«I cannot stress enough how important modern languages research is today»

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our seventh guest, Catherine Davies, is Director of the Institute of Modern Languages Research (IMLR) since 2014. Davies was also Professor of Hispanic and Latin American Studies at the University of Nottingham (since 2004), where she was Head of the School of Modern Languages and Cultures.

After gaining her PhD (Glasgow) in 1984, Davies taught and researched at the universities of Manchester, Queen Mary and St Andrews. Davies has held several research grants funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, the British Academy and the Leverhulme Trust.

Her research expertise is in the culture, history and literature of Spain and Spanish America in the 19th and 20th centuries, with a particular focus on Galicia (Spain), Cuba and Argentina. Her publications examine the construction of gender identities and the roles of women in the Spanish American Wars of Independence from Spain (1810s-1820s).

– You have been the Institute of Modern Languages Research (IMLR) director since August 2014, how have these years been? What do you value the most from this experience?

The IMLR is funded by the government and the University of London to support research in Modern Languages across the UK. The aim is to create a space for academic discussion around research, rather than teaching or administration, to lead on new initiatives, and to collaborate as much as possible with non-academic partners to establish strong networks and facilitate public engagement around ML research. Looking back, my job as Director has been mainly working with people from many different backgrounds, including university colleagues, to create sustainable partnerships with definite research outcomes, which I hope have benefited the ML community in general. I loved every minute of it, and I’ll miss meeting so many interesting people and getting involved in many different types of organisations. The experience really opened my eyes to the significance of language expertise across all sectors of society.

– IMLR and Instituto Cervantes London are long standing partners, how do you describe the relationship between both institutions?

We work together very closely, especially since Ignacio Peyró took up his post. My own research is in what I still refer to as ‘Hispanic Studies’, so I personally have always valued highly the Cervantes, both in London and in the 1990s in Manchester. When I was Head of the Spanish and Portuguese Department in Manchester University we arranged for the Cervantes to teach some of our language classes. At the IMLR the relationship is all to do with collaboration in research and outreach. If, for example, the Cervantes is hosting a visiting speaker, the IMLR can organise a research workshop with the speaker on a theme of interest to the UK research community and provide the catering and publicity. Or the IMLR might take an idea to the Cervantes and together we make it happen. We each have our own networks, contacts and influences and join forces whenever we can. The IMLR has a similar relationship with the Goethe, French and Italian Cultural Institutes, and several Embassies.

– How could you describe the importance of modern languages research in a multilingual and globalised world?

I cannot stress enough how important modern languages research is today. Language expertise is vital for international understanding and cross-cultural exchange. Research in the written and visual cultures of non-Anglophone societies, which is where most Modern Language researchers focus their attention, is increasingly urgent. For example, how have the different countries and cultural communities reacted to the Covid-19 crisis? How can we possibly understand this without expertise in languages and cultural sensitivities? Modern Languages research has always been strong in the UK but the discipline is facing difficulties in university recruitment. Entrants to study Modern Languages degrees have steadily decreased since the mid-2000s, especially in German and French, and many Modern Languages units have closed over the last decade. This is not good news for the UK, now facing Brexit and the need for international trade deals, not to mention fighting a global pandemic and finding a new role in the global economy.

– Since you gained your PhD at the University of Glasgow in 1984, you have taught at the universities of St Andrews, Manchester and Queen Mary, among others. Do you see a bigger interest in learning languages?

If you take the long-view, I would say there is as much interest in learning languages in UK Higher Education as ever, but students are tending to take degrees in other subjects, such as Science or Law, and to study a language in the University Language Centres (what we call University Wide Provision). They may not reach the same level of expertise as those who take languages degrees, but they often come back to the language later in life. The number of university students taking languages in the 1980s and 1990s was relatively small, especially in Spanish, much smaller than today, and they tended to study French and German with Spanish, Portuguese, Italian and Russian as minor subjects. Then there was a steady increase in the late 1990s and early 2000s (during the Labour government and university expansion), and a gradual shift from French and German to Spanish and Chinese. I remember when I was Head of the School of Modern Languages and Cultures at the University of Nottingham, recruitment was not an issue until the around 2012. In fact, the concern was that we didn’t have sufficient staff to teach the numbers of students taking Spanish and Portuguese.

– Your research interests include gender and nationalism in Cuba and Spain, particularly the formation and transmission of liberal thought in 19th-century Spanish and Spanish American literature and cultural history. How did you become interested in this topic?

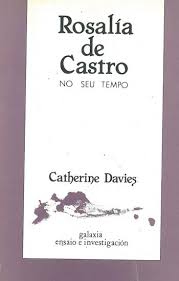

My research on gender, politics and nationalism began with my PhD, at the University of Glasgow, on the Galician author Rosalía de Castro. This was the subject of my first book, published by Galaxia in Galician in 1987. I sent my thesis to Ramón Piñeiro through the post (no digital files in those days) and a box of books arrived three years later. I never found out who the translators were, and it has never been published in English. At the time, it was generally assumed that Rosalía de Castro was a big name in Cuba, but when I went to Cuba to research this further, I realised this wasn’t the case. She may have been important in the nineteenth century among the Galician migrants, but in Castro’s Cuba she was virtually forgotten. I published a book on Cuban women writers, and an edition of the 1846 abolitionist novel, Sab, written by the Cuban/Spanish author, Gertrudis Gómez de Avellaneda. This led to an interest in the work of Spanish abolitionist, Rafael María Labra, who was born in Havana but whose family were Asturian. His father was in the Spanish army and governor of Cienfuegos; there is still a gleaming white statue of the father, Ramón, in the central square today.

– You also wrote a number of books including on abolitionism in Cuba and co-wrote South American Independence: Gender, Politics, Text. What are you currently working on?

I have always been interested in the published writings of women in nineteenth-century Spain and Spanish America. I find it is impossible to come to grips with these texts without fully understanding the social and political circumstances of the times. The earliest women’s writings in nineteenth-century Spanish America are by women who were inevitably caught up in the Wars of Independence from Spain, between 1810 and 1830 more or less. I led a research project on this subject and we created a map-based database of hundreds of women involved in the wars hosted by the University of Nottingham: https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/genderlatam

My own research for the co-authored book you refer to focused on the writings of the Colombian Josefa de Acevedo and Argentine, Juan de Manso. The 1820s was a pivotal decade in Spanish America, everything changed. I’m now working on the travelogues written by British travellers to the River Plate in the 1820s, texts written in English but translated into Spanish and published in Argentina in the 1920s. The books written by the ‘viajeros ingleses’ are very well known in Argentina but almost forgotten in the UK. Although written by sea captains, army officers and company agents they are beautifully crafted literary texts but are only used now and then by British historians seeking factual data.