“By the age of 14 I had travelled the breadth of Spain from Santander to Jerez”

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our sixth guest, Tim Willcox, is a famous British journalist and Chief Presenter for BBC World News.

Willcox is probably one of the most recognisable presenters on BBC and is a regular face covering some of the major international events. He has anchored live on air include the death of Slobodan Milosevic, Kashmir earthquake, July 7 bombings, Boxing Day Tsunami and Beslan school siege. He is probably most recognisable for presenting the BBC’s live coverage from Chile during events surrounding the Copiapó mining accident and anchoring the BBC’s live daytime coverage during the early days of the Cairo January 2011 Egyptian revolution.

Willcox read Spanish at Durham University and is a passionate Hispanophile who has travelled widely in Spain and South America. He says to those who would like to learn it: «Do! Go for it. Fantastic people, food and culture!»

– How is life in the newsroom under the current global pandemic?

The BBC studios are at New Broadcasting House, Langham Place W1A 1AA (as in the hideously accurate comedy series of the same name). With 6 TV studios , 36 radio studios, 60 Edit and Graphics suites it is the largest broadcast centre in the world, and the biggest newsroom in Europe. Usually it is heaving with journalists and producers, cramming the meeting rooms, canteens and communal areas, and queueing for the big glass lifts that shoot between floors. Since lockdown the newsroom is practically empty, and run by a skeleton staff. Social distancing tape stripes the floor, and areas are blocked off as if one were working in a gigantic urban maze. Staircases are now designated Up or Down, and only one person is allowed to use the lifts. Many people are now working from home – less easy if you’re presenting TV bulletins. Everything has changed on that front as well. Presenters now do their own make-up, the studio cameras are automated, and guests are interviewed ‘down the line’ by Skype or Facetime. The brave new world.

– Most of us watched your live coverage of the rescue of the Chilean miners. How do you remember that coverage?

Vividly. Even 10 years later. And for many reasons. I wasn’t the first choice to go. I got a rushed call from my Editor while having a lunchtime swim in London. Did I speak Spanish? Could I get the next flight to Chile – another presenter had pulled out – to cover what was shaping up to be an extraordinary race against time? My producer and I landed in Santiago the next day to discover that our satellite dish and other key equipment had been diverted to Buenos Aires. So we took the connecting flight to Copiapo – with no luggage except a small camera. On board I noticed an empty seat by the Chilean Mining Minister Laurence Golborne and grabbed it. He was the man in charge of the rescue operation and was to become the most popular politician in Chile.

When we arrived at the San Jose Copper and Gold mine it was dawn in a heavy Camanchaca (freezing mist). A few tents containing some shivering relations of some of the miners were huddled near the mine’s entrance. Fires were being lit, and tea boiled. We were some of the first journalists there. Over the days and weeks we chatted and filmed – sometimes in my broken Spanish (which often caused guffaws of laughter when I used a word in Castellano that had a much saltier meaning in Chilean slang.) These families, wives and girlfriends grew to trust us, and told their remarkable stories. As did the rescue drilling teams and the politicians. There was no certainty that all the miners would survive. They and we knew that. There was constant fear that at any moment some or all of the men might die.

This huddle of tents and people grew voraciously into Camp Hope with its own canteen and school. The San Jose mine and the small town of Copiapo was to be their and our home for many weeks.

Within a fortnight the world’s media had descended. Car parks for hundreds of press mobile homes were bulldozed out of the rock. The Chilean authorities had erected large screens to show the whole rescue operation involving the tiny Fenix rescue capsule that would winch them 700 metres to safety. It started just before midnight and the most moving moment for me was watching the first man out Florencio Avalos. His young son was standing with his mother near President Pinera. As the Fenix capsule broke the surface, he wept and howled with emotion as he caught sight of his father for the first time in 69 days. Everyone cried that day – even journalists going live on air.

– Which other coverage has been important for you?

Every story has been important for numerous reasons. Rwanda for the sheer barbarity and horror of what had happened combined with the stoicism of its people. The Palestinian Intifada for the palpable rage in the West Bank and Gaza. The death of Diana for the sense of national and international shock that consumed so many millions of us at the time. Cities like Baghdad I remember for the internally bombed out buildings still standing like the cardboard tubes of used fireworks, and New York obviously for 9/11. These stories, like the Arab Spring coverage in Egypt and Libya, and the revolution in Ukraine, the tsunami in Japan and typhoons in the Philippines, plus all the hideous terror attacks around the world are also seared into my memory for the sense of physical exhaustion associated with live TV coverage. There aren’t many hotels still standing after natural disasters.

– You studied Spanish at University and became fluent. How was the learning process? Who were your Professors?

Fluent? Ojala…My love of Spain began at school and an inspirational teacher who arranged cultural / hedonistic trips. By the age of 14 I had run in the San Fermin bull festival, and travelled the breadth of Spain from Santander to Jerez. I had also listened to a lot of Albeniz, Falla and Granados. My favourite book at the time was Laurie Lee’s As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning about his journey through Spain. In my year off between school and university I retraced his journey, busking with my trumpet, and walking and hitching my way from north to south. Laurie Lee ended up near Algeciras. I completed my journey in Jerez de la Frontera where I found a temporary job as a guide at Sandeman Bodegas. At Durham university I was not a diligent student – for which I still feel shame – but I did put on productions, including Lorca’s Yerma in Spanish, and somehow get a degree. Largely thanks to the brilliant and charismatic teaching of Professor MacPherson, and Drs Dan Rodgers, Suso Ruiz and Chris Perriam who gave me a passion for Golden Age drama.

– How important is being fluent in Spanish for your journalism?

As explained it is hardly fluent. But it is useful to be able to communicate with people in their own language, and to understand their culture and national identity. It allows me to share and hopefully relate to the viewers what the characters in the story are really feeling about the events they are caught up in.

– Can you share a memory of your last news coverage in Spain?

The last story I covered in Spain was the general election. But I had been going backwards and forwards before that to Barcelona to cover the Catalan crisis. My vivid memory of that time were the huge rallies taking over the city and the drama of the declaration of independence. Sometimes we rented the large roof terrace of a stunning apartment on the Passeig de Gracia to get the best panoramic live position. Guests – both pro and anti independence were brought up to me to be interviewed. And the debates continued long after we came off air – as each side refused to change their positions.

– What would you say to someone who is thinking about learning Spanish?

Do. Go for it. Fantastic people, food and culture. And a language spoken all over the world which often opens doors. I remember meeting the Spanish Ambassador in Baghdad and after chatting away in Castellano was invited to lunch. He had the only supply of La Ina in Iraq.

– What are your favourite Spanish dishes and restaurants?

I’m basically an omnivore.

In Madrid the wonderful Ordago Restaurant near Las Ventas, also LaKasa (brilliant) and Carlos Tertiere for the best tapas and service.

In Segovia cochinillo of course at Jose Maria. Cordero asado in Pedraza always with Pedro at El Soportal.

In Barcelona – Can Colleretes. In Cadaques Compartir – for frogs legs and apple sauce. Jerez – La Tasa and Bar Juanito.

In London – it has to be Javier’s Hispania. Everything you can dream of and more….

Instituto Cervantes in London celebrates World Book Day with the reading of ‘10 Poems of Love and A Confined Song’

Instituto Cervantes in London joins the World Book Day celebrations with a reading of ’10 Poems of Love and A Confined Song’ by founder and Artistic Director of the Cervantes Theatre, Jorge de Juan. He will be joined by singer María de Juan and the event joins the list of celebrations for the 2020 Cervantine Week. It will be a week of multiple online initiatives based on all aspects of culture from books, libraries and bookstores to the publishing world, and it is open to everyone to join in and celebrate.

Having just released their new album ‘24/7’, Jorge de Juan and María de Juan come together tonight from their current locations of London and Granada, respectively. Jorge will read poems by Alfonsina Storni, Pablo Neruda, Carmen Conde, Joan Margarit and Luis García Montero among others, whilst María will sing a poem by Mario Benedetti accompanied (from Seville), by Andrés Barrios – pianist and composer who fuses world music in combination, such as flamenco and jazz. In addition, the video transmission will include photos of the journalist Jorge Pastor Sánchez, taken in Granada under the state of alarm in March 2020. The Cervantes Theatre, in collaboration with the Instituto Cervantes in London, hosts this soirée as a message of love and unity during this global pandemic.

The director of Instituto Cervantes in London, Ignacio Peyró, underlined the importance of celebrating World Book Day and Sant Jordi: “Normally on a day like today, we would be giving roses and books at our centre and celebrating reading, literature and ‘The Quixote’. This year is different, but we have made an extraordinary effort so that, although they are not face-to-face and even though they are more modest this year, our cultural activities continue to have variety and quality. In other words, they offer new, relevant and curated content by us”.

2020 Cervantine Week

Instituto Cervantes offers multiple cultural initiatives open to the public in the framework of the celebration of World Book Day, today April 23rd. With meetings with writers such as Lorenzo Silva, Elvira Lindo and Isabel Coixet, free audiobooks, the opinions and talks of more than 70 outstanding professionals in the world of culture and readings of passages from ‘Don Quixote’, among others.

