Getting to Know Ibero-American Classical Music: 5 Pieces to Start You Off

Pianist, Latin Classical music expert and Artistic Director of the Iberian & Latin American Music Society (ILAMS), Helen Glaisher-Hernández, recommends five pieces of Ibero-American classical music to our readers by way of introduction to this exuberant repertoire.

«I would highlight the following pieces of 20th-century repertoire which, for me, stand out for their ingenuity and originality,» says Glaisher-Hernández. The following list includes works that «conjure up imaginary musical landscapes, capable of opening doors into different, new dimensions through their ability to articulate otherworldly sounds and textures. It’s through pieces like these that we can observe Spanish and Latin American composers making genuinely original contributions to classical music that go beyond the mere ‘echoing’ of conventional European trends, as the Cuban writer, Roberto Retamar, famously put it,» adds Artistic Director of ILAMS.

- Xochipilli: An Imagined Aztec Music (1940)

Carlos Chávez (Mexico)

Carlos Chávez was known as one of the ‘Big Three’ Latin American composers of the early-to-mid 20th century, along with the Brazilian composer, Heitor Villa-Lobos, and the Argentine composer, Alberto Ginastera. The enormity of Chávez’ musical imagination and his revolutionary achievements influenced many subsequent generations of composers and changed the course of classical music-making throughout the Americas and beyond.

A child of the Mexican Revolution, Chávez became a leading feature of the so-called ‘Mexican Renaissance’ – a flowering of socialist writing, mural painting and architecture that took place in the wake of the Revolution – alongside other intellectuals and artistic figures such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. A central focus of this movement was a desire to bring the masses into the fold of the arts, in part by celebrating the indigenous oppressed, and Chávez’ music is replete with references to native Mexican music and culture.

In this vein, Chávez is best known for his Symphony No. 2 ‘Sinfonía india’, but for me it is the much more radical Xochipilli which most vividly invokes the Mexican Indian, in the form of the eponymous Aztec god of flowers, music and dance. Composed in 1940 for winds and percussion, the work was commissioned by Rockefeller for a MoMA exhibition in New York titled Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art. Chávez designed the piece so as to didactically showcase the Aztec instruments he was actively researching, but in doing so he also produced a radical and compelling piece of art, and a tour de force for any percussion section, requiring all sorts of weird and wonderful indigenous Mexican instruments. I programmed this piece at the Southbank Centre in 2012 as part of a ‘Revolutionary Concert’ celebrating the collective Latin American bicentenaries of independence, and I remember spending an inordinate amount of time trying to track down ‘hawksbells’, amongst other things.

Anyone listening to this piece who has ever visited Mexico’s pyramids and archaeological sites (and even those who haven’t) will find themselves plunged into the pre-Hispanic world in a very compelling way. A work of tremendous power, to hear it performed live feels like coming face to face with the might of the entire Aztec empire – especially as the piece gradually moves towards the formidable climax of its final movement. Chávez appears to achieve the impossible: to transport us back in time to pre-Columbian Mexico and resurrect the Aztec himself. If you can’t hear this music in concert, make sure you have the volume on your stereo speakers at home cranked up to the maximum!

A wonderfully off-the-wall, funky and fun piece, Xochipilli belies so much of Chavez’ other characteristically astringent music, which is well-known for being difficult to listen to. In contrast, I celebrate this work as an example of how, for those with less adventurous tastes at least, atonal and polytonal music can be just as beautiful and exciting as any other.

For listening, I recommend the version by Mexico’s Tambuco Percussion Ensemble performing with La Camerata on the 1994 album, ‘Carlos Chávez’.

2. Motet em ré menor ‘Beba Coca-Cola’ (1967)

Gilberto Mendes (Brazil)

This is another piece I programmed for my ‘Revolutionary Concert’ at the Southbank Centre in 2012. Out of a later period of left-wing politics, from 60s Brazil, emerged a work that speaks to Latin American anxieties over the rising dominance of American economic imperialism, offering a caustic musical indictment of the ‘contamination’ of Brazilian society by the unchecked importation of American cultural values. The Motet in D Minor, also known by the sobriquet ‘Beba Coca-Cola’ (‘Drink Coca-Cola’), is a work for mixed choir by the Brazilian composer Gilberto Mendes, based on the homonymous 1958 text by the Brazilian poet Décio Pignatari. And it is, in my opinion, nothing less than a Postmodern masterpiece.

