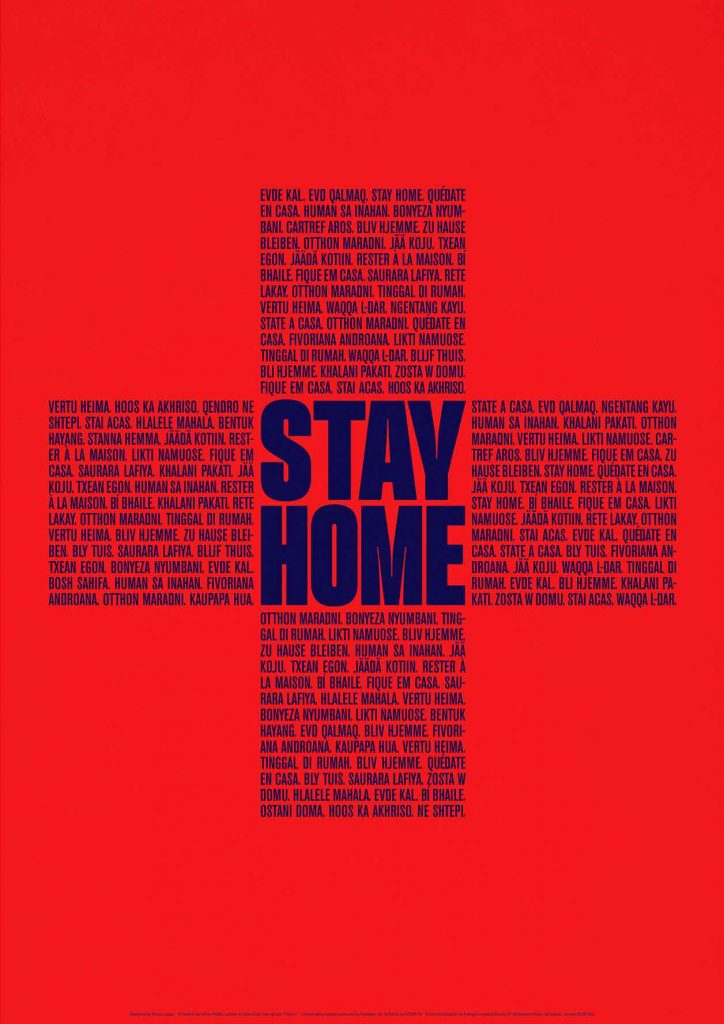

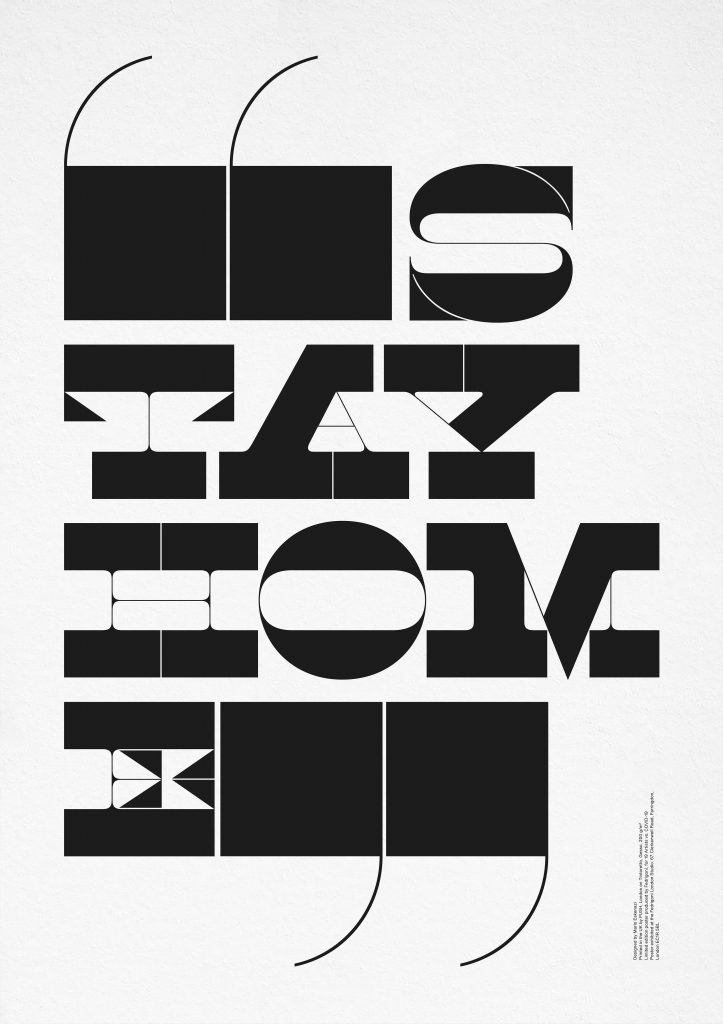

19 Artists versus COVID-19, un proyecto del diseñador gráfico español Álvaro López

19 Artists versus COVID-19 es un proyecto propuesto y organizado por el diseñador gráfico español, Álvaro López con sede en Londres, en colaboración con el fabricante de papel italiano Fedrigoni.

El proyecto trata de 19 artistas que han diseñado un póster cada uno para recaudar fondos para NHS Charities Together, una federación de 250 organizaciones benéficas que apoyan al Servicio Nacional de Salud, su personal, voluntarios y pacientes, en el Reino Unido.

El proyecto recoge a un colectivo internacional de artistas, incluyendo a Alan Kitching, Pablo Amargo, Noma Bar, Sarah Boris, Michael Curia, Nick Cook, Piero Di Biase, Mario Eskenazi, Vince Frost, Götz Gramlich, Michael Gibb, Henrik Kubel, Nina Jua Klein, Álvaro López, Rob Lowe, Morag Myerscough, Shweta Malhotra, Alejandro Paul y Matt Willey.

Se preguntó a cada artista que diseñara un póster formato A1 en torno al principal tema de actualidad que es la pandemia en la que nos encontramos envueltos. Cada uno lo interpretó de una manera muy diferente pero siempre en base al mensaje ‘Stay Home’. Este mensaje internacional ha sido muy importante en estos tiempos sin precedentes, y ha sido funda- mental para disminuir el número de afectados alrededor del mundo. Álvaro López, creador de la iniciativa y el brief dice: ‘Cada día veo en las noticias la valentía, coraje y entrega de los médicos y especialistas. Me encontaraba en casa con un ERTE y pensé que debía haber alguna manera en la que pudiera ayudar. Creo que el estar en casa, con tiempo para pensar, te hace ver las cosas desde una perspectiva muy diferente y puede llegar a ser un potente canal de inspiración. Los momentos difíciles siempre han sido una fuente de creatividad, es algo intrínseco de la naturaleza humana’

Los posters han sido producidos en litografía en la impresora del modelo Heidelberg Speedmaster por PUSH, imprenta con sede en Londres. Se ha dado la posibilidad a los artistas de usar un máximo de 4 colores pantone en una edición limitada de 75 copias por diseñador. Cada póster lleva aplicado un relieve ciego con el escudo de Fedrigoni y están numerados a mano. La elección del papel tenía que estar dentro de la gama de papeles de Fedrigoni Plus Collection.

Aunque el mensaje fuera único la manera de afrontarlo por cada diseñador fue muy diferente y enriquecedora. Algunos de ellos se dirigieron mas a la vía tipográfica como Alan Kitching, Morag Myerscough, Nick Cook, Piero Di Biase, Vince Frost, Alejandro Paul, Michael Gibb y Mario Eskenazi. También existió una corriente mas inclinada hacía la medicina y el proyecto al que se da apoyo, como Álvaro López, Götz Gramlich, Shweta Malhotra, y Noma Bar.

Y otros tendieron a una línea mas arquitectónica como Sarah Boris, Pablo Amargo, Michael Curia, Nina Jua Klein, Henrik Kubel, Matt Willey y Rob Lowe. Cada póster es único y juntos combinan una serie de emociones tan habitiuales estos días como son la soledad, el aislamiento, la frustación del distanciamiento, la falta de seguridad, pero a su vez muestran un apoyo y postivismo haciá lo que nos encontraremos en un futuro cada vez mas cercano.

Los pósters se están vendiendo en la página web www.19vs19.co.uk al precio de £19. La primera edición numerada de cada póster se subastará mas adelante. Una vez el aislamiento finalice y todo vuelva a la normalidad, los pósters se mostrarán en una exposición en la sede central de Fedrigoni en Londres.

Los 19 artistas quieren agradecer el esfuerzo a Fedrigoni UK, PUSH London, Premier Paper y UPS.

Web www.19vs19.co.uk

Instagram 19vs19 @19artistsversuscovid19

Instagram Álvaro López @alvarus85

Encuentro con Gerard Vidal, director de «Tahrib»

Rafael Cueto y Alberto M. Valverde, de cinemaattic.com, plataforma para la difusión del cortometraje en Escocia, charlan con Gerard Vidal sobre las influencias de «Tahrib» y repasan el contexto de producción del corto y su temática.

Encuentro organizado por el Instituto Cervantes de Londres en el marco de la Muestra en línea de cortometrajes iberoamericanos del Instituto Cervantes y huesca-filmfestival.com.

Hoja de sala de «Tahrib»: cvc.cervantes.es/artes/cine/hojas/tahrib.htm

Presentación de «Tahrib», a cargo de su director, Gerard Vidal:

«Spending so much of my life in Spain means I really appreciate the moment, just enjoying where I happen to be»

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our ninth guest, Annie Bennett, specialises in writing about Spain and is usually mooching around the country searching for the perfect tapas bar.

