Blog del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín

Torre Martello

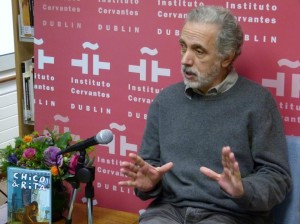

Interview with Fernando Trueba

Interview with Fernando Trueba held on the 4th of November 2012 in the Damaso Alonso Library, Instituto Cervantes Dublín, on the occasion of his participation in the roundtable “Words and Images: Cinema and Literature” with Mark O’Halloran and Javier Mariscal for the ISLA Festival 2012.

Fernando Trueba (Madrid , Spain , 1955) is a writer, editor and film director . Between 1974 and 1979 he worked as a film critic for El País and in 1980 he founded the monthly film magazine Casablanca, which he edited and managed for the first two years. In 1992 his film Belle Epoque won 9 Goya Awards , and in 1993 it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. In 1997 he published his book Dicionario del Cine (Dictionary of Cinema) and is editor of the Diccionario del Jazz Latino (Dictionary of Latin Jazz) (1998). In 2010 he directed , with designer Javier Mariscal, the animated film Chico y Rita, which received the Goya for best animated film which was selected for the Academy Awards in the category of Best Animated Film . His most recent film is El Artista y la Modelo (The Artist and the Model) (2012).

Alfonso Fernández Cid: Fernando, I have it engraved in my memory that when you received the Oscar for the film Belle Époque, you said you did not believe in God but in Billy Wilder. Do you still keep that faith?

Fernando Trueba: In Billy Wilder? Of course! For what reason would I ever lose it? There are many directors that I admire and I try to learn from, and he’s one of them. For me, directors such as Renoir, Truffaut, Bresson, Lubitsch , Preston Sturges and many others have been crucial in my development and in my life. But Billy Wilder is part of that group which has become part of me, for better or for worse.

I ‘ve always thought that Billy Wilder is the best screenwriter that ever lived. Well, II think it’s silly to claim that someone is the best director ever, for one day you may think that it is Renoir, and another day it is Lubitsch, and another it’s John Ford, and every day you’re right . Nevertheless, I challenge anyone to show me the proof that there is a better scriptwriter than Billy Wilder. Bring me the scripts with all dialogues, how they are written, structured, and I’m willing to take whatever time necessary to analyze and discuss them, because I’m sure that there is no such scriptwriter better than Billy Wilder. Never!

More than faith, it is a conviction. Faith is believing in something without seeing it. I think beyond seeing and reading, there is a kind of revelation that is felt when you see the masterpieces of Billy Wilder. You keep watching them, and the years go by and you look at them again. You know them by heart and think that you will feel nothing new watching Sunset Boulevard or The Apartment or Double Indemnity or Some Like It Hot. But you see them again and that feeling of infinite admiration for these intelligent, well-made works returns.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: How do you arrive at such a cinematic project as Chico y Rita, in which you managed to involve Bebo Valdes and [Javier] Mariscal?

Fernando Trueba: It came out of friendship. Friendship is one of the biggest incentives in my life, something that is at the source of many things I’ve done. In this case, it has been my friendship with Mariscal. It all started with Calle 54. He produced the artwork for the documentary. Then I started making records and I continued to ask him to design them for me. Because I love what he does and because we understand each other very well. I laugh a lot with him too.

One day he tells me “I’ll die without having done something I would have really loved to do: to make an animated feature film.” And I said “Surely you’ve had a thousand proposals right? Why haven’t you done one yet?” And he said “Yes, but a movie like this is not a question of hours, but of months, years, drawing by hand, bent over a table, and whenever anybody offered me anything, it was for a story I did not like. I will not lose my life, my eyes and my arms to draw a story that I do not like.”

Of course, for me animation is a totally alien world, I had never considered it before. He said to me, “For example, you will not take animation and this kind of stuff seriously. You would never give the time to write a script for an animated film.” He caught me by surprise. In essence, these conversations began the project. One day, in his study, I saw drawings of old Havana. I was overcome with enthusiasm when I saw them, “How beautiful!” I said. “This is what you need to do! This is the movie that I must make! A film in your Havana, Mariscal’s Havana. That would be spectacular!” And so it began. He said: “Yes , but it must have music.” “Man, if its a story in Havana and the Cuban people, it will be difficult for it not to have music.” “Yes, but with lots of music,” he insisted. Then I said, “Why not do a story about musicians.” “Ok, a saxophonist and a singer who fall in love.” I said that was the worst Scorcese movie ever, New York New York, I hated that movie. “Why not a pianist so, and each time he plays the piano, we put in Bebo Valdés”. And so begins a movie, slowly, like everything in life, from a sentence , an image, a conversation. And then one needs to start writing and drawing for years.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: So the journey was a long one.

Fernando Trueba: Yes, first a script is produced and many versions of it are made. Then, to convince people to believe in the project and raise the money needed to do something so expensive, it is necessary to demonstrate the style in which the film would be made. Xavi [Mariscal] then began to draw characters , backgrounds, even maps were created as a demonstration. It took several years to find the people and the money to co-produce the project. Once this is found, we had to to start with storyboards, the characters, the hundreds of animators, drawing for two years. Actually, the process took seven years. What happened was that I, in the meantime, I wrote the screenplay for one movie, produced another couple of them, and I shot in Chile for El baile de la victoria (The Victory Dance). Otherwise, I would have died. There were parts of the production during which I could do nothing but wait: we had already recorded the sound, the music, and planned the camera movement. I just had to wait for the drawings to arrive and check that all was well.

It is very strange, animation. For me, it was like facing a completely new and different world. I have to say I enjoyed it like a child. Except the wait, how long it takes, the patience that one needs. Every time a drawing arrived from Xavi, every time I received a map, it was a joy, a tremendous rush. In fact we are planning two further projects. Chico y Rita has opened many doors for us. We have co-producers in several countries interested in what we are doing next. There’s a story that is very Xavi-esque, based on the characters from Garriris, one of his first comics, and he is working on the script with a screenwriter. As for me , I’m writing another one. We want to make them together. But the first project is more for Xavi, more for his world and and affairs , and the other is a draft of a story I want to tell.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: The great jazz fans always have a love affair with the music. What is your relationship with it?

