El mejor barroco español desembarca en el prestigioso Festival de Música Barroca de Londres de la mano del CNDM y el Instituto Cervantes

Bajo el título Beyond the Spanish Golden Age (Más allá del Siglo de Oro español), cinco de las mejores agrupaciones y artistas españoles especializados en la interpretación del repertorio español antiguo y barroco desembarcarán en mayo de 2023 en el prestigioso Festival de Música Barroca de Londres, en la iglesia de St John’s Smith Square, y en el Centro Nacional para la Música Antigua de York. Estas formaciones y artistas de referencia son La Grande Chapelle (12 de mayo), Concerto 1700 (13 de mayo/ 14 de mayo en York), L’Apothéose (13 de mayo), José Miguel Moreno (14 de mayo) y Raquel Andueza y La Galanía (14 de mayo/ 13 de mayo en York).

El objetivo de este proyecto es mostrar la riqueza, la singularidad y la calidad de nuestro patrimonio musical en dos espacios internacionales de renombre que son fundamentales para la promoción de la música española; así como apoyar a los intérpretes españoles, tendiendo puentes que les permitan establecer vínculos duraderos en el tiempo con estas ambiciosas programaciones. Además, la propuesta supone una gran oportunidad para compartir fuera de nuestras fronteras la personalidad única del repertorio español y descubrir joyas musicales de la mano de algunos de nuestros mejores intérpretes especialistas en este género, tanto en su faceta instrumental como vocal.

Esta coproducción internacional se realiza en el marco del Proyecto Europa, el Programa de Internacionalización de la Música y Artes Escénicas españolas, coorganizado por el Instituto Cervantes y el Centro Nacional de Difusión Musical, INAEM, Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte de España, y el Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia — financiado por la Unión Europea— Nextgeneration.eu. Cuenta con la colaboración de la Embajada de España en Reino Unido y la colaboración de Acción Cultural Española (AC/E), en el marco de la celebración del 10º aniversario de su programa PICE para la Internacionalización de la cultura española.

Instituto Cervantes London is taking part again this year in the London Baroque Music Festival of 2023 (LFBM)

Friday 12th – Saturday 20th May 2023

St John’s Smith Square, London SW1P 3HA

Drawing from the title Kaleidoscope, the 2023 London Festival of Baroque Music (LFBM), explores the beauty of the baroque in all shapes and sizes, featuring artistic talent from Spain, France and the UK. Taking place at St John’s Smith Square from Friday 12th to Saturday 20th May 2023, the Festival will be a week of mesmerising baroque colour, largely performed in the round. The Festival includes everything from Baroque Cabaret to intimate solo performances, a harpsichord masterclass with Steven Devine to the contrasting programming of Le Concert de L’Hostel Dieu and the timbres of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment.

Highlights from Spain are presented under the programme “Beyond the Spanish Golden Age” by Instituto Cervantes; the Spanish National Centre for the Promotion of Music (CNDM); the Spanish National Institute of Performing Arts and Music (INAEM), Ministry of Culture and Sport of Spain; the Spanish Embassy in London; and funding from the European Union – Next Generation.eu.

The Festival begins with La Grande Chapelle, a vocal and instrumental group with a focus on European Early music, whose principal objective is to revive the great Spanish vocal works. This is followed by a concert from Concerto 1700; founded in 2015 by the charismatic violinist Daniel Piteño, Concerto 1700 was created with the intention of interpreting works ranging from the earliest years of the Baroque to the first glimpses of Romanticism in a historically informed manner. José Miguel Moreno, on Vihuela and Baroque Guitar, will present a programme of Spanish Guitar between 1500 and 1700. Moreno specialises in historical music interpretation, with a wide repertoire of pieces from the sixteenth century to the beginning of the twentieth century. Today, José Miguel Moreno is known as one of the greatest specialists in his field. Later in the Festival, L’Apotheose will offer a sample of both the sacred and secular music that filled the salons and ballrooms of Madrid´s Royal Court between 1720 and 1750, and Raquel Andueza and La Galanía spotlight several reconstructions of lost or forgotten typical Spanish dances and their melodies.

Exclusively for the Festival, St Johns Smith Square will host a Baroque Cabaret. The cabaret will be an exciting opportunity to hear Southbank Sinfonia chamber groups, coached by the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment in a cabaret setting, with cheese and wine served at your table for the perfect night out.

The Festival continues with the internationally renowned French-British ensemble Le Concert De L’Hostel Dieu who characterise themselves as half baroque, half contemporary. The concert fuses Baroque and Contemporary sound worlds, showcasing the freedom of Baroque music and the rich sounds of its instruments. Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment will take audiences on a musical journey through the shapes, colours, and timbres of favourite Baroque composers; delighting them with Baroque music performed by one of the top period instrument orchestras in the world. Dr John Scott Whiteley will present the organ works of J.S. Bach and his associates for a very special Lunchtime Concert.

The Festival will close with a series of Meet the Harpsichord sessions with English conductor and historical keyboard specialist, Steven Devine. On the Saturday morning, Devine will lead an open harpsichord masterclass with students from the UK’s leading conservatoires, followed by a dynamic lunchtime programme showcasing the versatility of the instrument and an enchanting opportunity to come and play the Harpsichord. With a range of historical keyboards to try, this session is the perfect chance to expand your musical knowledge.

Across ten days, this exciting Festival promises to be a rare chance to be immersed in new and familiar Baroque music.

Guildhall School y el Instituto Cervantes se vuelcan en una jornada de celebración de la música española

La Escuela Guildhall de Música y Drama de Londres acogerá una jornada de celebración de la música española este viernes, 1 de octubre, en la que el hispanista Sir Barry Ife y el Instituto Cervantes de Londres presentarán la “Sir Barry Ife – Instituto Cervantes Collection”, un fondo de libros y partituras donados a la prestigiosa escuela. Los actos estarán presididos por el nuevo Embajador de España en Londres, José Pascual Marco.

A la celebración acudirán asimismo el Director de la Escuela Guildhall de Música y Drama, el profesor Jonathan Vaughan y su Jefe de Estudios Avanzados de Interpretación en Música, el profesor Ronan O’Hora. Por parte española, y junto al Embajador, acudirán el Consejero de Asuntos Científicos y Culturales, Miguel Oliveros, y el director del Instituto Cervantes en Londres, Ignacio Peyró.

Concierto de compositoras españolas e hispanoamericanas

La jornada comenzará a las 11:00 horas con un concierto con música de compositoras históricas de España y Hispanoamérica, en cuyo programa se interpretarán piezas de Narcisa Freixas y Cruells, Alicia de Larrocha, Teresa Carreño y Tania León, entre otras. El recital tendrá lugar en la sala Court Concert Hall, del Barbican Centre, y será retransmitido en directo en el marco del Maratón Global FIMTE Almería (Festival Internacional de Música de Tecla). Los intérpretes serán alumnos de la propia Guildhall School.

Al finalizar el concierto, se podrá contemplar una muestra de la donación de partituras y libros de Sir Barry Ife y el Instituto Cervantes de Londres a la Escuela Guildhall de Música y Drama, así como el ex-libris diseñado al efecto por el tipógrafo español Alfonso Meléndez. La colección es un fondo bibliográfico compuesto por unos doscientos documentos entre libros y partituras, todos ellos con la música española como tema.

“Para nosotros’, señaló Ignacio Peyró, director del Instituto Cervantes en Londres, ‘es clave cooperar con las mejores instituciones en la difusión de nuestra cultura. Por eso colaboramos con Guildhall, que es un referente internacional y está haciendo, a la estela de Sir Barry Ife y con discípulos como Ricardo Gosalbo, un extraordinario trabajo en pro del repertorio español”. Con los fondos donados se quiere apoyar la presencia de ese repertorio y facilitar la investigación: “queremos que nuestros compositores sean interpretados”, recalcó Peyró. “Y en ningún lugar se llega como aquí a los mejores músicos del mañana, que serán los responsables de popularizarlos”.

Sir Barry Ife

El catedrático emérito Sir Barry Ife fue director de la Escuela Guildhall de Música y Drama en Londres desde septiembre de 2004 hasta enero de 2017 y actualmente es Investigador Titular de Honor de la Escuela. Leyenda del hispanismo británico, Ife está especializado en la historia cultural de España y de Hispanoamérica desde los siglos XV al XVIII. Anteriormente fue titular de la Cátedra Cervantes de Español y director en funciones del King’s College de Londres. Sus áreas de especialización son la cervantística y la música española. En los últimos años, Guildhall, Ife y el Instituto Cervantes han impulsado series de conciertos para difundir el repertorio hispánico como Highlights of Hispanic Art Song o Hispanic Music Series, que cubren cuanto va de la canción popular a Xavier Monsalvatge.

