Blog del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín

Torre Martello

¡Felicidades Bram Stoker! / Happy birthday Bram Stoker!

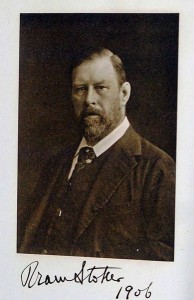

Hoy se cumplen 165 años del nacimiento del escritor irlandés Bram Stoker, este año se cumple también el centenario de su fallecimiento, en abril de 1912. Con este motivo, la ciudad de Dublín, ciudad siempre literaria, se ve colmada de actividades en honor del autor de Drácula. Y claro está, en el Instituto Cervantes no podíamos ser menos. Por ello, el día 28 de noviembre celebramos un homenaje al escritor dublinés que contará con la presencia de Luis Alberto de Cuenca y Alicia Mariño. La charla será moderada por el Dr. Jarlath Killen, profesor de Literatura Victoriana del Trinity College Dublin.

Hoy se cumplen 165 años del nacimiento del escritor irlandés Bram Stoker, este año se cumple también el centenario de su fallecimiento, en abril de 1912. Con este motivo, la ciudad de Dublín, ciudad siempre literaria, se ve colmada de actividades en honor del autor de Drácula. Y claro está, en el Instituto Cervantes no podíamos ser menos. Por ello, el día 28 de noviembre celebramos un homenaje al escritor dublinés que contará con la presencia de Luis Alberto de Cuenca y Alicia Mariño. La charla será moderada por el Dr. Jarlath Killen, profesor de Literatura Victoriana del Trinity College Dublin.

Luis Alberto de Cuenca (Madrid, 1950) escribe lo que él denomina poesía transculturalista en la cual lo trascendente se codea con lo cotidiano y la cultura popular se mezcla con la literaria. Fue director de la Biblioteca Nacional y Secretario de Cultura del gobierno español.

Alicia Mariño es licenciada en Derecho y en Filología Francesa. Ha trabajado sobre el género fantástico en distintos autores y últimamente ha orientado su labor hacia la literatura comparada, estudiando la génesis y evolución de ciertas leyendas europeas.

Instituto Cervantes Dublin is pleased to invite Luis Alberto de Cuenta and Alicia Mariño, who will pay tribute to the Dubliner writer Bram Stoker. The talk will be chaired by Dr. Jarlath Killen, Lecturer in Victorian Literature at Trinity College Dublin.

This year we are conmmemorating the 100th anniversary of Bram Stoker´s death (1847-1912). Therefore, we would like to bring the figure of this Irish mathematician and novel and short story writer closer to you. Although his work was very prolific, he has been idolized and remembered by the creation of one of the most influential horror stories in history: Dracula.

Luis Alberto de Cuenca (Madrid, 1950), one of Spain’s most famous living poets, writes what he calls ‘transculturalist’ poetry in which the transcendental rubs shoulders with the everyday, and literary and popular cultures intermingle. He uses both free verse and traditional metres and his verse is famous for its ironic elegance and its scepticism.

Alicia Mariño has a degree in Law and in French Philology. She has worked on the fantasy genre and recently she has focused on comparative literature, studying the origin and evolution of some European legends.

David Roas: Autor del mes / Author of the month

Nació en Barcelona (1965) y es profesor de Teoría de la Literatura y Literatura Comparada en la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Su trayectoria literaria se ha desarrollado en el género de la literatura fantástica, realizando diversas antologías de microrrelatos, como por ejemplo Horrores cotidianos (2007) y ensayos, como La sombra del cuervo. Edgar Allan Poe y la literatura fantástica española del siglo XIX (2011). Con su libro Tras los límites de lo real. Una definición de lo fantástico ganó el IV Premio Málaga de Ensayo, y ahora acaban de concederle el Premio Setenil, considerado uno de los premios más importantes de cuento en el panorama literario nacional.

Nació en Barcelona (1965) y es profesor de Teoría de la Literatura y Literatura Comparada en la Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. Su trayectoria literaria se ha desarrollado en el género de la literatura fantástica, realizando diversas antologías de microrrelatos, como por ejemplo Horrores cotidianos (2007) y ensayos, como La sombra del cuervo. Edgar Allan Poe y la literatura fantástica española del siglo XIX (2011). Con su libro Tras los límites de lo real. Una definición de lo fantástico ganó el IV Premio Málaga de Ensayo, y ahora acaban de concederle el Premio Setenil, considerado uno de los premios más importantes de cuento en el panorama literario nacional.