Writing in the verbivocovisual ‘Concrete Poetry’ tradition, Pignatari plays on the marketing jingle of the multinational soft drinks company – Coca-Cola being one of the most recognisable symbols of capitalism worldwide, and advertising being part of capitalism’s essential, nefarious machinery – in order to attack the ‘system’ from within in true Postmodern fashion (instead of from the outside). The slogan-subject, ‘Beba Coca-Cola’, is turned in on itself in an act of metaphorical autosarcophagy that evokes Karl Marx’s assertion that ‘capitalism tends to destroy its [own] two sources of wealth: nature and human beings’. In both the poem and the musical work, the syllables of this sound bite are perpetually scrambled and re-scrambled in a musical gesture of anti-propaganda, the words ingeniously twisted in all directions to proffer various sorts of mischievous and derogatory semantics. ‘Babe cola’, for example (in Portuguese) alludes to the ‘drooling’ of coke, whilst ‘caco’ implies the imbibing of broken glass.

This babble provides an inexorable ostinato chant throughout the piece; a parody of the relentless subliminal message of the sales pitch. (It reminds me, more specifically, of a more recent Christmastime UK Coca-Cola ad – you know: the one where they sing ‘Holidays are coming… Holidays are coming…’). In counterpoint with this ‘mantra’, the composer scores a succession of onomatopoeic tricks, employing extended techniques such as spoken vocal lines, glissandos and breathy effects to mimic sounds such as the opening of the bottle and the escaping gas, the intoxicating effect of the bubbles. Use of microtonality incites a feeling of nausea, whilst menacing, almost gothic, dissonant intervals threaten the approach of very real malady. Eventually this bilious prattle finds relief in the form of a glorious belch by a male soloist. (I should add that this is by no means easy to pull off in the context of a live performance, as I found out with my own singers. I would strongly recommend that any choral directors attempting this piece have a burp machine on standby!)

The piece resumes only to descend into anxious cacophony, as the chant builds into an aggressive protest. If by now the listener hasn’t already got the message, the ending punch line makes the moral of the piece crystal clear, with a final re-fashioning of the slogan into a new, unequivocal word: ‘cloaca’ (‘sewer’, or ‘cesspool’). The deconstruction of the jingle is thus complete; capitalism is exposed as poisonous filth. Through ample use of the delights of the Postmodern toolkit (satire, sarcasm, repetition, intertextuality and self-consciousness), Mendes achieves a persuasive repudiation of the act of unbridled consumption itself.

The response of Coca-Cola to the premiering of this piece provides a perfect coda to the story of its composition. In lieu of the reprisals Mendes had anticipated, Coca-Cola instead sent one of their representatives to deliver a box of soft drinks to him in person, by way of thanks for ‘advertising’ the brand. ‘Speak good or bad, but talk about me,’ was the representative’s rationale. It brings to mind an aphorism often attributed to Lenin: ‘The last capitalist we hang shall be the one who sold us the rope.’

As far as I’m aware, there are no commercial recordings of this piece, or at least none that are readily available. Don’t ask me why, although given the work’s politics this seems somehow appropriate. Luckily, however, there is a nicely-filmed video clip on Youtube, featuring a performance by the OSESP Choir, excerpted from the documentary, ‘A odisseia musical de Gilberto Mendes’. What’s also nice is that you get to see a shot of the composer at the end.

3. String Quartet No. 2 ‘Reflejos de la noche’ (1984)

Mario Lavista (Mexico)

I first encountered this piece at a concert of Latin American music I attended at St John’s Smith Square many years ago featuring the Brodsky Quartet. It remains etched in my memory as one of the most incredible concerts I’ve ever attended, and the highlight was undoubtedly this piece.

Reflejos de la noche (Reflections of the Night), like Mendes’ Motet in D Minor, is another ‘festival’ of extended techniques and special timbric effects by contemporary Mexican composer, Mario Lavista. The composer’s assertion that ‘few instrumental genres have awoken the most intimate and refined imagination from composers as the string quartet’ is attested by the fact that this remains one of his most frequently performed works. In fact, following on from a long tradition of string quartet writing in Mexico, Lavista went on to write six string quartets in total, the majority of which were inspired by his acquaintance with the ensemble now widely-considered Mexico’s leading string quartet, the Cuarteto Latinoamericano.

