Blog del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín

Torre Martello

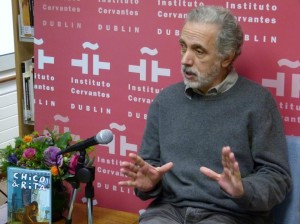

Interview with Fernando Trueba

Interview with Fernando Trueba held on the 4th of November 2012 in the Damaso Alonso Library, Instituto Cervantes Dublín, on the occasion of his participation in the roundtable “Words and Images: Cinema and Literature” with Mark O’Halloran and Javier Mariscal for the ISLA Festival 2012.

Fernando Trueba (Madrid , Spain , 1955) is a writer, editor and film director . Between 1974 and 1979 he worked as a film critic for El País and in 1980 he founded the monthly film magazine Casablanca, which he edited and managed for the first two years. In 1992 his film Belle Epoque won 9 Goya Awards , and in 1993 it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. In 1997 he published his book Dicionario del Cine (Dictionary of Cinema) and is editor of the Diccionario del Jazz Latino (Dictionary of Latin Jazz) (1998). In 2010 he directed , with designer Javier Mariscal, the animated film Chico y Rita, which received the Goya for best animated film which was selected for the Academy Awards in the category of Best Animated Film . His most recent film is El Artista y la Modelo (The Artist and the Model) (2012).

Alfonso Fernández Cid: Fernando, I have it engraved in my memory that when you received the Oscar for the film Belle Époque, you said you did not believe in God but in Billy Wilder. Do you still keep that faith?

Fernando Trueba: In Billy Wilder? Of course! For what reason would I ever lose it? There are many directors that I admire and I try to learn from, and he’s one of them. For me, directors such as Renoir, Truffaut, Bresson, Lubitsch , Preston Sturges and many others have been crucial in my development and in my life. But Billy Wilder is part of that group which has become part of me, for better or for worse.

I ‘ve always thought that Billy Wilder is the best screenwriter that ever lived. Well, II think it’s silly to claim that someone is the best director ever, for one day you may think that it is Renoir, and another day it is Lubitsch, and another it’s John Ford, and every day you’re right . Nevertheless, I challenge anyone to show me the proof that there is a better scriptwriter than Billy Wilder. Bring me the scripts with all dialogues, how they are written, structured, and I’m willing to take whatever time necessary to analyze and discuss them, because I’m sure that there is no such scriptwriter better than Billy Wilder. Never!

More than faith, it is a conviction. Faith is believing in something without seeing it. I think beyond seeing and reading, there is a kind of revelation that is felt when you see the masterpieces of Billy Wilder. You keep watching them, and the years go by and you look at them again. You know them by heart and think that you will feel nothing new watching Sunset Boulevard or The Apartment or Double Indemnity or Some Like It Hot. But you see them again and that feeling of infinite admiration for these intelligent, well-made works returns.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: How do you arrive at such a cinematic project as Chico y Rita, in which you managed to involve Bebo Valdes and [Javier] Mariscal?

Fernando Trueba: It came out of friendship. Friendship is one of the biggest incentives in my life, something that is at the source of many things I’ve done. In this case, it has been my friendship with Mariscal. It all started with Calle 54. He produced the artwork for the documentary. Then I started making records and I continued to ask him to design them for me. Because I love what he does and because we understand each other very well. I laugh a lot with him too.

One day he tells me “I’ll die without having done something I would have really loved to do: to make an animated feature film.” And I said “Surely you’ve had a thousand proposals right? Why haven’t you done one yet?” And he said “Yes, but a movie like this is not a question of hours, but of months, years, drawing by hand, bent over a table, and whenever anybody offered me anything, it was for a story I did not like. I will not lose my life, my eyes and my arms to draw a story that I do not like.”

Of course, for me animation is a totally alien world, I had never considered it before. He said to me, “For example, you will not take animation and this kind of stuff seriously. You would never give the time to write a script for an animated film.” He caught me by surprise. In essence, these conversations began the project. One day, in his study, I saw drawings of old Havana. I was overcome with enthusiasm when I saw them, “How beautiful!” I said. “This is what you need to do! This is the movie that I must make! A film in your Havana, Mariscal’s Havana. That would be spectacular!” And so it began. He said: “Yes , but it must have music.” “Man, if its a story in Havana and the Cuban people, it will be difficult for it not to have music.” “Yes, but with lots of music,” he insisted. Then I said, “Why not do a story about musicians.” “Ok, a saxophonist and a singer who fall in love.” I said that was the worst Scorcese movie ever, New York New York, I hated that movie. “Why not a pianist so, and each time he plays the piano, we put in Bebo Valdés”. And so begins a movie, slowly, like everything in life, from a sentence , an image, a conversation. And then one needs to start writing and drawing for years.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: So the journey was a long one.

