«British architects have great respect for the Spanish and the knowledge they bring to their practices»

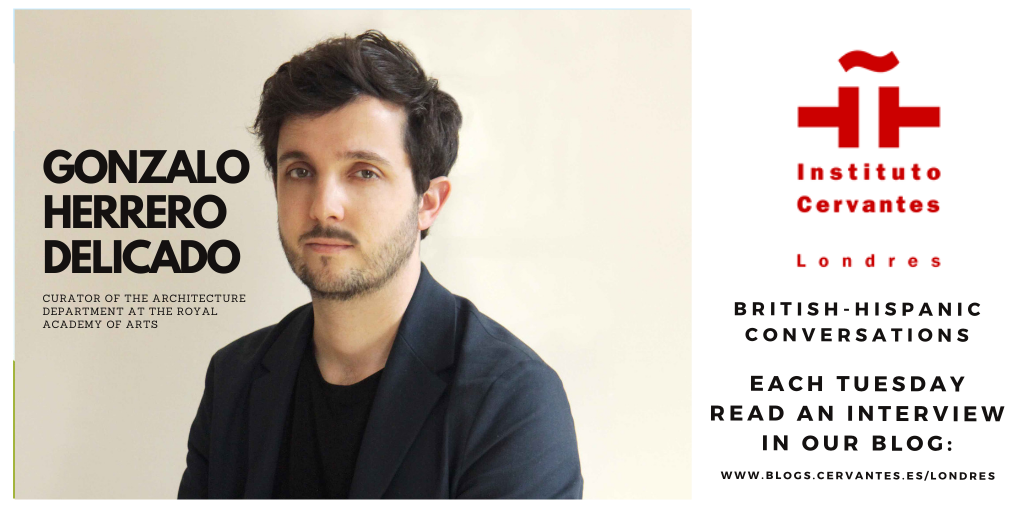

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our third guest, Gonzalo Herrero Delicado, is an architect, curator and writer based in London. He is Curator of the Architecture Department at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) where he works on a wide range of projects including exhibitions, displays and talks around architecture and its connection to wider visual arts, technology and design.

Herrero Delicado curated the opening programme for RA’s Architecture Studio Invisible Landscapes (2018-2019), a series of commissioned installations exploring how digital technologies are transforming our everyday lives and environments. Furthermore, last year he worked on a major show titled Eco-Visionaries, exploring the ecological impact of human action on the environment through modern art, architecture and design practices.

Previously, Herrero Delicado held other curatorial positions at The Architecture Foundation and the Design Museum, both in London. At The Architecture Foundation he was the curator of the institution’s public programme which included the Architecture on Film, organised in partnership with the Barbican. At The Design Museum, he managed the curation of a number of commissioned installations as part of the museum’s opening exhibition Fear and Love: Reactions to a Complex World (2016-2017).

As an architect, he worked for several practices, amongst them Lacaton & Vassal Architectes in Paris.

– You have been at the Royal Academy of Arts for almost four years, how do you find it balances with your life?

The balance is very positive and enriching, although it comes with lots of work. My university training is as an architect, and it was through practice that I trained as a curator. I studied at the University of Alicante where the training was very extensive, as well as the range of references that we handled. It was a very humanistic training that made me understand the complexity of architecture and its intimate connection with other disciplines. However, the job of curator involves many other skills that I had to learn on my own. I started as a curator of public programs at The Architecture Foundation in London. Afterwards, I went through the Design Museum and now the Royal Academy. I have gradually focused on exhibitions, which has allowed me to learn about museography little by little as well as organisation and management of exhibitions, conservation, loans, interpretation and everything that goes with being a curator in a museum.

The gradual advance in the scale and complexity of the institutions has also been very positive in this training. I organised my first exhibition on my own as a curator, editor and designer. A great leap compared to the almost 500 people who work directly and indirectly at the Royal Academy. Even so, the feeling is very familiar and we all know each other by name, which makes work and the day-to-day much easier.

– How did Eco-Visionaries, the last exhibition you curated, come about?