In the score, Lavista offers some orientation in the form of a 1926 poem by the Mexican poet, Xavier Villarrutia, called Eco:

La noche juega con sus ruidos / The night plays with the noises

copiándose en sus espejos / copying them in its mirrors

de sonidos / of sounds

The work as a whole conveys a random, improvisatory feel that draws on the composer’s strong aleatory background. It is held together by a perpetual spring of gently imbricated harmonics, the ‘reflejos’ of the piece, which aimlessly float around the air like mosquitoes on a humid night. In Lavista’s own words, ‘using harmonics is, in some way, to work with reflected sounds; each one of them is produced, or generated by a fundamental sound that we never get to hear; we only perceive its harmonics, its sound-reflection.’ This gives the music an ethereal atmosphere not dissimilar to the whimsical, high-pitched interludes in the second movement of Ravel’s String Quartet in F Major. (After hearing Lavista’s piece, it may not surprise you to know that Lavista also wrote a work for oboe and eight wine-glasses!)

Other subtle textures are layered over each other – glissandi, trills and ricochet bowing help to bring all sorts of images to mind; the night sky, complete with the darting of shooting stars. The Mexicanist in me also hears the nocturnal hum of chirping crickets, and coyotes howling distantly in the background.

The repetitious and amorphous nature of the work leaves very little room for extended commentary, but that’s not to detract from its beauty; on the contrary, the work’s strength lies in the mesmeric sense of stasis that Lavista is able to sustain throughout the piece. …And so in the end, the piece doesn’t really, well…end; it just slowly and gently evaporates into the night…

The definitive version of this piece to listen to, historically speaking, is naturally the 2001 world premiere recording by the Cuarteto Latinoamericano, ‘Latin American String Quartets’ (but for sentimental reasons I also like to listen to the Brodsky’s version on their album, ‘Rhythm and Texture’).

4. Paisajes: ‘El lago’ (1947)

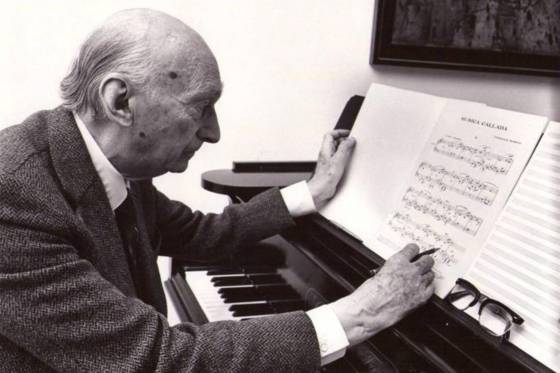

Frederic Mompou (Spain)

In some ways this piece is not very far removed from the contemporary Impressionism of Mario Lavista’s Reflejos de la noche, but if tonality is more your thing, you can’t fail to love this sublime miniature, ‘El lago’, by the Catalan composer, Frederic Mompou. I first encountered the music of Mompou when I was studying at Trinity College of Music in London with Elena Riu – a leading exponent of his music with whom I worked on several of his pieces.

I should start with the caveat that any pretensions to crystallise Mompou’s art in words are, in a sense, self-invalidating, since Mompou’s music is ultimately an expression of the ineffable and the esoteric; the privileging of the poetic over the prosaic. Or, as Schwerké more eloquently put it, ‘there is no exegetical system or method of chemical analysis nice enough to discover his secret.’

Mompou was really a magician in the guise of a composer; music his unique brand of transcendental magic. His first-ever composition, Cants magics (Magic Spells) is oneI’ve delighted in performing many times. But his interest in subjects such as magic, witchcraft, and even shamanism, are indicative of a more profound concern with spirituality more broadly. Mompou’s approach to composition was heavily informed by the mysticism of the Spanish Golden Age, the writings of St John of the Cross prompting pieces such as Cantar del alma and his Música callada (Silent Music), the work which best encapsulates his musical philosophy and which has been described as his magnum opus.

…That is, if ‘magnum’ is indeed a word we can apply to this music; Mompou prefers the small in scale, the intimate performance space, and the sparsely-notated score. He weaved a personal style of minimalism that allowed him to achieve maximum expression within the minimum possible means, and revelled in subtracting as many ‘unnecessary’ notes from the final work as possible. ‘I don’t compose music; I de-compose it’, he once said. These qualities, paired with a longing to rediscover the lost sensibilities of childhood, its joy and naivety, convey a kind of primitivism that led Wilfrid Mellers to describe Mompou’s music as a return to Paradise after the Fall. Whilst Stephen Hough refutes the notion that Mompou deserves a place in the hall of the ‘great’ composers, I would venture that he is, in fact, perhaps the greatest of all composers, for, free from the vanities of self-awareness, such as pretense and affectation, his music seems to touch the very forces of Creation itself.