Fernando Trueba: I have been through many different stages, because I discovered jazz as a teenager through my older brother. And it got the hook in me in a big way. I remember in those early days, when I was 14 , 15, 17, and I really liked Keith Jarrett, Dave Brubeck, McCoy Tyner. After this, there was a time in my life when I distanced myself from jazz, during my college years.

It was the era of free jazz, which was too free for me. It wore me out. It was a kind of music for musicians, too experimental. There is always a moment, in all the arts, when all the isms have been exhausted and a kind of delirium tremens is arrived at: “We will write without commas”, “let’s not paint , let’s put 27 phones on the floor and call it an installation” … At that point, I remove myself. Art, at the point in which communication is severed, no longer interests me. I need to understand things for them to excite me. So I left Jazz for a few years, but I returned to it through Latin jazz. I returned because I discovered a kind of energy in Latin jazz that made me come back.

Jazz is the most adventurous music that exists. Because one must have a wide musical knowledge, outstanding technical abilities, and then one must have the courage to improvise, to create, to let yourself be carried away, to let things happen themselves. That is very beautiful. I think authors also do this. There is a moment in the writing process where the hand moves by its own accord, and one sentence leads to another. This, in music, is only experienced by a jazz musician. A jazz musician will throw himself out the window without a safety net, and sometimes he will fly.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: You worked as a film critic.

Fernando Trueba: Yes, when I was very young, between the ages of 20 and 24, when I directed my first film. But I had already dreamt of making movies. Writing reviews was an opportunity to watch movies and get paid at the same time. Once, it was proposed for me to publish these reviews but I’ve always refused. They were sincere and passionate, but I think I was very young and did not have the capacity for it then. I do enjoy reading the reviews of Truffaut though, and in my house I have books by Manny Farber, Andrew Sarris, even writers who worked as critics such as Graham Greene, Alberto Moravia or Ennio Flaiano.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: What is the importance of critics – to what extent can they have an influence?

Fernando Trueba: I think that it is a very bad period for film criticism at the moment, because criticism, in the creative sense of cinema, has practically disappeared. Nowadays there is not one critic that I follow. Hoberman and Rosenbaum, from the US, interest me, but not entirely. I think Rosenbaum, in Chicago, is one person who is doing a good job, and has more merit still, because he is doing it in the United States, a country that is very self-absorbed…the United States does not look out at the world, but only at American cinema, with the exception of a select few in New York and San Francisco. Rosenbaum is mounting a crusade, telling people about Iranian cinema, Argentine cinema, Taiwanese cinema…he is the only critic I read with even a little interest.

I think that now, criticism has become very superficial. It is newspaper criticism, made hastily and in a hurry. In addition, the articles are very small, with little detail. You can not deal with a movie in a couple of lines.

For me, criticism is an act of love. Your enthusiasm should be contagious to others – to teach how to see something, to teach how to read something, to open a window onto an artistic work. This happened to me when I was young and read Truffaut. I read it and, suddenly, the desire to see a movie arose inside me. This is wonderful – when you become enlightened, when you are given clues, when you discover things that give you joy, when you feel your life is improved. And that is what I do not feel from critics nowadays.

I think the basic condition of the critic is to have the humility to recognize that what matters is the work, that he or she is an intermediary between the work and the public. A good critic is never above what he or she writes about. Criticism needs space for it to be developed, space for ideas to be explained and contextualised.

Recommended Links :

- [Vídeo] Interview with Fernando Trueba at he Instituto Cervantes in Dublin by Alfonso Fernández Cid.

Entrevista con María Negroni

Entrevista con Maria Negroni realizada el 3 de noviembre de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en la mesa redonda “Conflictos: ficción, humor y sociedad” junto a Lorenzo Silva, Bernardo Toro y Niamh O’Connor dentro del Festival Isla de Literatura 2012.

Entrevista con Maria Negroni realizada el 3 de noviembre de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en la mesa redonda “Conflictos: ficción, humor y sociedad” junto a Lorenzo Silva, Bernardo Toro y Niamh O’Connor dentro del Festival Isla de Literatura 2012.

María Negroni (Rosario, Argentina, 1951) es poeta, ensayista y novelista. Como poeta, ha publicado, entre otros libros: Islandia (premio del PEN American Center en Nueva York al mejor libro de poesía en traducción del año 2001), El viaje de la noche, Arte y Fuga, La Boca del Infierno y Cantar la nada. También ha publicado varios libros de ensayos y dos novelas. Ha traducido, entre otros, a Emily Dickinson, Louise Labé, Valentine Penrose, Georges Bataille, H.D., Charles Simic y Bernard Noël, y la antología de mujeres poetas norteamericanas La pasión del exilio (2007). Su libro Galería Fantástica recibió el Premio Internacional de Ensayo de Siglo XXI (México).

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —María, en tu literatura se repite en varias ocasiones la palabra “isla” que además es la misma palabra que da nombre a nuestro festival literario. ¿Qué te sugiere esta palabra?

María Negroni: —La palabra “isla” es casi como un sinónimo de la poesía. Porque la isla en general, al menos imaginariamente, sugiere un territorio rodeado por agua, un territorio a-isla-do. Sugiere un territorio virgen, lleno de posibilidades, vacío. Una isla es también como un cuerpo. Podríamos decir que las personas somos islas rodeadas de muerte, en realidad. En ese espacio aislado, es posible crear mundos. La isla es como una miniatura de un gran continente, como lo es también el poema, que es pequeño. Es como un universo pequeño, pero abierto a infinitas posibilidades.

Uno de mis primeros libros se llama “Islandia”, que es el territorio de la isla, del mimo modo que uno dice Disneylandia, el país de Disney. Islandia es el país de la isla. Lo escribí hace mucho tiempo y fue, digamos, un viaje y también una especie de tributo a Borges, que amaba la literatura islandesa. Pero claro, en mi caso, hice una especie de mezcla porque uní ese tributo a las hadas islandesas con el viaje de una mujer contemporánea a otra isla, que en este caso era Manhattan.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Relacionado con ello, has mencionado el principio de lo femenino en la poesía y la literatura fantástica. ¿Cuál es su verdadera dimensión e importancia?

