«My experience in Argentina was life-changing and proved decisive in setting me on a career path in music»

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our eighth guest, Helen Glaisher-Hernández, pianist, Latin Classical music expert and artistic director of the Iberian & Latin American Music Society (ILAMS).

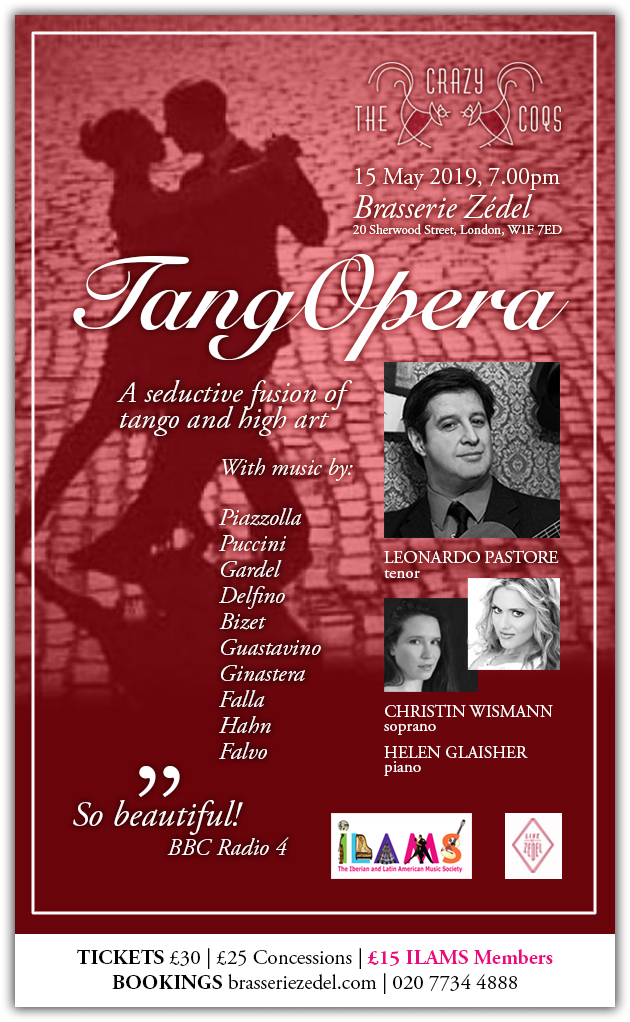

For the past four years, ILAMS and Instituto Cervantes London have co-produced the ECHOES Festival of Latin Classical Music, taking place across some of the capital’s most prestigious classical music venues, such as St Martin-in-the-Fields, the Royal Academy of Music and St James’s Piccadilly.

Following two degrees in Spanish and French at the University of Cambridge (Corpus Christi College), including a year abroad studying Piano at the Conservatorio Nacional Superior in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and an MMus in Piano at Trinity College of Music in London, Glaisher-Hernández now combines her two great loves – music and hispanicity – as a concert pianist, event producer and educator specialising in Luso-Hispanic repertoire.

You often say that your two great loves are music and hispanicity. How do you combine both in your life?

Well, I was born in the UK, in Sheffield, but am also half-Spanish by virtue of my Canarian mother, who is a tinerfeña. As a child, I was quite wilful and typically replied in English whenever my mother spoke to me in Spanish. I understood her perfectly well, though, because she had persevered in speaking her mother tongue to me regardless ever since I was born. (Now my Spanish is near-native, and I feel very grateful that she did!) I perfected my Spanish at secondary school and since this was my absolute favourite A-Level subject, I then opted to read Spanish (and French) at university.

Having also studied piano from the age of four, and achieving an advanced level in my teens, it occurred to me that I could use the requisite ‘Year Abroad’ of my Languages degree to further my playing by studying piano in a Hispanic country. I’d been to Spain so many times by that point, and having never left Europe, South America beckoned to me in a much more enticing way. After investigating the options, I discovered that Argentina housed one of the best musical institutions on the continent, the Conservatorio Nacional Superior ‘López Buchardo’ in Buenos Aires, and the Dean there kindly agreed to let me enrol on the first year of their undergraduate Music degree. My experience there was life-changing and proved decisive in setting me on a career path in music – something I’d never seriously considered until then.