The range of online projects offered today is epitomised by the verse title of the 2019 Cervantes Award winner, Joan Margarit: ‘Freedom is a bookstore’. The Cervantine Week aims to bring home, at this stage of confinement, the best of our book culture as well as promote reading and the celebration of authors, publishers and booksellers.

Even though the Instituto Cervantes in London was forced to close in response to the British government guidelines on COVID-19, our mission and cultural programmes continue online.

The Best Spanish Short Films with CinemaAttic

Every Monday, CinemaAttic and Instituto Cervantes in London, Manchester and Leeds share a weekly programme of ‘Seven Essential Short Films of the Last Decade of Spanish Cinema’. The whole thing is entirely free and accessible with English subtitles. The program is available until Sunday on both the CinemaAttic website and the Facebook event where you can also vote for your favourite shorts and comment. In addition, every Sunday at 1pm, we end the week together with ‘A Vermouth with CinemaAttic’: an online event on Facebook where a selection of the short films’ directors are interviewed.

Visual Arts: Amalgama 2020 Program

Amalgama is the first cultural initiative dedicated to promoting the work of Ibero-American female artists in the United Kingdom and will run from April to June. Amalgama, in collaboration with Instituto Cervantes in London, proposes a series of videos to present its 2020-2021 programme.

Amalgama aims to strengthen the relationship between the British public and the international art scene regarding the work of female artists from Latin America, Spain and Portugal. This year’s programme will include two exhibitions (a group show and a solo exhibition) displaying the artists’ research on the tension between nature and culture in the digital age.

The exhibitions include 15 artists, ranging from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Spain, Portugal and Venezuela. Each artist included in the final product was specially selected from the 190 applicants in an open call. For the second show, Amalgama will present the work of renowned Colombian artist Maria Elvira Escallon who was nominated for the Luis Caballero Prize in 2019.

Spanish Cinema Snippets with Joana Granero

Also available are a series of short introductions to Spanish cinema. They include presentations across a wide array of subjects, hosted by Joana Granero, Director and Founder of the London Spanish Film Festival. Each one focuses on a specific new or archival film on the work and career of leading names in Spanish cinema as well as artistic movements and schools.

In session one, Granero talks about José Luis Cuerda; filmmaker, screenwriter and producer. In session two, she will talk about a successful case: ESCAC. ESCAC, Escola Superior de Cinema i Audiovisuals de Catalunya, where teamwork and crossing barriers are primary guidelines. They have produced some of the most interesting and fresh productions over the last few years.

Literary podcasts with The Eye of Hispanic American Culture

April’s literary podcasts are produced by The Eye of Hispanic American Culture and led by Enrique Záttara who is responsible for the project. They include central figures such as the Spanish poet, professor and director of Instituto Cervantes, Luis García Montero and the Argentine novelist Mariana Enríquez.

The Eye of Hispanic American Culture is a multimedia, international and bilingual cultural project, based in London. Its objective is to promote the Hispanic-American culture residing in Europe and across the globe by connecting and informing artists, writers and intellectuals.

Great Spanish and Ibero-American composers season

Additionally, the Iberian & Latin American Music Society (ILAMS) and Instituto Cervantes in London present a series of podcasts which bring the life and work of the most representative Spanish and Ibero-American composers to life. The podcasts are released on a monthly basis and celebrate the rich musical tradition of our countries.

Ray Picot, concert reviewer at ILAMS and writer of a popular monthly column for Echoes Magazine, will focus on the masterpieces of Enrique Granados, who was one of a triumvirate of great Spanish composers to achieve international acclaim during the early 20th century.

El Instituto Cervantes de Londres celebra el Día del Libro con la lectura de ‘10 poemas de amor y una canción confinada’

El Instituto Cervantes de Londres se suma a las celebraciones del Día Internacional del Libro con una lectura de ‘10 Poemas de amor y una canción confinada’, a cargo del fundador y Director Artístico del Cervantes Theatre, Jorge de Juan, y la cantante María de Juan, que se engloban dentro de La Semana Cervantina 2020, con numerosas iniciativas culturales por internet relacionadas con el libro, las bibliotecas, las librerías y el mundo editorial, abiertas a la participación de todos.

Jorge de Juan y María de Juan, que acaba de publicar su disco 24/7, se unen en la distancia, desde Londres y Granada, respectivamente; él leyendo poemas de Alfonsina Storni, Pablo Neruda, Carmen Conde, Joan Margarit y Luis García Montero, entre otros, y ella cantando un poema de Mario Benedetti acompañada desde Sevilla, por Andrés Barrios, pianista y compositor que fusiona músicas del mundo, como el flamenco y el jazz. Además, el vídeo incluye fotos cedidas por el periodista Jorge Pastor Sánchez, tomadas en Granada bajo el estado de alarma, en marzo de 2020. Es una velada propuesta por el Cervantes Theatre de Londres, en colaboración con el Instituto Cervantes Londres, un mensaje de amor en los tiempos del virus.

El director del Instituto Cervantes de Londres, Ignacio Peyró, destacó la importancia de la celebración del Día del Libro y de Sant Jordi: “Normalmente un día como hoy estaríamos repartiendo rosas y libros en el centro y celebrando la lectura, la literatura y ‘El Quijote’. Este año es distinto, pero hemos hecho un esfuerzo extraordinario, para que, aunque no sean presenciales y aunque sean más modestas, nuestras actividades culturales sigan teniendo variedad y calidad. Es decir, que ofrezcan contenidos novedosos, relevantes y curados por nosotros mismos”.

Semana Cervantina 2020

El Instituto Cervantes ofrece múltiples iniciativas culturales abiertas a la participación en el marco de la celebración del Día Internacional del Libro, hoy 23 de abril, con encuentros con escritores como Lorenzo Silva, Elvira Lindo e Isabel Coixet, audiolibros gratuitos, opiniones de más de 70 profesionales destacados de la cultura y lecturas de pasajes del Quijote, entre otros.

Este abanico de proyectos en línea en el marco del Día Internacional del Libro y englobados bajo el lema general La libertad es una librería, título de un verso del último premio Cervantes, Joan Margarit. La Semana Cervantina pretende acercar a los hogares, en esta etapa de confinamiento, la mejor cultura del libro, contribuir al fomento de la lectura y promocionar a autores, editores y libreros.

Desde el cierre del Instituto Cervantes de Londres, en respuesta a la alerta sanitaria provocada por el coronavirus COVID-19 y siguiendo las directrices de las autoridades británicas y españolas, el programa cultural del centro ha pasado a ser en línea.

Los mejores cortometrajes con CinemaAttic

Cada lunes, CinemaAttic y los Institutos Cervantes de Londres, Mánchester y Leeds comparten un programa semanal con ‘Siete Cortometrajes Básicos de la Historia Moderna del Cine Español’, en abierto y con subtítulos en inglés. El programa está disponible hasta el domingo en la web de CinemaAttic y en el evento de Facebook donde también se puede votar por vuestros cortos favoritos y comentar de manera interactiva. ️Además, todos los domingos a la 1pm, terminamos la semana juntos con ‘Un Vermut con CinemaAttic’, evento online en Facebook donde se entrevistará a algunos de los directores de las películas.

Artes Visuales: Programa Amalgama 2020

A lo largo de los meses de abril, mayo y junio, Amalgama, la primera iniciativa cultural dedicada a promover el trabajo de mujeres artistas iberoamericanas en el Reino Unido, con la colaboración del Instituto Cervantes de Londres, propone un ciclo de vídeos de presentación del programa Amalgama 2020-2021.

El programa de Amalgama tiene como objetivo fortalecer la relación del público británico y la escena artística internacional por el trabajo de mujeres artistas de América Latina, España y Portugal. El programa de este año comprenderá dos exposiciones, una colectiva y otra individual, en las que las artistas analizarán la tensión entre la naturaleza, la cultura y los cuerpos en la era digital.

La exposición colectiva contará con el trabajo de 15 artistas de Argentina, Brasil, Chile, Colombia, España, Portugal y Venezuela, seleccionadas de las 190 candidaturas recibidas en esta primera convocatoria. La exposición individual estará dedicada a la obra de la reconocida artista colombiana María Elvira Escalón, recientemente seleccionada para el prestigioso premio Luis Caballero, en Colombia.

Píldoras de cine español con Joana Granero

A lo largo de los meses de abril, mayo y junio, en jueves alternos, el Instituto Cervantes de Londres publicará vídeo presentaciones a cargo de Joana Granero, directora del Festival de Cine Español de Londres. Cada una de ellas se centra en contenidos relativos a películas recientes y de archivo, en la obra y trayectoria profesional de destacados nombres del cine español, movimientos artísticos y escuelas.

En la primera sesión se recordará la figura de José Luis Cuerda, quien fue más que un director de cine, un guionista y un productor. Por su parte, en la segunda sesión se tratará un caso de éxito: ESCAC. La escuela de cine de Barcelona, además de ofrecer cursos con un lado práctico importante, ha producido algunas de las películas españolas recientes más interesantes.