María Negroni: —Esto daría para una charla muy larga, pero podríamos sintetizarlo diciendo que en la literatura fantástica como en la literatura gótica (de la cual lo fantástico es una deriva) y en la poesía, hay un principio de insubordinación frente al pensamiento racional, luminoso, solar, de la razón y el orden. A mí me parece que en esos géneros, igual que en la poesía, hay como una especie de surgimiento desde abajo, desde un principio que viene como a erosionar o a corroer: el principio de la luz. Y eso podríamos sintetizarlo diciendo que es el deseo. El deseo, como principio insubordinado, digamos, es, para mí, femenino. Si te fijas en las grandes obras de la literatura fantástica o gótica, siempre lo que está abajo, lo que está en las criptas, en los subsuelos, siempre tiene que ver con el principio de lo femenino, con la noche, con el cuerpo, con el deseo, básicamente. Con la poesía sucede lo mismo. Por eso la poesía es tan importante, porque ahí es donde la palabra cobra, por asi decirlo, su mayor carga antiautoritaria.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —¿Lo gótico sigue todavía presente en la actualidad de la literatura latinoamericana?

María Negroni: —Sí. No de la misma forma que en el siglo XVIII en inglés, pero sí tiene una presencia, dado que el deseo y lo nocturno, y lo que se escapa al mundo de la razón no va a dejar de existir jamás. Eso se va como mudando y va tomando nuevos rostros y nuevas expresiones. El fantástico latinoamericano del siglo XX es una deriva directa del gótico inglés. Digo “directa”. En mi libro “La galería fantástica” trato de probar esta premisa. El gótico está presente en el cine negro norteamericano de mitad del siglo XX. No olvides que los directores norteamericanos que hicieron cine negro son los expresionistas alemanes que venían huyendo del nazismo y que se reinventaron en Hollywood. El gótico está muy presente, con otros rostros y otros nombres. Pero sigue vigente.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Cuando escribes ¿lo haces desde la experiencia o desde lo desconocido?

María Negroni: —Siempre he pensado que la poesía es una especie de epistemología del no saber. Es decir, que uno para escribir tiene que ir a lo que no sabe. Porque como dice George Steiner, la belleza tiene que ver con la ruptura, la ruptura de lo sabido, de lo convencional. Si uno va a repetir algo que sabe, no se produce ningún efecto estético. El efecto estético se produce con las preguntas sin sus respuestas. Por eso la escritura viene del lugar de lo que se desconoce y, en todo caso, el trabajo del poeta o la poeta es ahondar en ese desconocimiento, porque siempre se puede ir más abajo. Siempre se puede, como diría Beckett, fracasar mejor.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —¿Cuál crees que es el paraíso de un poeta?, ¿cuál sería tu paraíso como poeta?

María Negroni: —Lo primero que me viene a la cabeza es decirte que el paraíso sería una biblioteca. Porque en realidad los libros, en mi opinión, son como conversaciones con otros libros escritos por otros autores. Son como conversaciones con otras almas. Por eso una biblioteca sería el lugar paradisíaco por excelencia. En lo personal, creo que la respuesta sería la misma. Escribir y leer es una misma cosa. Casi te diría que la carrera literaria del lector, es la carrera literaria más difícil. Saber leer. Entonces creo que sí. No sé si está mal decir esto, pero con los libros soy absolutamente feliz.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Llevas ya unos cuantos años residiendo en Estados Unidos, concretamente en Nueva York. ¿Hay alguna marca de esta ciudad en alguna de tus obras?

María Negroni: —Yo creo que me ha influido mucho. Llegué a Nueva York en el año 85. Tengo dos etapas ahí. Con una etapa en Buenos Aires en el medio. Y sí, Nueva York me dio vuelta a la cabeza. Es una ciudad que me pasé diez años descubriendo, explorando. Estaba absolutamente fascinada por la ciudad durante la primera década, mientras era estudiante. Era otra Nueva York. También yo era otra persona. Hoy por hoy, la ciudad me resulta un poco menos interesante que lo que me resultaba en los años ochenta. Es una ciudad que se ha, como dicen en inglés, “gentrified”,”gentrificado”, no sé como se dice en español. Es una ciudad mas pulcra, más limpia, más rica. Me gustaba más antes, cuando era más sucia, más abismal.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —También influyó quizás que antes conservaba el encanto de resultar una ciudad inabarcable.

María Negroni: —Puede ser. Pero también se ha transformado. Hoy es una ciudad un poco más homogénea, muy rica. Es como un shopping mall, un gran almacén. Incluso los barrios, donde los artistas se van moviendo, ahora se han ido a Brooklyn. Ahora Brooklyn es el nuevo Manhattan. Entonces me resulta menos interesante, pero de todas maneras es una ciudad que me ha dado muchísimo y volvería a hacer la misma experiencia. Y además, por todo el tema que se está hablando en este festival: el desfasaje, el salirse del lugar, el correrse de sitio, ha sido fundamental para mí porque me ha permitido tomar una actitud como desmarcada frente a mi propio medio, que es el medio argentino. Me ha dado mucha libertad. En Argentina, creo que soy una escritora medio inclasificable, que me muevo siempre como corriéndome de los géneros. Nueva York me legitimó eso.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Te dio una cierta libertad.

María Negroni: —Total. No sé si la hubiera tenido de haberme quedado en Buenos Aires.

Enlaces Recomendados

- [Vídeo] Entrevista realizada a María Negroni en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín por Alfonso Fernández Cid.

Entrevista con Rafael Gumucio

Rafael Gumucio: Vivir con culpa es horrible y vivir sin culpa es peor

Entrevista con Rafael Gumucio realizada el 3 de noviembre de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en la mesa redonda “Escritores sin escrúpulos: Intimidad, violencia y humor en la literatura” junto a Ita Daly, Christopher Domínguez Michael y Catherine Dunne dentro del Festival Isla de Literatura 2012.

Rafael Gumucio (Santiago, Chile, 1970) ha trabajado como periodista en numerosos diarios nacionales chilenos, españoles y en el New York Times. En 1995 publicó el libro de relatos Invierno en la Torre y la novela Memorias prematuras. Posteriormente salieron a la luz Comedia nupcial, Los platos rotos yPáginas coloniales. Su última obra es La Deuda (2009). Actualmente es Director del Instituto de Estudios Humorísticos de la Universidad Diego Portales y co-conductor del programa Desde Zero en Radio Zero.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Rafael, eres escritor y humorista, pero escribes cosas muy serias Hay novelas como La deuda, por ejemplo, en la que haces una denuncia de un Chile actual en el que pasan muchas cosas.