Citando sus propias palabras “Los cuentos en mi caso parten de lo cotidiano, de lo que me sucede cada día, una frase oída, una habitación de hotel “, este escritor nos sumerge en el misterio dentro de la realidad cotidiana, lo inquietante en nuestro día a día, integrando el humor con la fantasía.

Si eres lector de Hoffman o Edgar Allan Poe, seguro que este autor no te defraudará; si no conoces este género literario, te animamos a que lo descubras con David Roas. Puedes conocer más sobre él visitando el encuentro digital que realizamos el 18 de octubre.

Born in Barcelona (1965), David Roas currently works as a Professor of Literary Theory and Comparative Literature at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. His literary career has developed on the side of the fantastic literature, with several flash fiction compilations such as Horrores cotidianos (2007), and the essays like La sombra del cuervo. Edgar Allan Poe y la literatura fantástica española del siglo XIX (2011). He was awarded the IV Malaga Essay Prize with Tras los límites de lo real. Una definición de lo fantástico and he has recently received the Premio Setenil, which is considered one of the most important short story awards in Spain.

Quoting his own words: “Short stories in my case come from the daily life, my day to day experiences, from sentences I heard, from a hotel room”, this writter immerses us in the mystery underlying the reality, in the disturbing events of our everyday life, integrating humour with fantasy.

If you are a fan of Hoffman or Edgar Allan Poe this author will not disappoint you; if you are not familiar with this literaty genre, we invite you to discover it with David Roas. You can know more about him by reading his virtual interview held in October 18th at our library.

Alicia Mariño: The Fantastic is always liberating

Interview with Alicia Mariño held on 3rd March 2011 at the Dámaso Alonso Library of the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin on the occasion of her participation in the round table discussion “Many worlds” with Luis Alberto de Cuenca and Jorge Edwards.

Alicia Mariño holds a Ph.D. in French Language and Literature and a Law degree. Her doctoral thesis was on the role and significance of Fantastic literature in Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. She has since researched the Fantastic genre in the work of different authors. The results have been published as articles in various specialist journals and a book, published by Cátedra in the collection “Clásicos Universales” series, on Romance of a Mummy, by Théophile Gautier. Recently, her work has focused on comparative literature, studying the genesis and evolution of some European legends. She has also done research in the field of women’s literature.

Pilar Garrido: —Alicia, what did your interest in Fantastic literature stem from?

Alicia Mariño: —I’m not sure where it came from. I imagine I must have daydreamed a lot as a child but, more than anything else, I was a real bookworm. When I finished my degree at the Universidad Autónoma in Madrid, I put the same question to my thesis supervisor, Javier del Prado, who was the one to suggest that I do my doctoral thesis on Fantastic literature. He told me, many years after having read my thesis, that the only person from among his students who could have worked on Fantastic literature was me. The truth is that this subject always fascinated me, maybe I already had some spark, or interest, lying dormant, which I hadn’t yet discovered. I’ll never know.

Pilar Garrido: —Could you define Fantastic literature for us in a few words?

Alicia Mariño: —Hmm, that’s a difficult task. It looks as if the great theorists on the subject have finally come to an agreement. But, let’s say, if we look at a story, there’s always a strange or supernatural element which invades daily life, in such a way that the character (this all takes place within the story) can’t understand what’s happening, can’t find a rational explanation.

It’s important that the rational laws that govern both the reality of the reader and the reality of the character in the story are insufficient to explain this strange or supernatural phenomenon, which has to be narrated in a credible way. And from then on, from this doubt, from this incomprehension, the character starts to be gripped by fear, existential vertigo, anxiety, and all sorts of feelings, none of them pleasant, because of the insecurity that’s created by not knowing what’s happening.

Generally, in Fantastic literature, in its strictest sense, the story ends without an explanation. But, the most important thing is that it’s a story in which the narrative technique manages to make the implausible plausible. The perfect Fantastic stories are those which manage to move within the boundaries of what’s possible and what’s impossible, and most importantly, which don’t have a rational explanation. Sometimes, at the end of the story, but not always, there is an explanation of the event: it’s a dream, madness, cruelty.

That’s why Fantastic literature flourished as soon as rationalism was established as the prevailing philosophy. Earlier, in the Middle Ages for example, there are lots of mentions of Fantastic literature but, actually, they are only elements of the Fantastic. Because at that time when people believed in miracles and in a world in which anything was possible, Fantastic literature simply couldn’t exist since there was no clash between the rational and the irrational. In other words, strange or supernatural phenomena are not subject to an explanation, the laws of Reason.

