Blog del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín

Torre Martello

Entrevista con Ana Cristina Herreros

Ana Cristina Herreros: La ratita nunca fue presumida

Entrevista con Ana Cristina Herreros realizada el 26 de mayo de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en el “Taller de técnicas de narración oral”.

Ana Cristina Herreros (Ana Griott es su nombre de batalla cuando se sube a un escenario a contar cuentos) nació en León y realizó su tesis doctoral en Madrid sobre la literatura de los que ni escriben ni leen. Así, investigando en la tradición oral, se topó con los cuentos y empezó a contar. Después comenzó a escribir: Cuentos populares del Mediterráneo, Libro de monstruos españoles, Libro de brujas españolas, La asombrosa y verdadera historia de un ratón llamado Pérez o Geografía mágica son algunos de sus libros publicados por Siruela. En 2011 publicó, también en esta editorial, Cuentos populares de la Madre Muerte.

Sergio Angulo: —Ana, ¿qué diferencia hay entre un cuento y un relato?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Normalmente los relatos tienen una estructura un poco difusa. Los cuentos tienen todos la misma estructura. Hay un planteamiento de personajes y situaciones, un conflicto, un personaje que se pone en camino, alguien que ayuda, el «donante» que diría Vladimir Propp, y el conflicto se resuelve. Y cuando el personaje que se ha puesto en camino consigue resolver el conflicto, alcanza la dignidad de rey, que quiere decir que se convierte en soberano de su propia vida. En los relatos no necesariamente existe esta estructura. Puede existir una estructura un poco distinta.

Sergio Angulo: —Segunda diferencia: ¿qué diferencia hay entre un monstruo y un villano?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Es importante atender a la etimología, que es el origen de nuestras palabras. La palabra «monstruo» viene de monstrare, del latín, que significa «enseñar», y de ahí viene la palabra «maestro» también.

El monstruo es lo que se pone delante de ti, agranda una cualidad casi siempre negativa que tú tienes dentro, y te muestra que tú también a veces eres así. Eso es un monstruo. Y un villano es, como su propio nombre indica, alguien que comete maldades, villanías, en una villa, en una ciudad.

Sergio Angulo: —Hablando de la etimología de las palabras. Cuando hablamos de «contar», ¿tiene algo que ver con contar números?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Sí, porque cuando uno cuenta establece una prioridad en el relato que va a contar y hace como una enumeración de sucesos que va desgranando, como si lo que se cuenta fueran las cuentas del rosario, una cuenta detrás de otra, o un suceso detrás de otro.

Sergio Angulo: —Otra diferencia, ¿qué diferencia hay entre un cuentacuentos y un actor?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Hay muchas diferencias. Hay una muy importante y es que el actor cuenta o hace su espectáculo de narración o de teatro con una cosa que en el lenguaje técnico teatral se llama «la cuarta pared», y es que el público es una pared, el público no interactúa. El narrador mira a los ojos de la gente que está escuchando y tiene en cuenta lo que sucede en el espectáculo. Cuando tú haces teatro miras al infinito, porque el espectador no existe. Pero cuando tú cuentas, tú miras a los ojos de cada una de las personas que hay en el teatro, aunque haya cuatrocientas personas.

Sergio Angulo: —¿Se interactúa?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Claro, porque eso es la oralidad, y en la oralidad, frente a lo escrito, lo que hay es un presente, el presente del momento, del instante en el que yo cuento. Entonces, si yo vengo aquí a contar «El bosque animado» y de pronto llegan niños muy pequeños, pues tengo que incorporar cuentos que los tengan en cuenta, porque, si no, no se va a producir el acto comunicativo que yo pretendo. Esa es una de las diferencias. Otra es que los actores tienen un texto que permanece invariable y el narrador no tiene un texto. El narrador tiene una cadena de sucesos, unas imágenes, que va contando, que va desgranando a medida que avanza su relato. Y de hecho, en la interacción con el público pueden suceder cosas como que, de pronto, algo que suceda en el público lo incorpore el narrador a su relato. En el espectáculo teatral no. El texto es el que es. Nada que suceda se puede incorporar. Actor y narrador son dos figuras completamente diferentes.

Sergio Angulo: —La última diferencia: ¿Qué diferencia hay entre Ana Cristina Herreros y Ana Griott?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Son la misma y son dos. Esto es como lo de Don Quijote, que cada vez que salía tenía un nombre distinto. Con todos mis respetos a Don Quijote y sin pretender ser Don Quijote tampoco.

Normalmente firmo con mi nombre, Ana Cristina Herreros. Como editora soy Cristina Herreros y como narradora soy Ana Griott, porque cuando empecé a contar, yo estaba haciendo una tesis doctoral y mi tesis se titulaba Neopopulismo en la lírica culta del siglo XX. Son estos títulos rimbombantes que le tiene que poner uno a la tesis para que parezca una investigación de algo serio. Y como mi tesis era sobre oralidad, me fui a escuchar a los narradores que participaban en el Festival de Otoño de Teatro en el año 92, porque en la letra pequeña del programa ponía «Espectáculo de narración oral escénica». Y me quedé absolutamente perpleja, porque había dos narradores contando con adultos, no contaban con niños, en un teatro, y la gente les aplaudía y lo que allí sucedía era una comunicación impresionante. Y yo decidí que quería hacer eso, pero mi formación era universitaria, libresca, y no tenía ninguna experiencia escénica. Entonces empecé a hacer cosas de expresión corporal, de voz, de clown también. Y todo eso me ayudó para ser la narradora en la que me convertí. Ana Cristina Herreros se había convertido en Ana Griott.

Luego empecé a contar. Por entonces gestionábamos un local de copas donde se contaba todos los martes, el Café de la Palma, en la Calle de la Palma, en Madrid. Estuvimos contando todos los martes durante once años. Como contábamos todas las semanas y el público es muy fiel, no se podía contar los mismos cuentos, pero tampoco daba tiempo a preparar cuentos nuevos de una semana a otra, de modo que nos agrupamos varios narradores y nuestro grupo se llamaba Griott. Entonces la gente empezó a decir «Ana la de Griott» y con Ana Griott me quedé. El nombre me lo pusieron. No lo elegí yo. Por cierto, que los griotts son los narradores del centro-este de África. Es el nombre genérico con el que se los designa.

Sergio Angulo: —Ahora que hablas de África: Cuando se estudian las culturas, y sobre todo culturas primigenias, se estudia lo que narran, y se suele relacionar a veces con rituales. Se cuentan historias alrededor del fuego, o por la noche para dormir a un niño. ¿Qué conexión hay entre narración y ritual?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Hay mucha conexión. Los griots acompañan a los niños que van a morir. Acompañan, en general, a la gente que va a morir, también a los niños. Tocan un instrumento que solamente tocan en esa ocasión, que se llamapluricuerda. Y lo que le cantan a los niños es «Tranquilo, niño, que tu madre está aquí, tranquilo, niño, que tu madre está allá». El objetivo del griot es que el niño muera en paz, que muera tranquilo.

Es gente, como te decía, que acompaña la vida y la muerte, porque los cuentos son para vivir. De hecho, hay un estudio en África que cuenta que en las comunidades donde las madres van a trabajar y los niños se quedan con las abuelas, los niños tienen una esperanza de vida mayor. Y eso que las abuelas no dan de comer, porque no tienen leche en sus pechos. Pero sí que dan un alimento, que es el alimento de la confianza, de la esperanza, que son los cuentos. Los niños que escuchan cuentos de sus abuelas tienen más oportunidades de sobrevivir.

Sergio Angulo: —¿Todos los cuentos tienen que tener moraleja?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —No. Lo de la moraleja es un invento del racionalismo francés y del siglo XVIII. Los cuentos tienen mensaje, no tienen moraleja, que es muy distinto. La moraleja se hace explícita, el mensaje no. El mensaje está ahí y cada cual lo interpreta según le parece. Porque el cuento es un texto literario también, aunque no tenga letra, aunque sea oral. Y como todo texto literario, es ambiguo: del mismo cuento uno puede entender una cosa y otro otra. Los cuentos no tienen moraleja, pero sí tienen mensaje, un mensaje muy profundo, y prueba de ello es que se han transmitido de generación en generación, porque entroncan con lo profundamente humano.