Rafael Gumucio: —Yo generalmente escribo cosas serias, no intento ser cómico. En la vida real, parece que soy bastante más cómico porque soy torpe y me resultan las cosas distintas a como yo quiero hacerlas. Sí creo que lo que escribo tiene cierto humor, en el sentido de que tiene una visión un poco más amplia de la realidad. No hay ninguna idealización, los personajes están mostrados en su pequeñez, su ridiculez y en su belleza también. Está todo junto. Para mí la palabra humor significa eso. Significa ser capaz de ver la realidad en todos sus amplios matices No considero que el humorista sea alguien que haga chistes o que sea alguien divertido.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Además en La deuda hablas de la culpa. Hace poco Javier Marías hablaba de que se ha perdido el sentimiento de culpa. Antes todo hacía que nos sintiéramos culpables y ahora todo vale. ¿Por qué crees que hemos pasado de un extremo a otro?

Rafael Gumucio: —Yo creo que es un cambio de sociedad. Es un cambio que tiene que ver con una cierta economía. Chile es un ejemplo paradigmático de ello porque Chile vivió una revolución neoliberal de una gran importancia. Hicimos reformas neoliberales antes y más profundas que otros. Esto en un país católico, culposo, con un pasado político cristiano y socialista y comunista lleno de culpabilidad, crea en las personas evidentemente una especie de choque imposible de absorber entre lo que aprendieron de pequeños, lo que aprendieron de su familia, y lo que la sociedad les está pidiendo.

La novela se llama La deuda porque uno de los principios básicos de la economía neoliberal es que uno tiene que deber. La deuda no es un problema, es una cualidad. El dinero no es el que tú tienes sino el que adeudas. Y esa deuda nunca se paga… Hasta que nos damos cuenta de que al final sí se paga, como ha pasado en España y en todas partes del mundo. Pero la idea que se nos vendió durante veinte o treinta años es «Mira, tú no puedes vivir con el dinero que tienes debajo del colchón, no puedes vivir con tus ahorros, tienes que endeudarte y luego la deuda te hace parte de la sociedad». La deuda se transforma en una especie de ciudadanía, de identidad. El banco pide que tú tengas deuda, hasta que ya no pudiste pagar. Pero al principio el banco le dijo a la gente «Endéudense. Paguen esto a veinte, a treinta años». Y claro, en la vieja cultura, la cultura del ahorro, de solo pagar lo que tengo cuando lo tengo, es la vieja cultura de la culpa, que también tiene que ver con eso, con qué responsabilidad tengo yo en lo que pasa a los demás. Esa cultura fue combatida y produjo un choque.

La transición chilena y lo que pasó en Chile me resultaba muy llamativo porque creo que eso se trasladó a la vida privada, íntima mía y de todos mis amigos, y quise transcribirlo. Yo no soy un sociólogo, no pretendo hacer novela sociológica, pero me interesaba justamente ese nuevo equilibrio entre una cultura que reivindica la culpa y el arrepentimiento, el escrúpulo, y otra cultura que piensa que el arrepentimiento y el escrúpulo es un bloqueo, es una forma de no progreso, de quedarse estancado en la nada, y cómo esas dos culturas chocan en la vida privada, íntima, de las personas, y construyen nuevos personajes monstruosos.

Yo mismo he tenido que romper con la culpa en la que fui educado, yo mismo he tenido que ser parte de esta sociedad liberal, y lo he hecho con alegría. La novela me hizo descubrir el valor de la culpa, que es un valor paradojal porque lo que yo digo es que la culpa es muy empequeñecedora, es muy triste, es muy bloqueante, pero es mejor que la no culpa. Es decir, la otra promesa, la vida sin culpa, es un desierto sin remisión. La verdad es que no prometo ningún paraíso. Vivir con culpa es horrible y vivir sin culpa es peor.

Carmen Sanjulián: Cuando se produce el golpe de estado en Chile, tú solamente tenías tres años y te vas con tu familia al exilio. Sin embargo, tu abuelo funda el partido democristiano en Chile, tu padre también se implica ayudando a muchos otros. Eso, aunque eras un niño, evidentemente te marcó, y de ahí quizás surge Platos rotos.

Rafael Gumucio: —Sí, la verdad es que la historia política de Chile era algo completamente íntimo en mi caso, del día a día, absolutamente cotidiano. Yo pasé los primeros años de mi vida en París, exiliado, y aquello era como vivir doblemente en Chile.

Vivíamos mentalmente en Chile y en la historia de Chile. Mi abuelo, mi bisabuelo y casi toda mi familia estuvo implicada en la historia de un país que es muy pequeño y muy familiar, y sucede un poco como pasa con Dublín: a veces, sociedades muy pequeñas y muy provinciales, sin demasiada importancia, se ven implicadas en la historia. En el caso de Dublín, en la historia literaria de una manera totalmente desproporcionada. El símbolo Chile, lo que Chile significa para el mundo, lo que significó para la historia, no tiene nada que ver con su tamaño, la cantidad de habitantes o la productividad del país. Somos un país de América Latina pequeño, sin embargo, hemos producido una cantidad de símbolos mundiales importantes.

Como yo tenía acceso a esta fuente, para mí era interesante contar nuestra historia. Paradojalmente, este libro nació cuando yo vivía en Madrid. Cuando uno vive fuera empieza a obsesionarse con el país propio. De hecho, decidí volver a Chile porque no quería ser tan chileno. Estaba transformándome en un ser folclórico.

Carmen Sanjulián: ¿Cómo fue tu vuelta a Chile? ¿Te sentiste exiliado al llegar?

Rafael Gumucio: —Fue una experiencia que todavía no puedo calibrar. Yo viví hasta los catorce años en París y llegué a Chile en plena dictadura, en plena crisis económica, en un momento de miseria y con mucha represión. Apenas llegamos, apareció una lista de gente que no podía estar en Chile, así que viví clandestino seis meses, aunque a los catorce años no había hecho aún nada. Todo me invitaba a arrancar y huir. Sin embargo, el hecho de sentirme «importante», tan importante como para estar clandestino, resultó un alivio en un joven con problemas de autoestima y que había sufrido toda la dislexia y toda la represión de la cultura francesa. Así que extrañamente, llegué a un lugar que era un purgatorio, si no un infierno, y me resultó un paraiso, me sentí cómodo inmediatamente.

