«I think what we all miss most is the very heart of what we do: trying to communicate something essential, and sharing a precious connection with an audience»

We interview tenor Nicholas Mulroy ahead of his concert Cubaroque, as part of Baroque at the Edge 2021, that invites leading musicians from all genres to take the music of the Baroque and see where it leads them.

Baroque at the Edge is not able to invite audiences to LSO St Luke’s for the 2021 festival. Instead all events will be available to buy online from now until the January release date, and subsequently available to view until 31 March 2021.

Mulroy was born in Liverpool, and has had a busy and varied career as a singer, where personal highlights have included Bach’s Matthew Passion in his own Thomaskirche, Monteverdi Vespers in Carnegie Hall, and two visits to the fantastic Australian Chamber Orchestra, as well as a broad discography including Handel, Purcell, and Piazzolla’s amazing María de Buenos Aires.

Mulroy combines singing with teaching at Goldsmiths, Cambridge, and the Royal Academy of Music, and directing. He has recently been named Associate Director of Scotland’s Dunedin Consort.

How did you become interested in becoming a tenor?

I sang as a child in Liverpool, and since then have always been involved somehow with music, whether singing or instrumental – when my voice changed I played in local youth orchestras, and had great fun in jazz and rock groups. I also sang salsa and played serenatas during my time in Ecuador, which was a lovely way of getting to know different kinds of music and performance style!

You regularly appear with leading ensembles throughout Europe, which ones do you remember as the most special ones?

I’ve had immense fortune to work with many amazing colleagues, whose inspiration and talent of course I miss at the moment. Every musician, and therefore every ensemble, has their own special energy and qualities, so it’s impossible to highlight some over others. I do, however, have fond memories of favourite concert halls: the Palau in Barcelona with its inimitable architecture; the Chagall ceiling in the Paris Opera; outdoor concerts in the Palacio Carlos V in the Alhambra. We are so fortunate as musicians to be able to work in these spaces, where the fleeting beauty of music can interact, often unforgettably, with architectural wonders.

2020 has been a difficult year to culture with the cancellation of many events and concerts, how has the covid pandemic impact your career?

I think it’s fair to say that we’re all brought low by this pandemic, and not always supported either by governments, though some artistic institutions have been superhuman. There have of course been positives: the chance to refine and reflect, and the emphasis on inner geography is a positive side-effect when it comes to thinking about creativity. On the other hand, apart from the practical implications of having concerts deleted, and income decimated, I think what we all miss most is the very heart of what we do: trying to communicate something essential, and sharing a precious connection with an audience. The fact that so little is feasible at the moment diminishes both musician and listener.

Cubaroque takes place next week. You take a new brand-new exploration from three of this country’s most distinguished baroque musicians. What does it mean to you?

The music of the Baroque has been the central element of my career until now, so singing this repertoire – Monteverdi, Purcell, Marín – is always a little like a homecoming. It’s repertoire of such expression and beauty, and its durability is testament, I think, to the way it still has huge appeal and value now. It’s a challenge and a privilege to try to make the music of the past mean something for people today.

You investigate the cultural and political background of the 1960s Latin-American and Spanish song-writing giants. How do you approach them in Cubaroque?

We wanted to shine some light on these wonderful musicians, and respond to the domination of English-speaking pop music in today’s cultural landscape. Silvio Rodríguez and Víctor Jara are figures of gigantic significance but not well-known outside the Spanish-speaking world. Both carry importance both politically and artistically in a way that is rare anywhere, and shared by only very few: one thinks of Bob Dylan or John Lennon perhaps. The way their creativity interacts with political power is something they share with Purcell and Monteverdi, both of whom were based at institutions of far-reaching influence. In one sense, we’re limited by our instrumental possibilities, so we only play acoustically, and with one voice and two guitars (or similar instruments). We have found, however, that – in spite of the historical and geographical separation – all this music shares many things: sometimes a harmonic progression or a melodic echo, often a similar feeling of confessional intimacy, and always direct, truthful responses to the possibilities that these texts and stories offer.