Eco-Visionaries was the result of a collaboration with several European museums, including Laboral in Gijón and Matadero in Madrid. A transnational exhibition that explored how artists, architects and designers are reflecting on climate change to propose alternative ways of relating between humans and the environment. Eco-Visionaries has been a great opportunity for both the museum and me personally. When I did the interview for this position, I presented a proposal on the anthropocene, and four years later I was able to organise this exhibition – together with Mariana Pestana and Pedro Gadanho. Eco-Visionaries sought to make the public reflect on the impact of our lives in the current environmental crisis. It is something that interests me a lot as a curator, making people reflect on the aspects of our life and the world around us that would otherwise go unnoticed.

– What did this exhibition mean and what impact did it have on you?

Eco-Visionaries attracted the youngest audience out of our exhibitions in recent years and that is tremendously important, particularly when it comes to climate change. It has also been an occasion to redefine our sustainability strategy and generate procedures with a lower environmental impact, something that we want to implement throughout our future program. Regarding this topic, there is still a lot to do. It continues to be an important part of my agenda, either giving talks or collaborating with different projects and foundations such as The Royal Foundation of the Dukes of Cambridge, whom I currently advise with the Earthshot Prize, which is considered the most prestigious award in environmental matters.

– You were 27 years old when you came to London and started working as a curator. How has this experience in the British capital been?

I love London. It is a city in continuous movement and has a frenetic rhythm with events and cultural plans every afternoon of the week. That’s something you can’t find in many other cities. It is something that hooks me, although sometimes it can be exhausting and I understand that it does not work for everyone. Many people come and go in this city, they do not just connect with it and prefer to live in smaller and more relaxed cities. I think that if you do not know how to make the most of the opportunities that the city offers, it is better to look elsewhere, but London can be very demanding and end up devouring you.

– The coronavirus crisis has stopped everything, but what projects are you working on that you can tell us about?

This moment is truly unique. I have had many years without having the time to dedicate myself to research and write. I am taking advantage of this time to advance various projects both inside and outside the Royal Academy. These are very eclectic in both format and theme, ranging from architecture to technology, fashion, and climate change. For example, I have spent several years researching how virtual technologies are transforming architecture and art. In 2017, I started with the Invisible Landscapes project that lasted almost a year and gave rise to a series of installations, a debate program and even a short film in virtual reality. Now I am interested in continuing this exploration and addressing how digital technologies, from social networks to biometrics, are altering and redefining the conventions of our human appreciation of beauty and the spaces dedicated to it.

– What impact does Spanish architecture have in the United Kingdom and vice versa?

In London and the United Kingdom, in general, there are many Spanish architects who work in the main studios. Some also have established their own offices here. The crisis in Spain between 2008 and 2014 had a strong impact. Specially on the real estate sector and therefore, on architects and many of them decided to settle here. English architects have great respect for the Spanish and the knowledge they bring to their practices. Likewise, many others have decided to dedicate themselves to teaching and, in practically all universities with architecture studies, you can find Spanish teachers.

– Most of our readers are Spanish students. Is Spanish spoken at the Royal Academy? And to what extent in the architectural sector?

There are several Spaniards in the Royal Academy, especially in the exhibition department. There are always conversations in Spanish in the hallways and we even had a potato omelette contest. The Royal Academy has always had a connection and appreciation for Spain throughout its history. For example, in 1920 there was an exhibition dedicated to Spanish painting with works by El Greco, Velázquez, Zurbarán and Goya among others, and whose selection was made by a committee chaired by the Duke of Alba. More recently we have had other exhibitions with Spanish artists such as Dalí / Duchamp (2017-2018) and Picasso and Paper (2020). Regarding architecture, one of the last collaborations with Spanish architects was the installation of Home (Act I) with the Barcelona studio MAIO which I curated as part of the Invisible Landscapes project that the Architecture Studio inaugurated and which is currently part of an exhibition in Matadero in Madrid. Additionally, we even had a Honorary Royal Academician, the Spanish architect Josep Lluís Sert.

– As an architect, what recommendations do you make for everyone who visits or even lives in London?

Without a doubt, a key visit is the house-museum of the neoclassical architect Sir John Soane in Bloomsbury, which keeps his incredible collection of drawings, paintings and antiques. Nearby is the Barbican, one of the most spectacular brutalist residential complexes built after the war. Another project that I always recommend to any architect who visits the city is the Snowdon Aviary at the London Zoo, one of the few buildings still standing by the visionary Cedric Price, and that can be seen perfectly from the canal without paying the entrance.