Podcasts literarios con El Ojo de la Cultura Hispanoamericana

Los podcasts literarios del mes de abril, producidos por El Ojo de la Cultura Hispanoamericana, tienen como figuras centrales al poeta español, catedrático y director del Instituto Cervantes, Luis García Montero y a la novelista argentina Mariana Enríquez, conducidos por Enrique Záttara, responsable del proyecto.

El Ojo de la Cultura Hispanoamericana es un proyecto cultural multimedia, internacional y bilingüe, con base en Londres. Su objetivo es dar a conocer, difundir y conectar entre sí a los artistas, escritores, intelectuales y promotores de cultura de origen hispanoamericano residentes en Europa y el mundo.

Ciclo Grandes compositores españoles e iberoamericanos

Además, la Sociedad de Música Ibérica y Latinoamericana (ILAMS) y el Instituto Cervantes de Londres presentan un ciclo de podcasts que, a modo de guía de audición, y con periodicidad mensual, acercan la vida y obra de alguno de los compositores españoles e iberoamericanos más representativos de la tradición musical de nuestros países.

Ray Picot, crítico de conciertos en la Sociedad de Música Ibérica y Latinoamericana (ILAMS) desde 2001 y escritor de una columna mensual en la revista Echoes, resaltará las obras maestras clave de Enrique Granados, uno de los grandes compositores españoles, que alcanzó el reconocimiento internacional durante los primeros años del siglo XX.

“There’s much talent in Spanish film industry and now it’s being channeled”

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our fifth guest, Joana Granero, is the director of the London Spanish Film Festival in London.

Granero was born in Tarragona (Catalonia). After graduating in Law from the University of Barcelona she spent a couple of years in Italy and then moved to London, where she worked in publishing and got a MSc in Political and Social Theory from Birkbeck College.

Out of a passion for cinema Granero created the London Spanish Film Festival in 2005, an event that was to fill a gap in London’s cultural panorama by bringing contemporary Spanish cinema in a well-defined context.

In 2008 the Ambassador of Spain in London awarded her with the civil merit medal (Orden de Isabel la Católica) in recognition of her work with Spanish cinema. Granero also works as an independent curator and producer.

– Out of a passion for cinema, you created the London Spanish Film Festival in 2005, how did the idea come up?

The idea came up seeing the few opportunities to watch Spanish cinema in the UK, particularly in London, a city so rich culturally, where it was possible to watch such a wide variety of films, from so many different countries. Spain was underrepresented. Then it was only possible to watch a few films at the international festivals and only Almodóvar, Amenábar and Medem got distribution of their films with few exceptions. I thought there was so much more to watch and, having always been a cinephile, I missed it. Hence at the moment in my career in which I was looking for a change, I put myself to work and here we are!

– How have these 15 years at the LSFF been?

All in all, they’ve been exciting and enriching. They’ve been exciting because it’s never been boring or plain. We’ve lived many challenges, stressful situations alternated with moments of jubilation seeing the happiness of an audience, moments of joy with a full house and an impressed guest from Spain. Also some embarrassing and uncomfortable situations, like having to announce a guest’s last minute cancellation to an expectant audience. But every year we feel enriched with all the films, their contexts and conversations with guests, following the work of young and not so young filmmakers, and we feel extremely happy and proud to share it with audiences.

– Could you share with us a couple of anecdotes that you remember from all these years?

One of my favourite moments ever is when Jorge Coira came to present his film «18 comidas«. We introduced it briefly to a full or nearly full house, which was surprising because he was not one of the best-known directors. We went for dinner while the audience watched the film and came back to do the Q&A and as people were leaving the cinema so many were approaching him to thank him for the film and tell him how much they had enjoyed it. In English, in Spanish and in Galician. Some were even thanking me for having brought the film over. Coira was moved. I was moved and trying not to cry. It was magical. That feeling of having gifted something that had made people happy even if only for an evening.

There have been many great moments behind the scenes too, like having very informal drinks at the end of the evening in the salons of the cinema with Fernando Trueba or Javier Cámara, the Festival’s team and the projectionist. Also some delightful surprise, like when Geraldine Chaplin was our guest and a gorgeous Oona Chaplin came looking for her mother, when Olga Kurylenko came to see her friend Jordi Mollà, who was our guest, or when we spotted among our audience Mike Lee, Steve Buscemi or Elle Macpherson.

© PopKlik

– How do you describe the general picture of Spanish cinema in the UK? Do you think our film industry is in good shape?

Since we started, the position of Spanish cinema in the UK has improved generally because there have been more films distributed and home cinema and streaming have contributed to this but there is still much room for improvement. Nevertheless we are very happy to see that the Festival and its Spring Weekend have become a regular, solid and anticipated window to the cinema from Spain in London.

As per the health of our film industry, I think more should be done in terms of promotion and distribution but of one thing we are convinced: there’s much talent in Spain and it’s being channeled.

© PopKlik

– You are now working on the round off the 16th edition of the festival, what do you plan on showcasing?

It’s difficult to say anything about the next edition due to all the uncertainty surrounding COVID19 and public gatherings. We keep working in a program but we’ll have to see what is possible and what is not. So far our 10th Spring Weekend scheduled for May has had to be cancelled but we may be able to have a short «summer weekend». We have to wait a bit and see. But we keep working with the cinemas and our supporters towards a solution.

– The audience loves your Q&A featuring very diverse guests in the programme. Who would you like to have in the next upcoming months?

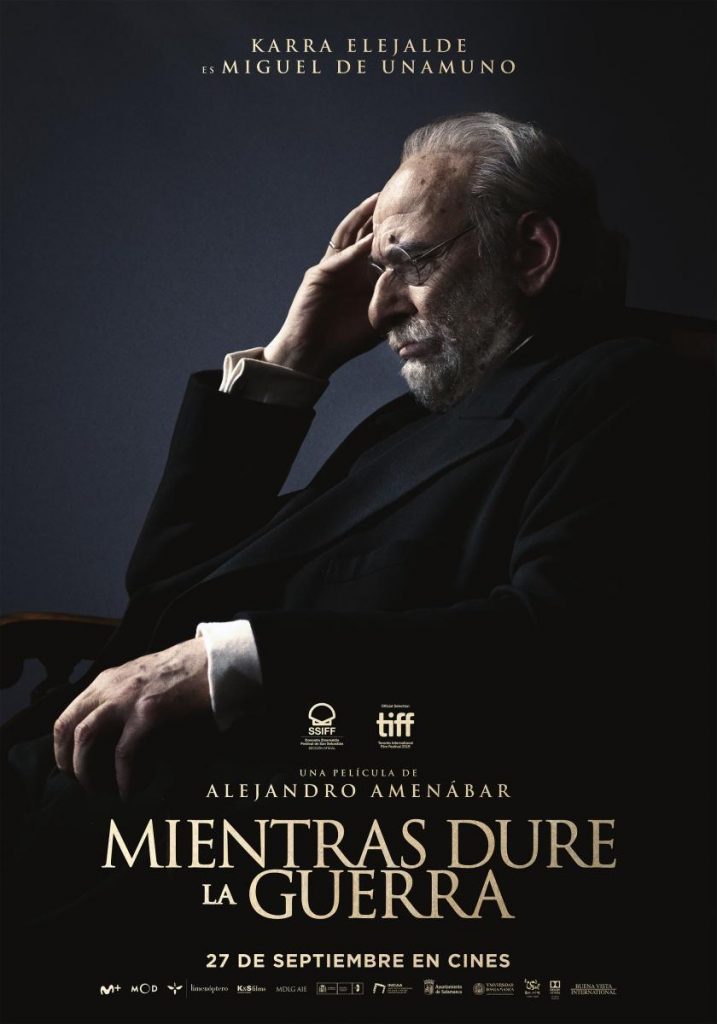

Hard to say without a program in hand but we’ve recently watched the latest film by Alejandro Amenabar, Mientras dure la guerra / While at War, and we’d very much like having him with us to talk about this film and his work as filmmaker but also about his music work. We’d love to have back Carlos Saura but this time with his daughter, Anna Saura, who has been producing his latest theater and film productions. I first met her when she was 9 years old and she’s become a great and determined producer. We’d also love having back Alvaro Longoria to talk about his tireless work as a director and producer.

Dream guest would be Pedro Almodovar. We’ve featured some of his work along the years and we’d love having him with us to talk about anything. He has so much to offer. We’d also like to talk cinema with Alberto Rodriguez. And books, films and food with Isabel Coixet. I could go on for a good while….

– Could you suggest the title of 5 Spanish films to our audience so they can get a good introduction to Spanish cinema?

As I’ve mentioned Pedro Almodovar, I’d start with Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. I think there’s a before and an after that film. At the time it came out I could not get tired of watching it. I was completely fascinated by that refreshing way of looking at cinema and at women. And I think it has a timeless quality about it.

La tia Tula, by Miguel Picazo, illustrates very well with its realist approach provincial society in 60s Spain and it’s been a point of reference for Almodovar himself.

