The benefits of Spanish as a second language

Book a free demo class now

In the age of global business, the value of employees being able to speak more than one language has increasingly been highlighted over the last few years. Multilingual employees earn more money and have «practical benefits in a globalized economy».

Despite the fact that The United States is now the world’s second largest Spanish-speaking country after Mexico, many American people still monolingual.

Truth be told, being bilingual or mulitlingual has also many personal benefits. From being better at multi-tasking to decision making, sharper reasoning, holding off the onset of Alzheimer and being able to see or read about situations from a different perspective or cultural point of view.

Unfortunately many still don’t see the real need for a native English speaker to go out of their comfort zone and learn a second language.

Comfort is easy. We fear uncertainty and so we seek to cushion ourselves in artificial climate-controlled boxes safe from unwanted intrusions. But this is unfortunate. Personal discovery and personal development happen only outside our comfort zone.

When it comes to language learning we create tons of excuses to avoid getting out of our comfort zone: «I’m too old to learn a second language», «I haven’t enough memory to study,» «I’ll sound silly speaking another language,» «They will laugh at me,» etc. But if we take a moment to look back, we see that our life is a sequence of firsts. There’s a first time for everything. And we’ve always felt fear and uncertainty. It’s time to beat language-learning frustration, reach your goals and enjoy a new world of opportunities.

Book a free demo class now

El español es un idioma, no veintidós / Spanish is one language, not twenty-two

Muchos estudiantes de español en Estados Unidos suelen preguntar cuál es el mejor español que deben aprender, como si existiesen mejores y peores versiones del idioma. Las buenas noticias para estos estudiantes es que el español es un solo idioma, y no veintidós (el número de países donde el español es el idioma oficial).

Al igual que el inglés, el español se habla en varios países. Y, tal como ocurre con el inglés, existen variantes locales. Sin embargo, las diferencias entre estas variantes no son tan importantes como para considerarlas dialectos.

Del mismo modo quIe un estadounidense entiende perfectamente a un australiano o a un británico, pero no habla igual que ellos, un hispanohablante entiende a todos los demás. Cada país hispanohablante tiene su propia variante del idioma, pero en general estas variantes tienen más similitudes que diferencias.

Pero más a menudo de lo deseable nos encontramos con escuelas o herramientas de aprendizaje en línea que ofrecen cursos de español diferenciados bajo los nombre de “español de España” y “español de América Latina”. Incluso es fácil encontrar esta distinción en procesadores de texto muy populares que todos utilizamos rutinariamente. Pues bien, esta diferenciación es, como mucho, una media verdad.

Como es bien sabido, América Latina no es un país, sin muchos (concretamente son 19 los que hablan español), y en cada uno de ellos podemos encontrar diferencias en su habla (Argentina, México, Colombia, etc., cada uno tiene su particular variante). Lo mismo sucede con algunas variantes del inglés en Estados Unidos y eso no significa que sean diferentes dialectos o que una sea mejor que otra.

En segundo lugar, la pronunciación del español es muy consistente. Más incluso que la del inglés. ¿Sorprendidos? Lo cierto es que entre regiones hispanohablantes hay menos diferencias que entre regiones anglohablantes. Las diferencias más destacadas en pronunciación son las ya conocidas por todos: la pronunciación de la “z” y la “c” en ciertas partes de España, que en América Latina se pronuncian como una “s”.

No obstante, es justo destacar que también existen algunas diferencias más importantes. Especialmente en vocabulario. Algunas palabras tienen significados diferentes en diferentes regiones, no sólo es un tema de España y América Latina.

Otro asunto diferenciador es el uso de la conjugación del “vosotros”, que se usa en España pero no en América Latina, donde usan “ustedes”. Pero la realidad es que está diferencia se ha magnificado demasiado. La experiencia del Instituto Cervantes indica que los estudiantes no tienen ningún problema para aprender ambas formas.

En conclusión: no importa qué variante del español se estudie, ya que al final será la herramienta perfecta para comunicarse con los hispanohablantes de todo el mundo. Porque el español, como cualquier otra lengua, es esencialmente una herramienta extremadamente flexible para entendernos los unos a los otros sin importar nuestra nacionalidad o cultura.

————————————————————————————————————————————————————————–

At some point, many students of Spanish in the US have asked the question above and wondered whether the Spanish they have heard is the “real” Spanish or just a dialect. Well, we have good news for you: Spanish is one language, not twenty two (the number of countries where Spanish is an official language).

Like English, Spanish is spoken in many different countries. And just as it happens with English, there are local variants – though the differences are not so great that they become different dialects.