Fernando Trueba: Yes, first a script is produced and many versions of it are made. Then, to convince people to believe in the project and raise the money needed to do something so expensive, it is necessary to demonstrate the style in which the film would be made. Xavi [Mariscal] then began to draw characters , backgrounds, even maps were created as a demonstration. It took several years to find the people and the money to co-produce the project. Once this is found, we had to to start with storyboards, the characters, the hundreds of animators, drawing for two years. Actually, the process took seven years. What happened was that I, in the meantime, I wrote the screenplay for one movie, produced another couple of them, and I shot in Chile for El baile de la victoria (The Victory Dance). Otherwise, I would have died. There were parts of the production during which I could do nothing but wait: we had already recorded the sound, the music, and planned the camera movement. I just had to wait for the drawings to arrive and check that all was well.

It is very strange, animation. For me, it was like facing a completely new and different world. I have to say I enjoyed it like a child. Except the wait, how long it takes, the patience that one needs. Every time a drawing arrived from Xavi, every time I received a map, it was a joy, a tremendous rush. In fact we are planning two further projects. Chico y Rita has opened many doors for us. We have co-producers in several countries interested in what we are doing next. There’s a story that is very Xavi-esque, based on the characters from Garriris, one of his first comics, and he is working on the script with a screenwriter. As for me , I’m writing another one. We want to make them together. But the first project is more for Xavi, more for his world and and affairs , and the other is a draft of a story I want to tell.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: The great jazz fans always have a love affair with the music. What is your relationship with it?

Fernando Trueba: I have been through many different stages, because I discovered jazz as a teenager through my older brother. And it got the hook in me in a big way. I remember in those early days, when I was 14 , 15, 17, and I really liked Keith Jarrett, Dave Brubeck, McCoy Tyner. After this, there was a time in my life when I distanced myself from jazz, during my college years.

It was the era of free jazz, which was too free for me. It wore me out. It was a kind of music for musicians, too experimental. There is always a moment, in all the arts, when all the isms have been exhausted and a kind of delirium tremens is arrived at: “We will write without commas”, “let’s not paint , let’s put 27 phones on the floor and call it an installation” … At that point, I remove myself. Art, at the point in which communication is severed, no longer interests me. I need to understand things for them to excite me. So I left Jazz for a few years, but I returned to it through Latin jazz. I returned because I discovered a kind of energy in Latin jazz that made me come back.

Jazz is the most adventurous music that exists. Because one must have a wide musical knowledge, outstanding technical abilities, and then one must have the courage to improvise, to create, to let yourself be carried away, to let things happen themselves. That is very beautiful. I think authors also do this. There is a moment in the writing process where the hand moves by its own accord, and one sentence leads to another. This, in music, is only experienced by a jazz musician. A jazz musician will throw himself out the window without a safety net, and sometimes he will fly.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: You worked as a film critic.

Fernando Trueba: Yes, when I was very young, between the ages of 20 and 24, when I directed my first film. But I had already dreamt of making movies. Writing reviews was an opportunity to watch movies and get paid at the same time. Once, it was proposed for me to publish these reviews but I’ve always refused. They were sincere and passionate, but I think I was very young and did not have the capacity for it then. I do enjoy reading the reviews of Truffaut though, and in my house I have books by Manny Farber, Andrew Sarris, even writers who worked as critics such as Graham Greene, Alberto Moravia or Ennio Flaiano.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: What is the importance of critics – to what extent can they have an influence?

Fernando Trueba: I think that it is a very bad period for film criticism at the moment, because criticism, in the creative sense of cinema, has practically disappeared. Nowadays there is not one critic that I follow. Hoberman and Rosenbaum, from the US, interest me, but not entirely. I think Rosenbaum, in Chicago, is one person who is doing a good job, and has more merit still, because he is doing it in the United States, a country that is very self-absorbed…the United States does not look out at the world, but only at American cinema, with the exception of a select few in New York and San Francisco. Rosenbaum is mounting a crusade, telling people about Iranian cinema, Argentine cinema, Taiwanese cinema…he is the only critic I read with even a little interest.

I think that now, criticism has become very superficial. It is newspaper criticism, made hastily and in a hurry. In addition, the articles are very small, with little detail. You can not deal with a movie in a couple of lines.

For me, criticism is an act of love. Your enthusiasm should be contagious to others – to teach how to see something, to teach how to read something, to open a window onto an artistic work. This happened to me when I was young and read Truffaut. I read it and, suddenly, the desire to see a movie arose inside me. This is wonderful – when you become enlightened, when you are given clues, when you discover things that give you joy, when you feel your life is improved. And that is what I do not feel from critics nowadays.

I think the basic condition of the critic is to have the humility to recognize that what matters is the work, that he or she is an intermediary between the work and the public. A good critic is never above what he or she writes about. Criticism needs space for it to be developed, space for ideas to be explained and contextualised.

Recommended Links :

- [Vídeo] Interview with Fernando Trueba at he Instituto Cervantes in Dublin by Alfonso Fernández Cid.