en sí mismo, como un sistema de creencias que ha sido la fuerza motriz o la inspiración de gran parte del arte y la poesía más importantes de los últimos 500 o más años. Es este elemento del catolicismo lo que deseo celebrar; es un juicio estético, no moral.

–En España también tenemos nuestros clichés sobre Australia.

Cuando viví en España por primera vez, la ignorancia de Australia era casi total, y lo mismo era cierto en Australia con respecto a España. A finales de los años 80, el cliché de ‘Crocodile Dundee’ fue algo con lo que, como todos los australianos en el extranjero, tuve que vivir mucho tiempo. Con los años, esta situación ha cambiado drásticamente, pero Australia sigue siendo algo desconocido. Internet pone a la vista todo el mundo, pero todavía hay preguntas sobre la naturaleza de Australia: ¿Cómo de grande es realmente? ¿Hay tantos animales e insectos peligrosos? ¿Sigue siendo una colonia británica? ¿Cómo es de asiático? Creo que mucha gente está sorprendida por lo multicultural que es Australia y la gran diversidad de nuestra población.

Otro factor importante para superar la ignorancia ha ocurrido en la última década: por un lado, cada vez más jóvenes australianos hacen en España una parte esencial de sus viajes internacionales; mientras que después de la crisis financiera de 2008, miles de jóvenes españoles, sobre todo profesionales altamente calificados, encontraron oportunidades de trabajo en Australia. Esto fue una especie de «fuga de cerebros» para España, pero Australia se ha beneficiado enormemente. Los españoles a menudo se encuentran entre los principales científicos e investigadores en Australia en la actualidad.

-Australia y España afrontaron una cuestión similar: qué hacer con las poblaciones originarias.

Si, absolutamente. Pero con al menos dos diferencias: en primer lugar, en Australia este problema todavía está con nosotros, a pesar del enorme progreso que se ha logrado. De hecho, muchas personas argumentarían (y yo estaría de acuerdo) que el largo y lento proceso de reconciliación con la población indígena sigue siendo el mayor desafío de Australia como nación. En segundo lugar, en Australia, la presencia indígena no forma parte de un «imperio de ultramar», sino que forma parte del tejido cotidiano de nuestra nación. De hecho, el desarrollo de Australia, tal como lo conocemos, sólo fue posible gracias al desplazamiento de la cultura indígena.

Siempre he creído que una colonización española de Australia, sin ser ni mejor ni peor, habría tenido resultados diferentes para la población indígena. Hubiera habido más matrimonios mixtos y un esfuerzo significativamente mayor para registrar y preservar algunos de los aproximadamente 200 idiomas que existían aquí antes de la colonización, la gran mayoría de los cuales se han perdido.

–El arte, al que tantas páginas dedica en su libro, parece habernos aproximado, más allá de los estudios sobre Goya de Robert Hughes, hasta ahora “el” hispanista australiano…

Es interesante: creo que su libro sobre Goya fue uno de los mejores, mientras que su libro sobre Barcelona fue uno de los más débiles: fuera de sus áreas de especialización de arte y modernismo, en realidad no daba la sensación de haber «vivido» Barcelona. En todo caso, yo invitaría a los españoles a explorar el arte australiano, que es tan diverso como el propio país. Aunque a menudo ha seguido las tendencias europeas y norteamericanas, sin embargo, también ha traído un magnífico grupo de artistas al escenario mundial. También tiene una creciente importancia para muchos australianos, de todos los orígenes, el mundo diverso, original y profundo del arte indígena.

-Cerramos. Han sido 35 años desde que se encontró con España…

Lo digo en mi libro. Tantos años sumergiéndome en el universo español han resultado enriquecedores en más formas de las que puedo contar, pero sobre todo, hay algo más que me resulta difícil de definir, aunque que sé que es cierto. Me ha hecho una mejor persona. Esto tal vez sea cierto para todos los que aprendemos a vivir en dos culturas y dos idiomas: nos hacemos personas más sabias, más tolerantes y, espero, más compasivas. Por esto, siempre digo, y lo creo sinceramente, que estoy en deuda con los españoles.

Luke Stegemann: «In Spain I discovered a Europe I had never been told about»

Luke Stegemann was born in Brisbane and raised in Queensland, southern New South Wales and the ACT. After first visiting Spain in 1984, he later spent long periods living in Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia.