Si te fijas, los cuentos populares de todos los lugares son esencialmente los mismos. Los motivos folclóricos son universales, lo que cambian son los detalles. El elemento mágico en el Mediterráneo es la almendra o la naranja. En Siberia no, porque no hay. Pero los cuentos son los mismos, y es así porque los cuentos hunden sus raíces, según Vladimir Propp y el formalismo ruso, en tiempos muy antiguos, en el Neolítico, en el momento en el que hombres y mujeres comenzaron a cultivar la tierra y se convirtieron de nómadas en sedentarios. En ese momento se gestan todos los cuentos populares. Esto sucede en la zona del Cáucaso. Con las migraciones, después de la última glaciación, los cuentos se expanden por todo el mundo. Por eso los cuentos son iguales.

Sergio Angulo: —Vladimir Propp decía que no sólo los temas son universales, sino su estructura también.

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Así es, la estructura de la que hablaba antes, cuando comentaba la diferencia entre cuento y relato, es de Propp. Sí, la estructura coincide, porque los cuentos tradicionales son perfectos. No les sobra ni les falta nada. Por eso se transmiten de generación en generación.

Sergio Angulo: —Después de Vladimir Propp, Joseph Campbell, en su estudio de los mitos, también establece una universalidad total en las religiones, en sus mitos.

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Mircea Eliade también tiene unos ensayos sobre mitos universales. Estas cosas que se transmiten tienen que ver con lo profundamente humano, y en eso somos todos iguales. No hay diferencia entre norte, sur, ni siquiera entre este y oeste. Mi último libro es sobre la muerte, y aunque pueda parecer que la muerte en Occidente y en Oriente es distinta, en los cuentos populares es exactamente la misma. En Japón hay reminiscencias de cuentos populares, de fábulas, de mitos, que tienen que ver con las griegas. La cultura parece distinta, pero no lo es.

Sergio Angulo: —Sobre el mensaje en los cuentos, hay una cosa que me interesa. ¿Cómo se puede utilizar en el sistema educativo actual el contar cuentos para transmitir un mensaje?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Está sucediendo. Los cuentos son lectura obligatoria en la escuela, pero sobre todo son cuentos de autor. De hecho, los cuentos populares en el sistema escolar no tienen buena prensa porque hubo quien se empeñó en decir que transmitían valores machistas y que había que quitarlos de la escuela. Eso es no tener mucha profundidad en el conocimiento de los cuentos populares, porque los cuentos populares son perfectamente coeducativos y enseñan cosas como la convivencia.

Hay un cuento precioso que es «La niña de los tres maridos». Yo cuento una versión de Murcia, pero hay versiones por todas partes. Es una niña que se acaba casando con tres chicos, fíjate. Eso, en el cuento es supernormal, cuando la normalidad en las sociedades donde existen matrimonios múltiples es que sean poligámicas, no poliándricas. O sea, que existan diferentes mujeres y no diferentes hombres. Eso en los cuentos populares se contempla con una normalidad impresionante.

Yo cuento también el cuento de «La ratita». La rata, en la tradición oral, nunca fue presumida. Nos la volvieron presumida porque en el siglo XIX se generalizó la enseñanza, con la ley Moyano, y vinieron las órdenes religiosas, francesas sobre todo, a enseñar a las señoritas españolas. En ese momento, una «señorita» que se preciara debía ser recatada. Para inculcar que no había que ser presumidas, le dieron la vuelta al cuento y volvieron a la rata presumida. Por eso se compra un lazo. En la tradición que yo conozco, y es la versión que yo manejo, la rata se compra un repollo, bien grande, excava con los dientes y se hace un balcón. A la rata se la comen por lo que se nos comen a todas: porque elige fatal y se casa con un gato.

Sergio Angulo: —Se casa con el novio equivocado.

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Claro.

Sergio Angulo: —Para terminar, me gustaría que nos dieras un consejo. Ya hemos hablado de dónde vienen los cuentos, pero a la hora de contarlos, a la hora de narrar, cómo podemos hacerlo mejor.

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Yo creo que es importante no contar los cuentos con una finalidad, no contar los cuentos porque queremos enseñar algo, sino contar el cuento que a nosotros nos conmueva. Porque desde ahí es desde donde uno puede transmitir la pasión.

La pasión se transmite si tú la sientes, la ternura se transmite si tú la sientes, el miedo se transmite si tú lo sientes. Yo creo que es muy importante elegir aquellos cuentos que nos toquen profundamente y contar esos cuentos, porque esos son los que mejor van a llegar, los que van a ser transmitidos con la mayor eficacia. Si uno cuenta desde su propia pasión, desde su propia entraña, desde su propia emoción, es muy difícil no emocionar al que esté enfrente.

Enlaces recomendados

- [Vídeo] Entrevista realizada a Ana Cristina Herreros en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín por Sergio Angulo.

- Ana Cristina Herreros en Siruela.

- Ana Cristina Herreros en Conocer al autor.

< List of Interviews

Interview with Ana Cristina Herreros

Ana Cristina Herreros: The Little Rat Was Never Vain

Interview with Ana Cristina Herreros held on 26th May 2012 at the Dámaso Alonso Library of the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin in connection with her participation in a workshop on the “Techniques of Storytelling”.

Ana Cristina Herreros (Ana Griott is her stage name when telling stories) was born in León. She completed a thesis on folk literature in Madrid.. It was there, while researching the oral tradition of storytelling, that she discovered the many folk tales, which she started to speak and write about: Cuentos populares del Mediterráneo, Libro de monstruos españoles, Libro de brujas españolas, La asombrosa y verdadera historia de un ratón llamado Pérez, and Geografía Mágica are some of her books published by Siruela. Her most recent book, Cuentos populares de la Madre Muerte, was published in 2011.

Sergio Angulo: —Ana, what’s the difference between a story and a tale?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Usually a story has a different structure, whereas a tale always follows the same pattern. There’s a formula for characters and situations. There´s always a conflict and a character who embarks on a journey, and somebody who helps them, the “donor”, as Vladimir Propp would call it. In the end the conflict is always resolved. And when the protagonist manages to resolve the conflict, he earns the dignity of king, which means he is the master of his own life. Stories don’t necessarily have this structure. Their structure can be a little different.

Sergio Angulo: —What’s the difference between a monster and a villain?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —It’s important to pay attention to etymology, which is the origin of our words. The word “monster” comes from the Latin word “monstare”, which means “to show”. The word “master” also comes from this.

The monster you are faced with almost always embodies a negative quality that you have within yourself, and shows you that’s the way you are sometimes. That’s a monster. A villain, as the name suggests, is someone who does evil things, villainies, in a town or a city.

Sergio Angulo: —Speaking of the etymology of words. When we say “contra” (to tell/ to count), does this have anything to do with “counting” numbers?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Yes, because when you are recounting something, you establish a central theme in the story and figure out a sequence of events, as if they are rosary beads that you’re counting, one after the other.

Sergio Angulo: —What’s the difference between a storyteller and an actor?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —There are many differences. A very important one is that an actor gives a performance with using a technique called “the fourth wall” in technical theatre language. The audience doesn’t interact and so they represent a wall. A narrator looks into the eyes of his audience and takes the reaction to his performance into account. In theatre, you look into space, because the spectator doesn’t exist. When you are storytelling, you look into the eyes of each and every person in the room, even if there are four hundred people.

Sergio Angulo: —Is there any interaction?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Of course, because that is the oral tradition. As opposed to the written, you have the present, that present moment, the instant when I´m telling a story. If I came here to tell the story “The Living Forest” and there were young children, well I would have to include stories that took them into account, because otherwise there wouldn’t be the interaction I’m aiming for. That’s one of the differences. Another one is that actors have set lines, whereas a narrator doesn´t have any. The narrator has a chain of events and images he describes, as his tale advances. In fact, through the interaction with the audience things can change. If something suddenly happens in the audience, you can incorporate it into your tale. This doesn’t happen in a theatre. The lines are what they are. Nothing that happens can be included. The actor and the narrator are two completely different figures.