Bennett writes for The Daily and Sunday Telegraph and she is their Madrid expert. She has also contributed to The Guardian and Observer, The Times, The Financial Times, The Sunday Times Travel Magazine, The Independent and Independent on Sunday, Travel Weekly, Conde Nast Traveller, Tatler, Elle, Red, Time Out & various airline magazines.

Her latest book is Insight Explore Madrid (January 2018) and she has also written National Geographic Traveler Madrid, Blue Guide Madrid, Blue Guide Barcelona and Art Shop Eat Barcelona. She has won a few awards over the years, including Spain Travel Writer of the Year.

– You describe yourself as a food & travel writer mooching around Spain for Telegraph & other UK nationals. How did you get to this job? Why Spain?

I studied Spanish and German at the University of Westminster, specialising in translation and interpreting. As I had lived in Cologne for a couple of years before doing my degree, my German was much stronger than my Spanish, so after graduating I went to live in Madrid to try and improve it. This was the early 1980s and I was lucky enough to become friends with some of the key figures of the Movida, which opened the door to the dynamic creative scene. I became quite involved in the art world and started translating for galleries and museums. It wasn’t long before I started writing, just because I knew such interesting people really. I first interviewed Pedro Almodóvar back in 1985!

I moved back to London in 1992 for a few years, but my links with Spain became stronger than ever when I started travel writing. I wrote the Blue Guides to Madrid and Barcelona and started contributing to national newspapers and magazines. And I have just kept going with articles and books – my list of places in Spain I want to write about just gets longer and longer.

– You are based between Madrid and South Wales, is that the perfect combo?

My family is in South Wales and I do a lot of my writing here. I love the beaches of the Gower Peninsula, which are actually quite similar to those on the Rías Altas in Galicia. I’ve been here during lockdown and it is wonderful to be able to walk along the beach every day and explore Gower without tourists.

As I write about Spanish tourism for British people, it really helps to live a caballo between the two countries, to keep my finger on the pulse of what people are talking about and what they are familiar with in Spain, whether culture, gastronomy or tourism. I can’t assume that everyone knows who Velázquez or Rosalía are, for example. Now everyone buys chorizo in the supermarket and chucks it in everything (I’m not mentioning paella), but that certainly wasn’t the case 20 years ago. I’m currently reading María José Sevilla’s brilliant new book, Delicioso: The History of Food in Spain; we really needed a serious book in English about Spanish food and I’m really enjoying having the time to read it during lockdown.

– What places do you like visiting when you are in Spain? What topics do you like covering?

Madrid is home to me and I am champing at the bit to get back there. Something that has really surprised me during lockdown is how much I’m missing it and I have cried quite a few times watching videos and news reports of what is happening there.

But as 2020 is the centenary of the death of Benito Pérez Galdós, I am spending a lot of time in Madrid, albeit just in my head, by rereading Fortunata y Jacinta and his other wonderful novels. It is frustrating not to be able to take part in the walks and other events in the city organised to commemorate the anniversary, but as I know the streets and locations so well, it is almost like being there.

I love Valencia too and go a few times a year. I think it is a very underrated city, for culture and the urban beaches but more than anything the food. I could happily eat a rice dish for lunch every day. The produce there is so good and varied; I think it has one of the most dynamic gastronomic scenes in Spain, with fantastic chefs such as Ricard Camarena, Quique Dacosta and Bernd Knöller, to mention just a few. I’ve been going to Casa Montaña in the Cabanyal neighbourhood by the sea for more than two decades and it is my favourite tapas bar in Spain.

I find the area around Vejer de la Frontera on the Costa de la Luz quite intoxicating. The food scene is really interesting, there are fabulous beaches and I always seem to have a glass of sherry in my hand. One of the most exciting and memorable experiences I have ever had as a travel writer was being on one of the almadraba boats to witness the catch of bluefin tuna at close hand. I really enjoyed writing about this fascinating tradition – and eating just about every part of the tuna in the El Campero restaurant in Barbate.

I go the Hay Festival in Segovia every year, although I’m not sure if it is going to be possible this September. It is always one of the most enriching experiences of the year and listening to writers and artists talk about their work in convents, courtyards and gardens is just magical.

Lanzarote is a favourite too, although I hardly ever get to lie on a beach there. I have been writing about the ecotourism scene for the last decade or so and took part in the Saborea Lanzarote gastronomic festival last year. The cheeses and wines produced on the island are spectacular.

– How has the experience been? What do you enjoy the most about Spain?

Spending so much of my life in Spain means I really appreciate the moment, just enjoying where I happen to be. I love being in places some people consider unfashionable or not cool. I don’t care about that; in fact it’s a positive advantage to me. I’ve got a long list of towns in this category to visit or revisit when we can travel again. Getting a taste of how people just quietly go about leading very enjoyable lives without having to shout about it, in places that don’t get written about much, is one of the best things about Spain for me. I am always singing the praises of Soria and Jaén and have written several articles about the extraordinary cultural heritage of Alcalá de Henares.

– You visit places off the beaten track, could you tell us your favourite spots?

I’ve been a regular visitor to the Alpujarras for a long time, ever since I became fascinated by this magical mountain area after reading The Silence of the Sirens by Adelaida García Morales. She captured the hypnotic atmosphere of the astounding landscape so well. I was thrilled a few years ago to actually meet a curandera while walking down a track with a friend who lives there, as these local faith healers play an important part in the book.

Of course, the Alpujarras have become much more well known as so many people have read the wonderful books by Chris Stewart, since his best-selling Driving over Lemons was published two decades ago. Somewhere that still feels remote, however, is Babia, in the north-west of León. I had been reading about the area for years before I actually made it there, mostly in books and articles by Julio Llamazares and Luis Mateo Díez.

More recently, I was lucky enough to spend some time just over the border from Babia in the Somiedo area of Asturias, where brown bears prowl around the mountains. Getting up before dawn to go and spot them with local experts was a brilliant experience.

– You wrote an article with 20 reasons why British travellers will all return to Spain when this is finally over: boozy lunches, fast trains, slow trains, jamón, prawns, aperitivos, paradors, beaches… are you ready to go back?

While I am dying to return to Spain, I think I’m going to see how the situation develops as I am a bit wary about the potential health risks involved with being in airports and flying. I just want to be there without having to do the travelling really. I’m thinking it might be a good plan to enjoy the Gower beaches over the summer and start my Spain explorations again from September, although I’m not sure I’ll be able to wait that long.

– In Spain we have rural houses all around the country, have you ever stayed in one? Do you have any favourites?

As I review so many hotels, I don’t get to stay in as many rural places as I would like. I am however a big fan of rural tourism and have been writing about it for more than 20 years. There are so many extraordinary places to stay in the countryside and on lesser-known parts of the coast. I’ve stayed in some gorgeous houses and small rural hotels in Cabo de Gata in Andalucía, Cantabria, Asturias, Galicia and the Canary Islands. I stayed in an amazing house in Lanzarote that was actually a converted water cistern but looked like something from a James Bond film.

– Now it is easier to find Spanish ingredients and products in the UK. Which ones were always the hardest ones to find? Which ones are always in your larder?

I don’t actually buy that many Spanish products in the UK as I am usually – before the pandemic obviously – travelling backwards and forwards so frequently. Looking in my cupboards, I have pimentón, saffron, jars of good tuna and tins of sea urchin paté and anchovies. There is always a good supply of turrón and Paladín hot chocolate, which are my mother’s favourites. I always have quite a few olive oils from different parts of Spain as well as sherry vinegar. I seem to have got through most of my stock of Spanish wines and sherries though….

It is wonderful that now it is easy to get excellent olive oils, ham, cheeses, paella rice and wines from fantastic producers, delis and restaurants such as José Pizarro and Brindisa. Here in Wales we are lucky to have the Bar 44 and Ultracomida groups, who are absolutely passionate about Spanish produce and have been doing some great live tasting events during lockdown.

Getting to Know Ibero-American Classical Music: 5 Pieces to Start You Off

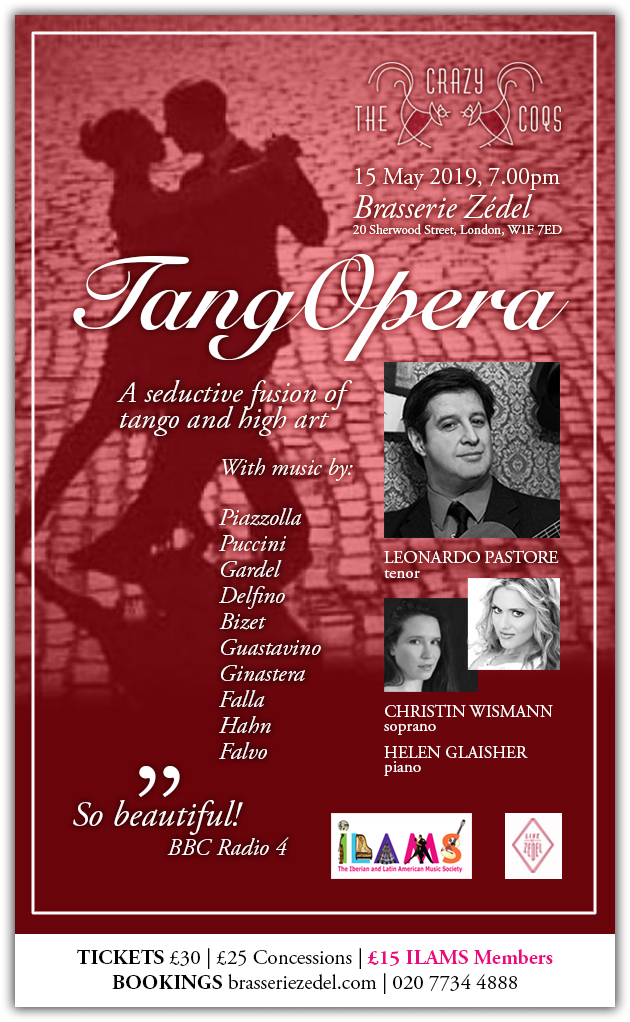

Pianist, Latin Classical music expert and Artistic Director of the Iberian & Latin American Music Society (ILAMS), Helen Glaisher-Hernández, recommends five pieces of Ibero-American classical music to our readers by way of introduction to this exuberant repertoire.

