“By the age of 14 I had travelled the breadth of Spain from Santander to Jerez”

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our sixth guest, Tim Willcox, is a famous British journalist and Chief Presenter for BBC World News.

Willcox is probably one of the most recognisable presenters on BBC and is a regular face covering some of the major international events. He has anchored live on air include the death of Slobodan Milosevic, Kashmir earthquake, July 7 bombings, Boxing Day Tsunami and Beslan school siege. He is probably most recognisable for presenting the BBC’s live coverage from Chile during events surrounding the Copiapó mining accident and anchoring the BBC’s live daytime coverage during the early days of the Cairo January 2011 Egyptian revolution.

Willcox read Spanish at Durham University and is a passionate Hispanophile who has travelled widely in Spain and South America. He says to those who would like to learn it: «Do! Go for it. Fantastic people, food and culture!»

– How is life in the newsroom under the current global pandemic?

The BBC studios are at New Broadcasting House, Langham Place W1A 1AA (as in the hideously accurate comedy series of the same name). With 6 TV studios , 36 radio studios, 60 Edit and Graphics suites it is the largest broadcast centre in the world, and the biggest newsroom in Europe. Usually it is heaving with journalists and producers, cramming the meeting rooms, canteens and communal areas, and queueing for the big glass lifts that shoot between floors. Since lockdown the newsroom is practically empty, and run by a skeleton staff. Social distancing tape stripes the floor, and areas are blocked off as if one were working in a gigantic urban maze. Staircases are now designated Up or Down, and only one person is allowed to use the lifts. Many people are now working from home – less easy if you’re presenting TV bulletins. Everything has changed on that front as well. Presenters now do their own make-up, the studio cameras are automated, and guests are interviewed ‘down the line’ by Skype or Facetime. The brave new world.

– Most of us watched your live coverage of the rescue of the Chilean miners. How do you remember that coverage?

Vividly. Even 10 years later. And for many reasons. I wasn’t the first choice to go. I got a rushed call from my Editor while having a lunchtime swim in London. Did I speak Spanish? Could I get the next flight to Chile – another presenter had pulled out – to cover what was shaping up to be an extraordinary race against time? My producer and I landed in Santiago the next day to discover that our satellite dish and other key equipment had been diverted to Buenos Aires. So we took the connecting flight to Copiapo – with no luggage except a small camera. On board I noticed an empty seat by the Chilean Mining Minister Laurence Golborne and grabbed it. He was the man in charge of the rescue operation and was to become the most popular politician in Chile.

When we arrived at the San Jose Copper and Gold mine it was dawn in a heavy Camanchaca (freezing mist). A few tents containing some shivering relations of some of the miners were huddled near the mine’s entrance. Fires were being lit, and tea boiled. We were some of the first journalists there. Over the days and weeks we chatted and filmed – sometimes in my broken Spanish (which often caused guffaws of laughter when I used a word in Castellano that had a much saltier meaning in Chilean slang.) These families, wives and girlfriends grew to trust us, and told their remarkable stories. As did the rescue drilling teams and the politicians. There was no certainty that all the miners would survive. They and we knew that. There was constant fear that at any moment some or all of the men might die.

This huddle of tents and people grew voraciously into Camp Hope with its own canteen and school. The San Jose mine and the small town of Copiapo was to be their and our home for many weeks.

Within a fortnight the world’s media had descended. Car parks for hundreds of press mobile homes were bulldozed out of the rock. The Chilean authorities had erected large screens to show the whole rescue operation involving the tiny Fenix rescue capsule that would winch them 700 metres to safety. It started just before midnight and the most moving moment for me was watching the first man out Florencio Avalos. His young son was standing with his mother near President Pinera. As the Fenix capsule broke the surface, he wept and howled with emotion as he caught sight of his father for the first time in 69 days. Everyone cried that day – even journalists going live on air.

– Which other coverage has been important for you?

Every story has been important for numerous reasons. Rwanda for the sheer barbarity and horror of what had happened combined with the stoicism of its people. The Palestinian Intifada for the palpable rage in the West Bank and Gaza. The death of Diana for the sense of national and international shock that consumed so many millions of us at the time. Cities like Baghdad I remember for the internally bombed out buildings still standing like the cardboard tubes of used fireworks, and New York obviously for 9/11. These stories, like the Arab Spring coverage in Egypt and Libya, and the revolution in Ukraine, the tsunami in Japan and typhoons in the Philippines, plus all the hideous terror attacks around the world are also seared into my memory for the sense of physical exhaustion associated with live TV coverage. There aren’t many hotels still standing after natural disasters.

– You studied Spanish at University and became fluent. How was the learning process? Who were your Professors?