Sergio Angulo: —Lastly, what’s the difference between Cristina Herreros and Ana Griott?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —They are one and the same, like Don Quixote, who had a different name every time he went out. But with all due respect to Don Quixote and without pretending to be him either.

I usually sign my name Ana Cristina Herreros. As an editor I’m Cristina Herreros but as a narrator I’m Ana Griott, because when I started telling stories I was writing my doctoral thesis and the title was Neopopulismo en la lírica culta del siglo XX (Neopopulism in the Sophisicated Poetry of the 20th Century) . These are the kind of high-flown titles you have to give your thesis, so your research appears to be about something serious. As my thesis was about the oral tradition, I went to the Autumn Theatre Festival in ´92, because I noticed in the small print of the program, it read “Spectacle of Storytelling”. I was absolutely amazed, because there were two narrators in a theatre, telling stories to adults, not children, and peopled were applauding them. It was an amazing interactive experience and I decided I wanted to do that, but my background was academic and I had no experience on stage. So I started learning things about bodily expression and voice, and about being a clown as well. All of that helped me to be the narrator that I became. Ana Cristina Herreros became Ana Griott.

Soon I started telling stories. We managed a local bar called El Café de la Palma in Madrid, where there was storytelling every Tuesday. So every Tuesday, for eleven years, we told stories to the same audience, and we couldn´t tell the same stories twice. As there was no time to prepare new stories from one week to the next, we formed a group called Griott. Then people started saying “Ana from the Griott” and so I involuntarily adopted the name Ana Griott. By the way, the “Griots” are narrators from Central-East Africa. It’s the generic name that they´ve been given.

Sergio Angulo: —When studying cultures, and especially primeval cultures, you always look at what is narrated, and sometimes it’s related to rituals. Stories are told around the fire, or at night, to put a child to sleep. What’s the connection between narration and rituals?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —There is a big connection. The Griots accompany dying children. They accompany people who are dying in general, but also children. They play a stringed instrument that is only played on such an occasion. And what they sing to the children is “be calm child, your mother is here, be calm child, your mother is there”. The Griot’s goal is for the child to die in peace, to die calmly.

They are people, as I was telling you, who accompany life and death, because stories are for living. In fact, there is a study in Africa that states that in communities where the mothers work and the children stay at home with their grandmothers, children have a higher life expectancy. This is because although grandmothers don’t feed them, as they don’t have breast milk, they can still give them nourishment – the nourishment of trust, of hope, which are in these stories. The children who listen to their grandmother´s stories have a greater chance of survival.

Sergio Angulo: —Do all stories need to have a moral ending?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —No, moral endings are an invention of French Rationalism in the 18th Century. Stories have a message, not a moral, which is very different. The moral ending becomes explicit, the message doesn’t. The message is there and everyone can interpret it whichever way they want. Because the story is also a literary text, even if it’s not written down, it’s ambiguous. From the same story, one person can understand one thing and another something else. They don’t have a moral but they do have a message. They have a very profound message and proof of that is that they have been passed on from generation to generation, because they have a profoundly human connection.

If you take a look, folk tales from different places are essentially the same. Folklore motifs are universal, what changes are the details. The magical element in the Mediterranean is the almond or the orange, but in Siberia there is none. Yet the stories are essentially the same, because stories have their roots, according to Vladimir Propp and Russian formalism, in ancient times, in the Neolithic period, the moment where men and women started to cultivate the land and changed from nomads to sedentary people. All folk tales have their origin in this era, in the Caucasus zone. After the last glacial period, stories spread throughout the world with the migration of people. That’s why all stories are the same.

Sergio Angulo: —Vladimir Propp also said the structure is universal, not only the themes.

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Yes, the structure I described earlier, when differntiating between a story and a tale, is Propp’s structure. The structure stays the same because it´s perfect. There’s nothing either superfluous or lacking. That’s why they it´s passed on from generation to generation.

Sergio Angulo: —After Vladimir Propp, Joseph Campbell also established a total universality with regard to religions and myths, in his study on the topic.

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Mircea Eliade has also written essays on universal myths. The ideas that are passed on are profoundly human, which we can all relate to. There’s no difference between North and South, East and West. My last book is about death, and even though it may seem that death in the West and East is different, in folk tales it’s exactly the same. In Japan there are accounts of folk tales, of fables and myths, that are related to the Greek. The cultures may seem different, but they´re not.

Sergio Angulo: —There’s one thing that really interests me about the message in stories. How could storytelling be used in the current educational system to pass on a message?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —It’s happening, but mostly with stories that are created specifically with that in mind. In fact, folk tales don’t have good press in the school system because some people argued that folk tales transmit sexist values, and they´ve been banned from schools. This comes from not having a deep knowledge about folk tales, because folk tales are perfectly co-educational, as they teach things like coexistence.

There’s a lovely tale, I have a version from Murcia, but there are versions everywhere – the one about the girl with the three husbands. It’s a girl who ends up marrying three boys. In the story it’s completely normal, even though what’s normal in societies with multiple marriages is polygamy, not polyandry. That is to say, there are multiple wives and not multiple husbands. In folk tales that is remarkably treated as normal.

I also tell a story about the little rat. The rat was never vain in the oral version. They made her vain because in the 19th Century, education spread with the Moyano law and the religious orders came here, mostly French, to teach young Spanish ladies. At the time, being a lady meant being modest. They had to be modest. To teach them not be vain, they turned the story around and made the rat vain, so she buys a ribbon. In the tradition I know, and that’s the version I tell, the rat buys a huge cabbage and digs in with her teeth, making a ridge. In the end, the rat gets eaten for the same reason we all get eaten – she makes a terrible choice and marries a cat.

Sergio Angulo: —She marries the wrong person.

Ana Cristina Herreros: —Exactly.

Sergio Angulo: —Just to finish, I’d like to ask you for advice. We have already talked about where stories come from but, when it comes to telling them, how can we do it better?

Ana Cristina Herreros: —I think it’s important not to tell stories with a purpose, not to tell stories because we want to teach something, but to tell them because they move us. Because that’s how you can pass on the passion.

Passion and warmth is passed on if you feel it, but also fear. So I think it’s very important to choose stories that move us profoundly and to tell those stories. Because those are the ones that will reach others more effectively, that will be shared. If you speak from your own passion, from inside yourself, with your own emotion, it’s very difficult not to affect those around you.

Recommended links

- [Video] Interview with Ana Cristina Herreros at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin by Sergio Angulo.

- Ana Cristina Herreros in Siruela.

- Ana Cristina Herreros in Conocer al autor.

< List of interviews

Jesús Ruiz Mantilla en nuestra biblioteca / Jesús Ruiz Mantilla in our library

Jesús Ruiz Mantilla (Santander, 1965) nos visitó el pasado mes de noviembre y nos concedió esta entrevista que ahora os ofrecemos en video.

Jesús Ruiz Mantilla es periodista y escritor. Desde 1992 trabaja en El País. Escribe sobre música, cine y libros, temas por los que dice sentir verdadera pasión.

Ha publicado hasta ahora un libro de ensayo, Placer contra Placer (2008), y cinco novelas: Los ojos no ven (1997), con el universo de Dalí de fondo; Preludio (2004), en la que aborda la capacidad del artista para la autodestrucción; Gordo (2005), donde reivindica la obesidad sin complejos.; Yo, Farinelli, el capón (2007), en la que cuenta la biografía del más famoso “castrato” de todos los tiempos y Ahogada en llamas, publicada en marzo de 2012, novela que reúne varios géneros en uno, pero donde el aspecto histórico tiene un peso innegable.

Ahogada en llamas estará a vuestra disposición en la biblioteca a finales de este mes.

Jesus Ruiz Mantilla (Santander, 1965) visited us last November and answered to our questions in this interview.

He is journalist and writer. Since 1992, he works in EL PAIS writing about music, movies and books.

He has published an essay: Placer contra placer (2008) and five novels: Los ojos no ven (1997), with the universe of Dalí in the background, Preludio (2004), which addresses the artist’s ability to self-destruction; Gordo (2005), where he claims an obesity without complex; Yo, Farinelli, el capón (2007), which tells the biography of the most famous “castrato” of all time and Ahogada en llamas, published in March 2012, a novel that brings together various genres in one, but where the historical aspect has an undeniable weight.