«I would highlight the following pieces of 20th-century repertoire which, for me, stand out for their ingenuity and originality,» says Glaisher-Hernández. The following list includes works that «conjure up imaginary musical landscapes, capable of opening doors into different, new dimensions through their ability to articulate otherworldly sounds and textures. It’s through pieces like these that we can observe Spanish and Latin American composers making genuinely original contributions to classical music that go beyond the mere ‘echoing’ of conventional European trends, as the Cuban writer, Roberto Retamar, famously put it,» adds Artistic Director of ILAMS.

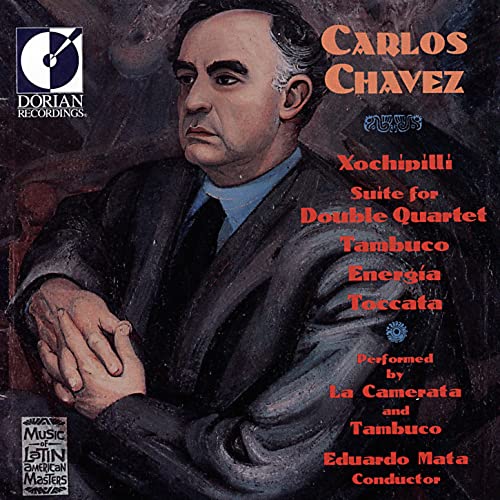

- Xochipilli: An Imagined Aztec Music (1940)

Carlos Chávez (Mexico)

Carlos Chávez was known as one of the ‘Big Three’ Latin American composers of the early-to-mid 20th century, along with the Brazilian composer, Heitor Villa-Lobos, and the Argentine composer, Alberto Ginastera. The enormity of Chávez’ musical imagination and his revolutionary achievements influenced many subsequent generations of composers and changed the course of classical music-making throughout the Americas and beyond.

A child of the Mexican Revolution, Chávez became a leading feature of the so-called ‘Mexican Renaissance’ – a flowering of socialist writing, mural painting and architecture that took place in the wake of the Revolution – alongside other intellectuals and artistic figures such as Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. A central focus of this movement was a desire to bring the masses into the fold of the arts, in part by celebrating the indigenous oppressed, and Chávez’ music is replete with references to native Mexican music and culture.

In this vein, Chávez is best known for his Symphony No. 2 ‘Sinfonía india’, but for me it is the much more radical Xochipilli which most vividly invokes the Mexican Indian, in the form of the eponymous Aztec god of flowers, music and dance. Composed in 1940 for winds and percussion, the work was commissioned by Rockefeller for a MoMA exhibition in New York titled Twenty Centuries of Mexican Art. Chávez designed the piece so as to didactically showcase the Aztec instruments he was actively researching, but in doing so he also produced a radical and compelling piece of art, and a tour de force for any percussion section, requiring all sorts of weird and wonderful indigenous Mexican instruments. I programmed this piece at the Southbank Centre in 2012 as part of a ‘Revolutionary Concert’ celebrating the collective Latin American bicentenaries of independence, and I remember spending an inordinate amount of time trying to track down ‘hawksbells’, amongst other things.

Anyone listening to this piece who has ever visited Mexico’s pyramids and archaeological sites (and even those who haven’t) will find themselves plunged into the pre-Hispanic world in a very compelling way. A work of tremendous power, to hear it performed live feels like coming face to face with the might of the entire Aztec empire – especially as the piece gradually moves towards the formidable climax of its final movement. Chávez appears to achieve the impossible: to transport us back in time to pre-Columbian Mexico and resurrect the Aztec himself. If you can’t hear this music in concert, make sure you have the volume on your stereo speakers at home cranked up to the maximum!

A wonderfully off-the-wall, funky and fun piece, Xochipilli belies so much of Chavez’ other characteristically astringent music, which is well-known for being difficult to listen to. In contrast, I celebrate this work as an example of how, for those with less adventurous tastes at least, atonal and polytonal music can be just as beautiful and exciting as any other.

For listening, I recommend the version by Mexico’s Tambuco Percussion Ensemble performing with La Camerata on the 1994 album, ‘Carlos Chávez’.

2. Motet em ré menor ‘Beba Coca-Cola’ (1967)

Gilberto Mendes (Brazil)

This is another piece I programmed for my ‘Revolutionary Concert’ at the Southbank Centre in 2012. Out of a later period of left-wing politics, from 60s Brazil, emerged a work that speaks to Latin American anxieties over the rising dominance of American economic imperialism, offering a caustic musical indictment of the ‘contamination’ of Brazilian society by the unchecked importation of American cultural values. The Motet in D Minor, also known by the sobriquet ‘Beba Coca-Cola’ (‘Drink Coca-Cola’), is a work for mixed choir by the Brazilian composer Gilberto Mendes, based on the homonymous 1958 text by the Brazilian poet Décio Pignatari. And it is, in my opinion, nothing less than a Postmodern masterpiece.

Writing in the verbivocovisual ‘Concrete Poetry’ tradition, Pignatari plays on the marketing jingle of the multinational soft drinks company – Coca-Cola being one of the most recognisable symbols of capitalism worldwide, and advertising being part of capitalism’s essential, nefarious machinery – in order to attack the ‘system’ from within in true Postmodern fashion (instead of from the outside). The slogan-subject, ‘Beba Coca-Cola’, is turned in on itself in an act of metaphorical autosarcophagy that evokes Karl Marx’s assertion that ‘capitalism tends to destroy its [own] two sources of wealth: nature and human beings’. In both the poem and the musical work, the syllables of this sound bite are perpetually scrambled and re-scrambled in a musical gesture of anti-propaganda, the words ingeniously twisted in all directions to proffer various sorts of mischievous and derogatory semantics. ‘Babe cola’, for example (in Portuguese) alludes to the ‘drooling’ of coke, whilst ‘caco’ implies the imbibing of broken glass.

This babble provides an inexorable ostinato chant throughout the piece; a parody of the relentless subliminal message of the sales pitch. (It reminds me, more specifically, of a more recent Christmastime UK Coca-Cola ad – you know: the one where they sing ‘Holidays are coming… Holidays are coming…’). In counterpoint with this ‘mantra’, the composer scores a succession of onomatopoeic tricks, employing extended techniques such as spoken vocal lines, glissandos and breathy effects to mimic sounds such as the opening of the bottle and the escaping gas, the intoxicating effect of the bubbles. Use of microtonality incites a feeling of nausea, whilst menacing, almost gothic, dissonant intervals threaten the approach of very real malady. Eventually this bilious prattle finds relief in the form of a glorious belch by a male soloist. (I should add that this is by no means easy to pull off in the context of a live performance, as I found out with my own singers. I would strongly recommend that any choral directors attempting this piece have a burp machine on standby!)

The piece resumes only to descend into anxious cacophony, as the chant builds into an aggressive protest. If by now the listener hasn’t already got the message, the ending punch line makes the moral of the piece crystal clear, with a final re-fashioning of the slogan into a new, unequivocal word: ‘cloaca’ (‘sewer’, or ‘cesspool’). The deconstruction of the jingle is thus complete; capitalism is exposed as poisonous filth. Through ample use of the delights of the Postmodern toolkit (satire, sarcasm, repetition, intertextuality and self-consciousness), Mendes achieves a persuasive repudiation of the act of unbridled consumption itself.

The response of Coca-Cola to the premiering of this piece provides a perfect coda to the story of its composition. In lieu of the reprisals Mendes had anticipated, Coca-Cola instead sent one of their representatives to deliver a box of soft drinks to him in person, by way of thanks for ‘advertising’ the brand. ‘Speak good or bad, but talk about me,’ was the representative’s rationale. It brings to mind an aphorism often attributed to Lenin: ‘The last capitalist we hang shall be the one who sold us the rope.’

As far as I’m aware, there are no commercial recordings of this piece, or at least none that are readily available. Don’t ask me why, although given the work’s politics this seems somehow appropriate. Luckily, however, there is a nicely-filmed video clip on Youtube, featuring a performance by the OSESP Choir, excerpted from the documentary, ‘A odisseia musical de Gilberto Mendes’. What’s also nice is that you get to see a shot of the composer at the end.

3. String Quartet No. 2 ‘Reflejos de la noche’ (1984)

Mario Lavista (Mexico)

I first encountered this piece at a concert of Latin American music I attended at St John’s Smith Square many years ago featuring the Brodsky Quartet. It remains etched in my memory as one of the most incredible concerts I’ve ever attended, and the highlight was undoubtedly this piece.