Por otro lado, ser escritor en Chile en esa época era algo absolutamente imposible y sin ningún futuro, y a los catorce o quince años, las cosas imposibles son una gran ayuda porque te protegen de la realidad. Todo lo que me salía mal en la vida pasaba a un segundo plano porque yo estaba embarcado en un proyecto absolutamente solitario y que requería todo mi tiempo, espacio y mente.

Carmen Sanjulián: —¿Te han dado muchas veces gato por liebre?

Rafael Gumucio: —Sí, pero yo también lo he hecho a veces.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Gato por liebre es uno de los programas de humor que tenías, junto con Plan Z. ¿Cómo te embarcaste en esa historia?

Rafael Gumucio: —También por azar, porque como ser escritor en Chile era imposible, porque no había editoriales ni lectores, tuve que embarcarme en el periodismo y hacer un poco de todo. Yo veía mucha televisión y escribía una crítica de televisión en una revista. Alguna gente la leyó y le dio la idea de que yo podría hacer televisión.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Contra la belleza, un ensayo en el que criticas de alguna manera la sociedad en la que vivimos, que premia la belleza. ¿Qué hay de verdad en eso?

Rafael Gumucio: —Es contradictorio, porque los parámetros estéticos son muy importantes para mí. Juzgo a las personas por su belleza o por su fealdad y soy bastante superficial. Me hice una autocrítica. Nació una colección en la editorial Tumbona, una editorial mexicana, que era contra distintas cosas, y me dijeron contra qué quería escribir, y dije «bueno, contra la belleza». No tenía ninguna idea, pero al investigar, me di cuenta de que la idea de la belleza visible, o de la belleza perceptible, ha sido uno los problemas del arte.

El arte ha luchado en contra de la belleza, porque la belleza tiene una implicación política esencial que es lo que me interesaba denunciar. Creo que pasa un poco como con La deuda. La belleza es el símbolo más atractivo de la injusticia. La injusticia social o genética encuentra en la belleza un ejemplo vivo. Podríamos vivir en una sociedad totalmente igualitaria, podríamos todos ganar lo mismo, pero siempre habrá unos que serán más bellos que otros y, fatalmente, los bellos se casarán entre sí y tendrán hijos más bellos aún, y luego se creará una sociedad en la que los bellos gobiernen a los feos.

Cuando las sociedades son más desiguales, la belleza crece en ellas, y cuando las sociedades son más igualitarias, la belleza es perseguida. Por supuesto, es un juego de suma cero, porque ninguna de las dos puede ganar totalmente la batalla. Dios sabe que si yo viviera en una sociedad igualitaria en que la belleza fuera perseguida, no podría soportarlo. Soy más capitalista que socialista, pero entiendo perfectamente que hay un problema ahí y que la belleza no es inocente. Se nos dice: «si a usted le gusta la belleza y odia la fealdad, tiene que soportar las injusticias sociales porque son del mismo orden: hay gente más bella que otra, hay gente más fuerte que otra y hay gente más rica que otra. Así son las cosas y no van a cambiar». Ese es el discurso que hay detrás de la propaganda de la belleza que me resulta intragable.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Escribes Memorias prematuras con veintinueve años. ¿Cómo se te ocurre?

Rafael Gumucio: —De hecho fue una condena, porque después de eso ya no tengo nada más que decir… No, fue un reto también suicida, porque un amigo mío había leído una entrevista en la que yo contaba un poco mi infancia y adolescencia y me dijo: «Tienes que escribir sobre eso».

Yo estaba en un momento de alto desprestigio literario. Había escrito un libro que había sido destruido por la crítica, y esto me pareció una salida, no sé porqué. Me pareció que tenía una doble ventaja. Si el libro salía mal, mi muerte era permanente. Y si el libro salía bien, era un gesto de audacia. Y lo hice cuando todos mis amigos se burlaban, pensaban que era un gesto de arrogancia. Porque además, el libro lo escribí a los 29 años, pero la trama del libro termina cuando yo tengo 26, ni siquiera escribí hasta los 29. Y claro, lo pensé como una novela. Todos los datos son reales, todos los personajes son reales, pero la estructura en que está pensado es como una especie de novela en la que intento mostrar un aprendizaje y el choque de un joven con la idea que él mismo se ha hecho de si mismo y que su padre o su sociedad le ha hecho, que es la idea de ser un genio. Y cómo este joven tiene que descubrir que es normal. Lo que siempre es una decepción muy grande.

Enlaces recomendados

- [Vídeo] Entrevista realizada a Rafael Gumucio en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín por Carmen Sanjulián.

- Artículos de Rafael Gumucio en El País.

- Rafael Gumucio en Twitter.

Interview with María Negroni

Interview with Maria Negroni held on the 3rd of November 2012 in the Dámaso Alonso Library, Instituto Cervantes Dublin, on the occasion of her participation in the ISLA Festival round table discussion “Conflicts: Fiction, Humour and Society” along with Lorenzo Silva, Bernardo Toro and Niamh O’Connor.

María Negroni (Rosario, Argentina, 1951) is a poet, essayist and novelist. As a poet, she has published, among other books, Islandia (winner of the award for the best book of poetry in translation, 2001, from the PEN American Center in New York), El Viaje de la Noche (The Journey of the Night), Arte y Fuga (Art and Fugue), La Boca del Infierno (Hell’s Mouth) and Cantar Nada (Sing Nothing). She has also published two novels and several books of essays. She has translated works by Emily Dickinson, Louise Labé, Valentine Penrose, Georges Bataille, H.D., Charles Simic and Bernard Noël among others, as well as La Pasión del Exilio (The Passion of Exile), an anthology of female American poets (2007). Her book Galeria Fantástica (Fantastic Gallery) received the International Essay Award of the 21st century (Mexico).

Alfonso Fernández Cid: María, in your literature the word “island” is repeated on several occasions, the same word that gives its name to this literary festival. What does this word suggest to you?