Ahogada en llamas will be available in our library later this month.

El ritual de las doncellas: Audiolibro de la semana / Audiobook of the week

Descárgate ahora El ritual de las doncellas, el audiolibro que te proponemos para esta semana.

Descárgate ahora El ritual de las doncellas, el audiolibro que te proponemos para esta semana.

En esta novela, un peculiar detective del siglo XVII llamado Capablanca, junto con su inseparable ayudante Fray Hortensio, se verá envuelto en un misterio, justo cuando está a punto de embarcar rumbo hacia las Indias. Se han producido una serie de asesinatos, sus víctimas siempre son mujeres y las muertes parecen obedecer a una especie de ritual sangriento. Capablanca descubrirá que el Madrid barroco de los bajos fondos y las altas esferas del poder no están tan alejados como cabría pensar.

Su autor, José Calvo Poyato, es Catedrático de Historia y doctor por la Universidad de Granada en Historia Moderna. El final de la Casa de Austria y la llegada de los Borbones a España han constituido la parte fundamental de sus investigaciones, aunque ha transitado, con obras de divulgación, por otros momentos de nuestra Historia.

En 1995 publicó su primera novela: El hechizo del rey a la que siguieron Conjura en Madrid y La Biblia Negra. Varias de sus obras han sido traducidas a diferentes idiomas.

Como novelista le han interesado las épocas que constituyen su especialidad histórica y también las mujeres que por su personalidad llamaron la atención de sus contemporáneos, como es el caso de Caterina Sforza, protagonista de La dama del dragón e Hipatia de Alejandría, firgura principal de El Sueño de Hipatia.

Download Now El ritual de las doncellas, the audiobook that we suggest for this week.

In this novel, a quirky detective in the seventeenth century called Capablanca, along with his trusty assistant Fray Hortensio, will be wrapped in a mystery, just as he is about to embark route to America. There have been a series of murders, the victims are always women and deaths seem to obey a kind of bloody ritual.

The author, José Calvo Poyato, is Professor of History and Phd. in Modern History. The end of the Habsburg Dinasty and the arrival of the House of Bourbon in Spain have been the fundamental part of his research.

In 1995, José Calvo Poyato published his first novel El hechizo del rey which was followed by Conjura en Madrid and La Biblia negra. Several of his works have been translated into different languages.

Entrevista con Bill Richardson

Bill Richardson: Bajo una superficie que puede parecer fría, Borges es profundamente humano

Entrevista con Bill Richardson realizada el 17 de mayo de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su conferencia “Jorge Luis Borges y el sentido de la vida”.

Bill Richardson, director del Departamento de Español en la Universidad Nacional de Irlanda en Galway, ha publicado varios ensayos sobre España y América Latina, con un especial interés por la obra del autor argentino Jorge Luis Borges. Es autor de Spanish Studies: An Introduction (2001), y coautor (con Chris Ross y Begoña Sangrador-Vegas) de Contemporary Spain (3ª ed., 2008). Otras publicaciones suyas incluyen el tema de la espacialidad y las referencias deícticas en la lengua , la literatura y la traducción españolas. Su último ensayo es Borges and Space (Peter Lang, 2012).

Sergio Angulo: —Bill, ¿cuándo empezó a estudiar español?

Bill Richardson: —Bueno, en este país hay poca gente que estudia español y siempre ha habido poca gente, pero yo en cambio sí estudié el español en la escuela secundaria. Empecé a los doce o trece años. Después, a los quince años pasé seis semanas en Oviedo y me entusiasmé. Con una familia española muy acogedora, que me trató muy bien, pero que no sabía hablar inglés para nada. Entonces tuve que defenderme en español.

Sergio Angulo: —En su universidad, en su departamento ¿qué nivel de español tienen los estudiantes que llegan?

Bill Richardson: —Nosotros somos un poco como las demás universidades en Irlanda. La gran mayoría de nuestros estudiantes son principiantes. Nunca han estudiado español. El ochenta por ciento, o incluso más, empiezan desde cero. También tenemos un grupo para aquellos que han estudiado español en el colegio y han llegado a un nivel de bachillerato, lo que nosotros llamamos el Leaving cert. Pero a ese ochenta por ciento tenemos que darle un curso muy intensivo para que alcance un nivel adecuado para estudiar o incluso leer literatura, por supuesto, y para estudiar en el extranjero un año, en España o en Latinoamérica. Porque durante nuestro tercer año, los estudiantes van fuera a estudiar en España o en Latinoamérica.

Sergio Angulo: —¿Cómo es la demanda de español?

Bill Richardson: —Muy buena, de hecho. Crece cada año. Cada año hay más estudiantes que quieren estudiar español. En los últimos cinco años, el número de estudiantes que estudian en nuestro primer curso ha subido desde cien a unos doscientos cincuenta ahora. O sea que hay mucha demanda de español. Pero la mayoría son estudiantes principiantes. El francés siempre ha sido el idioma más fuerte aquí como lengua extranjera, pero ahora crece cada vez más el número de estudiantes que estudia español incluso en la escuela. Sin embargo, de momento no es comparable al número de estudiantes que habla francés.

Sergio Angulo: —Ha escrito usted artículos y libros sobre traducción y sobre literatura con un especial interés en Borges, que también fue un gran traductor. Pero él decía que a él le gustaba mejorar el original para crear otra obra. Eso no es muy común ahora.

Bill Richardson: —No está de moda ahora. Ahora se valora muchísimo el texto original, la cultura original, aún si eso crea dificultades para el lector a la hora de entender estas referencias culturales.

Lawrence Venuti, por ejemplo, asevera que no hay que homogeneizar, no hay que cambiar mucho el texto para adecuarlo al lector-meta, sino que hay que respetar el texto original. Es una forma de reconocer la importancia de la cultura original y del texto original. Pero esa no era la manera de traducir de un Borges. Él se tomaba la libertad de crear una nueva obra literaria. Si él pensaba que se mejoraba con un ligero toque aquí y allá, lo hacía siempre.

Sergio Angulo: —¿Por qué Borges?

Bill Richardson: —A mí siempre me ha interesado. En la facultad estudié la obra de Borges y me fascinó a los dieciocho años. Borges es un escritor que escribe muchas cosas: prosa, poesía y ensayos. Pero incluso los cuentos que escribe son como poesías, en el sentido de que uno siempre puede volver al cuento y encontrar más. Más significados, más riqueza, más profundidad. En ese sentido, son una fuente de riqueza y se puede volver a ellos una y otra vez. Y aún así, es imposible entender todas las referencias y los matices de significado. Un cuento borgiano es muy denso, hay muchísimo en cada párrafo.

Sergio Angulo: —Simbología también.

Bill Richardson: —Claro, por ejemplo el laberinto. Es típico de Borges. El laberinto simboliza de alguna forma la falta de conocimiento, lo que somos los humanos, imperfectos en el sentido de que no entendemos lo que es la vida que nos rodea. Él siempre consideraba, más que nada, que era un hombre perplejo, que la vida está llena de misterios muy difíciles de entender.

También hay otros símbolos. Los espejos, por ejemplo. Hay muchos espejos en Borges. El espejo es muy interesante, sobre todo desde mi punto de vista, que estudio el tema espacial. Un espejo está en el espacio, pero de alguna forma nos indica algo que parece estar en un espacio y no está ahí. Estamos mirándonos a nosotros mismos allí donde no estamos.

Es esa manera de romper la concepción de la vida que tenemos. Él es siempre subversivo en ese sentido. En los cuentos, que son como cuentos de detectives, siempre hay un toque que indica algo más, un toque metafísico. En el gran cuento de «La muerte y la brújula», por ejemplo, cada lugar del crimen que se encuentra en ese cuento parece sugerirnos algo más. Y luego está la ironía, porque Borges, aunque da la impresión de ser un hombre muy serio, y conocía muy bien toda la filosofía, de hecho es muy irónico. Juega con el lector y tiene un gran sentido del humor.