El extraño viaje, by Fernando Fernán Gomez, is one of my favorites. It is illustrative of the very Spanish tradition of esperpento. It’s fun. It’s crazy. It’s daring. It’s absurd. One can’t but wonder how it went through Franco’s censorship in 1964.

Te doy mis ojos, by Iciar Bollain, is another gem I think with two fantastic actors, Luis Tosar and Laia Marull. In a realistic and delicate way shows a dark side of Spain’s society.

Que Dios nos perdone / May God Save us is a film by Rodrigo Sorogoyen, from a younger generation. I think it is a terribly good film and representative of a maturity in Spanish cinema.

These are only a few of the many, many films I think could provide with a good introduction to Spanish cinema. This is perhaps just one of many ways to start.

“Me encanta cómo en España la gente es bastante paciente cuando estás aprendiendo la lengua”

Esta semana continuamos con la serie de entrevistas a personalidades del ámbito hispano-británico. Nuestro cuarto invitado, Xavier Bray, es un historiador del arte especializado en arte y escultura españolas. Es, además, el actual director de The Wallace Collection en Londres.

Previamente, Dr. Bray ostentó el título de comisario jefe de la Dulwich Picture Gallery y comisario adjunto de la colección de pinturas europeas de los siglos XVII y XVIII de la National Gallery de Londres. Además, ha sido comisario de diversas exposiciones tales como Lo sagrado hecho real: escultura y pintura españolas 1600 – 1700, Goya: retratos (2015) y, más recientemente, Ribera: arte de violencia (2018) .

Bray completó su tesis doctoral en 1999, titulada «Comisiones reales religiosas como propaganda política en la España de Carlos III«, en el Trinity College de Dublín.

– Durante los últimos cinco años, has trabajado como director de la Wallace Collection, ¿podrías resumir esta experiencia para nuestra audiencia?

La Wallace Collection es una colección increíble. Es uno de los mejores museos del mundo, con una impresionante diversidad de obras de arte, desde pintura y escultura hasta porcelana. Para mí, personalmente, ha sido una gran oportunidad el poder aprender sobre diferentes tipos de arte, sobre todo porque mi especialidad es solo la pintura barroca. He tenido un equipo de comisarios muy buenos, un equipo pequeño pero muy dinámico. Además, supongo que lo que estoy intentando hacer es convertir la Wallace Collection en un lugar que todo el mundo pueda disfrutar. Esa es nuestra misión más importante y nos estaba yendo bastante bien, hasta el inicio de la cuarentena.

– Eres un famoso especialista en arte de los siglos XVII y XVIII, por el cual es famosa la Wallace Collection. ¿Podríamos decir que estáis hechos el uno para el otro?

Es verdad que, cuando era estudiante, venía a analizar las colecciones de pintura, especialmente las de pintura española, francesa e italiana. Y entonces, por supuesto, realicé mi doctorado sobre Goya y la Wallace Collection es el lugar perfecto para estudiar pintores franceses del siglo XVIII. Te encuentras rodeado de Watteau, Boucher, Fragonard, Delacroix, Dolaroche y Meissonier. Es como volver al hogar que tan bien conocía. Es como si estuviéramos hechos el uno para el otro, pero a la vez, soy consciente de que quiero hacer más con otros tipos de arte e implicarme con diversas disciplinas, investigadores y técnicas. Pero, sí, por supuesto que ha sido una experiencia muy positiva trabajar en una colección tan rica y diversa.

¿Cómo se convirtió en especialista del Siglo de Oro español?

Mi padre trabajaba como periodista para el Wallace Street Journal en Madrid. Yo tenía alrededor de 14 años en ese momento. Desgraciadamente, yo me encontraba en un internado en Inglaterra mientras mis padres estaban pasándoselo genial en el Madrid de los 80, una gran década para España. Volví durante las vacaciones para pasar un tiempo en Madrid y El Prado fue el primer museo que descubrí. Allí encontré a Velázquez, Zurbarán, y después, al gran Goya. La verdad es que acercarme a la obra de éste, me ponía muy nervioso ya que le consideraba un artista complejo y difícil. Era muy variado, creando bellas pinturas de la vida de Madrid en sus cartones, pero a la vez tenía sus Pinturas Negras, que son el más perturbador testimonio de la humanidad fracasando.

– Habla un español excelente, ¿podría contarnos un poco más sobre cómo lo aprendió?

Aprendí español cuando tenía 16 o 17 años, en Inglaterra. Por suerte, mis padres estaban en Madrid y yo me esforzaba por practicarlo cuando estaba allí. Me encanta cómo en España la gente es bastante paciente cuando estás aprendiendo la lengua y no tienen problema en ayudarte. En España es realmente fácil sumergirse en la cultura, la tradición, las gentes, la propia lengua, la literatura, etc. También viví en Granada durante un año sabático. Simplemente el estar allí, vivir la vida y conocer a todo tipo de personas de diferentes círculos enriqueció realmente mi experiencia. El mejor consejo para estudiantes de lengua española es pasar en España el mayor tiempo posible.

– Usted dirigió el programa de conservación del Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao. ¿Cuáles son tus recuerdos de esa época ahora que estás en Londres?

Siempre he tenido especial afecto por Bilbao y este museo. Es un museo maravilloso de Bellas Artes. En aquellos días, trabajé para Miguel Zugaza. Allí trabajé mucho, gracias a él, pero también tuve la gran oportunidad de trabajar en un museo europeo y trabajar con una colección que incluyó a los grandes maestros además de una colección de pintura vasca del siglo XIX. Allí había un fuerte sentimiento de identidad nacional. Lo recuerdo con aprecio, me trae muy buenos recuerdos y siempre estoy pensando en formas de trabajar con el Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao.

– Usted tiene fama de apostar por la experimentación y de tomar riesgos en tu trabajo como comisario, ¿cómo puso este aspecto en práctica en la Wallace Collection?

Comisariar y organizar exhibiciones es algo que me apasiona. No me gusta repetir cosas y siempre intentaré impulsar las exposiciones y probar ideas nuevas, tratando de aportar nuevas perspectivas o artistas o períodos. Siempre trato de hacer más vital una exposición, aportando algo relevante en relación con aquello que esté ocurriendo en el presente. La exposición más reciente en la Wallace Collection, que en teoría sigue expuesta, es la primera muestra de obras de pintores indios encargada por oficiales de la East India Company, lo que supone un área de arte sin precedentes, nunca antes considerada.

– Nos acordamos especialmente de cómo rastreó la trayectoria de Goya desde sus principios en la corte de Carlos III en Madrid hasta sus años finales en Burdeos. ¿Cómo recuerda esta exposición?

Era una exposición de los retratos de Goya y no era tan obvio realizarla contando la historia de su vida a través de los retratos de gente que le habría conocido. Fue una de esas experiencias maravillosas. Reuniendo todos los amigos de Goya, así como reinas y políticos, pudimos reconstruir su vida de una manera muy diferente. No era sobre cómo Goya se veía a sí mismo, sino sobre las impresiones de personas que conoció y las conexiones que tuvo. Y, de repente, el resultado fue la capacidad de ver a Goya de una manera muy diferente. Y, para mí, y espero que para los visitantes también, fue una experiencia extraordinaria el entender los círculos en los que se movió y sus amistades; tienes la oportunidad de conocer a este hombre extraordinario y a su alma. Es raro poder hacer eso con un artista. Fue una experiencia muy satisfactoria y me hubiera gustado poder estar allí por la noche, para oír sus conversaciones. Fue una de esas exposiciones dinámicas, donde podrías esperar que los cuadros comenzaran a hablar.

La crisis del Covid-19 ha provocado el cierre de todos los museos. ¿Habéis lanzado algún programa en línea en la Wallace Collection para este periodo especial?

Por supuesto, como todo museo, queremos asegurarnos de no desaparecer. Estamos muy preocupados de que todo el mundo se esté centrando en muchas otras cosas, lo cual está bien, pero el mayor problema es cómo conseguir que un museo como la Wallace Collection siga siendo relevante hoy en día. Estamos lanzando una serie de temas digitales con los que la gente puede involucrarse en nuestra página web. Tengo la esperanza de, si acudir al lugar del trabajo es posible, volver a la galería y realizar una grabación en directo sobre la exhibición Indian Animals. Además, esperamos poder reabrir pronto y continuar con nuestro programa. Tenemos una exposición sobre Rubens dentro de poco que reúne dos de sus grandes paisajes por primera vez. Uno es Paisaje con arcoíris (de la Wallace Collection) que yo creo que se ha vuelto más emotivo que nunca en los últimos meses. El arcoíris se ha convertido un símbolo de esperanza en Reino Unido y del gran trabajo del NHS, así que espero que este cuadro tenga un fuerte impacto en nuestra sociedad como una imagen de supervivencia y creatividad. En realidad, este es un gran momento para la creatividad.

Traducción: Blanca Gomez Garcia

“I love that in Spain, people are quite patient when you are learning the language”

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our fourth guest, Xavier Bray, is an Art Historian specialising in Spanish art and sculpture. He is the current Director of the Wallace Collection in London.