Stegemann has worked in media, publishing and higher education, and as a Spanish-English translator, in both Australia and Spain. He was formerly the managing editor of ‘The Adelaide Review’, and the founding editor of ‘The Melbourne Review’.

Stegemann has written widely on Spanish art, history, culture and politics, and now lives and works in rural south-east Queensland. He continues to spend time each year in Spain. He has recently published The Beautiful Obscure, a remarkable work which analyses aspects of Spanish cultural influence from an Australian viewpoint.

In this conversation, Stegemann talks about synergies and divergences between both countries with past, present and future perspectives, all seen within the framework of his own love of both countries.

-In The Beautiful Obscure, the discovery and the experience of Spain from your Australian background comes together with your reflection on the historical similarities, encounters and distances between both countries. The question is obvious: what attracts an Australian to Spain, back in the 80s?

In some respects it was fortuitous. Travelling around what was then ‘western’ Europe in the year after completing my first university degree, I had not planned to spend more than a few days in the north of Spain. Yet once inside the country, I felt an immediate attraction – unlike anything I felt, for example, in Greece, or Italy, France or Germany – and a planned two-three days became one month as I travelled ever deeper into the country. And this was 1984 – a Spain that has in many respects completely disappeared now. What I felt strongest – and I discuss this in some detail in the book – was a sense of discovering a Europe I had never been told about. It was as if an entire section of the continent, whose history I thought I had studied, had been hidden.

So the attraction was to the unknown, but it was not as simple as the classic ‘orientalising’ experience of ‘the exotic’. It was clear straight away that this was part of my own cultural heritage, part of the story of the continent of my ancestors. I immediately thought, “How did I not know this?” and then, “How can I live here?” When I returned to Australia and explained my plan to return to live in Spain as soon as possible – something I had never considered until then – my family and friends had no idea what I was talking about. Spain had not yet joined the EU, and was debating its entry into NATO. Two years later, and having armed myself with a second degree – this time in education – I returned to work initially as an English teacher. So began, with life in Spain in 1987, what has become the most significant chapter and influence on my adult life.

One thing that is important for me is to emphasise that being Australian – as opposed to British or North American – I believe I bring a different perspective on Spanish history and culture. I come from ‘the south’, from the Pacific and from a European colony: all of these influence my manner of understanding Spain and its place in the world. No part of Australia was ever colonised by Spain (though it might have been), nor has Australia ever had any conflicts with Spain. In that sense, we have no ‘history’, no ‘baggage’ as companion countries. People often remark on the similarity (to some extent – it shouldn’t be exaggerated) of character between Australians and Spaniards, an open friendliness and, I must say, a reputation for having a defiant attitude to authority, which is mostly façade and not a reality! Certainly there is a determination in both countries to enjoy life, and fill it with as much pleasure as possible, albeit Australians are more socially conservative.

-For centuries, Spain’s relationship with Australia seems to have been a story of frustration: despite maintaining a presence in the Pacific, neither the ships of the imperial adventure nor those of the scientific expeditions would find permanent accommodation on its coasts. Even in diplomatic and commercial terms, not a few opportunities were lost … «Your schooling had somehow neglected Spain,», said British Ted Hughes in a poem to his wife, the also poet, but American, Sylvia Plath. Has that also been the case in Australia? Are cliches the best allies of ignorance?

In Australia, Spain has always been neglected as a subject of political and historical study. Firstly, this was due for many years to Australia’s imitation of British education with all its cultural and geopolitical prejudices; latterly because, having removed ourselves from the British imperial orbit, over the past four decades Australia has consciously positioned itself as a regional Asian power. For an ‘Anglo’ country, there is a very high level of ‘Asia literacy’ in Australia. Having said that, we stepped out from under the British umbrella to become a faithful, and somewhat subservient, ally of the Americans, whose culture has come to swamp so much of our own.