Reflejos de la noche (Reflections of the Night), like Mendes’ Motet in D Minor, is another ‘festival’ of extended techniques and special timbric effects by contemporary Mexican composer, Mario Lavista. The composer’s assertion that ‘few instrumental genres have awoken the most intimate and refined imagination from composers as the string quartet’ is attested by the fact that this remains one of his most frequently performed works. In fact, following on from a long tradition of string quartet writing in Mexico, Lavista went on to write six string quartets in total, the majority of which were inspired by his acquaintance with the ensemble now widely-considered Mexico’s leading string quartet, the Cuarteto Latinoamericano.

In the score, Lavista offers some orientation in the form of a 1926 poem by the Mexican poet, Xavier Villarrutia, called Eco:

La noche juega con sus ruidos / The night plays with the noises

copiándose en sus espejos / copying them in its mirrors

de sonidos / of sounds

The work as a whole conveys a random, improvisatory feel that draws on the composer’s strong aleatory background. It is held together by a perpetual spring of gently imbricated harmonics, the ‘reflejos’ of the piece, which aimlessly float around the air like mosquitoes on a humid night. In Lavista’s own words, ‘using harmonics is, in some way, to work with reflected sounds; each one of them is produced, or generated by a fundamental sound that we never get to hear; we only perceive its harmonics, its sound-reflection.’ This gives the music an ethereal atmosphere not dissimilar to the whimsical, high-pitched interludes in the second movement of Ravel’s String Quartet in F Major. (After hearing Lavista’s piece, it may not surprise you to know that Lavista also wrote a work for oboe and eight wine-glasses!)

Other subtle textures are layered over each other – glissandi, trills and ricochet bowing help to bring all sorts of images to mind; the night sky, complete with the darting of shooting stars. The Mexicanist in me also hears the nocturnal hum of chirping crickets, and coyotes howling distantly in the background.

The repetitious and amorphous nature of the work leaves very little room for extended commentary, but that’s not to detract from its beauty; on the contrary, the work’s strength lies in the mesmeric sense of stasis that Lavista is able to sustain throughout the piece. …And so in the end, the piece doesn’t really, well…end; it just slowly and gently evaporates into the night…

The definitive version of this piece to listen to, historically speaking, is naturally the 2001 world premiere recording by the Cuarteto Latinoamericano, ‘Latin American String Quartets’ (but for sentimental reasons I also like to listen to the Brodsky’s version on their album, ‘Rhythm and Texture’).

4. Paisajes: ‘El lago’ (1947)

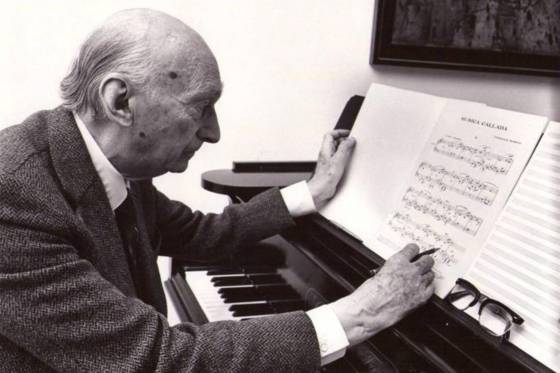

Frederic Mompou (Spain)

In some ways this piece is not very far removed from the contemporary Impressionism of Mario Lavista’s Reflejos de la noche, but if tonality is more your thing, you can’t fail to love this sublime miniature, ‘El lago’, by the Catalan composer, Frederic Mompou. I first encountered the music of Mompou when I was studying at Trinity College of Music in London with Elena Riu – a leading exponent of his music with whom I worked on several of his pieces.

I should start with the caveat that any pretensions to crystallise Mompou’s art in words are, in a sense, self-invalidating, since Mompou’s music is ultimately an expression of the ineffable and the esoteric; the privileging of the poetic over the prosaic. Or, as Schwerké more eloquently put it, ‘there is no exegetical system or method of chemical analysis nice enough to discover his secret.’

Mompou was really a magician in the guise of a composer; music his unique brand of transcendental magic. His first-ever composition, Cants magics (Magic Spells) is oneI’ve delighted in performing many times. But his interest in subjects such as magic, witchcraft, and even shamanism, are indicative of a more profound concern with spirituality more broadly. Mompou’s approach to composition was heavily informed by the mysticism of the Spanish Golden Age, the writings of St John of the Cross prompting pieces such as Cantar del alma and his Música callada (Silent Music), the work which best encapsulates his musical philosophy and which has been described as his magnum opus.

…That is, if ‘magnum’ is indeed a word we can apply to this music; Mompou prefers the small in scale, the intimate performance space, and the sparsely-notated score. He weaved a personal style of minimalism that allowed him to achieve maximum expression within the minimum possible means, and revelled in subtracting as many ‘unnecessary’ notes from the final work as possible. ‘I don’t compose music; I de-compose it’, he once said. These qualities, paired with a longing to rediscover the lost sensibilities of childhood, its joy and naivety, convey a kind of primitivism that led Wilfrid Mellers to describe Mompou’s music as a return to Paradise after the Fall. Whilst Stephen Hough refutes the notion that Mompou deserves a place in the hall of the ‘great’ composers, I would venture that he is, in fact, perhaps the greatest of all composers, for, free from the vanities of self-awareness, such as pretense and affectation, his music seems to touch the very forces of Creation itself.

Mompou stands apart from all his Spanish (and indeed non-Spanish) musical contemporaries; the ultimate iconoclast. ‘Quite simply put, Mompou is Mompou – there is no other music quite like his,’ say Rawlins/Hernández-Banuchi. An infamous introvert, he eschewed all ‘isms’, fads and fashions in favour of finding an independent, uncompromisingly personal voice and language. As such, he succeeded where most 20th-century composers failed: to discover an entirely fresh, tonal currency of exquisite and provocative harmonies without ever lapsing into even the slightest suggestion of kitsch or sentimentality. With the art of an alchemist, he turned dissonance into euphony.

There are traces of French influences (Mompou lived and studied in France for 30 years), but Mompou is certainly no mere ‘Spanish Debussy’ or ‘Spanish Satie’ – although his music is profoundly Spanish. There are brief, ubiquitous echoes of Catalan folk tunes, and a proliferation of the bright, metallic sonorities of local church bells. (It is no coincidence that Mompou’s grandfather owned a bell-foundry). But more fundamentally, there is a kind of dark side to his music that only Spanish artists are capable of.

‘El lago’ (‘Lake’) from Paisajes (Landscapes)is my absolute favourite of Mompou’s works. More than an archetypally pastoral image that the piece’s title might suggest, or the cascading fountains of Barcelona’s Montjuic Park that inspired it, the piece really reminds me, in a very personal way, of my experience of standing before the natural subterranean pool at the otherworldly concatenation of volcanic caves in Lanzarote known as Los Jameos del Agua. The eerie stillness of the cavern is evoked in repeated, undulating pianissimo chords, lending a hypnotic timelessness to the opening section of the piece that lulls you into a (false) sense of forgetful oblivion.

This is interrupted by the micro-dramas of a more disturbing middle section where Mompou reveals his fiery Spanish side with waves of cascading arpeggios. Mompou’s understanding of the piano’s resources allow him to showcase the sparkle of the instrument’s top register, contrasted sharply with its deep, resonating bass. Interspersed are dramatic shimmery tremolo passages that recall the swarming apian trills of Falla’s ‘Danza ritual del fuego’ (‘Ritual Fire Dance’), which are followed by slow, deep, pondering monophonic passages that provide added layers of enigma and obscurity. What’s satisfying is hearing the pauses between the phrases; contemplating the beauty of the decaying sound, reverberating as if in an echo chamber.

In the final section, disquiet gives way to tranquillity as the piece reprises its original idea. This is typical of Mompou: tension, if not resolved, is, at least, gently dissipated. All emotions – both positive and negative – are embraced and co-exist on equal terms, expressed spontaneously, moment-to-moment, rather than as part of a grand scheme, so that any sense of angst is fleeting and soon forgotten. Part of Mompou’s genius lies in this ability to conjure up several conflicting emotions, not only within the same piece, but at the same time – an impressive feat made all the more awesome given the brutal economy of his means. Perhaps that’s why the atmosphere of this piece is so difficult to put your finger on: the slow sections are melancholic in a detached, accepting kind of way, like the vague memory of a trauma long overcome. But paradoxically, there is also contentment, mystery and even danger, alongside other sensations more difficult to grasp. Both disturbing and reassuring at once, the music would seem to provide an emollient antidote to its own discomfort, thus offering a ‘therapeutic’ kind of listening experience in which pain is transcended through its own validation. Indeed, I highly recommend listening to Mompou if you are feeling in need of some emotional healing. It’s like balm to the soul.

The bad news is that although there are many available recordings of this piece, most are, quite frankly, massacres of Mompou’s music. Ironically, despite (and perhaps because of) the apparent simplicity of Mompou’s writing, his music demands a pianist of an equal capacity for nuance and understatement as its author, and ‘El lago’ especially is a piece to really sort the wheat from the chaff. Stephen Hough puts it slightly differently: ‘There is nowhere for the sophisticate to hide with Mompou. We are in a glasshouse, and the resulting transparency is unnerving, for it creates a reflection in which our face and soul can be seen.’