When I returned to England I made plans to audition for music college here after my graduation from university, and was accepted at Trinity College of Music (as it was then known); I wanted to study with a particular tutor there, the Venezuelan pianist, Elena Riu. From the off I played a lot of Luso/Hispanic music with a view to specialising in that repertoire professionally.

…And ten years later that’s essentially what I’m still doing. Of course, I play all sorts of composers (I’m not a Latin ‘fetishist’, as some people seem to think) but with my particular background, and after so many years of studying Hispanic ‘letters’ (including Hispanic literature, film, theatre and visual arts) at university, it gives me a lot of satisfaction to bring my cultural knowledge and experience to performing and promoting this wonderful but highly-neglected music; music which I sincerely believe can count itself amongst the finest ever written anywhere. In fact, I would argue that no non-native musician can authoritatively tackle this repertoire without having enjoyed a considerable level of immersion in the vast, diverse and extremely rich culture that is Hispanic culture. And I would cite cultural understanding (or a lack of it) as the main challenge facing international promoters of Latin classical music today.

Since graduating from Trinity, I feel privileged to have performed at some of the UK’s most prestigious venues, and to have been able to collaborate with some truly great artists from the Latin classical music field. At the moment I’m working on the release of my first album, which explores the globalisation of the tango through its operatic roots. The recording also features the Argentine tenor, Leonardo Pastore, soprano, Jaquelina Livieri, and mezzo-soprano, Florencia Machado – all leading opera singers in Argentina, alongside various instrumentalists from the Buenos Aires Philharmonic. Don’t ask me exactly when it’s coming out, because the Coronavirus pandemic has thrown uncertainty on all our plans, but watch this space!

Since you have a degree in Spanish and French from Cambridge University, did languages open doors to you?

So (without wishing to brag!), I actually have two degrees from Cambridge: an MA in ‘Modern and Medieval Languages’ and an MPhil in ‘European Literature’, which I decided to ‘tag on’ to my first degree before switching to Music. I did this for the entirely flippant reason that all my friends were doing it, and I thought it would be ‘fun’ to continue to maintain some sort of academic activity whilst I took a year to prepare for Music auditions. Of course, as it turned out, the MPhil was very intense and necessarily absorbed most of my time and headspace, and I ended up delaying my musical plans for another year. My MPhil, however, unexpectedly turned out to be one of the best things I’ve ever done. After four years of achieving only average-to-good marks as an undergraduate, I seemed to blossom as a postgraduate, to the extent that the Faculty subsequently offered me funding to stay on for PhD. …But I’d been too seduced by music by that point to abandon my plans. Nonetheless, I now see that year as an essential part of my education, and I particularly enjoyed working on areas such as Argentine film and the plays of Lope de Vega, whilst for my dissertation I explored the Canarian cross-currents present in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. During this year I also studied a considerable amount of Postcolonial Theory, which continues to colour my understanding of the world, and its music, to this day.

As for the opening of doors, I never really contemplated pursuing a career in Languages in the literal sense – the idea of becoming an interpreter, for example, never appealed to me, although I think it almost goes without saying that having Languages can only improve one’s career prospects in any sector. For me, the importance of Languages is not so much utilitarian as humanistic – and increasingly so in these troubled times in which we live. We Brits are infamous throughout the world for our relative reluctance to learn languages, our misplaced indolence predicated on the convenient reality that the rest of the world is more than adept at speaking ours. But instead of bringing increased peace and enlightenment, the new digital century has delivered an overwhelming intensification of globalisation that we are struggling to assimilate, and which has instead only led to culture wars, the hardening of politics and the polarisation of societies worldwide.