María Negroni: The word “island” is almost a synonym for poetry. Because in general an island, at least in an imaginary sense, suggests a land surrounded by water, an isolated territory. It suggests a virgin terrain, empty, full of possibilities. An island is also like a human being. We could say that people in reality are islands surrounded by death. In this isolated space, it is possible to create new worlds. The island is like a miniature version of a great continent, just as a poem is. It is like a universe, tiny in size, but open to endless possibilities.

One of my first books is called Islandia (Iceland), which is the territory of the island, in the same way that one says Disneyland, Disney-country. Islandia is the country of the island. I wrote it a long time ago and it was, I would say, a journey but also a kind of tribute to Jorge Luis Borges, who loved Icelandic literature. Of course in my case I created a kind of cocktail because I united Icelandic fairy mythology with a story of a contemporary woman’s journey to another island, in this case Manhattan.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: In relation to this, you have mentioned the principle of the feminine in poetry and fantasy literature. What in your opinion is its true dimension and importance?

María Negroni: This would make for a lengthy discussion, but we could distill it by saying that in fantasy literature and Gothic literature (of which the fantastic is a derivation), and in poetry, there is a principle of insubordination against clear, rational, illuminated thought, reason and order. It seems to me that in these genres, as well as in poetry, there as a kind of emergence from below that comes so as to erode or destroy. And that could be compounded by saying that this emergence is desire. Desire as a disruptive concept is, for me, feminine. If you look you in great works of Gothic or Fantasy literature, always that which is below, in the crypts, in basements, this always has to do with the principle of the feminine, with the night, with the body – desire, basically. The same thing happens with poetry. This is why poetry is so important, because it is here where words realise, so to speak, their greatest anti-authoritarian potential.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: Is the Gothic still present nowadays Latin American literature?

Maria Negroni: Yes. Not in the same way as in 18th-century English literature, but it does have a presence, given that desire, all things nocturnal, that which escapes the world of reason, will never cease to exist. It is always shifting, always taking new faces and new expressions. Latin American fantasy literature of the 20th century is a direct derivation of the English gothic novel. Again I say – a direct derivation. In my book The fantastic Gallery I try to test this premise. The Gothic is present in American film noir of the first half of the 20th century. Do not forget that the American directors who made film noir were German Expressionists who arrived fleeing Nazism and who reinvented Hollywood. The Gothic is very present, with other faces and other names. But it remains in force.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: When you write do you do so from experience or from the unknown?

María Negroni: I have always thought that poetry is a kind of epistemology of unknowing. That is, for one to write, one has to venture into the unknown. Because as George Steiner says, beauty is connected to the idea of rupture, the rupture of the known, the conventional. If one was to repeat something they know already, no aesthetic effect is produced. This aesthetic effect arises from questions that have no answers. For this reason, writing comes from the place that remains unknown and, in any event, the work of the poet is delve into that unknown, because you can always explore further. One can always, as Beckett says, fail better.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: What do you think is the paradise, for a poet? What would be your paradise as a poet?

María Negroni: The first thing that comes into my head is to tell you that paradise would be a library. Because books, in my opinion, are in reality conversations with other books written by other authors. They are like conversations with other souls. So a library would be paradise par excellence. From a personal perspective, I think that the answer would be the same. To read and to write are the same thing. I would almost say that the job of the reader is the most difficult literary occupation – to learn to read. Then I think so, yes. I don’t know if it is wrong to say this, but with books I am absolutely happy.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: You have been, for some years now, residing in the United States, specifically in New York. Has the city left a mark upon any of your works?

María Negroni: I think it has influenced me a lot. I came to New York in 1985. I have had two stages there, with a period in Buenos Aires in between. And yes, New York left me spinning. It is a city that I spent ten years discovering, exploring. I was absolutely fascinated by the city during the first decade, while I was a student. It was a very different New York; I was someone else also. These days the city is a little less interesting that how it appeared to me in the 1980s. It is a city that is has become, as they say in English, “gentrified”. It is a neater city, cleaner, richer. I prefered it before, when I was dirtier, more dingy

Alfonso Fernández Cid: Perhaps you were influenced by the fact that before, it maintained a charm of being an unfathomable city.

María Negroni: This could be true. But now it has also become transformed. Today the city is a little more homogeneous, and very rich. It is like a shopping mall, a huge store. Even the neighbourhoods – where artists hang out, now they have all gone to Brooklyn. Brooklyn is now the new Manhattan. So i find it less interesting, but in any case it is a city that has given me a lot, and I would do it all again if I had the chance. And furthermore, for all the themes that are being discussed in this festival: the space in-between, dislocation, departure from a place, [New York] has been fundamental for me because it has allowed me to have a detached attitude towards my own environment, the Argentinean. It has given me a lot of freedom. In Argentina, I think that I am a sort of unclassifiable writer, that I move constantly, fleeing genres. New York legitimized me in this sense.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: It gave you a certain freedom.

Maria Negroni: Completely. I don’t know if I would have had that freedom if I remained in Buenos Aires.

Recommended Links

- [Vídeo] Interview with María Negroni at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublín by Alfonso Fernández Cid.

Entrevista con Elia Barceló

Elia Barceló: La literatura es más grande que la vida

Entrevista con Elia Barceló realizada el 2 de noviembre de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en la mesa redonda “Literatura fantástica y poesía: de Cortázar a Beckett, pasando por Borges”, junto a Harry Clifton y Bernardo Toro, dentro del Festival Isla de literatura 2012.

Elia Barceló (Alicante, España, 1957) ha publicado novelas policiacas, históricas, de ciencia ficción y de género fantástico para adultos, así como novelas para jóvenes y ensayos. En 2007 recibió el Premio Gabriel 2007, galardón reservado para las más importantes personalidades del género fantástico en España. Su obra ha sido traducida al francés, italiano, alemán, catalán, inglés, griego, húngaro, holandés, danés, noruego, sueco, croata, portugués, vasco, checo, ruso y esperanto. Sus novelas traducidas al inglés hasta la fecha son Corazón de tango (2007) (Heart of Tango, 2010) y El secreto del orfebre (2003) (The Goldsmith’s Secret, 2011). En 2013 se publicaron los dos primeros volúmenes de su trilogía Anima mundi.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Elia, los entendidos dicen que eres maestra de las palabras. Escribiste El almacén de las palabras terribles y yo creo que dejaste las palabras terribles en ese almacén y tú te quedaste con las palabras hermosas.