If you are from the United States, you can understand an Australian or a British person, right? But you don’t speak like them. The same happens with Spanish. Each Spanish-speaking nation speaks its own variety of Spanish, but overall they have more similarities than differences.

More often than it should be, you probably have come across some language schools or online tools in the US offering differentiated Spanish courses under «Spanish (Spain)» and «Spanish (Latin America)». You can even find this differentiation in very famous word processors, for example. Well, at most, this is a half-truth.

Firstly, as you well know, the Spanish speaking Latin America is not one country but nineteen, and you can find differences between them in the same way that you can notice different English variants between states in the US.

And secondly, Spanish pronunciation is pretty consistent, much more than the pronunciation of English. That is, the differences in pronunciation, from region to region, are less for Spanish than they are for English. Surprised? The most noticeable difference regarding pronunciation in Spain as compared to Latin America is the pronunciation of the letters «z» and «c» – which in Latin America are pronounced like the letter «s» but in Spain are pronounced like «th». For the majority of students this difference is minor and of little consequence.

However, it is fair to say that there are also bigger variations, especially in vocabulary. Certain words carry different meanings in different areas. Not just Spain vs. Latin America, but region to region. The same is true regarding certain expressions; some are used in some regions, and others are used in different regions.

Another issue is the «vosotros» conjugation, which is used in Spain, but not in Latin America, where they use “ustedes”. The reality is that too much is made out of this issue. The experience at Instituto Cervantes says that students understand easily both forms.

The Bottom Line

No matter which variant of Spanish a student learns, at the end of the day it’s going to be the perfect tool to communicate with Spanish speakers all over the world. Because Spanish as any other language is just a tool, a very flexible tool, to understand each other regardless of nationality or background.

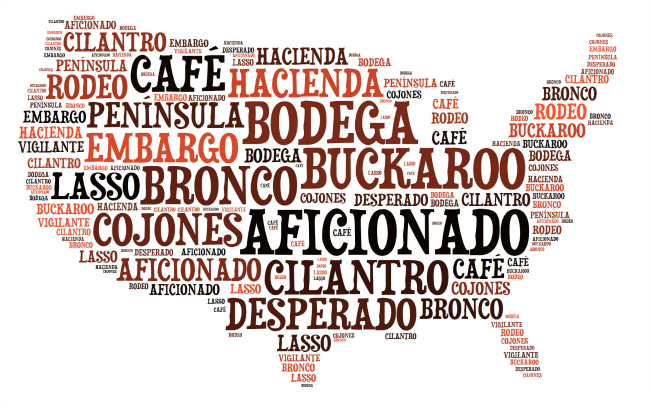

10 palabras procedentes del español que usas en inglés / 10 Spanish Words You Might Not Know You’re Using

Probablemente el inglés sea el idioma que más palabras y términos ha exportado a otras lenguas, sin embargo el proceso inverso también se produce. Especialmente destacable es la influencia del español en el inglés de los Estados Unidos. Tanto por motivos históricos como por la creciente comunidad hispanohablante en Estados Unidos, es inevitable que ambas lenguas tomen prestadas palabras y expresiones la una de la otra. Veamos algunas de las más comunes:

-Aficionado. Significa exactamente lo mismo que en español. En Nueva York podrás encontrar a un gran número de wine aficionados.

-Bodega. Esta palabra la oirás principalmente en Nueva York y tiene un significado ligeramente diferente ya que se refiere a una tienda de comestibles de barrio. En el resto del país no la han adoptado y se utiliza la acepción inglesa corner store.

-Buckaroo. El origen de esta curiosa palabra que se usa como sinónimo de cowboy está en la errónea pronunciación de vaquero. Aunque no se utiliza demasiado, se puede ver empleada en algunas películas y novelas.

-Cilantro. Cada vez se utiliza más el término en español para referirse a una de las especias más utilizadas en la comida norteamericana, aunque el inglés tiene el término coriander.

-Cojones. En inglés se utilizan los castizos cojones en su acepción de valor o coraje, desprovista del matiz soez que puede tener en español. Curiosamente esta palabra está especialmente valorada en el mundo político estadounidense.

-Desperado. Un desperado es para los americanos un criminal temerario y audaz que proliferaba mucho durante los primeros años del salvaje oeste americano. Su origen está en la palabra española desesperado.

-Lasso. En Estados Unidos es una cuerda larga de cuero u otro material con un nudo corredizo en un extremo, utilizado para amarrar caballos, ganado, etc. y viene de la española lazo.