«I think what we all miss most is the very heart of what we do: trying to communicate something essential, and sharing a precious connection with an audience»

We interview tenor Nicholas Mulroy ahead of his concert Cubaroque, as part of Baroque at the Edge 2021, that invites leading musicians from all genres to take the music of the Baroque and see where it leads them.

Baroque at the Edge is not able to invite audiences to LSO St Luke’s for the 2021 festival. Instead all events will be available to buy online from now until the January release date, and subsequently available to view until 31 March 2021.

Mulroy was born in Liverpool, and has had a busy and varied career as a singer, where personal highlights have included Bach’s Matthew Passion in his own Thomaskirche, Monteverdi Vespers in Carnegie Hall, and two visits to the fantastic Australian Chamber Orchestra, as well as a broad discography including Handel, Purcell, and Piazzolla’s amazing María de Buenos Aires.

Mulroy combines singing with teaching at Goldsmiths, Cambridge, and the Royal Academy of Music, and directing. He has recently been named Associate Director of Scotland’s Dunedin Consort.

How did you become interested in becoming a tenor?

I sang as a child in Liverpool, and since then have always been involved somehow with music, whether singing or instrumental – when my voice changed I played in local youth orchestras, and had great fun in jazz and rock groups. I also sang salsa and played serenatas during my time in Ecuador, which was a lovely way of getting to know different kinds of music and performance style!

You regularly appear with leading ensembles throughout Europe, which ones do you remember as the most special ones?

I’ve had immense fortune to work with many amazing colleagues, whose inspiration and talent of course I miss at the moment. Every musician, and therefore every ensemble, has their own special energy and qualities, so it’s impossible to highlight some over others. I do, however, have fond memories of favourite concert halls: the Palau in Barcelona with its inimitable architecture; the Chagall ceiling in the Paris Opera; outdoor concerts in the Palacio Carlos V in the Alhambra. We are so fortunate as musicians to be able to work in these spaces, where the fleeting beauty of music can interact, often unforgettably, with architectural wonders.

2020 has been a difficult year to culture with the cancellation of many events and concerts, how has the covid pandemic impact your career?

I think it’s fair to say that we’re all brought low by this pandemic, and not always supported either by governments, though some artistic institutions have been superhuman. There have of course been positives: the chance to refine and reflect, and the emphasis on inner geography is a positive side-effect when it comes to thinking about creativity. On the other hand, apart from the practical implications of having concerts deleted, and income decimated, I think what we all miss most is the very heart of what we do: trying to communicate something essential, and sharing a precious connection with an audience. The fact that so little is feasible at the moment diminishes both musician and listener.

Cubaroque takes place next week. You take a new brand-new exploration from three of this country’s most distinguished baroque musicians. What does it mean to you?

The music of the Baroque has been the central element of my career until now, so singing this repertoire – Monteverdi, Purcell, Marín – is always a little like a homecoming. It’s repertoire of such expression and beauty, and its durability is testament, I think, to the way it still has huge appeal and value now. It’s a challenge and a privilege to try to make the music of the past mean something for people today.

You investigate the cultural and political background of the 1960s Latin-American and Spanish song-writing giants. How do you approach them in Cubaroque?

We wanted to shine some light on these wonderful musicians, and respond to the domination of English-speaking pop music in today’s cultural landscape. Silvio Rodríguez and Víctor Jara are figures of gigantic significance but not well-known outside the Spanish-speaking world. Both carry importance both politically and artistically in a way that is rare anywhere, and shared by only very few: one thinks of Bob Dylan or John Lennon perhaps. The way their creativity interacts with political power is something they share with Purcell and Monteverdi, both of whom were based at institutions of far-reaching influence. In one sense, we’re limited by our instrumental possibilities, so we only play acoustically, and with one voice and two guitars (or similar instruments). We have found, however, that – in spite of the historical and geographical separation – all this music shares many things: sometimes a harmonic progression or a melodic echo, often a similar feeling of confessional intimacy, and always direct, truthful responses to the possibilities that these texts and stories offer.

Getting to Know Ibero-American Classical Music: 5 Pieces to Start You Off

Pianist, Latin Classical music expert and Artistic Director of the Iberian & Latin American Music Society (ILAMS), Helen Glaisher-Hernández, recommends five pieces of Ibero-American classical music to our readers by way of introduction to this exuberant repertoire.

«I would highlight the following pieces of 20th-century repertoire which, for me, stand out for their ingenuity and originality,» says Glaisher-Hernández. The following list includes works that «conjure up imaginary musical landscapes, capable of opening doors into different, new dimensions through their ability to articulate otherworldly sounds and textures. It’s through pieces like these that we can observe Spanish and Latin American composers making genuinely original contributions to classical music that go beyond the mere ‘echoing’ of conventional European trends, as the Cuban writer, Roberto Retamar, famously put it,» adds Artistic Director of ILAMS.

- Xochipilli: An Imagined Aztec Music (1940)

Carlos Chávez (Mexico)

Carlos Chávez was known as one of the ‘Big Three’ Latin American composers of the early-to-mid 20th century, along with the Brazilian composer, Heitor Villa-Lobos, and the Argentine composer, Alberto Ginastera. The enormity of Chávez’ musical imagination and his revolutionary achievements influenced many subsequent generations of composers and changed the course of classical music-making throughout the Americas and beyond.

A child of the Mexican Revolution, Chávez became a leading feature of the so-called ‘Mexican Renaissance’ – a flowering of socialist writing, mural painting and architecture that took place in the wake of the Revolution – alongside other intellectuals and artistic figures such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. A central focus of this movement was a desire to bring the masses into the fold of the arts, in part by celebrating the indigenous oppressed, and Chávez’ music is replete with references to native Mexican music and culture.

In this vein, Chávez is best known for his Symphony No. 2 ‘Sinfonía india’, but for me it is the much more radical Xochipilli which most vividly invokes the Mexican Indian, in the form of the eponymous Aztec god of flowers, music and dance. Composed in 1940 for winds and percussion, the work was commissioned by Rockefeller for a MoMA exhibition in New York titled Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art. Chávez designed the piece so as to didactically showcase the Aztec instruments he was actively researching, but in doing so he also produced a radical and compelling piece of art, and a tour de force for any percussion section, requiring all sorts of weird and wonderful indigenous Mexican instruments. I programmed this piece at the Southbank Centre in 2012 as part of a ‘Revolutionary Concert’ celebrating the collective Latin American bicentenaries of independence, and I remember spending an inordinate amount of time trying to track down ‘hawksbells’, amongst other things.

Anyone listening to this piece who has ever visited Mexico’s pyramids and archaeological sites (and even those who haven’t) will find themselves plunged into the pre-Hispanic world in a very compelling way. A work of tremendous power, to hear it performed live feels like coming face to face with the might of the entire Aztec empire – especially as the piece gradually moves towards the formidable climax of its final movement. Chávez appears to achieve the impossible: to transport us back in time to pre-Columbian Mexico and resurrect the Aztec himself. If you can’t hear this music in concert, make sure you have the volume on your stereo speakers at home cranked up to the maximum!

A wonderfully off-the-wall, funky and fun piece, Xochipilli belies so much of Chavez’ other characteristically astringent music, which is well-known for being difficult to listen to. In contrast, I celebrate this work as an example of how, for those with less adventurous tastes at least, atonal and polytonal music can be just as beautiful and exciting as any other.

For listening, I recommend the version by Mexico’s Tambuco Percussion Ensemble performing with La Camerata on the 1994 album, ‘Carlos Chávez’.

2. Motet em ré menor ‘Beba Coca-Cola’ (1967)

Gilberto Mendes (Brazil)

This is another piece I programmed for my ‘Revolutionary Concert’ at the Southbank Centre in 2012. Out of a later period of left-wing politics, from 60s Brazil, emerged a work that speaks to Latin American anxieties over the rising dominance of American economic imperialism, offering a caustic musical indictment of the ‘contamination’ of Brazilian society by the unchecked importation of American cultural values. The Motet in D Minor, also known by the sobriquet ‘Beba Coca-Cola’ (‘Drink Coca-Cola’), is a work for mixed choir by the Brazilian composer Gilberto Mendes, based on the homonymous 1958 text by the Brazilian poet Décio Pignatari. And it is, in my opinion, nothing less than a Postmodern masterpiece.