Sergio Angulo: —Escribió cuentos, ensayos y poesía, pero no escribió novela. ¿Habría sido una novela de Borges imposible de digerir, con tanto significado?

Bill Richardson: —A mí me parece que hay algo de eso. Él dijo que prefería imaginar que la novela existía y resumirla. ¿Por qué gastar doscientas o trescientas páginas diciendo algo, si de hecho se puede resumir en media docena de páginas y comentarlo? Esto es lo que llama la atención sobre Borges en el mundo moderno, esa manera de autoreflexionar sobre lo que es un cuento y sobre nuestra existencia.

Sergio Angulo: —Con todo lo que se ha escrito sobre Borges en todos los idiomas, ¿qué tiene de nuevo su libro,Borges and space?

Bill Richardson: —Lo mío es el tema del espacio. Y como dices, eso nos toca de muchas formas. Está el espacio físico, lo que es encontrar una cosa en un lugar, la ubicación física. En Borges eso se nota incluso en ese cuento que he mencionado, «La muerte y la brújula». Él juega con las ubicaciones geográficas físicas dentro de una ciudad que es Buenos Aires, aunque él no nos dice que es Buenos Aires. Luego, por otra parte, está la especulación sobre el espacio y el universo, el espacio como forma del universo. Borges también nos invita a reflexionar sobre nuestro lugar en este universo y preguntarnos: ¿este universo es infinito o no?

En cualquier caso, es maravilloso. Pensar que el universo sigue hasta el infinito es inimaginable. Por otra parte, si termina en algún lugar, ¿qué hay después? En un cuento como «La biblioteca de Babel» nos invita a especular sobre ese tipo de temas. Borges inventa esa biblioteca infinita, o casi infinita, no sabemos. Es una biblioteca que capta todos los libros que puede haber y, de alguna forma, es un símbolo otra vez del universo.

En varios capítulos de este libro he intentado ver algunos de los temas más importantes relacionados con el espacio. Estos que he mencionado son algunos de ellos. Pero también hay otros temas, por ejemplo el tema del poder.

El poder está relacionado con el dominio o la producción de un espacio. Y también está el tema de encontrar algo en el espacio. Incluso en «La biblioteca de Babel», ese cuento que he mencionado, habla de personas que son «buscadores», que van en busca de libros que pueden dar con el sentido de la vida. Eso de que en algún lugar podemos encontrar algo que sea tan especial que nos explique lo que es nuestra vida es también algo muy tentador. Y es muy humana esa añoranza de sentido, de significado. A veces la gente dice que Borges es muy inhumano, muy intelectual, muy frío. Pero de hecho, detrás de esa superficie que quizás sea fría, o da la impresión de ser fría, están todos estos temas humanos, muy humanos.

Enlaces recomendados

- [Vídeo] Entrevista realizada a Bill Richardson en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín por Sergio Angulo.

- Bill Richardson en la Universidad Nacional de Irlanda en Galway.

- Departamento de español en la Universidad Nacional de Irlanda en Galway.

Sobre Jorge Luis Borges

< Listado de entrevistas

17 de mayo: un día muy solicitado / 17th May: a very busy day

El 17 de mayo es el Día de Internet el Día contra la homofobia y la transfobia el Día Mundial del Reciclaje y, por si fuera poco, el Día das Letras Galegas, el más veterano de todos, que hoy celebra su 50 aniversario. Este año está dedicado a Valentín Paz Andrade. Felicidades a todos los gallegos, y a los que reciclan, y a los que están contra la homofobia y la transfobia, y cómo no, a todos los internautas.

El blanco círculo del miedo

El blanco círculo del miedo es la última novela del escritor Rafael Escuredo. A través de esta novela policiaca, su autor hace una dura crítica a la sociedad actual, donde el ser humano llega a tener miedo y a dudar absolutamente de todo. En la novela, se narra la historia del cruel asesinato de Claudia Morante, que trae de cabeza al inspector Sobrado y sus compañeros de la brigada criminal.

Rafael Escuredo (Estepa, Sevilla, 1944), abogado y escritor, presentó su novela en Dublín y nos concedió esta entrevista que ahora ofrecemos en video.

Rafael Escuredo fue el primer Presidente de la Junta de Andalucía. Actualmente trabaja como abogado y dirige la Fundación BLU (Fundación de literatura universal). En los últimos tiempos, ha compaginado su carrera profesional con su pasión por la escritura. Ha publicado tres novelas más: Un sueño fugitivo (Planeta, 1994), Leonor, mon amour (Almuzara, 2005), con la que ganó el Premio Andalucía de la Crítica y Te estaré esperando (Almuzara, 2009); el poemario Un mal día (Endymión, 1999), el libro de relatos Cosas de mujeres (Plaza & Janés, 2002) y un recopilatorio de sus artículos de prensa bajo el título Andalucía Irredenta (Biblioteca Nueva, 2004). Están a tu disposición en la biblioteca.

El blanco círculo del miedo is the lastest novel by writer Rafael Escuredo. This thriller makes a strong criticism of current society. A society where people are scared and doubt about everything.

This is the story of the cruel and brutal murder of Claudia Morante. A case that proves a challenge for Inspector Sobrado and his colleagues at the criminal brigade. Ignacio Lama is a young executive in the financial sector whose only interests are women and money. He is the victim’s last lover and he becomes the main suspect. His involuntary involvement in the murder precipitates events and jeopardizes his plan to blackmail the directors of the bank where he works. The brigade investigates the case in a race against time and against the backdrop of the multimillion financial debt faced by the bank and its directors.

Rafael Escuredo (Estepa, Sevilla, 1944), lawyer and writer, was the first President of the Junta de Andalucía. In recent years, he has combined his career with his passion for writing. He has published three more novels: Un sueño fugitivo (Planeta, 1994), Leonor, mon amour (Almuzara, 2005), and Te estaré esperando (Almuzara, 2009). Other work includes the collection of poems Un mal día (Endymión, 1999), short stories Cosas de mujeres (Plaza & Janés, 2002) and a compilation of his newspaper articles, Andalucía Irredenta (Biblioteca Nueva, 2004). All of them are available in our library.

Film screening: El perro del hortelano

El ciclo de cine “Un libro, una película” llega a su fin este miércoles a las seis de la tarde con la película “El perro del hortelano”.

El ciclo de cine “Un libro, una película” llega a su fin este miércoles a las seis de la tarde con la película “El perro del hortelano”.

Os ofrecemos la adaptación de una comedia palatina de Lope de Vega (1562-1635). Su título hace alusión al refrán El perro del hortelano no come ni deja comer.

Cuenta la historia de Diana, condesa de Belflor, una joven perspicaz, impulsiva e inteligente. Está enamorada de Teodoro, su secretario, pero comprueba que éste ya está comprometido con la dama Marcela. Movida por los celos y la envidia, todo su afán se centra en separar a los dos enamorados.

El autor de la obra de teatro en la que se basa la película es Lope de Vega (Madrid, 1562). Poeta, novelista y el más grande dramaturgo español. Cultivó todo tipo de géneros vigentes en su tiempo, dando además forma a la comedia. Escribió unas 1.500 obras teatrales entre las que se encuentran auténticas joyas de la literatura universal de las que se conservan 426.

Pilar Miró (Madrid, 1940) es una reconocida directora de cine española. En 1982 ocupó el cargo de Directora General de Cinematografía y entre 1986 y 1989 dirigió la Radio y Televisión Pública Española. Su actividad posterior se diversificó entre la dirección de teatro y de ópera y su carrera cinematográfica, siendo su última producción El perro del hortelano (1996).

A la proyección le seguirá un debate dirigido a todo tipo de público.

The film series “One film, one Book” ends this Wednesday at 6pm with the screening of the film “El perro del hortelano”.

Based on a comedy by Lope de Vega (1562-1635). The title refers to a Spanish saying equivalent to ‘People often grudge others what they cannot enjoy themselves’.

The story is about Diana, the Countess of Belflor, is an intelligent, impulsive woman in love with her secretary, Teodoro. He is engaged to Marcela, one of the countess’s ladies in waiting. When the countess finds out about the engagement, driven by jealousy, she does everything possible to separate the lovers.