Spain is a popular tourist destination, though I despair of the number of Australians who believe that visiting Barcelona and San Sebastian constitutes ‘visiting Spain’. Time pressures weigh on tourists, of course, but so few take the opportunity to explore those regions that for me are a highlight of Spain: Madrid; the villages of Zamora, Soria and Segovia; the Maestrazgo; the hills of Jaen, the Tierra de Campos, and not forgetting the backroads of Toledo and Ciudad Real, through deepest Quixote territory…

Madrid is an interesting case in point. I’ve always been fascinated by those foreigners who dislike Madrid, and express a strong preference for Barcelona, or even Valencia or San Sebastian. For me, Madrid is such a concentration of so many historical, cultural and political lines of influence, it is indispensable as a reference point. This is why I have looked to compare moments from the history of Madrid with Australia: two examples are those navigators, returned from the Pacific, spending years begging at the court of Phillip III for funds to return to discover what they sense is still there, and never quite making it… or Carlos III and the building of the Puerta de Alcalá: it arose in the very same years as the British were planning their penal colony at the bottom of the world, and of course the death of Carlos III in 1788, the same year the British founded Port Jackson, now Sydney.

For me these are not simply coincidences; they are parallel lines that flow through history, not necessarily touching at any point, but somehow bearing an influence on each other. This is why I felt the interweaving histories of Australia and Spain was a great, untold story.

But it is also interesting to consider the Ted Hughes poem you quote. For me it is a classic example of that mid-century north-Atlantic interpretation of Spain. A black and white Spain of Franco-era clichés and orientalist essentialising, that has aged badly. This, if you’ll permit me, is the view of Spain many Australians do not have, for we do not have those centuries of cultural comparison (and at times, of condescension). You’ll have noticed that in a 435 page book about Spain, I have made no mention of football, or bullfighting, very little mention of ‘blood and death’, and only very few mentions of flamenco. This is not because I do not appreciate and enjoy the cultural uniqueness of how these things are performed in Spain (in particular, the cante jondo tradition of flamenco) but I wanted to write a book that avoided all the usual staging posts for commentary on Spain.

(Incidentally, the question of the leyenda negra: while trying to avoid the above clichés, it is undeniable, at least in my cultural and political readings, of a certain dismissive tone towards Spain that I think runs through a lot of Anglo thinking. But to say so is to invite controversy. One can believe that Spain has been poorly treated by those who came after her, and who wrote their own versions of history as the ‘cultural victors’ whose influence extends so much into our contemporary world; you can see this, and understand it, without falling into Franco-like conspiracy theories, that a worldwide masonic and communist plot was out to destroy Spain. But I’ve seen, with the recent debates around Roca Barea, that to flag up the leyenda negra as something real, can get you tagged as reactionary, as Francoist…!)

One other obvious question in writing this book: how to express a love for Spanish culture, and invite others to immerse themselves in it, without them having the access afforded by the language? (Because no matter how much we can translate, ‘love’ and ‘amor’ are not the same thing; ‘evening’ and ‘atardecer’ are not the same… they all carry the weight of their own cultural heritage, and to say one thing, is not the same as to say the other! I have recently been doing some short translations of the poetry of Miguel Hernández into English, and it is enormously difficult to convey the sense of his words… the meaning, maybe, but the sense, the feeling… almost impossible!!) This is why I have made little mention of two of the greatest aspects of Spanish culture – its literature and its popular music – as they are difficult to access properly for foreigners. For this reason, I go in depth into the world of art, as a more universal language. Apart from the obvious masters Goya and Velázquez, I wanted people to know some of my favourite painters: Zurburán, Sorolla and Zuloaga. They tell me so much about Spain, and then specifically about Catholicism, or Valencia, or Castile. I also wanted to float a few ‘controversial’ opinions: I have never really liked the art of Dalí, or much of Picasso, or Gaudí. I have always preferred Ribera to Velázquez. These are just personal tastes. Other Spanish favourites are Juan de Juanes, Pedro Orrente, Luis Morales, Alonso Cano, the nineteenth century romantics and history painters… And perhaps above them all, for me, is El Greco. Truly, the greatest.

(And how often would I visit the Prado and find a room full of people crowding around Hieronymus Bosch – which is normal – but completely ignoring that singular masterpiece, on the opposite wall, which is Patinir’s vision of Charon crossing the Styx!)

For me this concentration on what is largely, though not exclusively, religious art, is deliberate. We live in a time where the Catholic Church has suffered enormous reputational damage; in Australia this is very pronounced. I make the point in the book that to defend Catholicism is a hard sell nowadays in a secular and in many ways angry society. However there is (for someone raised Anglican like myself) a clear distinction between the Catholic Church as an institution, and Catholicism itself as a belief system which has been the driving force, or inspiration, for much of the greatest art and poetry of the last 500 or more years. It is this element of Catholicism I wish to celebrate; it is an aesthetic judgment, not a moral one.