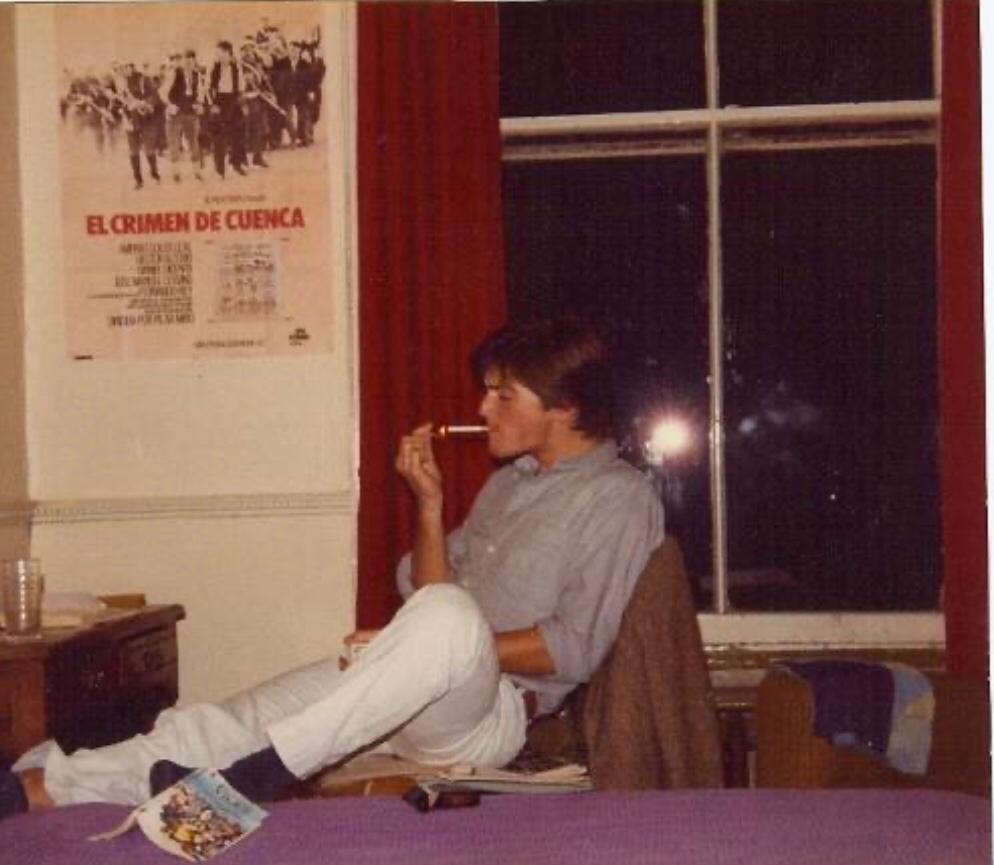

Fluent? Ojala…My love of Spain began at school and an inspirational teacher who arranged cultural / hedonistic trips. By the age of 14 I had run in the San Fermin bull festival, and travelled the breadth of Spain from Santander to Jerez. I had also listened to a lot of Albeniz, Falla and Granados. My favourite book at the time was Laurie Lee’s As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning about his journey through Spain. In my year off between school and university I retraced his journey, busking with my trumpet, and walking and hitching my way from north to south. Laurie Lee ended up near Algeciras. I completed my journey in Jerez de la Frontera where I found a temporary job as a guide at Sandeman Bodegas. At Durham university I was not a diligent student – for which I still feel shame – but I did put on productions, including Lorca’s Yerma in Spanish, and somehow get a degree. Largely thanks to the brilliant and charismatic teaching of Professor MacPherson, and Drs Dan Rodgers, Suso Ruiz and Chris Perriam who gave me a passion for Golden Age drama.

– How important is being fluent in Spanish for your journalism?

As explained it is hardly fluent. But it is useful to be able to communicate with people in their own language, and to understand their culture and national identity. It allows me to share and hopefully relate to the viewers what the characters in the story are really feeling about the events they are caught up in.

– Can you share a memory of your last news coverage in Spain?

The last story I covered in Spain was the general election. But I had been going backwards and forwards before that to Barcelona to cover the Catalan crisis. My vivid memory of that time were the huge rallies taking over the city and the drama of the declaration of independence. Sometimes we rented the large roof terrace of a stunning apartment on the Passeig de Gracia to get the best panoramic live position. Guests – both pro and anti independence were brought up to me to be interviewed. And the debates continued long after we came off air – as each side refused to change their positions.

– What would you say to someone who is thinking about learning Spanish?

Do. Go for it. Fantastic people, food and culture. And a language spoken all over the world which often opens doors. I remember meeting the Spanish Ambassador in Baghdad and after chatting away in Castellano was invited to lunch. He had the only supply of La Ina in Iraq.

– What are your favourite Spanish dishes and restaurants?

I’m basically an omnivore.

In Madrid the wonderful Ordago Restaurant near Las Ventas, also LaKasa (brilliant) and Carlos Tertiere for the best tapas and service.

In Segovia cochinillo of course at Jose Maria. Cordero asado in Pedraza always with Pedro at El Soportal.

In Barcelona – Can Colleretes. In Cadaques Compartir – for frogs legs and apple sauce. Jerez – La Tasa and Bar Juanito.

In London – it has to be Javier’s Hispania. Everything you can dream of and more….