Lope de Vega (Madrid, 1562) is the most prominent Spanish playwright. He also wrote poems and novels, exploring all literary genres of his times. Furthermore, he was one of the forerunners of the comedy. He wrote about 1500 plays, from which only 426 have been kept, representing a treasury of world literature.

Pilar Miró (Madrid, 1940) is a renowned Spanish filmmaker. In 1982 she became General Director for Filmmaking and from 1986 to 1989 she headed the Spanish Public Broadcasting. Her subsequent career diversified between theatre and opera direction and filmmaking. The dog in the Manger (1996) is her last film.

The screeening will be followed by an open discussion.

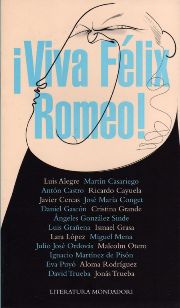

Autor del mes | Author of the month: Félix Romeo

El pasado 7 de octubre fallecía Félix Romeo. En las numerosas reacciones a su prematura y repentina muerte, con solo cuarenta y tres años, se repiten con frecuencia los encendidos elogios a su categoría humana y literaria.

El pasado 7 de octubre fallecía Félix Romeo. En las numerosas reacciones a su prematura y repentina muerte, con solo cuarenta y tres años, se repiten con frecuencia los encendidos elogios a su categoría humana y literaria.

Carismático, generoso y brillante, su obra derrocha fuerza y energía, no exenta de tintes fatalistas, como se refleja en Amarillo (2008), basado en el impacto que le produjo el suicidio de un amigo íntimo años antes.

Su personalidad polifacética combinaba sin esfuerzo su trabajo como poeta, escritor, articulista, traductor, ensayista y presentador del prestigioso programa cultural La mandrágora. Participó hasta como actor ocasional; su salida de la cárcel tras casi un año, después de ser condenado por un delito de insumisión, se reflejó en un corto de Fernando Trueba, parte del largometraje Lumière et compagnie. El director quiso plasmar su visión de la magia del nacimiento del cine a través del expresivo rostro de Romeo.

En sus otras novelas se mezclan igualmente ironía, humor y tristeza. En Dibujos animados (1994) realiza una novela fragmentaria, inspirada en Perec, que retrata su infancia en el barrio zaragozano de Las Fuentes.

Discothèque (2001) es una comedia negra y coral que mezcla la experiencia en la cárcel del autor con alusiones literarias y humor, donde caben tanto el imaginario del cine y la literatura norteamericana, como el iluminado Miguel de Molinos y el futbolista del Real Zaragoza, Nayim.

Poco antes de morir había terminado un nuevo libro, Noche de los enamorados (2012), reflexión sobre el crimen, la justicia y la libertad donde investigaba el caso de un compañero de celda en la prisión de Torrero.

En el año 2009, tuvimos el placer de acogerle con motivo de la Semana de las Letras organizada en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín. Este mes recordamos su obra en nuestra biblioteca y a través de una mesa redonda que se celebrará el próximo 29 de mayo a las 6 de la tarde en el Café Literario.

Félix Romeo died on October 7th. There were numerous reactions and praise about his excellence as a writer and human being after his early and sudden death at the age of 43.

Charismatic, generous and outstanding; his work radiates strength and energy and also a fatalistic overtone, as it was reflected in Amarillo (2008), based on how the suicide of a close friend had an impact on him.

His versatile personality combined different sides as poet, writer, columnist, translator, essayist and TV presenter of the prestigious programme La mandrágora. He even participated as an actor, after spending a year in prison due to his refusal to serve military service. He was filmed on his way out of prison in a Fernando Trueba´s short-film which is part of the film Lumière et compagnie. The director wanted to capture the magic of the birth of cinema through Romeo´s expressive face.

Irony, humour and sadness mix in his other novels as well. Dibujos animados (1994) is a fragmentary novel, inspired by Perec. It portrays his childhood in a neighbourhood in Zaragoza.

Discothèque (2001) is an ensemble and dark comedy that mixes his experiences in prison and literary and humoristic references: there is place for cinema images, North American literature, the enlightened Miguel de Molinos or the Real Zaragoza football player, Nayim.

Just a little bit before his death, he finished a new book, Noche de los enamorados (2012) , a reflection about crime, justice and freedom while he researches the case of a cell mate at Torrero prison.

We had the pleasure of having him as a guest in the Semana de las Letras organized by Instituto Cervantes Dublin in 2009. We remember his work this month at our library and also with a round-table on May 29th at 6pm in Café Literario.

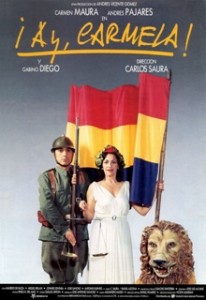

Cine / Film screening: ¡Ay, Carmela!

No olvides que este miércoles, a las seis, tienes una nueva cita en el Café Literario. Continuando con el ciclo de cine “Una película, un libro”, esta semana os ofrecemos la película ¡Ay, Carmela! que nos cuenta la historia de Carmela (valiente y espontánea), Paulino (pragmático y cobardón) y Gustavete (mudo), trovadores que actúan para el ocio del bando republicano durante la Guerra Civil Española.

No olvides que este miércoles, a las seis, tienes una nueva cita en el Café Literario. Continuando con el ciclo de cine “Una película, un libro”, esta semana os ofrecemos la película ¡Ay, Carmela! que nos cuenta la historia de Carmela (valiente y espontánea), Paulino (pragmático y cobardón) y Gustavete (mudo), trovadores que actúan para el ocio del bando republicano durante la Guerra Civil Española.

Son un grupo de cómicos que ameniza como puede a los soldados republicanos durante la Guerra Civil, pero están cansados ya de pasar penalidades en el frente. Carmela, Paulino y Gustavete se dirigen a Valencia pero, por error, van a parar a la zona nacional. Allí son hechos prisioneros, y la única manera de salvar sus vidas es ofreciendo un espectáculo para un grupo de militares nacionales que choca de lleno con la ideología de los cómicos.

El autor de la obra en la que se basa esta película es José Sanchis Sinisterra, considerado uno de los grandes renovadores del teatro español. Su obra se mueve entre la tradición y las nuevas tendencias contemporáneas, combinando narración y dinamismo teatral para implicar al espectador por completo en las obras.

Su director, Carlos Saura es un cineasta y fotógrafo español de amplio prestigio internacional. En 1992 recibió la Medalla de Oro de la Academia de las Ciencias y de las Artes Cinematográficas de España. Sus primeros trabajos se posicionan a favor de los marginados con un estilo documental. Ha sido reconocido con numerosos galardones que lo avalan por obras como La caza, Peppermint Frapé, La prima angélica, Cría cuervos…

A la proyección le seguirá un debate dirigido a todo tipo de público.

Don´t forget you appointment this Thursday at 6pm at Cafe Literario. We continue with the film series “A film, a book” with ¡Ay Carmela! a Spanish film directed in 1990 by Carlos Saura and based on the eponymous play by José Sanchís Sinisterra. The film stars Carmen Maura, Andrés Pajares, and Gabino Diego as a trio of traveling players performing for the Republic, who inadvertently find themselves on the Nationalist side during the closing months of the Spanish Civil War.

The film is based on a play by José Sanchis Sinisterra who is a Spanish playwright and theatre director. He is best known, outside of Spain, for his award-winning play, ¡Ay Carmela! His work swifts between tradition and contemporary tendencies, combining narration and the dynamism of theatre in order to involve the audience in the play.

The director is Carlos Saura, an internationally acclaimed Spanish filmmaker and photographer. In 1992 he was awarded the Golden Medal of the Spanish Academy of Sciences and Film Arts. In his first steps, he used the documentary style to raise awareness for the deprived people. Some of his films, notably La caza, Peppermint Frapé, La prima angélica and Cría cuervos have received multiple awards.

The screeening will be followed by an open discussion.