The mainstream media have driven public discourse into a narrow dialectic by overwhelmingly tackling these problems as political ones, but in my opinion our problems are fundamentally cultural; the result of a naive and incoherent identity politics (on all sides) spouted by people unversed in any kind of nuanced cultural thinking. A consensus of the population seem to view investment in the cultural industries as a merely optional adjunct to the ‘utilities’ of the economy, but as Winston Churchill eloquently warned us, “Ill fares the race which fails to salute the arts with the reverence and delight which are their due.” I believe that culture is the answer to all our social and political problems. In order to solve the challenges of globalism we must do better at understanding each other – the survival of the planet and our species depend on it. I consider language to be the keystone of any culture, and so in that sense, we must all learn languages. …And by the way, music is also a kind of language!

Your year abroad studying piano at the Conservatorio Nacional Superior in Buenos Aires, how was it?

If I tell you that I really didn’t want to come back at the end of the year, that might give you some sense of how devastatingly incredible it was. I went out there with consciously low expectations, never dreaming that I would literally have the time of my life. I’ve been back to Argentina many times since then, so it seems like a second home now, but I still remember how it felt that first time, and it makes me a little nostalgic to think about it. It was a very special experience that had a profound and lasting effect on my life in many ways.

I think the first time you leave Europe – as a European, I mean – it’s always something of an experience, like landing on a different planet. Argentina is a place where crazy things happen to you. Having said that, I soon felt like I strangely belonged there. Argentinian people are incredible characters, and I was quickly seduced onto their wavelength. To an extent, Argentines have a reputation for being corrupt and duplicitous, but that wasn’t my experience at all, at least not in my personal relationships. On the contrary, I think Argentines are quite simply the best people on the planet – the most generous, witty, intellectual and genuine you’ll ever encounter. Everything runs deep. When they say something, they mean it, and they’re all philosophers, down to the taxi drivers and the person checking out your shopping at the supermarket. They blew my mind constantly; every conversation was a revelation. Once they befriend you, the bond is permanent. I still have a lot of the same friends I made there 17 years ago, and they’re some of the best friends I ever had.

The city, by extension, and despite its size, is also warm and welcoming – it embraces you as you walk down the street. I lived in a student residence with Argentinians from all corners of the country who had also come to study in the capital, as well as a few Brazilians. Supposedly, the building – a traditional 19th-centuy house in the Barrio Norte district – had originally been a brothel, and it was definitely haunted – I had some unusual experiences there! There was never a dull moment.

At the time of my arrival in 2002, Argentina had just been plunged into an economic crisis and the peso had lost more than two thirds of its value overnight. Argentinians suffered terribly, but for me this was effectively like winning the lottery. It meant that me and my pounds sterling could jet-set around the country taking 5-star mini-breaks, and eat out every day of the week. I didn’t have a care in the world. It was nice to temporarily feel the liberating effects of relative wealth, although thinking about it now, it does seem a little decadent given what was going on around me.

Studying at a conservatoire for the very first time was also an awe-inspiring experience. …Bearing in mind that I was probably the first Briton to ever study there in the history of the institution. My fellow students couldn’t quite understand why on earth I would leave England to go there. I was something of a curiosity, and all the students knew who I was and wanted to be my friend. (It’s my conclusion that Argentines have a profound admiration for the British. Although they often pretend to hate us, I think they’d secretly like to be us.) I had a wonderful piano teacher, Graciela Beretervide (a former student of Arrau), with whom I studied Handel, Beethoven, Chopin and Rachmaninov. She was like a mother to me, and we still keep in touch. I also attended all the first-year modules in subjects such as Critical Theory, Musical Forms, Gregorian Chant, Alexander Technique, and so on. Studying classical Music History from the point of view of the third world, for example, was very eye-opening. The best part was that, not being a permanent student, I didn’t have to actually sit any of the exams, so I just dedicated myself to taking it all in and having a great time! By night I went out to all sorts of concerts with my friends.

It was a beautiful time. I walked around in a constant state of euphoria, with a permanent smile on my face. But it was ultimately an artificial situation which inevitably had to end. Coming back to England to do my finals was, by comparison, pretty depressing. But as Eladia Blázquez said in her famous tango, ‘siempe se vuelve a Buenos Aires’. (‘You always go back to Buenos Aires’.) And so I have, several times, and I’m sure I wild find myself there again…

How did you start to appreciate the music of different cultures and traditions from an early age?