That’s the difference between the Fantastic and fairy tales, for example. In a fairy tale, the characters are inside a story and a world in which anything is possible, in which miracles abound and which isn’t ruled by the laws of reason, so there is simply no need for any rational explanation of unusual phenomena. Therefore, there’s no distress or anxiety either resulting from a misunderstanding of something incredible that appears as plausible. We could even say that in the fairy tale, where everything is possible, nothing seems unlikely. In the Fantastic tale it’s the complete opposite.

Pilar Garrido: —Is this a genre which has a lot of followers?

Alicia Mariño: —Yes, quite a lot. It’s just that it has always been viewed as being slightly on the fringe. But I think that, in the last thirty years, there’s been quite a boom in people interested in the genre and, of course, it has some excellent authors.

Pilar Garrido: —Could you name a few?

Alicia Mariño: —I could name lots… I think I have to mention Edgar Allan Poe, and Hoffman before that, and all those who followed in their footsteps… But most of all, here in Dublin, the only person we need talk about today is Stoker, the author of one of the best novels, not just within the genre, but of all time: Dracula. It could be defined as the last great gothic novel or at least, one of the first “well-established” Fantastic novels. It’s extraordinary.

Pilar Garrido: —Do you think that in times of crisis, like we have now, people are more inclined to read Fantastic novels to escape their problems, or routine?

Alicia Mariño: —I think they are. Particularly if you take into account all this mania for vampirism, even if it is sort of teenybopper vampirism, but still, this new wave of films and novels, even for teenagers, makes me think that maybe times of crisis, and difficult times, lead us to this type of literature. Maybe because we’re all looking for more escapism, and even to exorcise fear, insecurity. In any case, the Fantastic is always liberating.

Pilar Garrido: —Do you think there are cultures or countries which have produced more of this type of literature?

Alicia Mariño: —Without a doubt. The great masters of the genre all come from the Anglo Saxon world.

Pilar Garrido: —Is there any particular reason for that?

Alicia Mariño: —I’m afraid I can’t say, because I’ve researched it, I’ve tried to study why Spain produces less Fantastic literature than other countries, but I don’t know why. Psychiatrists who have studied the topic from a psychoanalytical point of view can’t explain it either. There is much talk about the importance of landscapes, the mist, the forests, the world of legends, in moulding the Fantastic imagination, in the Celtic world, and back home in Galicia but really, the Anglo Saxons started it all. Then it spread to France and took off, and then the trend arrived in Spain. We also have great Fantastic writers, but not in the same numbers as in the Anglo Saxon world.

Pilar Garrido: —And finishing up, Alicia, you mentioned before that your surname, Mariño, has links with a legend as well. Could you explain that to us briefly?

Alicia Mariño: —Surely, in honour of Torrente Ballester who told it to me in the halls of residence, when I was studying in Salamanca, and I went up to him to ask him to sign my book. “Alicia Mariño”, he said, “wow! Don’t you know the legend about your name?”

He told me that the name “Mariño” comes from a gentleman who was strolling by the water’s edge when he fell in love with a mermaid, and went to live with her at the bottom of the sea. They had lots of children but, as the years went by, he wished he could educate his sons in the art of war. He asked the mermaid for permission to take them back on land and she granted it, on condition that from then on he would give her one person from each generation. And it is said that to this day, a blue-eyed Mariño, from each generation, loses his life at sea.

Later on, I discovered that Torrente Ballester must have been obsessed with that name because his first novel is calledJavier Mariño. I have a cousin with the same name, but the novel isn’t linked to him in any way.

Torrente Ballester also wrote a novella called El cuento de sirena, in which he recounts the legend in the first two pages and from there, he goes on to develop a 20th century legend, about a man whose surname is Mariño. The perfect crime takes place, but in the end, this Mariño is the last of a generation, he’s blue-eyed, he has an accident, and ends up in the sea. I really recommend Torrente’s novella El cuento de sirena.

Recomended linnks

- [Video] Interview with Alicia Mariño at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin by Pilar Garrido.

- [PDF] “Entre lo posible y lo imposible: El relato Fantástico”. Essay by Alicia Mariño.

- [Video] “Ubicación del género fantástico”. Lecture by Alicia Mariño at the UIMP.

- Sobre el género de terror. Alicia Mariño in El Diario Montañes.