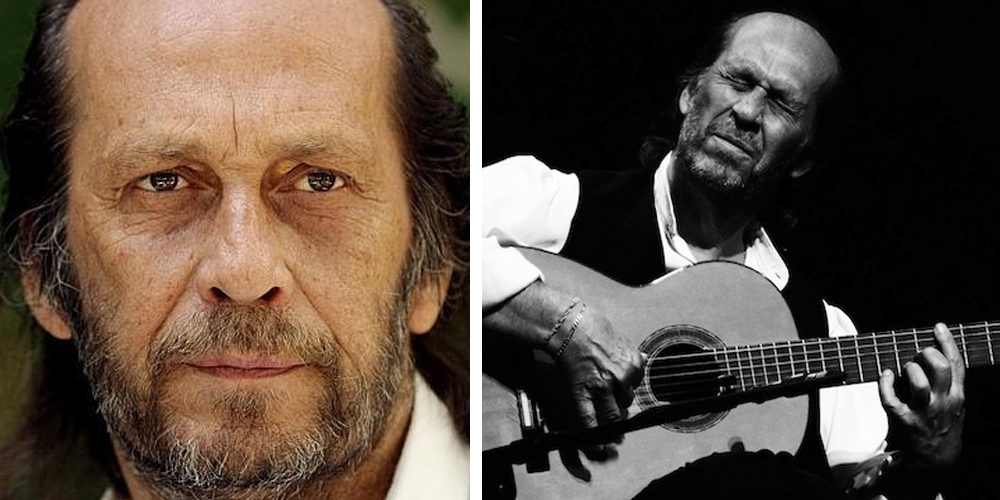

5 cosas que quizá no supieras sobre Paco de Lucía / 5 things you may not have known about Paco de Lucía

Paco de Lucía es uno de los músicos españoles más conocidos del mundo, y todavía es el primer nombre que viene a la mente cuando se habla de flamenco. Pero el artista gaditano es mucho más que flamenco; aquí 5 apuntes para que lo conozcas un poco mejor antes del concierto homenaje que se le dará este miércoles 9 de diciembre en Barbican:

- De madre portuguesa, su nombre completo era Francisco Sánchez Gomes. Como en su pueblo varios otros niños se llamaban Francisco (Paco) y tocaban la guitarra, pasó a ser Paco de Lucía (Paco, el de Lucía) para que se le pudiera distinguir de los demás.

- Igual que ocurriera en su momento con Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, fue el padre de Paco de Lucía quien le encaminó hacia la música profesional desde los 5 años, siendo bastante estricto en la metodología de formación del muchacho y haciéndole practicar más de 5 horas diarias en las épocas intensas.

- Las primeras salidas al extranjero de Paco de Lucía le abrieron a nuevos géneros musicales y propiciaron su interés por otros ritmos, en especial el jazz.

- Fue el creador del llamado “nuevo flamenco”, que incorporaba elementos de otros géneros. Su contribución tuvo muchos detractores entre las filas del flamenco clásico.

- Paco de Lucía fue el primer abanderado comercial del flamenco en el mundo, y el responsable de que esta seña de identidad andaluza se propagara más allá de las fronteras españolas.

Aunque en 2004 redujo notablemente la frecuencia de sus apariciones públicas, ha seguido dando conciertos, especialmente en España y en Alemania, hasta unos meses antes de fallecer el 25 de febrero de 2014.

La comunidad de Barbican prepara un concierto homenaje a Paco de Lucía, este miércoles 9 de dicembre, con la actuación de algunos de los artistas que compartieron escenario y vida con el guitarrista flamenco, así como nombres relevantes en la escena musical internacional. Los detalles sobre el evento están disponibles en este enlace.

_______________________________

Paco de Lucia is one of the world’s most renowned Spanish musicians, and his is still the first name that comes to mind whenever the topic of flamenco is brought up. But the Cadiz region born artist is more than a simple flamenco guitarist; here are 5 details to get to know him a little better. before the Paco de Lucia tribute concert, this coming Wednesday 9 December at Barbican:

- Born to a Portuguese mother, his full name was Francisco Sanchez Gomes. Many other children in the small town where he lived were called Francisco (Paco) and played the guitar. He became Paco de Lucía (Paco, the son of Lucia) so that he could be told apart form the other kids.

- As it had happened with Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart back in the days, it was Paco de Lucia’s father who led the boy to the guitar at age 5. His father was quite strict in everything related to methodology, and the boy used to study up to and over 5 hours a day during intense times.

- The first few musical ventures abroad opened Paco de Lucia up to unheard of musical genres and fostered his interest in other rhythmic solutions, especially jazz.

- He was the creator of «new flamenco», a fusion of classic flamenco sounds with elements of other musical genres. His contribution to the genre had many detractors among the ranks of classic flamenco.

- Paco de Lucia was the first flamenco artist to make flamenco known and broadly available to listeners worldwide, and ultimately the first person responsible for taking this Andalusian signature sound beyond Spanish borders.

Although Paco de Lucia significantly reduced the frequency of his public appearances in 2004, he continued performing, especially in Spain and Germany, until a few months before his death on February 25, 2014.

The Barbican community prepares a tribute to Paco de Lucia this coming Wednesday 9 December, with performances by some of the artists who shared stage with the flamenco guitarist, as well as other leading names in the international music scene. Details about the event are available on this link.