Audiolibro / Audiobook: La debutante

La protagonista de esta novela recuerda los pasos que, de la nada y a través del crimen, la llevaron a triunfar en una sociedad, en la que ser “de baja ralea y escasos posibles” no es un impedimento para hacer fortuna. A partir del reconocimiento de esta”‘verdad” indiscutible, nace, tras años y años de existencia gris y rutinaria, una heroína poco convencional.

Su autora, Lola Beccaria, es doctora en Filología Hispánica por la Universidad Complutense. Desde el año 1987 trabaja en la Real Academia Española, donde ha realizado diversos trabajos como lexicógrafa y lingüista.

Además de diversos relatos, artículos de prensa y de investigación, ha publicado seis novelas: La debutante (1996), La luna en Jorge (finalista del Premio Nadal 2001), Una mujer desnuda (Anagrama, 2004), Mariposas en la nieve (Anagrama, 2006), El arte de perder (Planeta. Premio Azorín 2009) yZero (Planeta, 2011).

La debutante es nuestro audiolibro de la semana. Lo tienes a un clic de distancia. ¡Descárgalo ya!

The protagonist of this novel recalls the steps she took to succeed in a society where being “of low birth” is not an impediment to making a fortune. Upon recognition of this “truth” without question, our unconventional heroine was born, after years of gray and routine.

The author, Lola Beccaria, a PhD in Hispanic Philology from the Complutense University, works since 1987 in the Royal Spanish Academy of Language, where she has held various jobs as a lexicographer and linguist.

In addition to various reports, press articles and research, she has published six novels: La debutante (1996), La luna en Jorge (Nadal Prize finalist 2001), Una mujer desnuda (Anagrama, 2004), Mariposas en la nieve (Anagrama , 2006), El arte de perder (Planeta. Azorin Award 2009) and Zero (Planeta, 2011).

La debutante is our audiobook of the week. It’s a click away from you. Download it now!

Kirmen Uribe en el Festival Cúirt de Literatura / Kirmen Uribe at the Cúirt International Festival

Kirmen Uribe participa esta tarde junto a Manuel Rivas en el Festival de Literatura de Cúirt.

Kirmen Uribe participa esta tarde junto a Manuel Rivas en el Festival de Literatura de Cúirt.

Kirmen Uribe, escritor, poeta y ensayista vasco, escribe sus obras en lengua vasca. La publicación en el año 2001 del libro de poemas “Bitartean heldu eskutik” (Mientras tanto dame la mano), supuso, según el crítico literario Jon Kortazar, una “revolución” dentro del ámbito de la literatura vasca. En 2009 recibió el Premio Nacional de Narrativa por su novela “Bilbao-New York-Bilbao”.

Kirmen Uribe and Manuel Rivas will participate this evening in the Cúirt International Festival.

Kirmen Uribe, Basque writer, poet and essayist writes his work in the Basque language. According to the literary critic Jon Kortazar, his work “Bitartean heldu eskutik” (Hold my hand in the meantime), published in 2001 amounted to a revolution in the Basque language. He was awarded the Spanish Literature Prize for his novel “Bilbao-New York-Bilbao” in 2009.

Interview with Manuel Rivas

Manuel Rivas: A Word is a Loaf of Bread Made Up of Light and Shadow

Interview with Manuel Rivas on the 26th April 2012 at the Dámaso Alonso Library of the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin, in association with his participation in the discussion “Literary encounter with Manuel Rivas”.

Manuel Rivas (A Coruña, 1957) is a writer, poet, essayist and journalist. Some of his works have been adapted to film. One of his best known works isButterfly’s Tongue, based on three stories from the book ¿Qué me quieres amor? (1996), for which he received the Premio Nacional for Spanish fiction. O Lápis do Carpinteiro has been published in nine countries and is, to date, the most translated book in the history of the Galician language. En salvaje compañía (In the Wilderness) and Los libros arden mal (Books Burn Badly), which won the Premio Nacional de la Crítica for Galician fiction, have also been translated into English. Todo é silencio (2010) (All is silence, Radom House, 2013) was a finalist for The Hammett Award for crime-writing. His latest novel,Las voces bajas, was published in Spain in 2012.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Manuel, in Butterfly’s tongue, the main character, Moncho, is a boy who is a bit scared on his first day of school. Do you remember this phase of your life?

Manuel Rivas: —My first school was a kind of creche and I was very young, I´d only just started to talk. I went with my sister who was a little older because my mother had to work. I remember I carried a plastic bag and, as there were so many of us, there was no place to sit. With the best intentions, one of the two sisters who brought us, sat me down on the kind of suitcase that children have for storage, and so I spent a year there sitting quietly on a suitcase. It was a kind of premonition of emigrant lineage. I sat there with my case, and one day, I opened the case and realised it was empty. There was nothing in it.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —As we´re discussing memories, do you remember when you first started writing?

Manuel Rivas: —That’s a process. I don’t think there’s a day you wake up saying, “I’m a writer”. I started to write very early, but they were just notes I made in a notebook. I called them poems. There’s even an anecdote about my godfather, who had a small typewriter and encouraged me to write. As it was a typewriter for receipts, it had a small carriage, so I thought it would be better to write poetry. That was the idea I had about poetry. But anyway, we’re talking about playing with words.

If I really had to choose a moment, I think it would have to do with listening. For me, that’s the first tool for a writer, as well as a journalist. So, if I had to say where the writer in me was born, it would be in a place of listening, which was a staircase in my maternal grandparents’ house – a country house in Galicia. It was a staircase where you could hide after you were sent to bed. You’d stay hidden in a sort of ascending wooden tunnel, while the stories the adults told would come filtering up the steps.

Álvaro Cunqueiro spoke of a group of sailors who understood the language of the sea. In a time when there were no such advanced forecasting tools, they could anticipate storms through signs and murmurs of the sea. They were called “the listeners” (os escoitas) and were rumoured to have one ear larger than the other. I think a writer also needs to have something like that – an ear, a conch shell larger than the other.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —You have always felt a passion for journalism. Do you think there is still that strong bond between journalism and literature?

Manuel Rivas: —Yes. There are a large number of people who have shared the status of being both a writer and a journalist. I think it´s good for a writer to have feelers, that grounding that a journalist needs to have – the principle of an active reality. Also, it’s necessary for a journalist to have a flare for style when it comes to writing.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —As a writer, do you have any routine, any rituals when it comes to writing?

Manuel Rivas: —No, I’m not very methodical. I think it’s a struggle when you write. Our body is a battlefield on which alternative energy struggles, the energy that always enables you to write and to overcome the moments of dejection. This erotic energy, this force of desire sometimes has to fight with what we call Thanatos.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —In your work, there are several literary genres. Do you feel any preference for one in particular?

Manuel Rivas: —I would represent it with the image of concentric circles. The topic of genres gives way to a theoretical reflection, a necessity to classify. But in the end, what exists is the mouth of literature. Either it exists or it doesn’t. You can find it in different forms, but it’s true there can be very poetic tales where the poetry vibrates. There can be texts presented as literary, but we don’t really perceive that vibration, that liveliness. We don’t see the mouth of literature opening. Sometimes, the mouth of literature opens in life, in a bus, in a bar, in a conversation or in the odd discussion.

I think the core of literature is poetic, that’s the first circle. The expression, “The secret zone of the human being”, is a need to express the enigmatic reverse of the mirror. That’s why I think that a way of detecting what defines literature is that it simultaneously reveals, works with light, and creates a new enigma, a new secret. It also has a strong resemblance to a camera obscura. In this case, the the light that enters through the small hole and is transformed, in conflict with the darkness and the shadows, represents the words. A word is a loaf of bread made up of light and shadow.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —What language do you feel more comfortable writing in?

Manuel Rivas: —I started writing literature in Galician and still do. I still write a big part of my work in Galician. It’s a first love and feels good, but it’s also true that the relationship between language is not a relationship of struggle or exclusion. When that is suggested, it has nothing to do with words or with language, it acts as another kind of manipulation. Actually, what languages want is to embrace each other. So I feel I would like to write in many languages. But in the end, the truth is that you have to master your own language, and that’s true whether you’re writing in Galician, in Spanish or in Inuit.