The good news is that amongst the wheat we can count on the sublime Arcadi Volodos, whose version on the album, ‘Volodos Plays Mompou,’ remains, for me, unmatched, and untouchable. I would even go far as to say that it surpasses the composer’s own recorded performances. Volodos is able to really maximise the music’s possibilities and make it speak. His extraordinary ability to sound-paint yields levels of pianissimo you never knew existed. Crucially, he also has an intelligent grasp of timing and an audacious and dynamic talent for rubato, always sensitive to the unfolding writing, and with an expansiveness in all the right places that heightens the music’s mystique.

Mompou was also a celebrated concert pianist before he started composing, and there is a vintage recording of him performing his entire piano catalogue that is also worth checking out: ‘Mompou: Complete Piano Works’. My only reservation with this album in the strange reverb in the production – I can’t decide if it adds to the effect of the music, or just makes it sound distorted.

5. Tango Suite (1984)

Astor Piazzolla (Argentina)

Last, but by no means least, I could hardly miss out Astor Piazzolla – not only because, in our time, this Latin American composer has now overtaken all others as the most famous and most popular internationally – but also because Piazzolla is where my passion for Latin Classical truly began.

Growing up learning the piano, I was naturally familiar with famous names like Falla, Albéniz and Villa-Lobos, as canonised by the ABRSM. A musicologist in the Canary Islands also introduced me to the vibrant piano music of Ernesto Lecuona, who remains one of my favourite composers. But it wasn’t until my year abroad in Buenos Aires that I began to realise the enormity of this ‘Latin Classical’ phenomenon, and it was Piazzolla who opened the door. I went to a lot of concerts with friends from my year group at the conservatoire, and Piazzolla seemed to be everywhere. One event that sticks in my memory is an anniversary concert we attended at the Teatro Colón (that year, 2002, marking ten years since the composer’s death). After that, I was completely hooked.

I think the Tango Suite for two guitars is probably the first piece by Piazzolla that I listened to. It’s worth noting that Piazzolla’s music covers the whole spectrum of music from the extremes of classical to popular, and everything in between (which often makes it difficult to categorise). Ironically, in classical circles Piazzolla is often better known for his more popular output, his classical works being performed only very rarely. These are what Allison Brewster Franzetti has characterised collectively as ‘the unknown Piazzolla’. This is a shame because this is where some of Piazzolla’s most interesting music is to be found. If you’d like to explore Piazzolla’s more classical side, the Tango Suite is a great place to start.

The Tango Suite was commissioned by the formidable Brazilian classical guitar duo, the Assad Brothers, who premiered it in Paris in 1984. The work broke new ground within the guitar duo repertoire, employing a dazzling array of resources, including numerous extended techniques and percussive effects.

Written in three movements, the work opens with echoes of Piazzolla’s evergreen Histoire du tango, but soon reveals itself as a relatively more complex, mature and ‘contemporary’ piece – that is, without ever descending into pure academicism. Indeed, one of the delights of this work for me is the way in which Piazzolla seems able to seamlessly syncretise popular material with more experimental methods; his talent for naturalistically reconciling the topical with the abstract. Even in Piazzolla’s more classical works, however, the tango is never far away (albeit more, or less, sublimated) and in this piece we can also hear tango rubbing shoulders with some of Piazzolla’s other major influences: jazz, Bach, Ginastera and even Stravinsky. The result is an ‘urban’ species of ‘classical cool’ which simultaneously challenges its performers to demonstrate their grasp of the ‘swing’ of the tango whilst also having to negotiate the exacting demands of the most difficult of classical guitar techniques. I think this urban cosmopolitanism is one of the reasons why Piazzolla has found particular favour today amongst slighter younger audiences.

The slower, second movement is very lyrical, conveying the more languid, sultry side of the tango, and this offers some brief respite before the piece launches into the exhilarating, relentless drive of the final movement. Here, Piazzolla lets his imagination really run wild, lurching capriciously between ideas, moving restlessly between unexpected harmonies. A (slightly) more contemplative middle section cedes to the finale: an unstoppable rollercoaster ride of further adventures through precarious harmonic and rhythmic turns. This final movement in particular interweaves a pleasing dichotomy of melody and rhythm that is particular only to Piazzolla.

There aren’t many recordings of ‘Tango Suite’ out there – I suspect for the same reason that there are so few live peformances – because, technically speaking, it’s at the harder end of the guitar repertoire. The best version I’ve come across to date is the 1998 recording by Argentine guitarists Walter Ujaldón and Marcela Sfriso. Ujaldón was on the guitar staff at the Conservatorio Nacional Superior when I was there in 2002 and I had the pleasure of hearing him perform it with Sfriso in concert. Unfortunately, their album, titled ‘Solos y duos: Piazzolla, Britten, Bach, Ginastera, Kleynjans’, has long been deleted and is difficult to get hold of these days, but I have seen second-hand copies advertised for sale on the internet, so it’s worth doing a search.

In addition, the key version to listen to is the world-premiere recording, ‘Latin American Music for Two Guitars,’ by the Assad Brothers, for whom the piece was written. The Assads are undoubtedly brilliant in everything they do, but for me this interpretation lacks the more authentic, slower tempo and Argentinian rubato of Ujaldón/Sfriso in favour of a more typically frenetic Brazilian attack. In this, the piece loses some of the sensuality and pathos that lends it greater ‘tangitude’ and local meaning.

Por el futuro: hagamos que las relaciones culturales cuenten en una sociedad global post-crisis

La pandemia del Covid-19 está teniendo un efecto demoledor en la labor de las relaciones culturales internacionales. Actividades y colaboraciones en todo el mundo han sido canceladas o pospuestas y la mayoría de espacios culturales se han visto forzados a cerrar sus puertas. Artistas y organizaciones, incluyendo nuestros miembros, se han visto gravemente afectados por la abrupta interrupción de sus actividades, que dependen en gran medida del encuentro y la colaboración entre personas más allá de las fronteras. Los Agentes en el sector han acudido al ámbito digital como respuesta inicial, pero, ¿cómo seguir avanzado a largo plazo? ¿Cómo podemos garantizar que, después de la crisis, las relaciones culturales continúen aportando confianza y entendimiento mutuos entre el entorno europeo y el resto del mundo?

- Consecuencias del Covid-19 en el ámbito de las relaciones culturales

Con el objetivo de obtener una visión de conjunto de la situación que enfrentan las relaciones culturales, EUNIC está documentando y analizando el impacto de la crisis en sus miembros. Algunas de las conclusiones más relevantes son:

- Se estima que los miembros de EUNIC han perdido alrededor de 6,6 millones de euros de ingresos debido al cierre de sus centros.

- El 85% de nuestros miembros ha cerrado temporalmente al menos la mitad de sus sedes en el mundo

- Al menos la mitad de ellos se han visto obligados a cancelar contratos con artistas y expertos

- Más de la mitad prevé suspender o reducir sus programas

- El 13% anticipa una reducción de plantilla

- Entre los miembros que han necesitado buscar nuevas fuentes de ingresos, el 40% ha recurrido a cobrar por su oferta cultural y el 30% ha solicitado financiación privada

- El 85% de los miembros no reúnen las condiciones para solicitar fondos gubernamentales de emergencia

Gobiernos nacionales, regionales y locales, así como otros actores del sector, han tomado medidas importantes para mitigar los efectos de la crisis y la Comisión Europea ha lanzado la plataforma Creatives Unite para recoger estas iniciativas. Nosotros nos unimos al conjunto de redes, organizaciones y personas de toda Europa que han llamado la atención sobre la grave situación de la cultura en esta crisis, demandando respuestas contundentes en apoyo al sector (Culture Action Europe, European Cultural Foundation, Europa Nostra, Miembros del Parlamento Europeo y otros muchos).

Sin embargo, muchos países de la Unión Europea se están centrando en dar una respuesta exclusivamente a nivel nacional, dejando de lado nuestra responsabilidad europea y global. Las barreras alzadas hoy por razones sanitarias no deberían convertirse en la norma. Este no es el momento en el que los países deban mirar únicamente hacia dentro.

Solo podremos superar esta crisis, recuperar el sector cultural global y restablecer las relaciones internacionales haciendo posible que personas de todo el mundo puedan encontrarse y colaborar libremente.

2. La importancia de las relaciones culturales internacionales

Las relaciones culturales generan un espíritu de diálogo y solidaridad global, y pueden ser la clave de una solución que nos mantenga conectados, resilientes y en un saludable estado mental ante la situación actual, lo que, a la vista de los enormes desafíos globales, se revela de una importancia sin precedente. Las relaciones culturales refuerzan la idea de una Europa compartida, aumentando su autorreflexión hacia una conciencia común de los valores compartidos.

Las relaciones culturales son fundamentales para generar confianza y entendimiento mutuos y construir un mundo más pacífico acercando a las personas a escala global. Las relaciones culturales han jugado un importante papel a la hora de promover relaciones pacíficas entre personas de todo el mundo.

Dado que todos los Estados miembros de la Unión Europea dedican una cantidad considerable de sus presupuestos a las relaciones culturales (2.900 millones de euros en 2019), y al mantenimiento de redes mundiales de institutos culturales, (con más de 2.500 centros y 35.000 empleados), dichas relaciones culturales han sido durante décadas un instrumento destacado de la política exterior.

Si bien la participación en la vida cultural mejora la salud y el bienestar, las relaciones culturales pueden repercutir positivamente en la resolución de conflictos, la construcción de la paz y la elaboración de políticas relacionadas. La investigación ha demostrado que el acceso a la cultura es el segundo factor más determinante para el bienestar psicológico.