– It is true that the first city in the world to dedicate a street to AC / DC was Spanish … but the lack of knowledge between the two countries seems to have been a shared passion: in Spain we also have our cliches about Australia.

When I first lived in Spain the ignorance of Australia was almost total – and the same was true in Australia as regards Spain. I confess in the book how, as a young boy, I thought Seville was an Italian city… In the late 80s, when I was living in Madrid, the cliché of ‘Crocodile Dundee’ took over – something which all Australians abroad had to live with for far too long! Over the years, this situation has changed dramatically, but Australia remains something of an unknown. The internet brings the whole world into view, but there are still questions about the nature of Australia: just how big is it really? Are there so many dangerous animals and insects? Is it still a British colony? How Asian is it? I think a lot of people are surprised by just how multicultural Australia is; the huge diversity of our population.

Another significant factor in overcoming this ignorance has occurred over the past decade: on the one hand, more and more young Australians make Spain an essential part of their international travels; while after the 2008 financial crisis, thousands of young Spaniards – above all highly skilled professionals – found work opportunities in Australia. This was something of a ‘brain drain’ for Spain, but Australia has benefitted enormously. Spaniards can often be found among the leading scientists and researchers in Australia today. Additionally, there are community networks of young Spanish people that simply did not exist 25 years ago.

-Australia and Spain, even at different times, faced a similar question: what to do with the native populations, already in Australia, already in Spanish America …

Yes, absolutely. But with at least two differences: firstly, in Australia this problem is still with us, despite the huge progress that has been made. In fact, many people would argue (and I would tend to agree) that the long, slow process of reconciliation with the Indigenous population remains Australia’s greatest challenge as a nation. Secondly, in Australia the Indigenous presence is not part of an ‘overseas empire’ but forms part of the daily fabric of our nation. In fact, the development of Australia, as we know it, was only made possible by the displacement of the Indigenous culture, with not just the major loss of life but also the profound cultural loss of languages and knowledge of the land and its uses.

While historical ‘what might have beens’ are of little practical use, I have always believed a Spanish colonisation of Australia, without being either better or worse, would have had different outcomes for the Indigenous population. There would have been significantly greater intermarriage, and a significantly greater effort made to record and preserve some of the approximately 200 languages that existed here prior to colonisation, the great majority of which have been lost. And of course, Spain would have colonised Australia around two centuries before the British, so European Australia would now be a country of some 400+ years, like the US, rather than around 230 years.

-The link or bilateral knowledge is surely more intense after the Civil War, in which there were Australians of both sexes. But also the art, to which you dedicate so many pages in his book, seems to have brought us closer, beyond Ted Hughes’ studies on Goya, until now “the” Australian Hispanicist…

Firstly a small correction – I think you mean Robert Hughes in this case! It is interesting – I think his book on Goya was one of his finest, while I thought his book on Barcelona was one of his weakest (partly because it was really a book about Catalan modernism, which is fine, but Barcelona is much more than that; I thought it was obvious that outside of his specialist areas of art and modernism, he didn’t really give a sense of having ‘lived’ Barcelona. In fact, it felt very much as though research assistants had done most of the work. I couldn’t smell Barcelona, or hear her breathing in this book…)

Perhaps what I’ve said in the above paragraphs about art is sufficient. I would invite Spaniards, however, to explore Australian art, which is as diverse as the country itself. While Australian art has often followed European and North American trends, it has nevertheless brought a magnificent stable of artists onto the world stage. And also, of increasing importance to many Australians, of all backgrounds, is the diverse, original and profound world of Indigenous art. It represents, as much as anything, the triumph of the survival of our Indigenous peoples, and allows the non-Indigenous person a glimpse into their representations of ceremony, law, and the origins and nature of the world.

A final comment: I’ve said this in the book, and say it also whenever I talk about the book. Having spent 35+ years immersing myself into the Spanish universe has been enriching in more ways than I can recount, but above all, there is something else that I find hard to define, but which I know is true. It has made me a better person. This is perhaps true of all of us who learn to live across two cultures and two languages: we find ourselves wiser, more tolerant and, I hope, more compassionate persons. For this, I always say, and sincerely believe, that I am in debt to the Spanish people.