Formerly, Dr Bray held the title of Chief Curator at the Dulwich Picture Gallery and Assistant Curator of 17th and 18th-century European paintings at the National Gallery, London. Furthermore, he has curated several exhibitions including The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Sculpture and Painting 1600-1700 (2009), Goya: The Portraits (2015) and, most recently, Ribera: Art of Violence (2018).

Dr Bray completed his PhD in 1999, (entitled, ‘Royal Religious Commissions as Political Propaganda in Spain under Charles III’) at Trinity College, Dublin.

– For the past five years, you have been the director of the Wallace Collection, could you summarise this experience for our audience?

The Wallace Collection is an unbelievable collection. It’s a world class museum, with such an incredible diversity of works of art, ranging from paintings and sculpture to porcelain. For me personally, it’s been a great opportunity to learn about the different arts, particularly as I am a specialist only in Baroque painting. I have a team of very good curators, it is a small team but very dynamic. And I suppose that what I am trying to do is to make the Wallace Collection a place for everyone to enjoy. That’s our most important mission and we were doing quite well, until the lockdown.

– You are a renowned specialist in 17th- and 18th-century art, for which the Wallace Collection is famous, could we say it is a perfect match?

It’s true that when I was a student I came to study the painting collections, particularly the Spanish, the French and the Italian. And then, of course, I did my PhD on Goya and the Wallace Collection is the perfect place to study the 18th-century French painters. You’re among the likes of Watteau, Boucher, Fragonard, Delacroix, Delaroche and Meissonier. It was like returning to a home that I knew well. It’s the perfect match, but at the same time, I am very aware of wanting to do more with the other arts and engage with different kinds of disciplines, scholars and techniques. But, yes of course it has been a very happy experience to work in such a rich and diverse collection.

– How did you become a specialist in Spanish Golden Age art?

My father was a journalist working for the Wall Street Journal in Madrid. I was about 15 at that time. Unfortunately, I was set to boarding school in England while my parents were having a great time in Madrid in the 1980s, a great decade for Spain. I came back for the holidays, to spend time in Madrid and the Prado was the first museum I discovered. There I found Velázquez, Zurbarán, and then, the great Goya, who I was actually very nervous of approaching, because I found him a very complicated and difficult artist. He was so mixed; simultaneously creating beautiful paintings of Madrid life in his cartoons and alongside the Black Paintings, which are the most disturbing testimonies of humanity going wrong.

– You speak Spanish excellently, could you tell me a bit more about it?

I learnt it when I was about 16 or 17 whilst in England. Luckily, my parents were in Madrid and I tried to practice it hard when I was there. I love that in Spain, people are quite patient when you are learning the language, and they help you out. It is very immersive in Spain, you can immerse in the tradition, with people, the language itself, the literature, etc. I also took a year off and I lived in Granada. It was just being there and living life and meeting all kinds of people from different circles that really enriched my experience. The best advice to students of the Spanish language is to spend as much time in Spain as possible.

– You lead the curatorial programme at the Museo de Bellas Artes in Bilbao. What are your memories of that time now that you are in London?

I have always been very fond of Bilbao and the museum there. It’s a great museum of Fine Arts. In those days, I worked with Miguel Zugaza. I learnt so much there, thanks to him, but I also had the great opportunity of working in a European museum, and to work with a collection which included old masters as well as a great collection of Basque paintings of the 19th-century. There was a strong national identity there. I remember it fondly, of good memories and I am always thinking of new ways to work with the museum of Fine Arts in Bilbao.

– You have a reputation for experimentation and risk-taking in curating, how did you put it into practice at the Wallace Collection?

Curating and organising exhibitions is something that I love. I do not like to repeat things and will always push exhibitions forward and try out new ideas, try to bring in a new angle or an artist or a period. I always try to make it pivotal for the exhibition to try to say something relevant as to what is going on at that moment in time. The most recent exhibition at the Wallace Collection, which in theory it is still on, is the first UK exhibition of works by Indian master painters commissioned by East India Company officials, and this is an unprecedented area of art, never before even considered.

– We especially remember how you traced Goya’s career from his early beginnings at the court of Charles III in Madrid, through to his final years in Bordeaux. How do you remember this exhibition?

It was an exhibition on Goya’s portraits and it was not an obvious one to do, to tell the story of his life through the portraits of people he would have known. It was one of those amazing experiences. By bringing in all of Goya’s friends, Queens and politicians, we were able to reconstruct his life in a very different way. It wasn’t about how Goya saw himself but about the impressions of him from people he knew and the connections he had. And suddenly, the result was an ability to see Goya in a very different way. And for me, and I hope for the visitors too, it was an extraordinary experience to understand the circles in which he moved and his friendships; you get to know this extraordinary man and his soul. It’s rare to be able to do that with an artist. It was a very satisfying experience and I wish I would have been there at night, to listen to their conversations. It was one of those vibrant exhibitions where you might expect the pictures to start talking.

– The covid-19 crisis has closed all the museums. Have you launched any online programmes at the Wallace Collection for this special period?

Of course, like every museum, we want to make sure that we don’t just disappear. We are very worried that everyone is fixating on so many other things, which is quite right, but the big thing is how to keep a museum like the Wallace Collection relevant today. We are launching a series of digital themes that people can engage with on our website. I am hoping, if commuting is possible, to go back to the gallery and do a live recording of the Indian Animals exhibition. Additionally, we hope to reopen soon and carry on with our programme. We have Rubens coming up, reuniting two of his great landscapes for the first time. One of them is The Rainbow Landscape (The Wallace Collection) which I feel has become more poignant than ever in the last few months. The rainbow has become a symbol of hope in the UK and of the great work of the NHS, so I am hoping that this painting will have a really strong impact on our society as a painting of survival and creativity. This is actually a great moment for creativity.

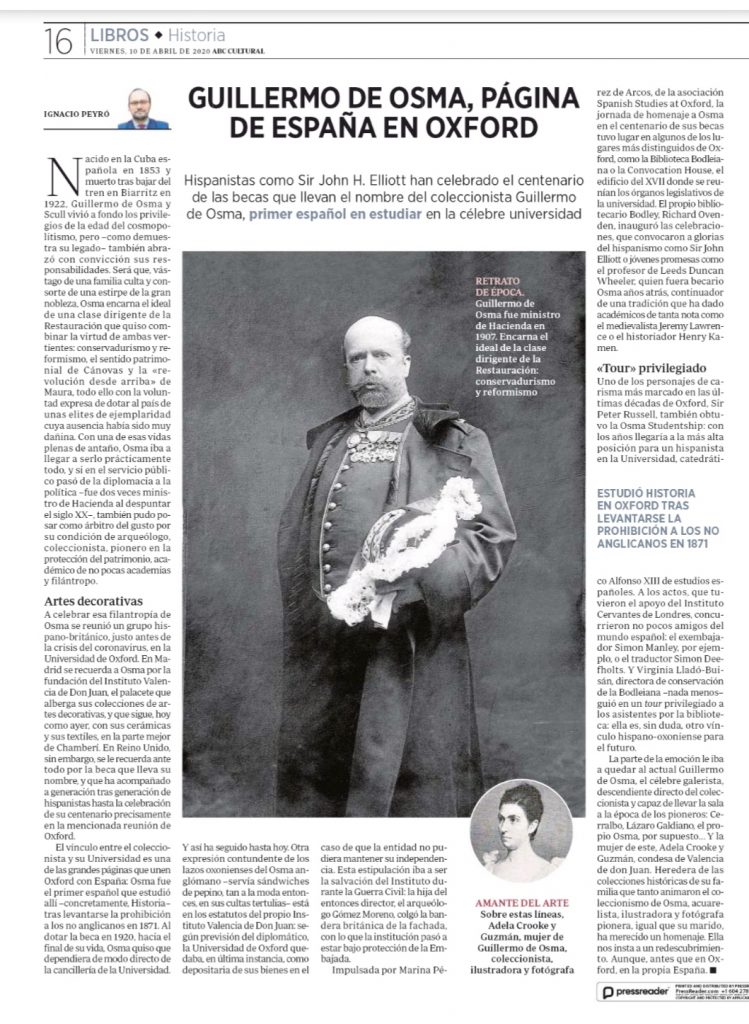

Guillermo de Osma: una página de España en Oxford

Hispanistas como Sir John Elliott han celebrado en Oxford el centenario de las becas del coleccionista Guillermo de Osma, primer español en estudiar en la célebre Universidad tras permitirse el acceso a católicos en 1871.

Ignacio Peyró, director del Instituto Cervantes de Londres.

Nacido en la Cuba española en 1853 y muerto tras bajar del tren en Biarritz en 1922, Guillermo de Osma y Scull vivió a fondo los privilegios de la edad del cosmopolitismo pero -como demuestra su legado- también abrazó con convicción sus responsabilidades. Será que, vástago de una familia culta y consorte de una estirpe de la gran nobleza, Osma encarna el ideal de una clase dirigente de la Restauración que quiso combinar la virtud de ambas vertientes: conservadurismo y reformismo, el sentido patrimonial de Cánovas y la “revolución desde arriba” de Maura, todo ello con la voluntad expresa de dotar al país de unas elites de ejemplaridad cuya ausencia había sido muy dañina. Con una de esas vidas plenas de antaño, Osma iba a llegar a serlo prácticamente todo, y si en el servicio público pasó de la diplomacia a la política -fue dos veces ministro de Hacienda al despuntar el siglo XX-, también pudo posar como árbitro del gusto por su condición de arqueólogo, coleccionista, pionero en la protección del patrimonio, académico de no pocas academias y filántropo.