< List of interviews

Alicia Mariño : Lo fantástico siempre es liberador

Entrevista con Alicia Mariño realizada el 3 de marzo de 2011 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en la mesa redonda “Muchos mundos” junto a Luis Alberto de Cuenca y Jorge Edwards.

Alicia Mariño es doctora en Filología Francesa y licenciada en Derecho. Realizó su tesis doctoral sobre la función y el significado de la literatura fantástica en Villiers de l’Isle-Adam. Ha trabajado desde entonces sobre el género fantástico en distintos autores. Fruto de esos trabajos han sido diferentes artículos publicados en revistas especializadas y un libro, editado por Cátedra en su colección Clásicos Universales, sobre La novela de la momia, de Théophile Gautier. Recientemente, ha orientado su labor hacia la literatura comparada, estudiando la génesis y evolución de ciertas leyendas europeas. También ha realizado estudios en el campo de la literatura femenina.

Pilar Garrido: —Alicia, ¿de dónde viene tu interés por la literatura fantástica?

Alicia Mariño: —No sabría decirte. Imagino que debí de ser una niña muy soñadora y, sobre todo, fui una niña muy lectora. Terminé mi carrera en la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, y esta misma pregunta se la hice, años más tarde, a Javier del Prado, director de mi tesis doctoral, quien me propuso el tema sobre literatura fantástica. No lo sé, Javier, que fue mi maestro, me respondió mucho tiempo después de haber defendido mi tesis doctoral, que del grupo de alumnos que trabajaba con él yo era la única que pensó que podía trabajar sobre lo fantástico. La verdad es que el tema me fascinó siempre, quizás porque había algún germen oculto, o algún interés, desconocido para mí; no lo sabré nunca.

Pilar Garrido: —¿Podrías definirnos la literatura fantástica en unas poquitas palabras?

Alicia Mariño: —Bueno, es una tarea algo complicada. Parece que, finalmente, los grandes teóricos de la materia se han puesto de acuerdo. Digamos, así muy rápidamente, que para que un relato sea considerado fantástico debe ocurrir en él que un elemento sobrenatural o extraño invada la vida cotidiana, de manera que el personaje, siempre desde el interior del relato, no puede entender lo que ocurre, no encuentra explicación racional a lo que sucede.

Es importante que las leyes racionales que rigen tanto la realidad del lector, como la realidad del personaje de la historia contada sean insuficientes para explicar ese fenómeno extraño o sobrenatural, narrado de forma verosímil. Y a partir de ahí, de esa duda, de esa incomprensión, se genera en el personaje el miedo, el vértigo existencial, la angustia, y toda una serie de sentimientos, no demasiado gratos, provocados por la inseguridad que provoca lo incomprensible.

A veces, al final del relato, aunque no siempre, se encuentra una explicación del acontecimiento, del que dan razón el sueño, la locura, la crueldad. En literatura fantástica stricto sensu, el acontecimiento queda siempre sin explicación racional. Y sobre todo, lo esencial también es que una depurada técnica narrativa realista consiga hacer verosímil lo inverosímil. Ese es el relato fantástico perfecto, el que consigue moverse ahí, en el límite entre lo posible y lo imposible, sin que exista explicación racional alguna.

Por eso, la literatura fantástica se desarrolla a partir del momento en que impera el racionalismo como filosofía ya establecida. Antes, por ejemplo en la Edad Media, se habla muchas veces de que existe literatura fantástica, y en realidad lo que hay son solo elementos fantásticos. Porque en aquel mundo en el que existe y se acepta el milagro, y en el que se cree que todo es posible, no puede haber literatura fantástica, pues no hay choque entre lo racional y lo irracional. Es decir, que los fenómenos sobrenaturales o extraños no están sometidos a la explicación, a la ley de la razón.

Esa es la diferencia, por ejemplo, entre lo fantástico y el cuento de hadas. En el cuento de hadas, los personajes están sumergidos en un relato y en un mundo en el que todo es posible, en el que impera el milagro y que no se rige, en absoluto, por leyes racionales; de ahí que la necesidad de explicación racional de un fenómeno extraño no exista y, por lo tanto, tampoco la inquietud ni la angustia que genera la incomprensión de algo inverosímil que aparece como verosímil. Incluso podríamos decir que en el cuento de hadas, en el que todo es posible, nada parece inverosímil. En el relato fantástico ocurre todo lo contrario.

Pilar Garrido: —¿Es un género con muchos seguidores?

Alicia Mariño: —Tiene bastantes, lo que pasa es que siempre ha aparecido como algo marginal. Pero yo creo que de treinta años a esta parte ha surgido mucha gente interesada por el género, y por supuesto tiene autores maestros.