Mainly because my father was British and my mother is Spanish, and they each tended to listen to very different things. My mother liked to have Canarian folk music on in the background, and other types of Hispanic music – Mocedades, Julio Iglesias, Rocío Jurado…as well as Latin American artists such as Mercedes Sosa, Los Panchos and Los Paraguayos.

My father, being of a slightly older generation to my mother, played a lot of music from the 1940s onwards – Glen Miller and big-band swing music, George Formby, crooners like Bing Crosby, Hollywood musicals… He also liked the pop music of the 60s and 70s. In his record collection he had Shirley Bassey, The Carpenters, Burt Bacharach, ABBA, The Bee Gees, Neil Diamond, Neil Sedaka… My father was a businessman by trade, but used to organise concerts for the Variety Club to raise money for charity – he put on huge events around Yorkshire with artists such as Matt Monroe and The Nolan Sisters.

Neither of my parents ever had any kind of musical training, although they were (are) naturally very musical and respectively very decent singers (they were always singing around the house) – I always thought both of them could have been professionals. I think the point at which they intersected musically was Nat King Cole’s En español – an album which now reminds me of them and makes me very sentimental.

In terms of classical music, I was exposed to a lot of the standard orchestral repertoire at the local youth orchestra as a teenager where I played violin, alongside things I heard on Classic FM. During my Sixth Form I also did an ALCM diploma and studied a lot of the ‘Great’ composers.

My elder brother, Mik, was a professional musician, however – he was the drummer in a successful Sheffield band of the 80s and 90s called the Comsat Angels. They had some brilliant songs, the most famous probably ‘Independence Day’. When I was a teenager, Mik would ‘corrupt’ my listening habits by making me mixtapes of the Beatles, and various rock and grunge bands I’d never heard of, like Juliana Hatfield. Obviously at that time my own interests came from what was in the Top 40, i.e. Brit Pop – Pulp (also a Sheffield band) and Radiohead probably the most. Plus any number of pop artists from that time; my biggest guilty secret being Bon Jovi. (Still is.)

As a teenager I also had musical escapades in Spain each summer when my parents would send me off to Tenerife to spend the holidays at my grandparents’ house. My aunties used to take me out clubbing with their friends and we danced to a lot of salsa. A lot of the Latin pop they played on the radio also rubbed off on me. Mónica Naranjo, Juanes, Alejandro Sanz…

You could say that my musical tastes have become very eclectic, but I only really divide music into two types: good and bad. But I like to keep an open mind and am always listening to new things. I would say music is my addiction.

You have a special passion for chamber music and vocal accompaniment. How did you become interested?

I first ‘discovered’ the beautiful thing that is chamber music at the conservatoire in Argentina. We had a weekly chamber music class in which we all had to form small ensembles and perform in front of each other. There was also a strong feeling of solidarity within the class which helped to convert me. As a pianist, the concept of playing with other people was entirely new to me. The life of a pianist is a relatively solitary one, and you really need a certain ego and temperament to want to perform publicly as a soloist – a temperament I don’t really possess. I find the experience a bit like navel-gazing in public, whereas when you collaborate with others it’s a more sociable and humbling experience. …Plus you get the benefit of seeing things from different perspectives.

I didn’t really get into vocal accompaniment until I got to Trinity, when I was approached by a soprano who was into some of the same things that I was. I’d never really had any particular interest in vocal music before then – you would have literally had to drag me by the hair to see an opera. But the more I got into it, the more I began to appreciate the marvel that is the human voice and the incredible technical feats that classical singers perform. I’ve come to agree with Avro Part, who famously said that ‘the human voice is the most perfect instrument of all’. At first I didn’t quite know how to listen discerningly to a singer (most people don’t); it was something I’ve learnt to do gradually, and I’m still learning. Now I envy singers – I really wish I could do what they do. Perhaps in my next life I’ll come back as a singer…As for this one, I’m quite content to enjoy it vicariously through the various singers I work with, and I’ve been lucky to play with some really great ones.