A celebrar esa filantropía de Osma se reunió un grupo hispano-británico, justo antes de la crisis del coronavirus, en la Universidad de Oxford. En Madrid se recuerda a Osma por la fundación del Instituto Valencia de Don Juan, el palacete que alberga sus colecciones de artes decorativas y que sigue, hoy como ayer, con sus cerámicas y sus textiles, en la parte mejor de Chamberí. En Reino Unido, sin embargo, se le recuerda ante todo por la beca que lleva su nombre, y que ha acompañado a generación tras generación de hispanistas hasta la celebración de su centenario precisamente en la mencionada reunión de Oxford.

El vínculo entre el coleccionista y su Universidad es una de las grandes páginas que unen a Oxford con España: Osma fue el primer español que estudió allí -concretamente, Historia- tras levantarse la prohibición a los no anglicanos en 1871. Al dotar la beca en 1920, hacia el final de su vida, Osma quiso que dependiera de modo directo de la cancillería de la Universidad. Y así ha seguido hasta hoy. Otra expresión contundente de los lazos oxonienses del Osma anglómano -servía sándwiches de pepino, tan a la moda entonces, en sus cultas tertulias- está en los estatutos del propio Instituto Valencia de Don Juan: según previsión del diplomático, la Universidad de Oxford quedaba, en última instancia, como depositaria de sus bienes en el caso de que la entidad no pudiera mantener su independencia. Esta estipulación iba a ser la salvación del Instituto durante la Guerra Civil: la hija del entonces director, el arqueólogo Gómez Moreno, colgó la bandera británica de la fachada, con lo que la institución pasó a estar bajo protección de la Embajada.

Impulsada por Marina Pérez de Arcos, de la asociación Spanish Studies at Oxford, la jornada de homenaje a Osma en el centenario de sus becas tuvo lugar en algunos de los lugares más distinguidos de Oxford, como la Biblioteca Bodleiana o Convocation House, el edificio del XVII donde se reunían los órganos legislativos de la universidad. El propio bibliotecario Bodley, Richard Ovenden, inauguró las celebraciones, que convocaron a glorias del hispanismo como Sir John Elliott o jóvenes promesas como el profesor de Leeds Duncan Wheeler, quien fuera becario Osma años atrás, continuador de una tradición que ha dado académicos de tanta nota como el medievalista Jeremy Lawrence o el historiador Henry Kamen. Uno de los personajes de carisma más marcado en las últimas décadas de Oxford, Sir Peter Russell, también obtuvo la Osma Studentship: con los años llegaría a la más alta posición para un hispanista en la Universidad, catedrático Alfonso XIII de estudios españoles. A los actos, que tuvieron el apoyo del Instituto Cervantes de Londres, concurrieron no pocos amigos del mundo español: el exembajador Simon Manley, por ejemplo, o el traductor Simon Deefholts. Y Virginia Lladó-Buisán, directora de conservación de la Bodleiana -nada menos- guio en un tour privilegiado a los asistentes por la biblioteca: ella es, sin duda, otro vínculo hispano-oxoniense para el futuro.

La parte de la emoción le iba a quedar al actual Guillermo de Osma, el célebre galerista, descendiente directo del coleccionista y capaz de llevar a la sala a la época de los pioneros: Cerralbo, Lázaro Galdiano, el propio Osma, por supuesto… y la mujer de este, Adela Crooke y Guzmán, condesa de Valencia de don Juan. Heredera de las colecciones históricas de su familia que tanto animaron el coleccionismo de Osma, acuarelista, ilustradora y fotógrafa pionera, igual que su marido ha merecido un homenaje, ella nos insta a un redescubrimiento. Aunque, antes que en Oxford, en la propia España.

«British architects have great respect for the Spanish and the knowledge they bring to their practices»

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our third guest, Gonzalo Herrero Delicado, is an architect, curator and writer based in London. He is Curator of the Architecture Department at the Royal Academy of Arts (RA) where he works on a wide range of projects including exhibitions, displays and talks around architecture and its connection to wider visual arts, technology and design.

Herrero Delicado curated the opening programme for RA’s Architecture Studio Invisible Landscapes (2018-2019), a series of commissioned installations exploring how digital technologies are transforming our everyday lives and environments. Furthermore, last year he worked on a major show titled Eco-Visionaries, exploring the ecological impact of human action on the environment through modern art, architecture and design practices.

Previously, Herrero Delicado held other curatorial positions at The Architecture Foundation and the Design Museum, both in London. At The Architecture Foundation he was the curator of the institution’s public programme which included the Architecture on Film, organised in partnership with the Barbican. At The Design Museum, he managed the curation of a number of commissioned installations as part of the museum’s opening exhibition Fear and Love: Reactions to a Complex World (2016-2017).

As an architect, he worked for several practices, amongst them Lacaton & Vassal Architectes in Paris.

– You have been at the Royal Academy of Arts for almost four years, how do you find it balances with your life?

The balance is very positive and enriching, although it comes with lots of work. My university training is as an architect, and it was through practice that I trained as a curator. I studied at the University of Alicante where the training was very extensive, as well as the range of references that we handled. It was a very humanistic training that made me understand the complexity of architecture and its intimate connection with other disciplines. However, the job of curator involves many other skills that I had to learn on my own. I started as a curator of public programs at The Architecture Foundation in London. Afterwards, I went through the Design Museum and now the Royal Academy. I have gradually focused on exhibitions, which has allowed me to learn about museography little by little as well as organisation and management of exhibitions, conservation, loans, interpretation and everything that goes with being a curator in a museum.

The gradual advance in the scale and complexity of the institutions has also been very positive in this training. I organised my first exhibition on my own as a curator, editor and designer. A great leap compared to the almost 500 people who work directly and indirectly at the Royal Academy. Even so, the feeling is very familiar and we all know each other by name, which makes work and the day-to-day much easier.

– How did Eco-Visionaries, the last exhibition you curated, come about?

Eco-Visionaries was the result of a collaboration with several European museums, including Laboral in Gijón and Matadero in Madrid. A transnational exhibition that explored how artists, architects and designers are reflecting on climate change to propose alternative ways of relating between humans and the environment. Eco-Visionaries has been a great opportunity for both the museum and me personally. When I did the interview for this position, I presented a proposal on the anthropocene, and four years later I was able to organise this exhibition – together with Mariana Pestana and Pedro Gadanho. Eco-Visionaries sought to make the public reflect on the impact of our lives in the current environmental crisis. It is something that interests me a lot as a curator, making people reflect on the aspects of our life and the world around us that would otherwise go unnoticed.

– What did this exhibition mean and what impact did it have on you?

Eco-Visionaries attracted the youngest audience out of our exhibitions in recent years and that is tremendously important, particularly when it comes to climate change. It has also been an occasion to redefine our sustainability strategy and generate procedures with a lower environmental impact, something that we want to implement throughout our future program. Regarding this topic, there is still a lot to do. It continues to be an important part of my agenda, either giving talks or collaborating with different projects and foundations such as The Royal Foundation of the Dukes of Cambridge, whom I currently advise with the Earthshot Prize, which is considered the most prestigious award in environmental matters.

– You were 27 years old when you came to London and started working as a curator. How has this experience in the British capital been?

I love London. It is a city in continuous movement and has a frenetic rhythm with events and cultural plans every afternoon of the week. That’s something you can’t find in many other cities. It is something that hooks me, although sometimes it can be exhausting and I understand that it does not work for everyone. Many people come and go in this city, they do not just connect with it and prefer to live in smaller and more relaxed cities. I think that if you do not know how to make the most of the opportunities that the city offers, it is better to look elsewhere, but London can be very demanding and end up devouring you.

– The coronavirus crisis has stopped everything, but what projects are you working on that you can tell us about?

This moment is truly unique. I have had many years without having the time to dedicate myself to research and write. I am taking advantage of this time to advance various projects both inside and outside the Royal Academy. These are very eclectic in both format and theme, ranging from architecture to technology, fashion, and climate change. For example, I have spent several years researching how virtual technologies are transforming architecture and art. In 2017, I started with the Invisible Landscapes project that lasted almost a year and gave rise to a series of installations, a debate program and even a short film in virtual reality. Now I am interested in continuing this exploration and addressing how digital technologies, from social networks to biometrics, are altering and redefining the conventions of our human appreciation of beauty and the spaces dedicated to it.

– What impact does Spanish architecture have in the United Kingdom and vice versa?