Pilar Garrido: —¿Podrías citar algunos?

Alicia Mariño: —Podría citar muchísimos. Creo que si no se cita a Edgar Allan Poe, a Hoffmann anteriormente, y a todos sus seguidores… Pero sobre todo, estando aquí, en Dublín, pienso que al único que hay que citar hoy es a Stoker, el autor de una de las mejores novelas, no solamente de género, sino de la literatura universal: Drácula. Se la puede definir como la última gran novela gótica, o bien como una de las primeras novelas fantásticas, extraordinaria.

Pilar Garrido: —¿Crees que en tiempo de crisis, como hoy en día, la gente tiende a leer más este tipo de novelas fantásticas para evadirse de los problemas o de la vida diaria?

Alicia Mariño: —Yo creo que sí. Todo esto que ha surgido en torno al vampirismo, aunque ya es un vampirismo un pocolight, toda esa nueva oleada de películas y de novelas, incluso para adolescentes, me lleva a pensar que quizá los tiempos de crisis y los tiempos complicados lleven a este tipo de literatura. Quizás porque uno se evade mucho más, e incluso exorciza el miedo, la inseguridad. Lo fantástico siempre es liberador.

Pilar Garrido: —¿Crees que hay culturas o países que han producido más este tipo de literatura?

Alicia Mariño: —Sin lugar a dudas, los grandes maestros del género pertenecen al mundo anglosajón.

Pilar Garrido: —¿Y por alguna razón en especial?

Alicia Mariño: —Pues no sé decirte, porque he intentado estudiar por qué en España se da menos literatura fantástica que en otros países, pero lo ignoro. Algunos psiquiatras que han estudiado el tema desde el punto de vista psicoanalítico tampoco lo explican. Se habla mucho de la importancia del paisaje, de la bruma, de los bosques, del mundo de la leyenda para configurar ese imaginario fantástico, del mundo celta, tan de aquí y también de nuestra Galicia. Pero realmente, de los anglosajones parte todo lo fantástico en literatura. Desde ahí influyen muchísimo en Francia, y luego sí que llega la tendencia a España, donde también tenemos escritores fantásticos buenos, pero no en esa gran cantidad como en el mundo anglosajón.

Pilar Garrido: —Para terminar, Alicia, antes me comentabas que tu apellido, Mariño, tenía también relación con alguna leyenda. ¿Podrías explicárnoslo brevemente?

Alicia Mariño: —Sí, así rendimos homenaje a Torrente Ballester, que me la contó en el colegio mayor, cuando yo estudiaba en Salamanca y me acerqué a él para que me dedicara un libro. «Alicia Mariño», dijo, «¡uy! ¿Y no conoces la leyenda de tu nombre?»

Él me contó que el nombre «Mariño» pertenecía a un caballero que, paseando por la orilla del mar, se enamoró de una sirena y se fue a vivir con ella al fondo del mar. Juntos tuvieron muchos hijos, pero, pasado el tiempo, el caballero empezó a echar de menos la posibilidad de educar a sus hijos varones en las artes de la guerra. Pidió permiso a la sirena para llevárselos a tierra y educarlos en esas artes; ella se lo dio con la condición de que, de cada generación, le entregara uno. Y dicen que, desde entonces, de cada una de las generaciones, muere un Mariño de ojos azules en el mar.

Más tarde, averigüé que a Torrente Ballester debió de obsesionarle este nombre porque su primera novela se llamaJavier Mariño. Yo tengo un primo que se llama así, pero no tiene nada que ver con la novela.

Torrente Ballester también escribió un librito pequeño que se llama El cuento de sirena, donde narra, en las dos primeras páginas, esta leyenda. Y a partir de ahí, él crea una ficción ambientada en el siglo XX; es la historia de un hombre que se apellida Mariño: ocurre el crimen perfecto, pero al final, ese Mariño es el último de una generación, además tiene ojos azules y acaba, por un accidente, en el mar. La verdad es que recomiendo esa novelita de Torrente, El cuento de sirena.

Enlaces Recomendados

- [Vídeo] Entrevista realizada a Alicia Mariño en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín por Pilar Garrido.

- [PDF] “Entre lo posible y lo imposible: El relato fantástico”. Ensayo de Alicia Mariño.

- [Vídeo] “Ubicación del género fantástico”. Conferencia de Alicia Mariño en la UIMP.

- Alicia Mariño habla sobre el género de terror en el Diario Montañés.