Elia Barceló: —Esa es una de mis ideas. Para mí, seguramente porque vivo en el extranjero, la lengua, mi lengua, es una cosa fundamental. Para mí las palabras son un auténtico tesoro. No es hablar por hablar, es algo que mimo y aprecio.

Carmen Sanjulián: —En tus novelas siempre intentas romper muchos estereotipos: sobre los roles sexuales, sobre la identidad… Serías una buena política.

Elia Barceló: —Jamás, nunca. Yo quizás podría ser una buena amiga de un político, por ejemplo, para poderle decir las barbaridades que están haciendo. Pero yo misma no sería capaz. Yo soy partidaria de pequeños grupos que funcionen autónomamente. Si yo pensara que el anarquismo funciona en realidad, yo sería absolutamente anarquista.

Carmen Sanjulián: —La ciencia ficción, que cada vez tiene más seguidores, todavía se considera como la hermana pobre de la literatura. ¿A qué es debido?

Elia Barceló: —A mil cosas. Supongo que muchísima gente habla mal de la ciencia ficción sin haber leído nunca ciencia ficción. Han visto un par de películas en la tele. Con un poco de mala suerte, han visto lo peor que la ciencia ficción tiene que ofrecer. Y entonces piensan que son memeces para descerebrados y cosas así.

He escrito 19 libros y solo tres de ellos son de ciencia ficción, pero creo que la ciencia ficción es de los pocos géneros literarios que ofrece temas nuevos. Todos los demás géneros tratan básicamente sobre lo mismo que trataba la literatura hace dos mil años. La ciencia ficción es la única que abre nuevos caminos. Y seguramente, para muchos lectores eso es algo que asusta. Porque hace falta trabajar más. Cuando entras en una novela de ciencia ficción, no la entiendes de golpe. Tienes que poner mucho de tu parte.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Hay una simbiosis entre el mundo de la ciencia y los escritores de ciencia ficción.

Elia Barceló: —Sí, a mí me llamaba mucho la atención cuando yo era jovencita y leíamos cosas que ya trataba la ficción, por ejemplo temas como la clonación de niños. Este tipo de problemas que ahora ya son reales. En aquella época, daba la sensación de que eran locuras y tonterías que se inventaban unos cuantos. Y yo pienso que es importante que nos vayamos planteando cierto tipo de cosas que van a venir. La literatura hace entre otras cosas que uno vea el mundo de otra manera, con otros ojos. Y por eso la ciencia ficción es un gran desafío. Hay muchos géneros que también lo son.

Carmen Sanjulián: —¿Qué son, si no ciencia ficción, los recuerdos que tenemos?

Elia Barceló: —Los seres humanos somos narradores, eso es básico. Todo ser humano necesita narrar. Y uno se narra a sí mismo su propia historia. Hay cosas en las que uno sabe que se está mintiendo a sí mismo, porque siente vergüenza, porque no le parece presentable. Otras veces, cuando ya has contado algo cuatro o cinco veces, ya no eres consciente de que estás mintiendo. Tienes clarísimo que fue así. Por eso escribí una novela que se llama Disfraces terribles, que trata justamente de eso, de alguien que trata de hacer una biografía de un gran autor argentino y tiene la idea de que preguntándole a la gente que lo conoció y leyendo sus textos podrá recrearlo. Pero se va dando cuenta de que el recuerdo es una creación.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Si los habitantes de Umbría vieran el panorama que tenemos hoy, no solamente en Europa sino especialmente en España, ¿qué dirían?, ¿cómo actuarían?

Elia Barceló: —Los pobres habitantes de Umbría están habituados a todo, porque Umbría es una región autonómica española creada por cuatro escritores hace unos diez años en la que todo es posible. La gracia de Umbría es que allí todo es normal. Hay carreteras normales y aeropuertos y restaurantes, pero todos sus habitantes saben que allí pasan cosas raras y de eso no se habla. Se sabe, pero no se habla. Se mirarían y dirían que así son las cosas.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Hasta ahora has situado todas tus novelas en Umbría. ¿Estás escribiendo alguna otra situada en ese mundo de ficción?

Elia Barceló: —No. En este momento no. Éramos cuatro autores y el único que continuó escribiendo, además de mí misma, fue César Mallorquí. Los otros lo dejaron, por eso todavía no tengo claro si de verdad vale la pena que continuemos montando ese mundo. Ahora, la novela que estoy escribiendo pasa en este planeta, pero en todas partes. Tengo veinticinco localizaciones o algo así.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Como la ciencia ficción es un género que no es bien conocido, algunos lo han aprovechado a veces para robar ideas. ¿A ti te ha pasado alguna vez con alguno de tus libros?

Elia Barceló: —Yo me figuro que es confluencia. Nunca pienso que me roban ideas. Creo que la literatura, en la base, es como una especie de cajón del tesoro de los piratas donde, cuando tú abres la tapa, hay tantas cosas bonitas y tienes la sensación de que no son de nadie en concreto, son de todos. Y empiezas a ponerte collares, pendientes, cosas y no te das cuenta de que a lo mejor pertenecía a otra persona. Yo no creo que nos roben ideas, no hace falta.

Carmen Sanjulián: —A ti te gusta visitar los lugares en los que se sitúan tus novelas y experimentar. ¡Alguna vez incluso has perseguido a alguien para ver lo que se siente!

Elia Barceló: —Sí… Generalmente todo va muy bien, no pasa nada. Pero en el primer momento, cuando alguien te dice «¿por qué me mira usted tanto?» Entonces le dices: «mire, lo encuentro a usted muy interesante, porque estoy escribiendo una novela y tengo un personaje como usted». Entonces ya se ponen muy simpáticos y muy agradables.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Una de tus últimas experiencias ha sido el tango. Sitúas Corazón de tango en ese mundo fascinante de los años 20. Tu visita ahora a Buenos Aires, ¿ejerció en ti la misma fascinación?

Elia Barceló: —Una de las gracias de la literatura en general es que es más grande que la vida. Cuando uno describe algo literariamente en una historia, le toca más, le llega más. Ves unas imágenes que son mucho más potentes que las que luego tiene cuando estás allí. De hecho, yo empecé a escribir Corazón de tango básicamente cuando dejé de bailar. El tango es un baile donde es el hombre quien manda, quien te lleva, quien decide, quien lo hace todo. Y mi marido dijo «mira chica, yo ya empiezo a cansarme mucho de esto del tango». Seguramente porque entendía las letras y me me decía «es que es insoportable estar cuatro o cinco horas oyendo cómo se queja alguien porque lo han abandonado». Como ya no bailábamos, empecé a escribir.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Lo que está clarísimo es que eres una mujer tremendamente curiosa, que experimenta y escarba en muchos campos.