Writing in the verbivocovisual ‘Concrete Poetry’ tradition, Pignatari plays on the marketing jingle of the multinational soft drinks company – Coca-Cola being one of the most recognisable symbols of capitalism worldwide, and advertising being part of capitalism’s essential, nefarious machinery – in order to attack the ‘system’ from within in true Postmodern fashion (instead of from the outside). The slogan-subject, ‘Beba Coca-Cola’, is turned in on itself in an act of metaphorical autosarcophagy that evokes Karl Marx’s assertion that ‘capitalism tends to destroy its [own] two sources of wealth: nature and human beings’. In both the poem and the musical work, the syllables of this sound bite are perpetually scrambled and re-scrambled in a musical gesture of anti-propaganda, the words ingeniously twisted in all directions to proffer various sorts of mischievous and derogatory semantics. ‘Babe cola’, for example (in Portuguese) alludes to the ‘drooling’ of coke, whilst ‘caco’ implies the imbibing of broken glass.

This babble provides an inexorable ostinato chant throughout the piece; a parody of the relentless subliminal message of the sales pitch. (It reminds me, more specifically, of a more recent Christmastime UK Coca-Cola ad – you know: the one where they sing ‘Holidays are coming… Holidays are coming…’). In counterpoint with this ‘mantra’, the composer scores a succession of onomatopoeic tricks, employing extended techniques such as spoken vocal lines, glissandos and breathy effects to mimic sounds such as the opening of the bottle and the escaping gas, the intoxicating effect of the bubbles. Use of microtonality incites a feeling of nausea, whilst menacing, almost gothic, dissonant intervals threaten the approach of very real malady. Eventually this bilious prattle finds relief in the form of a glorious belch by a male soloist. (I should add that this is by no means easy to pull off in the context of a live performance, as I found out with my own singers. I would strongly recommend that any choral directors attempting this piece have a burp machine on standby!)

The piece resumes only to descend into anxious cacophony, as the chant builds into an aggressive protest. If by now the listener hasn’t already got the message, the ending punch line makes the moral of the piece crystal clear, with a final re-fashioning of the slogan into a new, unequivocal word: ‘cloaca’ (‘sewer’, or ‘cesspool’). The deconstruction of the jingle is thus complete; capitalism is exposed as poisonous filth. Through ample use of the delights of the Postmodern toolkit (satire, sarcasm, repetition, intertextuality and self-consciousness), Mendes achieves a persuasive repudiation of the act of unbridled consumption itself.

The response of Coca-Cola to the premiering of this piece provides a perfect coda to the story of its composition. In lieu of the reprisals Mendes had anticipated, Coca-Cola instead sent one of their representatives to deliver a box of soft drinks to him in person, by way of thanks for ‘advertising’ the brand. ‘Speak good or bad, but talk about me,’ was the representative’s rationale. It brings to mind an aphorism often attributed to Lenin: ‘The last capitalist we hang shall be the one who sold us the rope.’

As far as I’m aware, there are no commercial recordings of this piece, or at least none that are readily available. Don’t ask me why, although given the work’s politics this seems somehow appropriate. Luckily, however, there is a nicely-filmed video clip on Youtube, featuring a performance by the OSESP Choir, excerpted from the documentary, ‘A odisseia musical de Gilberto Mendes’. What’s also nice is that you get to see a shot of the composer at the end.

3. String Quartet No. 2 ‘Reflejos de la noche’ (1984)

Mario Lavista (Mexico)

I first encountered this piece at a concert of Latin American music I attended at St John’s Smith Square many years ago featuring the Brodsky Quartet. It remains etched in my memory as one of the most incredible concerts I’ve ever attended, and the highlight was undoubtedly this piece.

Reflejos de la noche (Reflections of the Night), like Mendes’ Motet in D Minor, is another ‘festival’ of extended techniques and special timbric effects by contemporary Mexican composer, Mario Lavista. The composer’s assertion that ‘few instrumental genres have awoken the most intimate and refined imagination from composers as the string quartet’ is attested by the fact that this remains one of his most frequently performed works. In fact, following on from a long tradition of string quartet writing in Mexico, Lavista went on to write six string quartets in total, the majority of which were inspired by his acquaintance with the ensemble now widely-considered Mexico’s leading string quartet, the Cuarteto Latinoamericano.

In the score, Lavista offers some orientation in the form of a 1926 poem by the Mexican poet, Xavier Villarrutia, called Eco:

La noche juega con sus ruidos / The night plays with the noises

copiándose en sus espejos / copying them in its mirrors

de sonidos / of sounds

The work as a whole conveys a random, improvisatory feel that draws on the composer’s strong aleatory background. It is held together by a perpetual spring of gently imbricated harmonics, the ‘reflejos’ of the piece, which aimlessly float around the air like mosquitoes on a humid night. In Lavista’s own words, ‘using harmonics is, in some way, to work with reflected sounds; each one of them is produced, or generated by a fundamental sound that we never get to hear; we only perceive its harmonics, its sound-reflection.’ This gives the music an ethereal atmosphere not dissimilar to the whimsical, high-pitched interludes in the second movement of Ravel’s String Quartet in F Major. (After hearing Lavista’s piece, it may not surprise you to know that Lavista also wrote a work for oboe and eight wine-glasses!)

Other subtle textures are layered over each other – glissandi, trills and ricochet bowing help to bring all sorts of images to mind; the night sky, complete with the darting of shooting stars. The Mexicanist in me also hears the nocturnal hum of chirping crickets, and coyotes howling distantly in the background.

The repetitious and amorphous nature of the work leaves very little room for extended commentary, but that’s not to detract from its beauty; on the contrary, the work’s strength lies in the mesmeric sense of stasis that Lavista is able to sustain throughout the piece. …And so in the end, the piece doesn’t really, well…end; it just slowly and gently evaporates into the night…

The definitive version of this piece to listen to, historically speaking, is naturally the 2001 world premiere recording by the Cuarteto Latinoamericano, ‘Latin American String Quartets’ (but for sentimental reasons I also like to listen to the Brodsky’s version on their album, ‘Rhythm and Texture’).

4. Paisajes: ‘El lago’ (1947)

Frederic Mompou (Spain)

In some ways this piece is not very far removed from the contemporary Impressionism of Mario Lavista’s Reflejos de la noche, but if tonality is more your thing, you can’t fail to love this sublime miniature, ‘El lago’, by the Catalan composer, Frederic Mompou. I first encountered the music of Mompou when I was studying at Trinity College of Music in London with Elena Riu – a leading exponent of his music with whom I worked on several of his pieces.

I should start with the caveat that any pretensions to crystallise Mompou’s art in words are, in a sense, self-invalidating, since Mompou’s music is ultimately an expression of the ineffable and the esoteric; the privileging of the poetic over the prosaic. Or, as Schwerké more eloquently put it, ‘there is no exegetical system or method of chemical analysis nice enough to discover his secret.’

Mompou was really a magician in the guise of a composer; music his unique brand of transcendental magic. His first-ever composition, Cants magics (Magic Spells) is oneI’ve delighted in performing many times. But his interest in subjects such as magic, witchcraft, and even shamanism, are indicative of a more profound concern with spirituality more broadly. Mompou’s approach to composition was heavily informed by the mysticism of the Spanish Golden Age, the writings of St John of the Cross prompting pieces such as Cantar del alma and his Música callada (Silent Music), the work which best encapsulates his musical philosophy and which has been described as his magnum opus.

…That is, if ‘magnum’ is indeed a word we can apply to this music; Mompou prefers the small in scale, the intimate performance space, and the sparsely-notated score. He weaved a personal style of minimalism that allowed him to achieve maximum expression within the minimum possible means, and revelled in subtracting as many ‘unnecessary’ notes from the final work as possible. ‘I don’t compose music; I de-compose it’, he once said. These qualities, paired with a longing to rediscover the lost sensibilities of childhood, its joy and naivety, convey a kind of primitivism that led Wilfrid Mellers to describe Mompou’s music as a return to Paradise after the Fall. Whilst Stephen Hough refutes the notion that Mompou deserves a place in the hall of the ‘great’ composers, I would venture that he is, in fact, perhaps the greatest of all composers, for, free from the vanities of self-awareness, such as pretense and affectation, his music seems to touch the very forces of Creation itself.

Mompou stands apart from all his Spanish (and indeed non-Spanish) musical contemporaries; the ultimate iconoclast. ‘Quite simply put, Mompou is Mompou – there is no other music quite like his,’ say Rawlins/Hernández-Banuchi. An infamous introvert, he eschewed all ‘isms’, fads and fashions in favour of finding an independent, uncompromisingly personal voice and language. As such, he succeeded where most 20th-century composers failed: to discover an entirely fresh, tonal currency of exquisite and provocative harmonies without ever lapsing into even the slightest suggestion of kitsch or sentimentality. With the art of an alchemist, he turned dissonance into euphony.