You have performed live at major London venues, including the Southbank Centre’s Purcell Room at Queen Elizabeth Hall, Barbican’s Milton Court Concert Hall, St John’s Smith Square, St Martin-in-the-Fields. Which one is the most special for you?

All of these venues are special in their own way and I love them all, but I would actually cite one you didn’t mention: the National Gallery in London. In 2015, I curated a concert titled Music in the Time of Goya in tandem with the blockbuster exhibition, Goya: the Portraits. In addition to being able to work with the acclaimed flamenco dancer, Nina Corti, who provided some bespoke choreographies to accompany the pieces, it was quite magical to be able to play 18th-century music at the Gallery’s illustrious Barry Rooms, surrounded by masterpieces from the same period, where Myra Hess also used to present her historic lunchtime wartime concerts. It’s a beautiful thing when art forms can converge and combine to work in synergy with the surrounding space. It also makes for a more ‘total’ experience for the audience. The project has its own website where you can view video clips and images from the performance, as well as images of some of the Goya paintings featured in the exhibition: musicinthetimeofgoya.com

You also work as Artistic Director of ILAMS in promoting Iberian classical music in the UK. What events do you curate? How did you become involved?

To answer your second question first: I started volunteering for ILAMS whilst I was still a student at Trinity. I came across the Society whilst promoting a concert I was organising, and asked the committee if they would advertise the event to their members. A few representatives from the Society came along to my concert, and on seeing that I had a pretty good turn-out I guess they thought I could be of some use to the organisation. I joined the committee in 2006, and when in 2008 the then Chairman left ILAMS, I was voted in as his successor.

Since then, the Society has developed considerably in many ways, although it remains a modest, grass-roots organisation. Our activities are now basically divided into three strands: our monthly lunchtime concert series at St Martin-in-the-Fields and St James’s Piccadilly; our bi-monthly classical guitar series, Guitarrísimo, and our annual Echoes Festival.

The complete ILAMS programme archive is viewable on the Society website, and there is also a highlights page. Personal favourites for me include presenting artists and ensembles such as Celso Machado, Leo Brouwer, John Williams, Bárbara Llanes, Onix, Marcelo Bratke, Jesús León, Coro Cervantes, Cecilia Rodrigo, Thibaut García, Douglas Riva, Moreno Gistaín Duo, Aquarelle Guitar Quartet, Lena Semenova, Jacquelina Livieri, Alvaro Pierri and the Mela Guitar Quartet, amongst many others.

You also organise Echoes Festival every year. How did it start? Can you share some great moments from these years with us?

Echoes Festival was born out of a mounting practical necessity to consolidate the limited human and financial resources of the Society, since we were previously spreading ourselves across the year with a more ad hoc programme of events which were quite disparate. We also wanted a way of focusing public attention on our activities in a more concentrated and singular way, which was facilitated by putting together all of our evening events under one umbrella. Futhermore, in 2016, the year we launched the Festival, there wasn’t (and still isn’t) an annual Festival of Latin classical music in the UK, so it seemed obvious to go in this direction.

All of the programmes from the last four editions of the Festival are available to view on the Festival website. It’s difficult for me to single out any favourite concerts because we have made a concerted effort from the start to programme artists of only the highest calibre, and even within that remit I have often been surprised at the high level we have witnessed. Of course, we’re proud to have featured more widely-known artists from the Iberican classical music circuit, such as the Quiroga Quartet, the Assad Brothers, Odaline de la Martínez and La Grande Chapelle. But some of our younger or lesser-known artists have often been equally beguiling, such as Dichos Diabolos, and the Lacock Scholars. For me, it’s also so valuable to be able to hear some of the best native specialists presenting their national repertoire – such as Venezuelan pianist, Clara Rodríguez, performing the music of her compatriot Antonio Estévez, or Alessandro Santoro performing pieces by his father, Claudio Santoro, that he grew up hearing around the house. Other events have stood out for me because of the holistic experience of hearing music in more quirky and edgy venues: pianist Carla Ruaro performing Amazonian music in the dark depths of the Brunel Tunnel, the concrete floor strewn with leaves; guitarist Darío Barozzi at the historic Cinema Museum, where Charlie Chaplin grew up.