In London and the United Kingdom, in general, there are many Spanish architects who work in the main studios. Some also have established their own offices here. The crisis in Spain between 2008 and 2014 had a strong impact. Specially on the real estate sector and therefore, on architects and many of them decided to settle here. English architects have great respect for the Spanish and the knowledge they bring to their practices. Likewise, many others have decided to dedicate themselves to teaching and, in practically all universities with architecture studies, you can find Spanish teachers.

– Most of our readers are Spanish students. Is Spanish spoken at the Royal Academy? And to what extent in the architectural sector?

There are several Spaniards in the Royal Academy, especially in the exhibition department. There are always conversations in Spanish in the hallways and we even had a potato omelette contest. The Royal Academy has always had a connection and appreciation for Spain throughout its history. For example, in 1920 there was an exhibition dedicated to Spanish painting with works by El Greco, Velázquez, Zurbarán and Goya among others, and whose selection was made by a committee chaired by the Duke of Alba. More recently we have had other exhibitions with Spanish artists such as Dalí / Duchamp (2017-2018) and Picasso and Paper (2020). Regarding architecture, one of the last collaborations with Spanish architects was the installation of Home (Act I) with the Barcelona studio MAIO which I curated as part of the Invisible Landscapes project that the Architecture Studio inaugurated and which is currently part of an exhibition in Matadero in Madrid. Additionally, we even had a Honorary Royal Academician, the Spanish architect Josep Lluís Sert.

– As an architect, what recommendations do you make for everyone who visits or even lives in London?

Without a doubt, a key visit is the house-museum of the neoclassical architect Sir John Soane in Bloomsbury, which keeps his incredible collection of drawings, paintings and antiques. Nearby is the Barbican, one of the most spectacular brutalist residential complexes built after the war. Another project that I always recommend to any architect who visits the city is the Snowdon Aviary at the London Zoo, one of the few buildings still standing by the visionary Cedric Price, and that can be seen perfectly from the canal without paying the entrance.

“Los arquitectos británicos tienen mucho respeto por los españoles y el conocimiento que aportan a sus estudios”

Esta semana continuamos una serie de entrevistas con personalidades de la esfera hispano-británica. Nuestro tercer invitado, Gonzalo Herrero Delicado, es arquitecto, comisario y escritor radicado en Londres. Actualmente es Comisario de Arquitectura de la Royal Academy of Arts (RA) desde donde desarrolla un amplio número de proyectos que incluyen exposiciones, instalaciones y programas públicos en la intersección entre arquitectura y las artes visuales.

Herrero Delicado fue el comisario del programa de exposiciones Invisible Landscapes (2018-2019) que inauguró el nuevo Architecture Studio y exploraba el impacto de las tecnologías digitales en nuestras vidas y entornos cercanos. Además, el año pasado trabajó en la exposición titulada Eco-Visionaries, sobre el impacto ecológico de la acción humana en el medio ambiente a través de prácticas contemporáneas en arte, arquitectura y diseño.

Previamente, Herrero Delicado trabajó como comisario en distintas instituciones, entre ellas The Architecture Foundation y el Design Museum, ambos en Londres. Fue comisario de programas públicos en The Architecture Foundation donde comisarió el programa Architecture on Film organizado junto al Barbican. Con el Design Museum se encargó del comisariado de distintas instalaciones ad-hoc para la exposición Fear and Love: Reactions to a Complex World (2016-2017) que inauguró el museo.

Como arquitecto, Herrero Delicado ha trabajado para distintos estudios internacionales, entre los que destaca Lacaton & Vassal Architectes en París.

(c) Agnese Sanvito

– Lleva casi cuatro años en la Royal Academy of Arts, ¿qué balance hace?

El balance es muy positivo y enriquecedor, aunque no falto de mucho trabajo. Mi formación universitaria es como arquitecto, y fue a través de la práctica que me formé como comisario. Estudié en la Universidad de Alicante donde la formación era muy amplia, así como el abanico de referencias que manejábamos. Fue una formación muy humanística que me hizo entender la complejidad de la arquitectura y su íntima conexión con otras disciplinas. Sin embargo, el trabajo de comisario implica muchos otros conocimientos que tuve que aprender por mi cuenta. Empecé como comisario de programas públicos en The Architecture Foundation en Londres y tras pasar por el Design Museum y ahora la Royal Academy, he ido gradualmente centrándome en exposiciones, lo que me ha permitido aprender poco a poco sobre museografía, organización y gestión de exposiciones, conservación, préstamos, interpretación y todo lo que conlleva ser comisario en un museo.

El avance gradual en la escala y complejidad de las instituciones también ha sido muy positivo en esta formación. Mi primera exposición la organicé por mi cuenta haciendo de comisario, montador y diseñador. Un gran salto comparado con las casi 500 personas que trabajan directa e indirectamente en la Royal Academy. Aun así la sensación es muy familiar y todos nos conocemos por el nombre, lo cual facilita mucho el trabajo y el día a día.

– ¿Cómo surgió Eco-Visionaries, la última exposición que ha comisariado?

Eco-Visionaries fue el resultado de una colaboración con varios museos europeos, entre los que se incluyen Laboral en Gijón y Matadero en Madrid. Una muestra transnacional que exploraba cómo artistas, arquitectos y diseñadores están reflexionando sobre el cambio climático para proponer modos alternativos de relación entre los humanos y el medio ambiente. Eco-Visionaries ha supuesto una gran oportunidad tanto para el museo como para mi personalmente. Cuando hice la entrevista para este puesto presente una propuesta sobre el antropoceno, y cuatro años después he podido organizar esta exposición – junto a Mariana Pestana y Pedro Gadanho -. Eco-Visionaries buscaba hacer reflexionar al público sobre el impacto de nuestras vidas en la actual crisis medioambiental. Eso es algo que me interesa mucho como comisario, hacer reflexionar a la gente sobre aspectos de nuestra vida y el mundo que nos rodea que de otra manera pasarían desapercibidos.

– ¿Qué significó y qué impacto tuvo para usted esta exposición?

Eco-Visionaries ha sido una de las exposiciones con más visitantes jóvenes de los últimos años y eso es tremendamente importante, en particular cuando hablamos de cambio climático. Ha sido también una ocasión para redefinir nuestra estrategia de sostenibilidad y generar exposiciones con un menor impacto medioambiental, algo que queremos implantar en todo nuestro futuro programa. En cuanto a este tema aún queda muchísimo por hacer. Sigue siendo una parte importante de mi agenda, ya sea dando charlas o colaborando con diferentes proyectos y fundaciones como The Royal Foundation de los Duques de Cambridge, a quienes actualmente asesoro con el Earthshot Prize, el cual está considerado el premio más prestigioso en materia medioambiental.

– Tenía 27 años cuando llegó a Londres y empezó a trabajar como comisario, ¿cómo está siendo esta experiencia en la capital británica?

Londres me encanta. Es una ciudad en continuo movimiento y tiene un ritmo frenético con eventos y planes culturales todas las tardes de la semana. Eso es algo que no puedes encontrar en muchas otras ciudades. Eso es algo que a mi me engancha, aunque a veces puede ser agotador y entiendo que no funcione para todo el mundo. Mucha gente va y viene en esta ciudad, no acaban de conectar con ella y prefieren vivir en ciudades más pequeñas y relajadas. Creo que si no sabes exprimir y aprovechar al máximo las oportunidades que ofrece la ciudad, es mejor buscar otro sitio, sino Londres puede ser muy exigente y acabar devorándote.

– El coronavirus ha parado todo, pero ¿en qué proyectos está trabajando que nos pueda adelantar?

Este momento es realmente único. Llevaba muchos años sin tener tiempo para dedicarme a investigar y escribir. Estoy aprovechando este tiempo para avanzar varios proyectos tanto dentro y fuera de la Royal Academy. Estos son muy eclécticos tanto en formato como en temática y van desde arquitectura a tecnología, moda o cambio climático. Por ejemplo, llevo varios años investigando sobre como las tecnologías virtuales están transformando la arquitectura y el arte. En 2017 comencé con el proyecto Invisible Landscapes que duró casi un año y dió pie a una serie de instalaciones, un programa de debates e incluso un corto en realidad virtual. Ahora me interesa seguir esa exploración y abordar cómo las tecnologías digitales, desde redes sociales a biometría, están alterando y redefiniendo las convenciones de la belleza humana y los espacios dedicados a ella.

– ¿Qué impacto tiene la arquitectura española en Reino Unido y viceversa?

En Londres y el Reino Unido en general viven muchísimos arquitectos españoles que trabajan en los principales estudios del país y algunos también han establecido aquí sus oficinas propias. La crisis en España entre 2008 y 2014 tuvo un fuerte impacto sobre todo en el sector inmobiliario y por tanto en arquitectos, los cuales muchos de ellos decidieron establecerse aquí. Los arquitectos ingleses tienen mucho respeto por los españoles y el conocimiento que aportan a sus estudios. Así mismo, muchos otros han decidido dedicarse a la docencia y en prácticamente todas las universidades con estudios de arquitectura se pueden encontrar docentes españoles.

– La mayoría de nuestros lectores son estudiantes de español. ¿Se habla español en la Royal Academy? ¿Y hasta qué punto en el sector arquitectónico?