There are traces of French influences (Mompou lived and studied in France for 30 years), but Mompou is certainly no mere ‘Spanish Debussy’ or ‘Spanish Satie’ – although his music is profoundly Spanish. There are brief, ubiquitous echoes of Catalan folk tunes, and a proliferation of the bright, metallic sonorities of local church bells. (It is no coincidence that Mompou’s grandfather owned a bell-foundry). But more fundamentally, there is a kind of dark side to his music that only Spanish artists are capable of.

‘El lago’ (‘Lake’) from Paisajes (Landscapes)is my absolute favourite of Mompou’s works. More than an archetypally pastoral image that the piece’s title might suggest, or the cascading fountains of Barcelona’s Montjuic Park that inspired it, the piece really reminds me, in a very personal way, of my experience of standing before the natural subterranean pool at the otherworldly concatenation of volcanic caves in Lanzarote known as Los Jameos del Agua. The eerie stillness of the cavern is evoked in repeated, undulating pianissimo chords, lending a hypnotic timelessness to the opening section of the piece that lulls you into a (false) sense of forgetful oblivion.

This is interrupted by the micro-dramas of a more disturbing middle section where Mompou reveals his fiery Spanish side with waves of cascading arpeggios. Mompou’s understanding of the piano’s resources allow him to showcase the sparkle of the instrument’s top register, contrasted sharply with its deep, resonating bass. Interspersed are dramatic shimmery tremolo passages that recall the swarming apian trills of Falla’s ‘Danza ritual del fuego’ (‘Ritual Fire Dance’), which are followed by slow, deep, pondering monophonic passages that provide added layers of enigma and obscurity. What’s satisfying is hearing the pauses between the phrases; contemplating the beauty of the decaying sound, reverberating as if in an echo chamber.

In the final section, disquiet gives way to tranquillity as the piece reprises its original idea. This is typical of Mompou: tension, if not resolved, is, at least, gently dissipated. All emotions – both positive and negative – are embraced and co-exist on equal terms, expressed spontaneously, moment-to-moment, rather than as part of a grand scheme, so that any sense of angst is fleeting and soon forgotten. Part of Mompou’s genius lies in this ability to conjure up several conflicting emotions, not only within the same piece, but at the same time – an impressive feat made all the more awesome given the brutal economy of his means. Perhaps that’s why the atmosphere of this piece is so difficult to put your finger on: the slow sections are melancholic in a detached, accepting kind of way, like the vague memory of a trauma long overcome. But paradoxically, there is also contentment, mystery and even danger, alongside other sensations more difficult to grasp. Both disturbing and reassuring at once, the music would seem to provide an emollient antidote to its own discomfort, thus offering a ‘therapeutic’ kind of listening experience in which pain is transcended through its own validation. Indeed, I highly recommend listening to Mompou if you are feeling in need of some emotional healing. It’s like balm to the soul.

The bad news is that although there are many available recordings of this piece, most are, quite frankly, massacres of Mompou’s music. Ironically, despite (and perhaps because of) the apparent simplicity of Mompou’s writing, his music demands a pianist of an equal capacity for nuance and understatement as its author, and ‘El lago’ especially is a piece to really sort the wheat from the chaff. Stephen Hough puts it slightly differently: ‘There is nowhere for the sophisticate to hide with Mompou. We are in a glasshouse, and the resulting transparency is unnerving, for it creates a reflection in which our face and soul can be seen.’

The good news is that amongst the wheat we can count on the sublime Arcadi Volodos, whose version on the album, ‘Volodos Plays Mompou,’ remains, for me, unmatched, and untouchable. I would even go far as to say that it surpasses the composer’s own recorded performances. Volodos is able to really maximise the music’s possibilities and make it speak. His extraordinary ability to sound-paint yields levels of pianissimo you never knew existed. Crucially, he also has an intelligent grasp of timing and an audacious and dynamic talent for rubato, always sensitive to the unfolding writing, and with an expansiveness in all the right places that heightens the music’s mystique.

Mompou was also a celebrated concert pianist before he started composing, and there is a vintage recording of him performing his entire piano catalogue that is also worth checking out: ‘Mompou: Complete Piano Works’. My only reservation with this album in the strange reverb in the production – I can’t decide if it adds to the effect of the music, or just makes it sound distorted.

5. Tango Suite (1984)

Astor Piazzolla (Argentina)

Last, but by no means least, I could hardly miss out Astor Piazzolla – not only because, in our time, this Latin American composer has now overtaken all others as the most famous and most popular internationally – but also because Piazzolla is where my passion for Latin Classical truly began.

Growing up learning the piano, I was naturally familiar with famous names like Falla, Albéniz and Villa-Lobos, as canonised by the ABRSM. A musicologist in the Canary Islands also introduced me to the vibrant piano music of Ernesto Lecuona, who remains one of my favourite composers. But it wasn’t until my year abroad in Buenos Aires that I began to realise the enormity of this ‘Latin Classical’ phenomenon, and it was Piazzolla who opened the door. I went to a lot of concerts with friends from my year group at the conservatoire, and Piazzolla seemed to be everywhere. One event that sticks in my memory is an anniversary concert we attended at the Teatro Colón (that year, 2002, marking ten years since the composer’s death). After that, I was completely hooked.

I think the Tango Suite for two guitars is probably the first piece by Piazzolla that I listened to. It’s worth noting that Piazzolla’s music covers the whole spectrum of music from the extremes of classical to popular, and everything in between (which often makes it difficult to categorise). Ironically, in classical circles Piazzolla is often better known for his more popular output, his classical works being performed only very rarely. These are what Allison Brewster Franzetti has characterised collectively as ‘the unknown Piazzolla’. This is a shame because this is where some of Piazzolla’s most interesting music is to be found. If you’d like to explore Piazzolla’s more classical side, the Tango Suite is a great place to start.

The Tango Suite was commissioned by the formidable Brazilian classical guitar duo, the Assad Brothers, who premiered it in Paris in 1984. The work broke new ground within the guitar duo repertoire, employing a dazzling array of resources, including numerous extended techniques and percussive effects.

Written in three movements, the work opens with echoes of Piazzolla’s evergreen Histoire du tango, but soon reveals itself as a relatively more complex, mature and ‘contemporary’ piece – that is, without ever descending into pure academicism. Indeed, one of the delights of this work for me is the way in which Piazzolla seems able to seamlessly syncretise popular material with more experimental methods; his talent for naturalistically reconciling the topical with the abstract. Even in Piazzolla’s more classical works, however, the tango is never far away (albeit more, or less, sublimated) and in this piece we can also hear tango rubbing shoulders with some of Piazzolla’s other major influences: jazz, Bach, Ginastera and even Stravinsky. The result is an ‘urban’ species of ‘classical cool’ which simultaneously challenges its performers to demonstrate their grasp of the ‘swing’ of the tango whilst also having to negotiate the exacting demands of the most difficult of classical guitar techniques. I think this urban cosmopolitanism is one of the reasons why Piazzolla has found particular favour today amongst slighter younger audiences.

The slower, second movement is very lyrical, conveying the more languid, sultry side of the tango, and this offers some brief respite before the piece launches into the exhilarating, relentless drive of the final movement. Here, Piazzolla lets his imagination really run wild, lurching capriciously between ideas, moving restlessly between unexpected harmonies. A (slightly) more contemplative middle section cedes to the finale: an unstoppable rollercoaster ride of further adventures through precarious harmonic and rhythmic turns. This final movement in particular interweaves a pleasing dichotomy of melody and rhythm that is particular only to Piazzolla.

There aren’t many recordings of ‘Tango Suite’ out there – I suspect for the same reason that there are so few live peformances – because, technically speaking, it’s at the harder end of the guitar repertoire. The best version I’ve come across to date is the 1998 recording by Argentine guitarists Walter Ujaldón and Marcela Sfriso. Ujaldón was on the guitar staff at the Conservatorio Nacional Superior when I was there in 2002 and I had the pleasure of hearing him perform it with Sfriso in concert. Unfortunately, their album, titled ‘Solos y duos: Piazzolla, Britten, Bach, Ginastera, Kleynjans’, has long been deleted and is difficult to get hold of these days, but I have seen second-hand copies advertised for sale on the internet, so it’s worth doing a search.

In addition, the key version to listen to is the world-premiere recording, ‘Latin American Music for Two Guitars,’ by the Assad Brothers, for whom the piece was written. The Assads are undoubtedly brilliant in everything they do, but for me this interpretation lacks the more authentic, slower tempo and Argentinian rubato of Ujaldón/Sfriso in favour of a more typically frenetic Brazilian attack. In this, the piece loses some of the sensuality and pathos that lends it greater ‘tangitude’ and local meaning.