Mompou stands apart from all his Spanish (and indeed non-Spanish) musical contemporaries; the ultimate iconoclast. ‘Quite simply put, Mompou is Mompou – there is no other music quite like his,’ say Rawlins/Hernández-Banuchi. An infamous introvert, he eschewed all ‘isms’, fads and fashions in favour of finding an independent, uncompromisingly personal voice and language. As such, he succeeded where most 20th-century composers failed: to discover an entirely fresh, tonal currency of exquisite and provocative harmonies without ever lapsing into even the slightest suggestion of kitsch or sentimentality. With the art of an alchemist, he turned dissonance into euphony.

There are traces of French influences (Mompou lived and studied in France for 30 years), but Mompou is certainly no mere ‘Spanish Debussy’ or ‘Spanish Satie’ – although his music is profoundly Spanish. There are brief, ubiquitous echoes of Catalan folk tunes, and a proliferation of the bright, metallic sonorities of local church bells. (It is no coincidence that Mompou’s grandfather owned a bell-foundry). But more fundamentally, there is a kind of dark side to his music that only Spanish artists are capable of.

‘El lago’ (‘Lake’) from Paisajes (Landscapes)is my absolute favourite of Mompou’s works. More than an archetypally pastoral image that the piece’s title might suggest, or the cascading fountains of Barcelona’s Montjuic Park that inspired it, the piece really reminds me, in a very personal way, of my experience of standing before the natural subterranean pool at the otherworldly concatenation of volcanic caves in Lanzarote known as Los Jameos del Agua. The eerie stillness of the cavern is evoked in repeated, undulating pianissimo chords, lending a hypnotic timelessness to the opening section of the piece that lulls you into a (false) sense of forgetful oblivion.

This is interrupted by the micro-dramas of a more disturbing middle section where Mompou reveals his fiery Spanish side with waves of cascading arpeggios. Mompou’s understanding of the piano’s resources allow him to showcase the sparkle of the instrument’s top register, contrasted sharply with its deep, resonating bass. Interspersed are dramatic shimmery tremolo passages that recall the swarming apian trills of Falla’s ‘Danza ritual del fuego’ (‘Ritual Fire Dance’), which are followed by slow, deep, pondering monophonic passages that provide added layers of enigma and obscurity. What’s satisfying is hearing the pauses between the phrases; contemplating the beauty of the decaying sound, reverberating as if in an echo chamber.

In the final section, disquiet gives way to tranquillity as the piece reprises its original idea. This is typical of Mompou: tension, if not resolved, is, at least, gently dissipated. All emotions – both positive and negative – are embraced and co-exist on equal terms, expressed spontaneously, moment-to-moment, rather than as part of a grand scheme, so that any sense of angst is fleeting and soon forgotten. Part of Mompou’s genius lies in this ability to conjure up several conflicting emotions, not only within the same piece, but at the same time – an impressive feat made all the more awesome given the brutal economy of his means. Perhaps that’s why the atmosphere of this piece is so difficult to put your finger on: the slow sections are melancholic in a detached, accepting kind of way, like the vague memory of a trauma long overcome. But paradoxically, there is also contentment, mystery and even danger, alongside other sensations more difficult to grasp. Both disturbing and reassuring at once, the music would seem to provide an emollient antidote to its own discomfort, thus offering a ‘therapeutic’ kind of listening experience in which pain is transcended through its own validation. Indeed, I highly recommend listening to Mompou if you are feeling in need of some emotional healing. It’s like balm to the soul.

The bad news is that although there are many available recordings of this piece, most are, quite frankly, massacres of Mompou’s music. Ironically, despite (and perhaps because of) the apparent simplicity of Mompou’s writing, his music demands a pianist of an equal capacity for nuance and understatement as its author, and ‘El lago’ especially is a piece to really sort the wheat from the chaff. Stephen Hough puts it slightly differently: ‘There is nowhere for the sophisticate to hide with Mompou. We are in a glasshouse, and the resulting transparency is unnerving, for it creates a reflection in which our face and soul can be seen.’

The good news is that amongst the wheat we can count on the sublime Arcadi Volodos, whose version on the album, ‘Volodos Plays Mompou,’ remains, for me, unmatched, and untouchable. I would even go far as to say that it surpasses the composer’s own recorded performances. Volodos is able to really maximise the music’s possibilities and make it speak. His extraordinary ability to sound-paint yields levels of pianissimo you never knew existed. Crucially, he also has an intelligent grasp of timing and an audacious and dynamic talent for rubato, always sensitive to the unfolding writing, and with an expansiveness in all the right places that heightens the music’s mystique.

Mompou was also a celebrated concert pianist before he started composing, and there is a vintage recording of him performing his entire piano catalogue that is also worth checking out: ‘Mompou: Complete Piano Works’. My only reservation with this album in the strange reverb in the production – I can’t decide if it adds to the effect of the music, or just makes it sound distorted.