La cultura crea empleo y competitividad y puede jugar un papel un papel relevante en la recuperación económica global. El empleo en el sector cultural de la UE hoy en día asciende a 8,7 millones de personas, convirtiendo a este sector en uno de los grandes empleadores, proporcionando 2 veces y media más trabajo a los europeos que el sector de la automoción. Con un superávit comercial de 8.700 millones de Euros en bienes culturales, se estima que los sectores cultural y creativo contribuyen con un 4.2% al PIB comunitario (EU Agenda for Culture, 2018).

La economía global está impulsada por la creatividad cultural, la innovación y el acceso al conocimiento. Las industrias cultural y creativa representan alrededor de un 3% del PIB global y 30 millones de puestos de trabajo (UNESCO, 2016). Si bien el comercio mundial de productos creativos se ha duplicado con creces entre 2002 y 2015, creciendo a un ritmo del 7% anual, la creación de capacidad mutua y el fortalecimiento de las industrias culturales y creativas estimulan el empleo, capacitando a los jóvenes y a las mujeres para contribuir a unas economías resistentes (UNCTAD, 2019).

3. Formas de avanzar

Para contrarrestar el aislamiento de las políticas culturales se necesitan iniciativas transnacionales que conecten artistas y profesionales más allá de las fronteras, para que el intercambio cultural y el diálogo intercultural puedan así florecer.

Para avanzar en la construcción de la paz es necesario llegar a las personas, a través de la cultura, más allá de las fronteras a escala mundial. Como dijo el AR Josep Borrell en el Día Mundial de la Diversidad Cultural para el Diálogo y el Desarrollo, “tres cuartas partes de los mayores conflictos en el mundo tienen una dimensión cultural. La reducción de la brecha entre culturas es urgente y necesaria para la paz, la estabilidad y el desarrollo”.

Los sectores culturales locales en todo el mundo necesitan apoyo. Muchos países no están en condiciones de dedicar recursos adicionales a los sectores culturales. En este sentido, la UE puede dar un paso adelante y desarrollar, junto con las autoridades y organizaciones de los países asociados, programas de apoyo que ayuden al sector.

La movilidad internacional no debe detenerse. Mientras que cuestionar nuestros hábitos de viaje y reducirlos por el bien del medio ambiente es absolutamente necesario, nuestras relaciones de amistad con el mundo dependen de que las personas puedan encontrarse. Solo aprendiendo unos de otros podremos desarrollar la confianza y deshacernos de nuestros miedos y prejuicios.

Nuestro Proyecto European Spaces of Culture experimenta con nuevas formas de participación en las relaciones culturales y debería ampliarse. Estos modelos pueden servir como formas de salida de la crisis, comenzando una nueva forma de hacer cultura en el futuro: justa, igualitaria y basada en la escucha y el aprendizaje mutuos, la co-creación y un enfoque de abajo arriba.

Debemos adaptar nuestra forma de trabajar en el ámbito digital, encontrando nuevas formas híbridas de hacer relaciones culturales más allá de la crisis. Aunque la necesidad de reuniones cara a cara seguirá siendo permanente, el 81% de los miembros de EUNIC está estudiando la posibilidad de desarrollar formatos híbridos que combinen la presencia física con el contenido virtual. Y mientras exploramos los medios digitales, no debemos dejar a nadie atrás. Las comunidades sin infraestructura digital también deben ser incluidas en los programas que desarrollamos para unir a las personas.

Al igual que el patrimonio cultural es importante para los europeos, ciertamente también lo es para los habitantes de otros continentes. El 71% de los europeos está de acuerdo con la afirmación “vivir cerca de lugares vinculados con el patrimonio cultural europeo puede mejorar la calidad de vida” (Eurobarómetro 466). Trabajar en el patrimonio cultural en el marco de las relaciones culturales puede ser un punto de apoyo para unir personas y comenzar un discurso honesto y significativo con comunidades en otros países sobre nuestro pasado y nuestras responsabilidades

Las relaciones culturales juegan un papel importante en la recuperación económica global. La creación de bienes culturales y la participación en la cultura crean una cantidad significativa de empleos. Empleos que aportan valor, empatía, paz y sentido de pertenencia a las comunidades. Invertir ahora en cultura junto con nuestros socios es la decisión más acertada para salir de la crisis lo más indemnes posible.

4. Lo que debemos hacer ahora

“La cultura está en el corazón del progreso y puede jugar un papel fundamental en el periodo posterior a la actual crisis”. Ante esta declaración conjunta del AR Josep Borrell y la Comisaria Mariya Gabriel publicada el 21 de mayo de 2020, debemos aprovechar la oportunidad de situar las relaciones culturales en el centro de nuestros esfuerzos para combatir los efectos y repercusiones del brote de coronavirus. Dado que la cultura ha demostrado ser esencial para sostener nuestras sociedades en momentos de crisis, es preciso protegerla de los recortes presupuestarios en los marcos financieros posteriores a la crisis y aumentar sustancialmente los presupuestos de la UE destinados a estos sectores.

Por ello, hacemos un llamamiento a todos los actores de las relaciones culturales para:

- Implementar medidas para que la cultura pueda conectarnos a nivel mundial, compartir valores para mejorar las relaciones internacionales y aprender de las prácticas de cada uno, incluyendo el apoyo a los miembros de EUNIC

- Mirar más allá de las fronteras nacionales y aunar esfuerzos para gestionar la crisis de forma multilateral

- Demostrar el poder de la cooperación efectiva ante los desafíos globales de nuestro tiempo, incluyendo una mejor coordinación de todas las actividades de la UE en el ámbito de las relaciones culturales

- Invertir más en una política exterior conjunta de la UE que conceda un papel adecuado a las relaciones culturales.

- Fortalecer las estructuras organizativas y financieras de la UE, incluyendo la Comisión Europea y el Servicio de Acción Exterior Europeo, para que se involucren en la cultura

- Continuar invirtiendo en cooperación cultural europea, resistirse a los recortes presupuestarios tanto a las redes culturales como a la creación de capacidad conjunta y a las actividades sobre el terreno en el ámbito de las relaciones culturales

- Apoyar las iniciativas multilaterales dentro de la estrategia de la Unión Europea para las relaciones culturales internacionales

- Continuar invirtiendo en cultura dentro de los programas de cooperación al desarrollo

- Fortalecer el componente internacional de Europa Creativa

- Fortalecer las iniciativas existentes, tales como European Spaces of Culture, que puedan contribuir a la superación de la crisis

- Lograr que el apoyo a los entornos culturales locales sea una prioridad global

- Participar en formas digitales e híbridas de trabajar en las relaciones culturales

- Aprender mutuamente de las prácticas actuales y futuras de cada uno a través de procesos de abajo-arriba

Juntos, EUNIC y sus miembros, están preparados para hacer su parte.

For the future: Make cultural relations count in a post-crisis global society

The Covid-19 pandemic has a crushing effect on the work of international cultural relations. Activities and collaborations worldwide are cancelled or postponed, while most cultural venues are forced to close their doors. Artists and organisations, including our members, are severely affected by the abrupt discontinuation of their activities, which rely so heavily on people coming together to collaborate across borders. Actors in the field moved to the digital realm as an initial response, but how to go forward in the longer term? How can we ensure that, after this crisis, cultural relations continue to bring trust and understanding between the people of Europe and the wider world?

- Covid-19 effects on cultural relations work

In order to get an overview of the situation confronting international cultural relations, EUNIC is documenting and analysing the impact of the crisis on its members. Some major findings:

- An estimated 6.6 million euros of income was lost by EUNIC members due to branches closing.

- 85% of members temporarily closed at least half of their branches worldwide.

- Almost half were forced to cancel contracts with artists and experts.

- More than half foresee discontinuing or downsizing programmes.

- 13% are concerned about staff downsizing.

- Of those members who had to resort to new ways of gathering income, 40% have started to charge for their cultural offerings and 30% have applied for private funding.

- 85% of members are not eligible to apply for emergency government funding.

National, regional and local governments and other actors have taken important measures to mitigate the crisis and The European Commission has launched the Creatives Unite platform to gather such initiatives. We join a chorus of networks, organisations and individuals across Europe who have flagged the dire situation of culture in this crisis, calling for strong responses in support of the sector (e.g. Culture Action Europe, ECF, Europa Nostra, Members of the European Parliament, and many more).

However, many EU countries are focusing only on a response at national level, leaving behind our joint European and global responsibility. Barriers currently raised for public health reasons should not remain the norm. Now is no longer the time for countries to look inwards.

The crisis will only be resolved, the global cultural sector will only recover, and international relations will only be restored if peoples of the world are enabled to meet and collaborate freely with one another.

2. The importance of international cultural relations

Cultural relations generate a spirit of dialogue and global solidarity. Cultural relations can be at the heart of the solution to remain connected, resilient and in good mental health in the current situation. In the face of a truly global challenge, this is more important than ever. Cultural relations strengthen the idea of a shared Europe, increasing its self-reflection towards a common awareness of joint values.

Cultural relations are key in creating trust and understanding and a more peaceful world by bringing people together on a global scale. Cultural relations have played an important role in fostering peaceful relations between the peoples of the world. With all EU Member States dedicating a considerable amount of their budgets to cultural relations (EUR 2.9 billion in 2019), maintaining world spanning networks of cultural institutes (more than 2,500 branches with more than 35,000 staff), cultural relations have been over decades a prominent tool in foreign policy.

While cultural participation improves health and well-being, cultural relations can positively impact conflict resolution, peace building, and related policy development. Research has demonstrated that cultural access is the second most important determinant of psychological well-being.