Somos varios españoles en la Royal Academy, sobre todo en el departamento de exposiciones. Siempre hay conversaciones en español en los pasillos y hasta hemos tenido algún concurso de tortilla de patata. La Royal Academy siempre ha tenido una conexión y apreciación por España a lo largo de su historia. Por ejemplo, en 1920 hubo una exposición dedicada a la pintura española con obras de El Greco, Velázquez, Zurbarán y Goya entre otros, y cuya selección fue realizada por un comité presidido por el entonces Duque de Alba. Más recientemente hemos tenido otras exposiciones con artistas españoles como Dalí / Duchamp (2017-2018) y Picasso and Paper (2020). En cuanto a arquitectura, una de las últimas colaboraciones con arquitectos españoles fue la instalación que Home (Act I) del estudio barcelonés MAIO que comisarié como parte del proyecto Invisible Landscapes que inauguró el Architecture Studio y que actualmente forma parte de una exposición en Matadero en Madrid. Además, incluso tuvimos un Honorary Royal Academician, el arquitecto español Josep Lluís Sert.

– Como arquitecto, ¿qué recomendaciones hace para todo aquel que visita o vive en Londres?

Sin duda una visita clave es la casa-museo del arquitecto neoclásico Sir John Soane en Bloomsbury que alberga su increíble colección de dibujos, pinturas y antigüedades. Muy cerca está el Barbican, uno de los complejos residenciales brutalistas más espectaculares construidos después de la guerra. Otro de los proyectos que recomiendo siempre a cualquier arquitecto que visita la ciudad es el Snowdon Aviary en el London Zoo, una de las pocas construcciones que siguen en pie del visionario Cedric Price, y que se puede ver perfectamente desde el canal sin necesidad de pagar la entrada.

CONVERSACIONES HISPANO-BRITÁNICAS – Jorge de Juan: “El Cervantes Theatre quiere ser parte de este nuevo renacimiento que ha de llegar”

Esta semana comenzamos una serie de entrevistas a personajes del ámbito hispano-británico. Nuestro primer invitado es Jorge de Juan, fundador y director artístico del Cervantes Theatre, quien nos contará los inicios del teatro, cómo repercute la crisis del COVID-19 en su trabajo y sus planes de futuro.

Jorge de Juan (Cartagena, 1961), actor, productor y director de cine y teatro español, se formó en la Real Escuela de Arte Dramático de Madrid y en la Asociación Británica de Teatro. Ha dirigido obras como The Public and The Grain Store (Fourth Monkey); End of the Rainbow; Dracula; The 39 Steps The Woman in Black; Bodas de Sangre, The Judge of the Divorces… and others, The House of Bernarda Alba and Yerma (STC).

Como actor, ha aparecido en más de 20 obras de teatro, 30 películas y series de televisión. Ha ganado el Premio Francisco Rabal por su papel en El Mejor de los Tiempos (1990), el Premio de Teatro Turia por su trabajo en La Mujer de Negro (1998) y su película Bala Perdida, ganó el premio a la mejor película y banda sonora en los premios Mostra de Valencia del Cine.

De Juan también fundó y abrió el Cervantes Theatre en noviembre de 2016. Es una creación de la Spanish Theatre Company (STC), una charity (organización benéfica) británica. El teatro presenta una combinación de producciones de la STC y actuaciones de obras españolas y latinoamericanas de otras compañías de teatro. Desde el Instituto de Cervantes de Londres y Acción Cultural Española (AC/E) apoyamos activamente la labor y el trabajo del Cervantes Theatre en Londres.

¿Cuáles fueron sus inicios del teatro? ¿Por qué eligió Londres?

Yo estudié teatro en Londres con 19 años. Estuve a punto de quedarme en la Royal Shakespeare Company, pero José Luis Gómez me llamó para su Edipo Rey y luego llegó Jaime Chávarri con sus Bicicletas son para el verano y regresé y me quedé en España. Mi maestro y amigo, Jorge Eines, me dijo que tenía una deuda pendiente con Londres y aquí estoy; aproveché que mandé a mi hija a estudiar aquí con 15 años y me vine para estar más cerca de ella. Junto con Paula Paz creamos la Spanish Theatre Company y empezamos a hacer Lecturas Dramatizadas en diferentes teatros. Más tarde el Council de Southwark nos puso en contacto con Network Rail por una nueva iniciativa que estaban planificando en Union Street y nos metimos en la locura de construir, sin dinero, el primer teatro de habla hispana en la historia del teatro británico y lo conseguimos, pero eso es una historia muy larga…

¿Qué momento hermoso recuerda de esta andadura?

La gente que nos ha ayudado, las caras de los espectadores cuando terminan las representaciones; colegios que vienen desde Bruselas a ver La casa de Bernarda Alba y se vuelven en el mismo día, o vuelan desde Belfast! Una mujer mayor, tras ver Yerma, llorando me dijo: «Llevo 27 años viviendo en Londres y poder vivir lo que he vivido hoy aquí con Lorca, en mi idioma, no tengo palabras, estoy realmente emocionada, por favor seguid así, ¡no desfallezcáis!”

Los alumnos con diferentes profesiones que quieren hacer teatro y que ves que les cambias la vida. Las personas que se han conocido y se han relacionado gracias a nuestras obras y nuestro teatro; la inmensa familia que se ha creado, es emocionante.

¿Cómo afecta el COVID-19 al Cervantes Theatre?

Hemos cerrado el teatro, cancelado la gira, nos hemos ido a casa y los planes que teníamos se han congelado, como es lógico, las posibles ayudas que creíamos que íbamos a tener este año desde España están en el aire junto al virus y el futuro es muy incierto. Sólo tenemos recursos para pagar dos meses el alquiler del teatro y puede que dejemos de existir. Vamos a hacer todo lo que esté en nuestras manos pero hay mucha incertidumbre.

De cualquier manera no dejo de pensar que hay mucha gente que va a perder sus trabajos, que no van a tener ni para comer, compañeros que van a sufrir un cambio radical en sus vidas, no somos los únicos y hemos de ser solidarios con todo lo que nos rodea, sólo con solidaridad se podrá salir de este golpe tan brutal e inesperado a las raíces mismas de nuestra sociedad.

Además, han tenido que cancelar la gira de La Casa de Bernarda Alba. ¿Qué dió tiempo a hacer? ¿Con qué se queda de esa gira?

Pudimos hacer Birmingham y Leeds. Nos quedaba Belfast y Bristol y estábamos en conversaciones con otros lugares ante el éxito que estábamos teniendo.

Fue espectacular ver los teatros llenos de estudiantes, de la comunidad española y de británicos amantes de la cultura española, escuchando a Lorca y reaccionando ante esta obra de una manera que me sorprendió.

Me quedo con una frase que dijeron en Leeds: “¡Gracias por venir donde nunca viene nadie con obras como esta y tener la oportunidad de disfrutarla; por favor, volved!»

El Cervantes Theatre opera como una organización benéfica, ¿qué pueden hacer los amantes del teatro en estos momentos para ayudarles?

Ahora mismo estamos pidiendo toda la ayuda que sea posible para resistir hasta que podamos volver a abrir. Ya hay algunas personas que están reaccionando, hemos recibido alguna donación y también se han dado de alta en nuestra sistema de Amigos del Teatro. No tengo palabras para agradecerlo, me conmueve saber que somos importantes para algunas personas y es por ellas y por todo el mundo que valora lo que hacemos, que seguimos con fuerzas para seguir luchando contra el virus y contra las carencias. Cualquier persona que quiera contribuir lo puede hacer a través de nuestra web www.cervantestheatre.com.

¿Qué programación esperan poder hacer el resto del año?

Teníamos planificado dedicar el año a las Spanish Golden Ages 1530-2020, hacer un recorrido por la creatividad española desde el Siglo de Oro hasta nuestros días. Era un programa que iba a durar dos años (en Noviembre del año que viene se cumplirían cinco años desde que abrimos el teatro) pero, como te puedes imaginar, ahora está en el aire. Íbamos a hacer teatro, poesía, música pero ahora, sinceramente, no sé…

¿Por qué considera que es tan importante la labor del Cervantes Theatre?

Creo que no debo ser yo quien responda a esta pregunta. Habíamos triplicado las cifras de audiencia en estos tres años y medio que llevábamos abiertos. Todo iba muy bien y la repercusión que estábamos teniendo, pese a los pocos recursos con los que contábamos, era espectacular.

Y habría que pensar en que cuando volvamos a la «normalidad», nuestro país se va a enfrentar a un reto económico y social sin precedentes, habrá que tomar medidas muy importantes internamente pero también externamente y nosotros humildemente podemos ayudar, con nuestro espacio, a comunicar esa «normalidad» en un país como el Reino Unido con tantos vínculos económicos y culturales con España y en una ciudad como Londres.

Cultura, Industria, Turismo y Exteriores deberían ser nuestros interlocutores cuando haya que poner en marcha de nuevo la maquinaria… Queremos ser parte de este nuevo renacimiento que ha de llegar y esperamos serlo.