-Mano a mano. Esta expresión española se utiliza en inglés para referirse a una “confrontación directa o un duelo entre dos partes”.

-Rodeo. El deporte favorito de los tejanos debe su nombre a que en las colonias españolas de América el rodeo fue el proceso utilizado por los vaqueros para reunir el ganado.

-Vigilante. En Estados Unidos un vigilante es cualquiera que se tome la ley por su mano para vengar algún crimen anterior.

Hay muchas más palabras y expresiones del español que han encontrado acomodo en el inglés. ¿Se os ocurre alguna más?

Without a doubt, English is the language that most words and terms has exported to other languages, but it’s a 2-way street and English speakers also use words imported from other languages. Especially noteworthy is the influence of the Spanish in the US English. The reasons for that are several: the presence of Spaniards during past centuries left an undeniable legacy, but also the growing of the Latin community in the United States is having a deep impact on the way people talk. It is inevitable that both languages borrow words and expressions from each other. Here are some of the most common Spanish words English speakers might not know they’re using:

– Aficionado. It means exactly the same thing in Spanish. In New York you can find a large amount of wine aficionados, for example.

-Bodega. You will hear this word mostly in New York and has a slightly different meaning from the Spanish word since it’s referred to a grocery store and not only to a liquor store. In the rest of the US bodega has not been adopted.

-Buckaroo. The origin of this funny word -used as a synonym for cowboy of de Great Basin and California Region- is in the wrong pronunciation of the Spanish word vaquero.

-Cilantro. This a interesting case. Although English has its own word for this herb (coriander), the use of the Spanish word cilantro is becoming more and more popular.

-Cojones. This powerful and sometimes rude Spanish word is used in English in the sense of value or courage. Interestingly this word is particularly popular in the American political world.

-Desperado. This word was the name given to these audacious criminals who proliferated greatly during the early years of the American Wild West. Its true origin is in the Spanish word desesperado which means desperate.

-Lasso. This is the word used in US to define a long string of leather or other material with a noose at one end, used mainly to tie horses , cattle, etc… You can find its true origin in the Spanish word lazo, meaning tie.

– Mano a mano. This Spanish phrase is used in English to refer to a «direct confrontation or a duel between two parties.» Its literal translation is “hand to hand”.

– Rodeo. The favorite sport of Texans owes its name to the Spanish colonies in America. The rodeo was the process used by cowboys to herd the cattle.

-Vigilante. In the United States a vigilante is anyone who takes the law into his own hands and fights against the crime. In Spanish vigilante means watchman.

There are many more Spanish words and expressions you can find in the English language. Can you think of any more?

V Jornada de formación de profesores: español como lengua heredada / V Workshop for Teachers: Spanish as a Heritage Language

El Instituto Cervantes, con la colaboración de NYU, organizará el próximo 22 de marzo de 10h a 14h la V Jornada para profesores de español sobre la enseñanza del español como lengua heredada dentro del contexto de enseñanza K-12.

¿Cómo adaptar una clase para estudiantes de español que han crecido con el idioma en casa? ¿Cómo mantener la atención de estos estudiantes en clase? ¿Qué contenidos se les puede enseñar?¿Cómo potenciar el hecho de que hablen dos lenguas teniendo en cuenta su componente afectivo? Éstas son algunas de las cuestiones que se tratarán en la próxima jornada de profesores.

Los ponentes son especialistas de la talla de Kim Potowski, profesora de lingüística hispánica en la Universidad de Illinois en Chicago, y Karen Beeman, formadora de maestros y directores a nivel nacional y miembro del Illinois Resource Center.

El curso combinará teoría y práctica y se hará especial hincapié en la reflexión. Además, todos los participantes recibirán un certificado de asistencia.

Consulta el programa del curso aquí

Inscríbete aquí

Instituto Cervantes in collaboration with NYU, this upcoming March 22nd from 10AM to 2PM will hold the 5th Workshop for Spanish teachers about the teaching of Spanish as a heritage language in grades K-12.

How do you design courses for Spanish students that have grown up with the language in their home? How do you keep these students engaged? What areas should you focus your lessons on? How do teachers maximize the benefit that these students speak both languages? These are just some of the questions that will be covered in this next workshop.

The speakers are experts in this field, and include Kim Potowski, Professor of Spanish Linguistics from the University of Illinois at Chicago, and Karen Beeman, educational specialist and advocate from the Illinois Resource Center.

The course will combine theory and practice and will provide specific emphasis on reflection. All participants will receive a certificate of participation.

View the program here.

You can register in person at ICNY, by phone (212-308-7720) or online here.