From your experience working with ILAMS and ECHOES, do you think the interest in Iberian classical music among the British public has increased?

I’d like to think that with all the energy that ILAMS has put into our work since 1997, when the Society was founded, we have obviously had a positive impact on the reception of this music. We certainly have a much larger mailing list now than when we started, and our public has grown considerably, with capacity audiences becoming more commonplace at our events. But in broader terms, the wider impact of these things is difficult to quantify. Overall, I think animosity towards this music continues to persist amongst British audiences to the extent that we are still nowhere close to achieving parity of reception with standard European repertoire, and there is therefore still a lot of work left to do.

My sense is that it still takes the really heavy guns to make a systemic difference to the landscape: it requires the superstars of classical music – the Placido Domingos and Gustavo Dudamels of the industry – to present music at major venues and to be featured in the mainsteam classical media to really create significant shifts in public tastes; sadly, the music seems unable to do this purely on its own merits. But I think it’s understandable to a point – it’s human nature to eschew the unknown (and I’m as guilty as most people in this respect). What is always encouraging, however, is that in cases where audiences have been convinced to attend an event, their response to the music is overwhelmingly positive; certainly when ILAMS presents unfamiliar music it invariably goes down very well. Once people are exposed to this repertoire they tend to like it, so the music itself is not the problem; the challenge lies in convincing people to go and hear something they’re unfamiliar with in the first place – especially if they have to part with their hard-earned cash to do so.

«I cannot stress enough how important modern languages research is today»

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our seventh guest, Catherine Davies, is Director of the Institute of Modern Languages Research (IMLR) since 2014. Davies was also Professor of Hispanic and Latin American Studies at the University of Nottingham (since 2004), where she was Head of the School of Modern Languages and Cultures.

After gaining her PhD (Glasgow) in 1984, Davies taught and researched at the universities of Manchester, Queen Mary and St Andrews. Davies has held several research grants funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the British Academy and the Leverhulme Trust.

Her research expertise is in the culture, history and literature of Spain and Spanish America in the 19th and 20th centuries, with a particular focus on Galicia (Spain), Cuba and Argentina. Her publications examine the construction of gender identities and the roles of women in the Spanish American Wars of Independence from Spain (1810s-1820s).

– You have been the Institute of Modern Languages Research (IMLR) director since August 2014, how have these years been? What do you value the most from this experience?

The IMLR is funded by the government and the University of London to support research in Modern Languages across the UK. The aim is to create a space for academic discussion around research, rather than teaching or administration, to lead on new initiatives, and to collaborate as much as possible with non-academic partners to establish strong networks and facilitate public engagement around ML research. Looking back, my job as Director has been mainly working with people from many different backgrounds, including university colleagues, to create sustainable partnerships with definite research outcomes, which I hope have benefited the ML community in general. I loved every minute of it, and I’ll miss meeting so many interesting people and getting involved in many different types of organisations. The experience really opened my eyes to the significance of language expertise across all sectors of society.

– IMLR and Instituto Cervantes London are long standing partners, how do you describe the relationship between both institutions?

We work together very closely, especially since Ignacio Peyró took up his post. My own research is in what I still refer to as ‘Hispanic Studies’, so I personally have always valued highly the Cervantes, both in London and in the 1990s in Manchester. When I was Head of the Spanish and Portuguese Department in Manchester University we arranged for the Cervantes to teach some of our language classes. At the IMLR the relationship is all to do with collaboration in research and outreach. If, for example, the Cervantes is hosting a visiting speaker, the IMLR can organise a research workshop with the speaker on a theme of interest to the UK research community and provide the catering and publicity. Or the IMLR might take an idea to the Cervantes and together we make it happen. We each have our own networks, contacts and influences and join forces whenever we can. The IMLR has a similar relationship with the Goethe, French and Italian Cultural Institutes, and several Embassies.

– How could you describe the importance of modern languages research in a multilingual and globalised world?