«My experience in Argentina was life-changing and proved decisive in setting me on a career path in music»

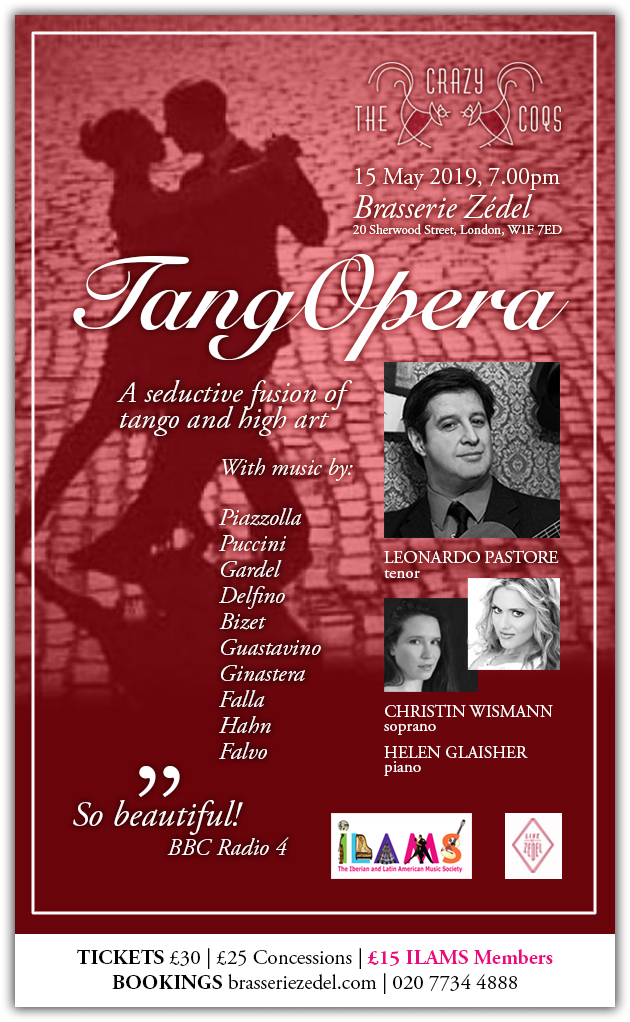

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our eighth guest, Helen Glaisher-Hernández, pianist, Latin Classical music expert and artistic director of the Iberian & Latin American Music Society (ILAMS).

For the past four years, ILAMS and Instituto Cervantes London have co-produced the ECHOES Festival of Latin Classical Music, taking place across some of the capital’s most prestigious classical music venues, such as St Martin-in-the-Fields, the Royal Academy of Music and St James’s Piccadilly.

Following two degrees in Spanish and French at the University of Cambridge (Corpus Christi College), including a year abroad studying Piano at the Conservatorio Nacional Superior in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and an MMus in Piano at Trinity College of Music in London, Glaisher-Hernández now combines her two great loves – music and hispanicity – as a concert pianist, event producer and educator specialising in Luso-Hispanic repertoire.

You often say that your two great loves are music and hispanicity. How do you combine both in your life?

Well, I was born in the UK, in Sheffield, but am also half-Spanish by virtue of my Canarian mother, who is a tinerfeña. As a child, I was quite wilful and typically replied in English whenever my mother spoke to me in Spanish. I understood her perfectly well, though, because she had persevered in speaking her mother tongue to me regardless ever since I was born. (Now my Spanish is near-native, and I feel very grateful that she did!) I perfected my Spanish at secondary school and since this was my absolute favourite A-Level subject, I then opted to read Spanish (and French) at university.

Having also studied piano from the age of four, and achieving an advanced level in my teens, it occurred to me that I could use the requisite ‘Year Abroad’ of my Languages degree to further my playing by studying piano in a Hispanic country. I’d been to Spain so many times by that point, and having never left Europe, South America beckoned to me in a much more enticing way. After investigating the options, I discovered that Argentina housed one of the best musical institutions on the continent, the Conservatorio Nacional Superior ‘López Buchardo’ in Buenos Aires, and the Dean there kindly agreed to let me enrol on the first year of their undergraduate Music degree. My experience there was life-changing and proved decisive in setting me on a career path in music – something I’d never seriously considered until then.

When I returned to England I made plans to audition for music college here after my graduation from university, and was accepted at Trinity College of Music (as it was then known); I wanted to study with a particular tutor there, the Venezuelan pianist, Elena Riu. From the off I played a lot of Luso/Hispanic music with a view to specialising in that repertoire professionally.

…And ten years later that’s essentially what I’m still doing. Of course, I play all sorts of composers (I’m not a Latin ‘fetishist’, as some people seem to think) but with my particular background, and after so many years of studying Hispanic ‘letters’ (including Hispanic literature, film, theatre and visual arts) at university, it gives me a lot of satisfaction to bring my cultural knowledge and experience to performing and promoting this wonderful but highly-neglected music; music which I sincerely believe can count itself amongst the finest ever written anywhere. In fact, I would argue that no non-native musician can authoritatively tackle this repertoire without having enjoyed a considerable level of immersion in the vast, diverse and extremely rich culture that is Hispanic culture. And I would cite cultural understanding (or a lack of it) as the main challenge facing international promoters of Latin classical music today.

Since graduating from Trinity, I feel privileged to have performed at some of the UK’s most prestigious venues, and to have been able to collaborate with some truly great artists from the Latin classical music field. At the moment I’m working on the release of my first album, which explores the globalisation of the tango through its operatic roots. The recording also features the Argentine tenor, Leonardo Pastore, soprano, Jaquelina Livieri, and mezzo-soprano, Florencia Machado – all leading opera singers in Argentina, alongside various instrumentalists from the Buenos Aires Philharmonic. Don’t ask me exactly when it’s coming out, because the Coronavirus pandemic has thrown uncertainty on all our plans, but watch this space!

Since you have a degree in Spanish and French from Cambridge University, did languages open doors to you?

So (without wishing to brag!), I actually have two degrees from Cambridge: an MA in ‘Modern and Medieval Languages’ and an MPhil in ‘European Literature’, which I decided to ‘tag on’ to my first degree before switching to Music. I did this for the entirely flippant reason that all my friends were doing it, and I thought it would be ‘fun’ to continue to maintain some sort of academic activity whilst I took a year to prepare for Music auditions. Of course, as it turned out, the MPhil was very intense and necessarily absorbed most of my time and headspace, and I ended up delaying my musical plans for another year. My MPhil, however, unexpectedly turned out to be one of the best things I’ve ever done. After four years of achieving only average-to-good marks as an undergraduate, I seemed to blossom as a postgraduate, to the extent that the Faculty subsequently offered me funding to stay on for PhD. …But I’d been too seduced by music by that point to abandon my plans. Nonetheless, I now see that year as an essential part of my education, and I particularly enjoyed working on areas such as Argentine film and the plays of Lope de Vega, whilst for my dissertation I explored the Canarian cross-currents present in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. During this year I also studied a considerable amount of Postcolonial Theory, which continues to colour my understanding of the world, and its music, to this day.

As for the opening of doors, I never really contemplated pursuing a career in Languages in the literal sense – the idea of becoming an interpreter, for example, never appealed to me, although I think it almost goes without saying that having Languages can only improve one’s career prospects in any sector. For me, the importance of Languages is not so much utilitarian as humanistic – and increasingly so in these troubled times in which we live. We Brits are infamous throughout the world for our relative reluctance to learn languages, our misplaced indolence predicated on the convenient reality that the rest of the world is more than adept at speaking ours. But instead of bringing increased peace and enlightenment, the new digital century has delivered an overwhelming intensification of globalisation that we are struggling to assimilate, and which has instead only led to culture wars, the hardening of politics and the polarisation of societies worldwide.

The mainstream media have driven public discourse into a narrow dialectic by overwhelmingly tackling these problems as political ones, but in my opinion our problems are fundamentally cultural; the result of a naive and incoherent identity politics (on all sides) spouted by people unversed in any kind of nuanced cultural thinking. A consensus of the population seem to view investment in the cultural industries as a merely optional adjunct to the ‘utilities’ of the economy, but as Winston Churchill eloquently warned us, “Ill fares the race which fails to salute the arts with the reverence and delight which are their due.” I believe that culture is the answer to all our social and political problems. In order to solve the challenges of globalism we must do better at understanding each other – the survival of the planet and our species depend on it. I consider language to be the keystone of any culture, and so in that sense, we must all learn languages. …And by the way, music is also a kind of language!

Your year abroad studying piano at the Conservatorio Nacional Superior in Buenos Aires, how was it?

If I tell you that I really didn’t want to come back at the end of the year, that might give you some sense of how devastatingly incredible it was. I went out there with consciously low expectations, never dreaming that I would literally have the time of my life. I’ve been back to Argentina many times since then, so it seems like a second home now, but I still remember how it felt that first time, and it makes me a little nostalgic to think about it. It was a very special experience that had a profound and lasting effect on my life in many ways.