5. Tango Suite (1984)

Astor Piazzolla (Argentina)

Last, but by no means least, I could hardly miss out Astor Piazzolla – not only because, in our time, this Latin American composer has now overtaken all others as the most famous and most popular internationally – but also because Piazzolla is where my passion for Latin Classical truly began.

Growing up learning the piano, I was naturally familiar with famous names like Falla, Albéniz and Villa-Lobos, as canonised by the ABRSM. A musicologist in the Canary Islands also introduced me to the vibrant piano music of Ernesto Lecuona, who remains one of my favourite composers. But it wasn’t until my year abroad in Buenos Aires that I began to realise the enormity of this ‘Latin Classical’ phenomenon, and it was Piazzolla who opened the door. I went to a lot of concerts with friends from my year group at the conservatoire, and Piazzolla seemed to be everywhere. One event that sticks in my memory is an anniversary concert we attended at the Teatro Colón (that year, 2002, marking ten years since the composer’s death). After that, I was completely hooked.

I think the Tango Suite for two guitars is probably the first piece by Piazzolla that I listened to. It’s worth noting that Piazzolla’s music covers the whole spectrum of music from the extremes of classical to popular, and everything in between (which often makes it difficult to categorise). Ironically, in classical circles Piazzolla is often better known for his more popular output, his classical works being performed only very rarely. These are what Allison Brewster Franzetti has characterised collectively as ‘the unknown Piazzolla’. This is a shame because this is where some of Piazzolla’s most interesting music is to be found. If you’d like to explore Piazzolla’s more classical side, the Tango Suite is a great place to start.

The Tango Suite was commissioned by the formidable Brazilian classical guitar duo, the Assad Brothers, who premiered it in Paris in 1984. The work broke new ground within the guitar duo repertoire, employing a dazzling array of resources, including numerous extended techniques and percussive effects.

Written in three movements, the work opens with echoes of Piazzolla’s evergreen Histoire du tango, but soon reveals itself as a relatively more complex, mature and ‘contemporary’ piece – that is, without ever descending into pure academicism. Indeed, one of the delights of this work for me is the way in which Piazzolla seems able to seamlessly syncretise popular material with more experimental methods; his talent for naturalistically reconciling the topical with the abstract. Even in Piazzolla’s more classical works, however, the tango is never far away (albeit more, or less, sublimated) and in this piece we can also hear tango rubbing shoulders with some of Piazzolla’s other major influences: jazz, Bach, Ginastera and even Stravinsky. The result is an ‘urban’ species of ‘classical cool’ which simultaneously challenges its performers to demonstrate their grasp of the ‘swing’ of the tango whilst also having to negotiate the exacting demands of the most difficult of classical guitar techniques. I think this urban cosmopolitanism is one of the reasons why Piazzolla has found particular favour today amongst slighter younger audiences.

The slower, second movement is very lyrical, conveying the more languid, sultry side of the tango, and this offers some brief respite before the piece launches into the exhilarating, relentless drive of the final movement. Here, Piazzolla lets his imagination really run wild, lurching capriciously between ideas, moving restlessly between unexpected harmonies. A (slightly) more contemplative middle section cedes to the finale: an unstoppable rollercoaster ride of further adventures through precarious harmonic and rhythmic turns. This final movement in particular interweaves a pleasing dichotomy of melody and rhythm that is particular only to Piazzolla.

There aren’t many recordings of ‘Tango Suite’ out there – I suspect for the same reason that there are so few live peformances – because, technically speaking, it’s at the harder end of the guitar repertoire. The best version I’ve come across to date is the 1998 recording by Argentine guitarists Walter Ujaldón and Marcela Sfriso. Ujaldón was on the guitar staff at the Conservatorio Nacional Superior when I was there in 2002 and I had the pleasure of hearing him perform it with Sfriso in concert. Unfortunately, their album, titled ‘Solos y duos: Piazzolla, Britten, Bach, Ginastera, Kleynjans’, has long been deleted and is difficult to get hold of these days, but I have seen second-hand copies advertised for sale on the internet, so it’s worth doing a search.

In addition, the key version to listen to is the world-premiere recording, ‘Latin American Music for Two Guitars,’ by the Assad Brothers, for whom the piece was written. The Assads are undoubtedly brilliant in everything they do, but for me this interpretation lacks the more authentic, slower tempo and Argentinian rubato of Ujaldón/Sfriso in favour of a more typically frenetic Brazilian attack. In this, the piece loses some of the sensuality and pathos that lends it greater ‘tangitude’ and local meaning.