Culture creates jobs and competitiveness and can play an important role in the global economic recovery. EU cultural employment is today at 8.7 million, making the sector one of the largest employers and providing jobs for 2.5 times more Europeans than the automotive sector. There is a EUR 8.7 billion trade surplus in cultural goods, and cultural and creative sectors are estimated to contribute 4.2% to EU gross domestic product (EU Agenda for Culture, 2018).

The global economy is driven by cultural creativity, innovation and access to knowledge. Cultural and creative industries represent around 3% of the global GDP and 30 million jobs (UNESCO, 2016). While global trade in creative products has more than doubled between 2002 and 2015, growing at a rate of 7% annually, mutual capacity building and the strengthening of the cultural and creative industries stimulate jobs, empowering youth and women to contribute to resilient economies (UNCTAD, 2019).

3. Ways forward

To counter the isolation of national cultural policies, transnational initiatives connecting artists and professionals across borders are being called for so that cultural exchange and intercultural dialogue can flourish.

To continue peace building, reaching out to people worldwide through culture is needed. As HR/VP Josep Borrell said on the World Day for Cultural Diversity for Dialogue and Development, “three-quarters of the world’s major conflicts have a cultural dimension. Bridging the gap between cultures is urgent and necessary for peace, stability and development.”

Local cultural sectors worldwide require support. Many countries are not in a position to devote additional resources to the cultural sectors. Here the EU can stride ahead and develop, together with authorities and organisations in partner countries, support schemes that help.

International mobility must not stop. Whereas questioning our traveling habits and reducing them for the sake of the environment is absolutely necessary, our friendly relations with the world depend on people meeting. Only by learning about each other can we develop trust and shed our fears and prejudices.

Our project “European Spaces of Culture” tests new ways of engaging in cultural relations and should be enlarged. The models found here can serve as way out of the crisis, starting a new kind of doing culture in the future – fair, equal, based on mutual listening and learning, co-creation and a bottom-up approach.

We must adapt our way of working in the digital realm, finding new, hybrid ways of doing cultural relations beyond the crisis. As the need for face-to-face meetings will remain permanent, 81% of EUNIC members are looking at developing hybrid formats that combine physical presence with virtual content. And while we are exploring digital means, we must leave no one behind. Communities without digital infrastructure must also be included in the programmes we develop to bring people together.

Cultural heritage is important for Europeans, as it is for the people from other continents. 71% of Europeans agree that “living close to places related to Europe’s cultural heritage can improve quality of life” (Eurobarometer 466). Working on cultural heritage in the framework of cultural relations can be a steppingstone to bring people together and start an honest and meaningful discourse with communities in partner countries about our past and responsibilities.

Cultural relations can play an important role in the global economic recovery. Creating cultural goods and engaging in culture does create a significant amount of jobs – jobs that bring value, empathy, peace and a sense of belonging to communities. Investing in culture together with our partners is the right thing to do now to emerge from this crisis as unscathed as possible.

4. What we must do now

“Culture is at the heart of progress: it can play a truly key role in the aftermath of the current crisis.” Along with this joint statement by HR/VP Josep Borrell and Commissioner Mariya Gabriel published on 21 May 2020, we must seize the opportunity to put cultural relations at the core of our efforts to combat the rippling effects of the coronavirus outbreak. As culture has proven to be essential in sustaining our societies in moments of crisis, culture must be protected from budget cuts in the post-crisis financial frameworks and EU budgets for culture must be substantially increased.

Therefore, we call on all actors in cultural relations to:

- Install measures so that culture is enabled to connect people worldwide, share values to improve international relations and learn from each other’s practice – including supporting EUNIC members

- Look beyond national borders and join efforts multilaterally to manage the crisis

- Demonstrate the power of effective cooperation in meeting the global challenges of our time, including better coordination of all EU activities in cultural relations

- Invest more in a joint EU foreign policy that includes an appropriate role for cultural relations

- Strengthen the organisational and financial set-up in the EU, including the European Commission and the European External Action Service, to engage in culture

- Continue investing in European cultural cooperation, resist cutting budgets for networks, co-capacity building and cultural relations activities on the ground

- Support multilateral initiatives under the EU strategic approach for international cultural relations

- Continue investing in culture within development cooperation programmes

- Strengthen the international component of Creative Europe

- Strengthen and continue existing initiatives such as “European Spaces of Culture” that can contribute to the overcoming of the crisis

- Make support to local cultural scenes worldwide a priority

- Engage in digital and hybrid ways to work in cultural relations

- Learn from each other’s current and future practice by a bottom-up process

Together, EUNIC and its members are ready to do their part.

«My experience in Argentina was life-changing and proved decisive in setting me on a career path in music»

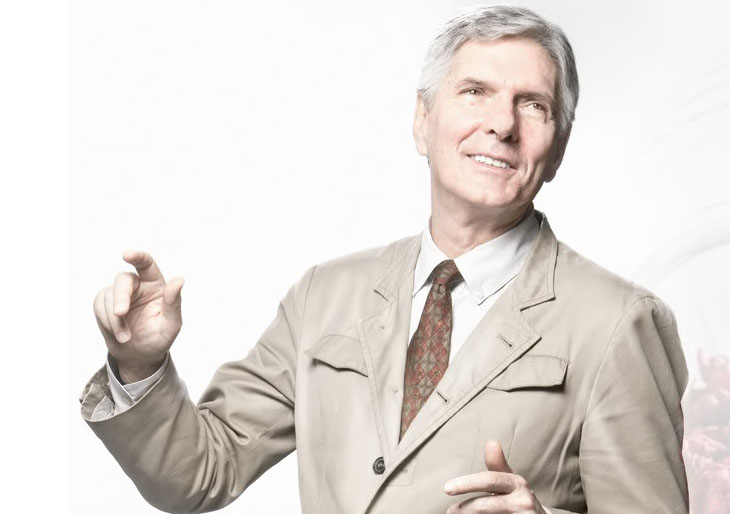

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our eighth guest, Helen Glaisher-Hernández, pianist, Latin Classical music expert and artistic director of the Iberian & Latin American Music Society (ILAMS).

For the past four years, ILAMS and Instituto Cervantes London have co-produced the ECHOES Festival of Latin Classical Music, taking place across some of the capital’s most prestigious classical music venues, such as St Martin-in-the-Fields, the Royal Academy of Music and St James’s Piccadilly.

Following two degrees in Spanish and French at the University of Cambridge (Corpus Christi College), including a year abroad studying Piano at the Conservatorio Nacional Superior in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and an MMus in Piano at Trinity College of Music in London, Glaisher-Hernández now combines her two great loves – music and hispanicity – as a concert pianist, event producer and educator specialising in Luso-Hispanic repertoire.

You often say that your two great loves are music and hispanicity. How do you combine both in your life?

Well, I was born in the UK, in Sheffield, but am also half-Spanish by virtue of my Canarian mother, who is a tinerfeña. As a child, I was quite wilful and typically replied in English whenever my mother spoke to me in Spanish. I understood her perfectly well, though, because she had persevered in speaking her mother tongue to me regardless ever since I was born. (Now my Spanish is near-native, and I feel very grateful that she did!) I perfected my Spanish at secondary school and since this was my absolute favourite A-Level subject, I then opted to read Spanish (and French) at university.

Having also studied piano from the age of four, and achieving an advanced level in my teens, it occurred to me that I could use the requisite ‘Year Abroad’ of my Languages degree to further my playing by studying piano in a Hispanic country. I’d been to Spain so many times by that point, and having never left Europe, South America beckoned to me in a much more enticing way. After investigating the options, I discovered that Argentina housed one of the best musical institutions on the continent, the Conservatorio Nacional Superior ‘López Buchardo’ in Buenos Aires, and the Dean there kindly agreed to let me enrol on the first year of their undergraduate Music degree. My experience there was life-changing and proved decisive in setting me on a career path in music – something I’d never seriously considered until then.

When I returned to England I made plans to audition for music college here after my graduation from university, and was accepted at Trinity College of Music (as it was then known); I wanted to study with a particular tutor there, the Venezuelan pianist, Elena Riu. From the off I played a lot of Luso/Hispanic music with a view to specialising in that repertoire professionally.

…And ten years later that’s essentially what I’m still doing. Of course, I play all sorts of composers (I’m not a Latin ‘fetishist’, as some people seem to think) but with my particular background, and after so many years of studying Hispanic ‘letters’ (including Hispanic literature, film, theatre and visual arts) at university, it gives me a lot of satisfaction to bring my cultural knowledge and experience to performing and promoting this wonderful but highly-neglected music; music which I sincerely believe can count itself amongst the finest ever written anywhere. In fact, I would argue that no non-native musician can authoritatively tackle this repertoire without having enjoyed a considerable level of immersion in the vast, diverse and extremely rich culture that is Hispanic culture. And I would cite cultural understanding (or a lack of it) as the main challenge facing international promoters of Latin classical music today.

Since graduating from Trinity, I feel privileged to have performed at some of the UK’s most prestigious venues, and to have been able to collaborate with some truly great artists from the Latin classical music field. At the moment I’m working on the release of my first album, which explores the globalisation of the tango through its operatic roots. The recording also features the Argentine tenor, Leonardo Pastore, soprano, Jaquelina Livieri, and mezzo-soprano, Florencia Machado – all leading opera singers in Argentina, alongside various instrumentalists from the Buenos Aires Philharmonic. Don’t ask me exactly when it’s coming out, because the Coronavirus pandemic has thrown uncertainty on all our plans, but watch this space!