I think the first time you leave Europe – as a European, I mean – it’s always something of an experience, like landing on a different planet. Argentina is a place where crazy things happen to you. Having said that, I soon felt like I strangely belonged there. Argentinian people are incredible characters, and I was quickly seduced onto their wavelength. To an extent, Argentines have a reputation for being corrupt and duplicitous, but that wasn’t my experience at all, at least not in my personal relationships. On the contrary, I think Argentines are quite simply the best people on the planet – the most generous, witty, intellectual and genuine you’ll ever encounter. Everything runs deep. When they say something, they mean it, and they’re all philosophers, down to the taxi drivers and the person checking out your shopping at the supermarket. They blew my mind constantly; every conversation was a revelation. Once they befriend you, the bond is permanent. I still have a lot of the same friends I made there 17 years ago, and they’re some of the best friends I ever had.

The city, by extension, and despite its size, is also warm and welcoming – it embraces you as you walk down the street. I lived in a student residence with Argentinians from all corners of the country who had also come to study in the capital, as well as a few Brazilians. Supposedly, the building – a traditional 19th-centuy house in the Barrio Norte district – had originally been a brothel, and it was definitely haunted – I had some unusual experiences there! There was never a dull moment.

At the time of my arrival in 2002, Argentina had just been plunged into an economic crisis and the peso had lost more than two thirds of its value overnight. Argentinians suffered terribly, but for me this was effectively like winning the lottery. It meant that me and my pounds sterling could jet-set around the country taking 5-star mini-breaks, and eat out every day of the week. I didn’t have a care in the world. It was nice to temporarily feel the liberating effects of relative wealth, although thinking about it now, it does seem a little decadent given what was going on around me.

Studying at a conservatoire for the very first time was also an awe-inspiring experience. …Bearing in mind that I was probably the first Briton to ever study there in the history of the institution. My fellow students couldn’t quite understand why on earth I would leave England to go there. I was something of a curiosity, and all the students knew who I was and wanted to be my friend. (It’s my conclusion that Argentines have a profound admiration for the British. Although they often pretend to hate us, I think they’d secretly like to be us.) I had a wonderful piano teacher, Graciela Beretervide (a former student of Arrau), with whom I studied Handel, Beethoven, Chopin and Rachmaninov. She was like a mother to me, and we still keep in touch. I also attended all the first-year modules in subjects such as Critical Theory, Musical Forms, Gregorian Chant, Alexander Technique, and so on. Studying classical Music History from the point of view of the third world, for example, was very eye-opening. The best part was that, not being a permanent student, I didn’t have to actually sit any of the exams, so I just dedicated myself to taking it all in and having a great time! By night I went out to all sorts of concerts with my friends.

It was a beautiful time. I walked around in a constant state of euphoria, with a permanent smile on my face. But it was ultimately an artificial situation which inevitably had to end. Coming back to England to do my finals was, by comparison, pretty depressing. But as Eladia Blázquez said in her famous tango, ‘siempe se vuelve a Buenos Aires’. (‘You always go back to Buenos Aires’.) And so I have, several times, and I’m sure I wild find myself there again…

How did you start to appreciate the music of different cultures and traditions from an early age?

Mainly because my father was British and my mother is Spanish, and they each tended to listen to very different things. My mother liked to have Canarian folk music on in the background, and other types of Hispanic music – Mocedades, Julio Iglesias, Rocío Jurado…as well as Latin American artists such as Mercedes Sosa, Los Panchos and Los Paraguayos.

My father, being of a slightly older generation to my mother, played a lot of music from the 1940s onwards – Glen Miller and big-band swing music, George Formby, crooners like Bing Crosby, Hollywood musicals… He also liked the pop music of the 60s and 70s. In his record collection he had Shirley Bassey, The Carpenters, Burt Bacharach, ABBA, The Bee Gees, Neil Diamond, Neil Sedaka… My father was a businessman by trade, but used to organise concerts for the Variety Club to raise money for charity – he put on huge events around Yorkshire with artists such as Matt Monroe and The Nolan Sisters.

Neither of my parents ever had any kind of musical training, although they were (are) naturally very musical and respectively very decent singers (they were always singing around the house) – I always thought both of them could have been professionals. I think the point at which they intersected musically was Nat King Cole’s En español – an album which now reminds me of them and makes me very sentimental.

In terms of classical music, I was exposed to a lot of the standard orchestral repertoire at the local youth orchestra as a teenager where I played violin, alongside things I heard on Classic FM. During my Sixth Form I also did an ALCM diploma and studied a lot of the ‘Great’ composers.

My elder brother, Mik, was a professional musician, however – he was the drummer in a successful Sheffield band of the 80s and 90s called the Comsat Angels. They had some brilliant songs, the most famous probably ‘Independence Day’. When I was a teenager, Mik would ‘corrupt’ my listening habits by making me mixtapes of the Beatles, and various rock and grunge bands I’d never heard of, like Juliana Hatfield. Obviously at that time my own interests came from what was in the Top 40, i.e. Brit Pop – Pulp (also a Sheffield band) and Radiohead probably the most. Plus any number of pop artists from that time; my biggest guilty secret being Bon Jovi. (Still is.)

As a teenager I also had musical escapades in Spain each summer when my parents would send me off to Tenerife to spend the holidays at my grandparents’ house. My aunties used to take me out clubbing with their friends and we danced to a lot of salsa. A lot of the Latin pop they played on the radio also rubbed off on me. Mónica Naranjo, Juanes, Alejandro Sanz…

You could say that my musical tastes have become very eclectic, but I only really divide music into two types: good and bad. But I like to keep an open mind and am always listening to new things. I would say music is my addiction.

You have a special passion for chamber music and vocal accompaniment. How did you become interested?

I first ‘discovered’ the beautiful thing that is chamber music at the conservatoire in Argentina. We had a weekly chamber music class in which we all had to form small ensembles and perform in front of each other. There was also a strong feeling of solidarity within the class which helped to convert me. As a pianist, the concept of playing with other people was entirely new to me. The life of a pianist is a relatively solitary one, and you really need a certain ego and temperament to want to perform publicly as a soloist – a temperament I don’t really possess. I find the experience a bit like navel-gazing in public, whereas when you collaborate with others it’s a more sociable and humbling experience. …Plus you get the benefit of seeing things from different perspectives.

I didn’t really get into vocal accompaniment until I got to Trinity, when I was approached by a soprano who was into some of the same things that I was. I’d never really had any particular interest in vocal music before then – you would have literally had to drag me by the hair to see an opera. But the more I got into it, the more I began to appreciate the marvel that is the human voice and the incredible technical feats that classical singers perform. I’ve come to agree with Avro Part, who famously said that ‘the human voice is the most perfect instrument of all’. At first I didn’t quite know how to listen discerningly to a singer (most people don’t); it was something I’ve learnt to do gradually, and I’m still learning. Now I envy singers – I really wish I could do what they do. Perhaps in my next life I’ll come back as a singer…As for this one, I’m quite content to enjoy it vicariously through the various singers I work with, and I’ve been lucky to play with some really great ones.

You have performed live at major London venues, including the Southbank Centre’s Purcell Room at Queen Elizabeth Hall, Barbican’s Milton Court Concert Hall, St John’s Smith Square, St Martin-in-the-Fields. Which one is the most special for you?

All of these venues are special in their own way and I love them all, but I would actually cite one you didn’t mention: the National Gallery in London. In 2015, I curated a concert titled Music in the Time of Goya in tandem with the blockbuster exhibition, Goya: the Portraits. In addition to being able to work with the acclaimed flamenco dancer, Nina Corti, who provided some bespoke choreographies to accompany the pieces, it was quite magical to be able to play 18th-century music at the Gallery’s illustrious Barry Rooms, surrounded by masterpieces from the same period, where Myra Hess also used to present her historic lunchtime wartime concerts. It’s a beautiful thing when art forms can converge and combine to work in synergy with the surrounding space. It also makes for a more ‘total’ experience for the audience. The project has its own website where you can view video clips and images from the performance, as well as images of some of the Goya paintings featured in the exhibition: musicinthetimeofgoya.com

You also work as Artistic Director of ILAMS in promoting Iberian classical music in the UK. What events do you curate? How did you become involved?

To answer your second question first: I started volunteering for ILAMS whilst I was still a student at Trinity. I came across the Society whilst promoting a concert I was organising, and asked the committee if they would advertise the event to their members. A few representatives from the Society came along to my concert, and on seeing that I had a pretty good turn-out I guess they thought I could be of some use to the organisation. I joined the committee in 2006, and when in 2008 the then Chairman left ILAMS, I was voted in as his successor.