I cannot stress enough how important modern languages research is today. Language expertise is vital for international understanding and cross-cultural exchange. Research in the written and visual cultures of non-Anglophone societies, which is where most Modern Language researchers focus their attention, is increasingly urgent. For example, how have the different countries and cultural communities reacted to the Covid-19 crisis? How can we possibly understand this without expertise in languages and cultural sensitivities? Modern Languages research has always been strong in the UK but the discipline is facing difficulties in university recruitment. Entrants to study Modern Languages degrees have steadily decreased since the mid-2000s, especially in German and French, and many Modern Languages units have closed over the last decade. This is not good news for the UK, now facing Brexit and the need for international trade deals, not to mention fighting a global pandemic and finding a new role in the global economy.

– Since you gained your PhD at the University of Glasgow in 1984, you have taught at the universities of St Andrews, Manchester and Queen Mary, among others. Do you see a bigger interest in learning languages?

If you take the long-view, I would say there is as much interest in learning languages in UK Higher Education as ever, but students are tending to take degrees in other subjects, such as Science or Law, and to study a language in the University Language Centres (what we call University Wide Provision). They may not reach the same level of expertise as those who take languages degrees, but they often come back to the language later in life. The number of university students taking languages in the 1980s and 1990s was relatively small, especially in Spanish, much smaller than today, and they tended to study French and German with Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and Russian as minor subjects. Then there was a steady increase in the late 1990s and early 2000s (during the Labour government and university expansion), and a gradual shift from French and German to Spanish and Chinese. I remember when I was Head of the School of Modern Languages and Cultures at the University of Nottingham, recruitment was not an issue until the around 2012. In fact, the concern was that we didn’t have sufficient staff to teach the numbers of students taking Spanish and Portuguese.

– Your research interests include gender and nationalism in Cuba and Spain, particularly the formation and transmission of liberal thought in 19th-century Spanish and Spanish American literature and cultural history. How did you become interested in this topic?

My research on gender, politics and nationalism began with my PhD, at the University of Glasgow, on the Galician author Rosalía de Castro. This was the subject of my first book, published by Galaxia in Galician in 1987. I sent my thesis to Ramón Piñeiro through the post (no digital files in those days) and a box of books arrived three years later. I never found out who the translators were, and it has never been published in English. At the time, it was generally assumed that Rosalía de Castro was a big name in Cuba, but when I went to Cuba to research this further, I realised this wasn’t the case. She may have been important in the nineteenth century among the Galician migrants, but in Castro’s Cuba she was virtually forgotten. I published a book on Cuban women writers, and an edition of the 1846 abolitionist novel, Sab, written by the Cuban/Spanish author, Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda. This led to an interest in the work of Spanish abolitionist, Rafael María Labra, who was born in Havana but whose family were Asturian. His father was in the Spanish army and governor of Cienfuegos; there is still a gleaming white statue of the father, Ramón, in the central square today.

– You also wrote a number of books including on abolitionism in Cuba and co-wrote South American Independence: Gender, Politics, Text. What are you currently working on?

I have always been interested in the published writings of women in nineteenth-century Spain and Spanish America. I find it is impossible to come to grips with these texts without fully understanding the social and political circumstances of the times. The earliest women’s writings in nineteenth-century Spanish America are by women who were inevitably caught up in the Wars of Independence from Spain, between 1810 and 1830 more or less. I led a research project on this subject and we created a map-based database of hundreds of women involved in the wars hosted by the University of Nottingham: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/genderlatam

My own research for the co-authored book you refer to focused on the writings of the Colombian Josefa de Acevedo and Argentine, Juan de Manso. The 1820s was a pivotal decade in Spanish America, everything changed. I’m now working on the travelogues written by British travellers to the River Plate in the 1820s, texts written in English but translated into Spanish and published in Argentina in the 1920s. The books written by the ‘viajeros ingleses’ are very well known in Argentina but almost forgotten in the UK. Although written by sea captains, army officers and company agents they are beautifully crafted literary texts but are only used now and then by British historians seeking factual data.