Marcel Proust used to say that the ideal way to write is with the feeling that you’re writing in an unknown or foreign language. In the end, the purpose of writing is to bring something into existence that wasn’t there before, like a new species. Even if it’s something that resembles a nettle growing out of a handful of dirt.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Your last book Todo é silencio is structured in two parts – Silencio amigo (Friendly Silence) and Silencio mudo (Mute Silence). I think Rosalía de Castro’s enthusiasts are delighted with that wink. Why did you choose these two titles for your novel?

Manuel Rivas: —Yes, Silencio mudo is an expression that appears in a poem by Rosalía called Follas novas. “Todo é silencio mudo soidá dolor…” There are different types of silence. We could go further and include undertones, but fundamentally, there’s a friendly silence that is a fertile silence, the silence, for example, that corresponds to each musical note, a note of silence. It’s a silence that helps you, a creative silence. On the other hand, it´s the root of literary creation.

The counterpoint is the silence that doesn’t help creativity, that isn´t fertile, but an imposed or acute silence. I remember a phrase that was written by an inquisitor when he ordered the cutting off of an Indian´s ears in the Andes. It’s a phrase I find tremendous and terribly precise. It states, “He was not docile to the reign of my voice”. I think that’s what mute silence is, the silence of totalitarian power, of the power that seeks not only to control society and wealth, but also people – to control their minds.

In the novel, a biblical psalm is repeated as a litany, which aptly declares, “The people´s idols are made of silver and gold. They have mouths but cannot speak. They have eyes but cannot see. They have ears but cannot hear”. I think that psalm is very modern.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —How was the process of writing for this book? It was originally suggested by José Luis Cuerda to make it into a movie.

Manuel Rivas: —It was a hybrid process. Sometimes people from the world of cinematography would broach the subject of me possibly writing a script. I was working on a novel that was basically the equivalent to the first part of Todo é silencio, the section about the characters’ childhood and youth, when the possibility of writing a script resurfaced. I was faced with this challenge and so I started working on a script for awhile. I only wrote a draft because I wasn’t convinced by it. Then I told myself that I had to finish the novel.

I remember a prologue to The Third Man where Graham Greene says, “Without a literary text, a script cannot exist”. I think that’s right. Today, I am more convinced than ever. If I hadn´t written the novel, the script would never have been developed.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Nevertheless, a considerable number of your books have been adapted to cinema. Are you happy with the results?

Manuel Rivas: —I greatly admire cinema because, especially today. it’s almost a heroic job that requires resources, complex execution, and teamwork. The job of a writer is not exactly a solitary job, because afterwards, you´re either an open body in which many people coexist or you´re not a writer. They are very different processes, different windows that sometimes look out on the same landscape. Today, if I had to choose, I’d choose the job you do simply with a pencil and a piece of paper.

In any case, it’s absurd to compare two complementary forms of expression, because we are a generation that has grown up with cinema. I find what we call poetry in many movies. When I wrote Butterfly’s tongue, for example, I never thought it would become a film. But now, when I see it, I see that world perfectly reflected. I think it’s more of an intimate relationship, rather than a rivalry, as it´s sometimes made out.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Finally, when do you feel morriña?

Manuel Rivas: —I think that a nostalgic feeling for something you have desired, or still desire, or have lost, is very common. I think that morriña and saudade is something universal. Possibly, what I feel most strongly is not so much nostalgia for the past, but nostalgia for the future. So teño morriña do porvir (I have morriña for the future).

Recommended links

- [Video] Interview with Manuel Rivas at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin, by Alfonso Fernández Cid.

- O máis estraño: A boca da literatura. Manuel Rivas’ blog.

- Manuel Rivas as a journalist. Manuel Rivas in El País.

< List of interviews

Charla con / Talk with… Manuel Rivas

Manuel Rivas nos visita hoy en nuestro Café Literario. Charlará con Alison Ribeiro (UCD, University College Dublin) sobre cine y literatura, novela y poesía o la escritura en lenguas minoritarias.

Manuel Rivas nos visita hoy en nuestro Café Literario. Charlará con Alison Ribeiro (UCD, University College Dublin) sobre cine y literatura, novela y poesía o la escritura en lenguas minoritarias.

Además, escucharemos algunos de sus poemas del libro La desaparición de la nieve (Alfaguara, 2009), que ha sido traducido al inglés por Lorna Shaughnessy en The Disappearance of Snow (Shearsman Books, 2012).

Mañana, día 27 de abril, participará junto a Kirmen Uribe en el Festival Cúirt de Literatura.

Todavía estás a tiempo de enviar tus preguntas para el encuentro digital con Manuel Rivas.

Manuel Rivas in conversation with Alison Ribeiro (UCD) on cinema and literature, novel and poetry or writing in minority languages. We will have the opportunity to listen to some of his poems from the book La desaparición de la nieve (Alfaguara, 2009), which has been translated into English by Lorna Shaughnessy in The Disappearance of Snow (Shearsman Books, 2012).

Tomorrow, 27th April, Manuel Rivas and the Basque writer Kirmen Uribe will participate at the Cúirt International Festival.

You are still in time to send your questions to our digital interview with Manuel Rivas.

Cine / Film Screening: La lengua de las mariposas / Butterfly’s tongue

Como cada miércoles a las seis, el Instituto Cervantes os ofrece una película en su acogedor Café Literario. Esta semana se proyecta La lengua de las mariposas, dentro del ciclo “Una película, un libro” .

Está basada en el relato del mismo nombre y en otro más, Un saxo en la niebla. Ambos forman parte del libro ¿Qué me quieres, amor? de Manuel Rivas.

La historia se sitúa en 1936. Don Gregorio enseñará a Moncho con dedicación y paciencia toda su sabiduría en cuanto a los conocimientos, la literatura, la naturaleza, y hasta las mujeres. Pero el trasfondo de la amenaza política subsistirá siempre, especialmente cuando don Gregorio es atacado por ser considerado un enemigo del régimen fascista. Así se irá abriendo entre estos dos amigos una brecha, traída por la fuerza del contexto que los rodea. La política y la guerra se interponen entre las personas y desembocan, indefectiblemente, en la tragedia.

Manuel Rivas (A Coruña, 1957) es escritor, poeta, ensayista y periodista considerado la voz más sobresaliente de la literatura gallega contemporánea cuya obra está escrita originariamente en lengua gallega. Es autor de varias novelas cortas destacando El lápiz del carpintero (1998), Premio de la Crítica española.

José Luis Cuerda (Albacete, 1947) es director, guionista y productor de cine español. Ha trabajado en Televisión Española realizando más de 500 reportajes y documentales. En su obra vemos una etapa, inaugurada con El bosque animado, caracterizada por un humor surrealista con profundo sabor español. Ha adaptado dos veces la obra de Manuel Rivas, La lengua de las mariposas y Todo es silencio.

A la proyección le seguirá un debate dirigido a todo tipo de público.

As every Wednesday at 6pm, Instituto Cervantes shows a new film in its cosy Café Literario. The film for this week is “The Butterfly´s Tongue”, part of the cinema series “One movie, one book”.

Based on stories from the book ¿Qué me quieres, amor? (What’s up my love?) by Manuel Rivas (A Coruña, 1957).

The story is about a young boy, Moncho who lives in a Galician town and goes to school for the first time and is taught by Don Gregorio about life and literature. At first Moncho is very scared that the teachers will hit him, as that was the standard procedure then, but after his first day at school, he is relieved that Don Gregorio doesn’t hit his pupils. Don Gregorio is unlike any other teacher, and he builds a special relationship with Moncho, and teaches him to love learning. When fascists take control of the town, they round up known Republicans, including Don Gregorio.

Manuel Rivas (A Coruña, 1957) is considered the most prominent contemporary writer, poet, essayist and journalist in Galician language. He is author of several short novels; El lápiz del carpintero is especially noteworthy. The recent film Todo es silencio by director José Luis Cuerda is based in Rivas’ novel Todo é silencio.

José Luis Cuerda (Albacete, 1947) is a Spanish film director, scriptwriter and producer. He has produced over 500 documentaries and reports for Spanish Public Broadcasting. Starting from El bosque animado, his films are notable for the surrealistic humour and a strong Spanish taste.

The screeening will be followed by an open discussion.