Since then, the Society has developed considerably in many ways, although it remains a modest, grass-roots organisation. Our activities are now basically divided into three strands: our monthly lunchtime concert series at St Martin-in-the-Fields and St James’s Piccadilly; our bi-monthly classical guitar series, Guitarrísimo, and our annual Echoes Festival.

The complete ILAMS programme archive is viewable on the Society website, and there is also a highlights page. Personal favourites for me include presenting artists and ensembles such as Celso Machado, Leo Brouwer, John Williams, Bárbara Llanes, Onix, Marcelo Bratke, Jesús León, Coro Cervantes, Cecilia Rodrigo, Thibaut García, Douglas Riva, Moreno Gistaín Duo, Aquarelle Guitar Quartet, Lena Semenova, Jacquelina Livieri, Alvaro Pierri and the Mela Guitar Quartet, amongst many others.

You also organise Echoes Festival every year. How did it start? Can you share some great moments from these years with us?

Echoes Festival was born out of a mounting practical necessity to consolidate the limited human and financial resources of the Society, since we were previously spreading ourselves across the year with a more ad hoc programme of events which were quite disparate. We also wanted a way of focusing public attention on our activities in a more concentrated and singular way, which was facilitated by putting together all of our evening events under one umbrella. Futhermore, in 2016, the year we launched the Festival, there wasn’t (and still isn’t) an annual Festival of Latin classical music in the UK, so it seemed obvious to go in this direction.

All of the programmes from the last four editions of the Festival are available to view on the Festival website. It’s difficult for me to single out any favourite concerts because we have made a concerted effort from the start to programme artists of only the highest calibre, and even within that remit I have often been surprised at the high level we have witnessed. Of course, we’re proud to have featured more widely-known artists from the Iberican classical music circuit, such as the Quiroga Quartet, the Assad Brothers, Odaline de la Martínez and La Grande Chapelle. But some of our younger or lesser-known artists have often been equally beguiling, such as Dichos Diabolos, and the Lacock Scholars. For me, it’s also so valuable to be able to hear some of the best native specialists presenting their national repertoire – such as Venezuelan pianist, Clara Rodríguez, performing the music of her compatriot Antonio Estévez, or Alessandro Santoro performing pieces by his father, Claudio Santoro, that he grew up hearing around the house. Other events have stood out for me because of the holistic experience of hearing music in more quirky and edgy venues: pianist Carla Ruaro performing Amazonian music in the dark depths of the Brunel Tunnel, the concrete floor strewn with leaves; guitarist Darío Barozzi at the historic Cinema Museum, where Charlie Chaplin grew up.

From your experience working with ILAMS and ECHOES, do you think the interest in Iberian classical music among the British public has increased?

I’d like to think that with all the energy that ILAMS has put into our work since 1997, when the Society was founded, we have obviously had a positive impact on the reception of this music. We certainly have a much larger mailing list now than when we started, and our public has grown considerably, with capacity audiences becoming more commonplace at our events. But in broader terms, the wider impact of these things is difficult to quantify. Overall, I think animosity towards this music continues to persist amongst British audiences to the extent that we are still nowhere close to achieving parity of reception with standard European repertoire, and there is therefore still a lot of work left to do.

My sense is that it still takes the really heavy guns to make a systemic difference to the landscape: it requires the superstars of classical music – the Placido Domingos and Gustavo Dudamels of the industry – to present music at major venues and to be featured in the mainsteam classical media to really create significant shifts in public tastes; sadly, the music seems unable to do this purely on its own merits. But I think it’s understandable to a point – it’s human nature to eschew the unknown (and I’m as guilty as most people in this respect). What is always encouraging, however, is that in cases where audiences have been convinced to attend an event, their response to the music is overwhelmingly positive; certainly when ILAMS presents unfamiliar music it invariably goes down very well. Once people are exposed to this repertoire they tend to like it, so the music itself is not the problem; the challenge lies in convincing people to go and hear something they’re unfamiliar with in the first place – especially if they have to part with their hard-earned cash to do so.

London hosts the fourth edition of the Latin American classical music festival ECHOES Festival

The fourth edition of the ECHOES Latin American Classical Music Festival returns to London, taking place from October 10 to November 16 in some of the most prestigious venues for classical music in the capital, such as St Martin-in-the-Fields, the Royal Academy of Music and St James’s in Piccadilly.

The ECHOES festival is organized by the Spanish-British pianist and Latin American music expert Helen Glaisher-Hernández, and is co-produced by Instituto Cervantes in London and the Iberian & Latin American Music Society (ILAMS).

“We are proud to be able to offer a platform for some of the most authentic and illustrious voices of current Latin American classical music, some of them rarely or never heard before in the United Kingdom,” explains the artistic director of the ECHOES Festival, Helen Glaisher-Hernández.

“At Instituto Cervantes in London, we have been supporting and co-producing the ECHOES festival since its inception for several reasons: the quality of the performers and the auditoriums, the variety and originality of the repertoire and the seriousness of the ensemble. It is the most useful and beautiful way to bring the best of Latin American classical music to the public in London, ”explains the director of Instituto Cervantes in London, Ignacio Peyró.

In its fourth edition, the ECHOES Festival commemorates the 400th anniversary of the birth of Mexican composer Juan García de Zéspedes (1619 – 1678), with a concert by the Lacock Scholars. It also highlights the centenary of the birth of the Brazilian composer Cláudio Santoro (1919 – 1989) with a recital and lecture by the composer’s son, Alessandro Santoro, as well as the centenarians of the Cuban composer María Álvarez Ríos and the Brazilian Hilda Pires dos Reis.

- Promotion of young talent

The ECHOES Festival is associated with King’s College University in London for the first time, to offer a new educational platform to young talent, with free master classes on October 19th. ECHOES Festival also continues the collaboration with the Royal Academy of Music to promote contemporary music and live composers on November 1st.

In addition, Ray Picot will present a new music appreciation event on October 24 entitled Ray’s Round-Up LIVE!, focusing on the music of Enrique Granados. And ECHOES Festival is also part of the Friend Month, a five-week period of events that celebrate the history, culture and contribution of the three million Spanish and Portuguese speakers in the United Kingdom.

- Language and music to learn Spanish

This year there are more ways than ever to participate in the ECHOES Festival: even babies and toddlers can enjoy a Spanish music class called Bilingual Beats on October 29th.

While amateur singers can participate in the Mexican baroque workshop, Come & Sing on November 16th. Singers who are fond of classical music, and have some previous experience of choral interpretation, can participate in this stimulating workshop in the church of St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate.

- Music and wellness

On November 14th, GéNIA, founder of the innovative Piano-Yoga method, invites you to participate in an experience that unites mind, body and spirit. As a fresh and unique response to the current ‘yoga class with live music’ fashion, the session will combine specific yoga exercises with musical performances.

- Forgotten voices

As part of a new series of events, on November 15th, there will be a sample of the forgotten voices of the Latin composers: Women: present! The public will discover the voices of female poets and musicians that span three centuries from all corners of the Latin world, including Spain, Cuba, Venezuela, Argentina, Brazil and Mexico. The event is presented by two preeminent artists specialized in this repertoire: the soprano Lorena Paz Nieto and pianist Helen Glaisher-Hernández.

Londres acoge la cuarta edición del festival de música clásica iberoamericana ECHOES FESTIVAL

Vuelve a Londres la cuarta edición del Festival de Música Clásica Iberoamericana ECHOES, que tendrá lugar del 10 octubre al 16 de noviembre en algunos de los lugares más prestigiosos para la música clásica de la capital, como St Martin-in-the-Fields, la Royal Academy of Music y St James’s Piccadilly.

El festival ECHOES está organizado por la pianista hispano-británica y experta en música iberoamericana Helen Glaisher-Hernández, y está coproducido por el Instituto Cervantes de Londres y la Iberian & Latin American Music Society (ILAMS, por sus siglas en inglés).

“Nos enorgullece poder ofrecer una plataforma para algunas de las voces más auténticas e ilustres de la música clásica iberoamericana actual, algunas de ellas rara vez o nunca antes escuchadas en el Reino Unido”, explica la directora artística del Festival ECHOES, Helen Glaisher-Hernández.

“En el Instituto Cervantes de Londres llevamos desde su comienzo apoyando y coproduciendo el festival ECHOES por varios motivos: la calidad de los intérpretes y los auditorios, la variedad y originalidad del repertorio y la seriedad del conjunto. Es la manera más útil y hermosa de acercar al público de Londres lo mejor de la música clásica iberoamericana”, explica el director del Instituto Cervantes en Londres, Ignacio Peyró.