Since you have a degree in Spanish and French from Cambridge University, did languages open doors to you?

So (without wishing to brag!), I actually have two degrees from Cambridge: an MA in ‘Modern and Medieval Languages’ and an MPhil in ‘European Literature’, which I decided to ‘tag on’ to my first degree before switching to Music. I did this for the entirely flippant reason that all my friends were doing it, and I thought it would be ‘fun’ to continue to maintain some sort of academic activity whilst I took a year to prepare for Music auditions. Of course, as it turned out, the MPhil was very intense and necessarily absorbed most of my time and headspace, and I ended up delaying my musical plans for another year. My MPhil, however, unexpectedly turned out to be one of the best things I’ve ever done. After four years of achieving only average-to-good marks as an undergraduate, I seemed to blossom as a postgraduate, to the extent that the Faculty subsequently offered me funding to stay on for PhD. …But I’d been too seduced by music by that point to abandon my plans. Nonetheless, I now see that year as an essential part of my education, and I particularly enjoyed working on areas such as Argentine film and the plays of Lope de Vega, whilst for my dissertation I explored the Canarian cross-currents present in Shakespeare’s The Tempest. During this year I also studied a considerable amount of Postcolonial Theory, which continues to colour my understanding of the world, and its music, to this day.

As for the opening of doors, I never really contemplated pursuing a career in Languages in the literal sense – the idea of becoming an interpreter, for example, never appealed to me, although I think it almost goes without saying that having Languages can only improve one’s career prospects in any sector. For me, the importance of Languages is not so much utilitarian as humanistic – and increasingly so in these troubled times in which we live. We Brits are infamous throughout the world for our relative reluctance to learn languages, our misplaced indolence predicated on the convenient reality that the rest of the world is more than adept at speaking ours. But instead of bringing increased peace and enlightenment, the new digital century has delivered an overwhelming intensification of globalisation that we are struggling to assimilate, and which has instead only led to culture wars, the hardening of politics and the polarisation of societies worldwide.

The mainstream media have driven public discourse into a narrow dialectic by overwhelmingly tackling these problems as political ones, but in my opinion our problems are fundamentally cultural; the result of a naive and incoherent identity politics (on all sides) spouted by people unversed in any kind of nuanced cultural thinking. A consensus of the population seem to view investment in the cultural industries as a merely optional adjunct to the ‘utilities’ of the economy, but as Winston Churchill eloquently warned us, “Ill fares the race which fails to salute the arts with the reverence and delight which are their due.” I believe that culture is the answer to all our social and political problems. In order to solve the challenges of globalism we must do better at understanding each other – the survival of the planet and our species depend on it. I consider language to be the keystone of any culture, and so in that sense, we must all learn languages. …And by the way, music is also a kind of language!

Your year abroad studying piano at the Conservatorio Nacional Superior in Buenos Aires, how was it?

If I tell you that I really didn’t want to come back at the end of the year, that might give you some sense of how devastatingly incredible it was. I went out there with consciously low expectations, never dreaming that I would literally have the time of my life. I’ve been back to Argentina many times since then, so it seems like a second home now, but I still remember how it felt that first time, and it makes me a little nostalgic to think about it. It was a very special experience that had a profound and lasting effect on my life in many ways.

I think the first time you leave Europe – as a European, I mean – it’s always something of an experience, like landing on a different planet. Argentina is a place where crazy things happen to you. Having said that, I soon felt like I strangely belonged there. Argentinian people are incredible characters, and I was quickly seduced onto their wavelength. To an extent, Argentines have a reputation for being corrupt and duplicitous, but that wasn’t my experience at all, at least not in my personal relationships. On the contrary, I think Argentines are quite simply the best people on the planet – the most generous, witty, intellectual and genuine you’ll ever encounter. Everything runs deep. When they say something, they mean it, and they’re all philosophers, down to the taxi drivers and the person checking out your shopping at the supermarket. They blew my mind constantly; every conversation was a revelation. Once they befriend you, the bond is permanent. I still have a lot of the same friends I made there 17 years ago, and they’re some of the best friends I ever had.

The city, by extension, and despite its size, is also warm and welcoming – it embraces you as you walk down the street. I lived in a student residence with Argentinians from all corners of the country who had also come to study in the capital, as well as a few Brazilians. Supposedly, the building – a traditional 19th-centuy house in the Barrio Norte district – had originally been a brothel, and it was definitely haunted – I had some unusual experiences there! There was never a dull moment.

At the time of my arrival in 2002, Argentina had just been plunged into an economic crisis and the peso had lost more than two thirds of its value overnight. Argentinians suffered terribly, but for me this was effectively like winning the lottery. It meant that me and my pounds sterling could jet-set around the country taking 5-star mini-breaks, and eat out every day of the week. I didn’t have a care in the world. It was nice to temporarily feel the liberating effects of relative wealth, although thinking about it now, it does seem a little decadent given what was going on around me.

Studying at a conservatoire for the very first time was also an awe-inspiring experience. …Bearing in mind that I was probably the first Briton to ever study there in the history of the institution. My fellow students couldn’t quite understand why on earth I would leave England to go there. I was something of a curiosity, and all the students knew who I was and wanted to be my friend. (It’s my conclusion that Argentines have a profound admiration for the British. Although they often pretend to hate us, I think they’d secretly like to be us.) I had a wonderful piano teacher, Graciela Beretervide (a former student of Arrau), with whom I studied Handel, Beethoven, Chopin and Rachmaninov. She was like a mother to me, and we still keep in touch. I also attended all the first-year modules in subjects such as Critical Theory, Musical Forms, Gregorian Chant, Alexander Technique, and so on. Studying classical Music History from the point of view of the third world, for example, was very eye-opening. The best part was that, not being a permanent student, I didn’t have to actually sit any of the exams, so I just dedicated myself to taking it all in and having a great time! By night I went out to all sorts of concerts with my friends.

It was a beautiful time. I walked around in a constant state of euphoria, with a permanent smile on my face. But it was ultimately an artificial situation which inevitably had to end. Coming back to England to do my finals was, by comparison, pretty depressing. But as Eladia Blázquez said in her famous tango, ‘siempe se vuelve a Buenos Aires’. (‘You always go back to Buenos Aires’.) And so I have, several times, and I’m sure I wild find myself there again…

How did you start to appreciate the music of different cultures and traditions from an early age?

Mainly because my father was British and my mother is Spanish, and they each tended to listen to very different things. My mother liked to have Canarian folk music on in the background, and other types of Hispanic music – Mocedades, Julio Iglesias, Rocío Jurado…as well as Latin American artists such as Mercedes Sosa, Los Panchos and Los Paraguayos.

My father, being of a slightly older generation to my mother, played a lot of music from the 1940s onwards – Glen Miller and big-band swing music, George Formby, crooners like Bing Crosby, Hollywood musicals… He also liked the pop music of the 60s and 70s. In his record collection he had Shirley Bassey, The Carpenters, Burt Bacharach, ABBA, The Bee Gees, Neil Diamond, Neil Sedaka… My father was a businessman by trade, but used to organise concerts for the Variety Club to raise money for charity – he put on huge events around Yorkshire with artists such as Matt Monroe and The Nolan Sisters.

Neither of my parents ever had any kind of musical training, although they were (are) naturally very musical and respectively very decent singers (they were always singing around the house) – I always thought both of them could have been professionals. I think the point at which they intersected musically was Nat King Cole’s En español – an album which now reminds me of them and makes me very sentimental.

In terms of classical music, I was exposed to a lot of the standard orchestral repertoire at the local youth orchestra as a teenager where I played violin, alongside things I heard on Classic FM. During my Sixth Form I also did an ALCM diploma and studied a lot of the ‘Great’ composers.

My elder brother, Mik, was a professional musician, however – he was the drummer in a successful Sheffield band of the 80s and 90s called the Comsat Angels. They had some brilliant songs, the most famous probably ‘Independence Day’. When I was a teenager, Mik would ‘corrupt’ my listening habits by making me mixtapes of the Beatles, and various rock and grunge bands I’d never heard of, like Juliana Hatfield. Obviously at that time my own interests came from what was in the Top 40, i.e. Brit Pop – Pulp (also a Sheffield band) and Radiohead probably the most. Plus any number of pop artists from that time; my biggest guilty secret being Bon Jovi. (Still is.)

As a teenager I also had musical escapades in Spain each summer when my parents would send me off to Tenerife to spend the holidays at my grandparents’ house. My aunties used to take me out clubbing with their friends and we danced to a lot of salsa. A lot of the Latin pop they played on the radio also rubbed off on me. Mónica Naranjo, Juanes, Alejandro Sanz…

You could say that my musical tastes have become very eclectic, but I only really divide music into two types: good and bad. But I like to keep an open mind and am always listening to new things. I would say music is my addiction.

You have a special passion for chamber music and vocal accompaniment. How did you become interested?

I first ‘discovered’ the beautiful thing that is chamber music at the conservatoire in Argentina. We had a weekly chamber music class in which we all had to form small ensembles and perform in front of each other. There was also a strong feeling of solidarity within the class which helped to convert me. As a pianist, the concept of playing with other people was entirely new to me. The life of a pianist is a relatively solitary one, and you really need a certain ego and temperament to want to perform publicly as a soloist – a temperament I don’t really possess. I find the experience a bit like navel-gazing in public, whereas when you collaborate with others it’s a more sociable and humbling experience. …Plus you get the benefit of seeing things from different perspectives.