En esta cuarta edición, el festival ECHOES conmemora el 400 aniversario del nacimiento del compositor mexicano Juan García de Zéspedes (1619 – 1678), con un concierto de los Lacock Scholars. También destaca el centenario del natalicio del compositor brasileño Cláudio Santoro (1919 – 1989) con un recital y conferencia a cargo del hijo del compositor, Alessandro Santoro, así como los centenarios de la compositora cubana María Álvarez Ríos y la brasileña Hilda Pires dos Reis.

- Promoción del talento joven

El festival ECHOES se asocia en esta nueva edición por primera vez con la universidad de King’s College en Londres para ofrecer una nueva plataforma educativa a los talentos jóvenes, con clases magistrales abiertas gratuitas el 19 de octubre. ECHOES continúa además la colaboración con la Royal Academy of Music para promover la música contemporánea y los compositores vivos el 1 de noviembre.

Además, Ray Picot presentará un nuevo evento de apreciación musical el 24 de octubre titulado Ray’s Round-Up LIVE!, centrándose en la música de Enrique Granados. Y ECHOES también forma parte del Mes Amigo, un período de cinco semanas de eventos que celebran la historia, la cultura y la contribución de los tres millones de hispanohablantes y portugueses que hay en el Reino Unido.

- Lengua y música para aprender español

Este año hay más formas que nunca de participar en el Festival Echoes: los bebés y los niños pequeños pueden disfrutar de una clase musical en español llamada Bilingual Beats el 29 de octubre.

Mientras que los cantantes aficionados pueden participar en el taller de barroco mexicano Come & Sing el 16 de noviembre. Los cantantes aficionados por la música clásica con alguna experiencia previa de interpretación coral, podrán participar en este estimulante taller en la iglesia de St Botolph-without-Bishopsgate.

- Música y bienestar

El 14 de noviembre, GéNIA, fundadora del innovador método Piano-Yoga, invita a participar en una experiencia que une mente, cuerpo y espíritu. Como una respuesta fresca y única a la moda actual de ‘clase de yoga con música en vivo’, la sesión combinará ejercicios de yoga específicos con actuaciones musicales.

- Voces olvidadas

Como parte de una nueva serie de eventos, el 15 de noviembre habrá una muestra de las voces olvidadas de las compositoras latinas: ¡Mujeres: presentes! El público descubrirá las voces de mujeres poetas y músicas que abarcan tres siglos de todos los rincones del mundo latino, incluidos España, Cuba, Venezuela, Argentina, Brasil y México, presentados por dos preeminentes artistas especializadas en este repertorio: la soprano Lorena Paz Nieto y la pianista Helen Glaisher-Hernández.

La historia oculta de ‘El Sombrero de Tres Picos’ de Manuel de Falla, al descubierto en Londres

A punto de cumplirse el centenario del estreno del ballet ‘El sombrero de tres picos’ (julio de 1919), el escritor, músico y docente Antonio Hernández Moreno presentó las investigaciones, realizadas en las dos últimas décadas, en una conferencia organizada por el Instituto Cervantes de Londres, que revelan que casi un tercio de la partitura de El sombrero de tres picos de Manuel de Falla fue compuesta y orquestada por los compositores Maurice Ravel y Ottorino Respighi.

Hernández Moreno encontró en la Houghton Library (Universidad de Harvard) una desconocida partitura manuscrita de la música completa del ballet en versión para piano bajo el título ‘Le Chapeau tricorne’. La investigación demuestra, una vez analizadas las características caligráficas y las modificaciones que sufrió la obra original que Falla compuso bajo el título de ‘El Corregidor y la molinera’, que Ravel y Respighi arreglaron, terminaron y orquestaron la obra que daría lugar a la partitura definitiva del ballet ‘El sombrero de tres picos.’

En junio de 1916, el empresario ruso Sergei Diaghilev (en agradecimiento a las ayudas recibidas por Alfonso XIII en la liberación de Nijinsky de un campo de concentración al inicio de la Guerra Mundial) acuerda en Madrid con el dramaturgo Gregorio Martínez Sierra adaptar la novela de Pedro Antonio de Alarcón ‘El sombrero de tres picos’, para la creación de un ballet español que interpretarían los Ballets Russes. Manuel de Falla fue el compositor elegido por Diaghilev.

Después de un primer intento de estrenar la obra en Roma a principios de 1917 con ‘bailaores’ españoles, y tras un grave desencuentro con Nijinsky – ya liberado y en España– para que la estrenara junto a Pastora Imperio, Diaghilev contrata finalmente al joven y brillante bailarín español Félix García, para enseñar los ritmos españoles a los miembros de la compañía y protagonizar además dicho ballet. Félix García, además de músico, era un ‘bolero’ (nombre que recibía un bailarín experto en bailes del país), y no un ‘bailaor’ flamenco de origen andaluz como se creía.

Por entonces, la compañía de los Ballets Russes se encontraba estancada en España a causa de la Guerra Mundial, así que tras actuar en Lisboa y realizar un gira por varias ciudades de España, y casi disolverse, Diaghilev consigue liberarla del bloqueo gracias una vez más a las gestiones diplomáticas de Alfonso XIII, lo que le permite a Diaghilev y su compañía viajar finalmente a Londres en agosto de 1918.

Tras una larga temporada de actuaciones en el Coliseum Theatre, la compañía pasa al Alhambra Theatre, donde Diaghilev ya tiene previsto estrenar ‘El Corregidor y la molinera’ junto a otros ballets de carácter español. Pero nuevos contratiempos y retrasos, entre ellos la terminación de la partitura definitiva del ballet por parte de Falla, provocó que Diaghilev contratara en secreto a los compositores Ravel y Respighi para que la terminaran. La sustitución de Félix y Sokolova en los papeles principales, y el ingreso del bailarín español en un sanatorio mental no impidió que el ballet, ya con el nuevo título de “El sombrero de tres picos” se estrenara ‘in extremis’ el último día de actuación. Picasso diseñó los decorados y el vestuario, realizando un dibujo a lápiz de Félix y Sokolova durante un ensayo, única imagen que se conserva hasta ahora del bailarín español.

Hernández Moreno que establece también un paralelismo entre lo sucedido a Félix García y el destino final del legendario bailarín ruso Vaslav Nijinsky. La investigación concluye además que el conocido ‘Bolero’ de Ravel fue motivado y dedicado en secreto al propio Félix.

Los resultados de esta investigación han sido publicados de forma novelada en el libro ‘Treinta castañuelas para Londres’ que saldrá a la venta en las próximas semanas.

The hidden story of ‘The three-cornered hat’ by Spanish composer Manuel de Falla

On the occasion today of the centenary of the premiere of the ballet ‘The Three-cornered Hat’ (22nd July 1919), the research, carried out in the last two decades by the Spanish writer, musician and teacher Antonio Hernández Moreno, reveals that almost a third of the ballet score by Manuel de Falla was composed and orchestrated by composers Maurice Ravel and Ottorino Respighi.

The researcher made this information public at a lecture hosted by the Instituto Cervantes in London, hosted at the Europe House. The writer found in the Houghton Library (Harvard University) an unknown manuscript score of the ballet complete music on piano version under the title ‘Le Chapeau tricorne’. The study demonstrates, once analysed the calligraphic features and modifications made on the previous work composed by Falla under the title of ‘The Governor and the miller’s wife’, that Ravel and Respighi arranged, finished and orchestrated the work that would become the final score of the ballet ‘The Three-cornered hat.’

In June 1916, the Russian impresario Sergei Diaghilev (in gratitude for the aid received by King Alfonso XIII in the release of Nijinsky from a concentration camp at the beginning of the World War) agreed in Madrid with the playwright Gregorio Martínez Sierra to adapt the famous novel by Pedro Antonio de Alarcón, into a plot for a Spanish ballet to be premiered by the Ballets Russes. Manuel de Falla was the chosen composer by Diaghilev.

After a first failure attempt to premiere the ballet in Rome at the beginning of 1917 with Spanish ‘bailaores’, and after a serious disagreement with Nijinsky – already released and in Spain- to be represented with Pastora Imperio; Diaghilev finally hires the young and brilliant Spanish dancer Félix García, to teach the Spanish rhythms to the members of the company and also play the main role of the ballet. Felix Garcia, was not only a musician but also a very gifted ‘bolero’ or ‘bolerist’ (name given to a virtuoso dancer specialised in Spanish national dances), and not an Andalusian ‘bailaor’, as it was believed until now.

At that time, the Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes was stuck in Spain because of the World War, so after a rugged performances in Lisbon and a tour through some Spanish cities, and almost become dissolved, Diaghilev managed to release it from the blockade thanks once more to the diplomatic efforts made by King Alfonso XIII, which finally allow Diaghilev and his company to travel to London in August 1918.