Elia Barceló: —Sí. Una cosa muy típica de mí es que cada novela que hago es otra cosa. Tanto mis editores como mi agente me dicen «podrías coger una línea y que tus lectores ya supieran lo que hay que esperar». He hecho novela histórica, criminal, fantástica, de terror, realista, de todo. Lo que estoy haciendo ahora no tiene todavía una etiqueta concreta. Es una especie de thriller. Es una trilogía, es grandísimo, van a ser mil trescientas páginas o así. Es un thriller actual, que sucede en este mundo, donde hay unos cuantos elementos fantásticos que cada vez son más fuertes y más potentes, y un final inesperado o sorprendente. Al menos eso espero. Y espero que os guste y que lo leáis, se llama Anima Mundi.

Enlaces Recomendados

- [Vídeo] Entrevista realizada a Elia Barceló en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín por Carmen Sanjulián.

- Elia Barceló en Conocer al autor.com.

- Entrevista a Elia Barceló en el diario ABC.es sobre la publicación de Anima mundi.

< Listado de Entrevistas

Audiolibro de la semana | Audiobook of the Week: Esta noche moriré

Con un inicio tan enigmático como “me suicidé hace dieciséis años”, Fernando Marías escribe una inquietante novela que te atrapará desde el primer momento. ¿Quieres escucharla en forma de audiolibro? Coge tu carnet de la biblioteca y haz click aquí.

Con un inicio tan enigmático como “me suicidé hace dieciséis años”, Fernando Marías escribe una inquietante novela que te atrapará desde el primer momento. ¿Quieres escucharla en forma de audiolibro? Coge tu carnet de la biblioteca y haz click aquí.

Delmar, un policía obsesionado en detener a un importante delincuente, se encuentra, 16 años más tarde de que consiga meterlo entre rejas, con que éste ha urdido un estratégico y macabro plan para vengarse. Aunque Delmar no es capaz, siquiera, de imaginar lo que le espera cuando recibe una larguísima carta. La estratagema del delincuente consiste en conseguir que acabe suicidándose, mostrándole hasta qué punto ha sido capaz de manipular su vida desde hace ya unos cuantos años.

This novel has an enigmatic beginning : “I committed suicide sixteen years ago”. Fernando Marías writes a disturbing novel that will hook you from the very first moment. Do you want to listen to it as an audiobook? Take your library card and make click here.

Delmar, a police man obsessed with arresting an important criminal, finds outs that he has created a strategic and macabre plan for revenge 16 years after putting him in jail. Delmar cannot imagine though what is coming when he receives a very long letter. The stratagem of the delinquent consists of making him commit suicide, showing him how he has been manipulating his life for quite a long time.

Elia Barceló, nuestra autora del mes en el Festival ISLA / Elia Barceló, our author of the month

Elia Barceló (Alicante, 1957) estará con nosotros en el Festival ISLA de Literatura los días 2 y 3 de noviembre. Por eso, y para que conozcas un poco mejor su obra, la hemos seleccionado como autora del mes de noviembre en nuestra biblioteca.

Elia Barceló (Alicante, 1957) estará con nosotros en el Festival ISLA de Literatura los días 2 y 3 de noviembre. Por eso, y para que conozcas un poco mejor su obra, la hemos seleccionado como autora del mes de noviembre en nuestra biblioteca.

Elia Barceló reside en Austria desde 1981 donde es profesora de literatura hispánica.

Su campo de investigación es la literatura fantástica, de ciencia ficción y de terror, así como la narrativa argentina y cubana del siglo XX, la novela negra y la literatura juvenil en España. Se la considera una de las escritoras más importantes, en lengua castellana, del género de la ciencia-ficción, junto con la argentina Angélica Gorodischer y la cubana Daína Chaviano. Las tres forman la llamada “trinidad femenina de la ciencia-ficción en Hispanoamérica”.

Ha publicado novelas, ensayo y unos cuarenta relatos. Parte de su obra ha sido traducida al francés, italiano, alemán, catalán, inglés, griego, húngaro, holandés, danés, noruego, sueco y esperanto.

Elia Barceló (Alicante, 1957) is our author of the month in November. She will be with us in the ISLA Literary Festival the 2nd and the 3rd of November, so you have a good chance to know better her literary works.

She lives in Austria since 1981 where she teaches Spanish Literature. Her field of activity is Fantastic Literature, Science Fiction and Horror. She´s also interested in the Argentinian and Cuban narrative of the XX century, crime fiction and books for children and young adults.

She has published novels, essays and over forty short-stories. Part of her work has been translated into French, Italian, German, Catalan, English, Greek, Hungarian, Dutch, Danish, Norgewian and Esperanto.

Audiolibro de la semana | Audiobook of the Week: En primera línea

Emoción para el audiolibro de esta semana: En primera línea escrito por el periodista Baltasar Magro. Para descargarlo solo necesitas tu carnet de biblioteca y hacer click aquí.

solo necesitas tu carnet de biblioteca y hacer click aquí.

Beirut, 1982. Helena y Luis, dos corresponsales de Televisión Española, y Álex, novato periodista de la agencia EFE, viven de cerca el sitio a los últimos reductos palestinos y la tensión de la guerra del Líbano. Envueltos en la angustiosa atmósfera de la guerra, y en medio de la desolación, surge entre ellos una buena amistad que perdurará con el paso de los años.

La relación entre Luis, Helena y Álex, encuadrada en el mundo real de los medios de comunicación, constituye el eje esencial de esta novela.

El autor de esta trepidante novela perfila un relato intenso para describirnos los secretos de la profesión periodística con una fascinante trama que nos sumerge en los entresijos de la televisión. Baltasar Magro ha trabajado durante más de 30 años en diferentes cadenas como guionista de programas culturales y como director de diferentes espacios informativos, entre los que destaca el mítico Informe Semanal.

An exciting story for the audiobook of the week: En primera línea, written by journalist Baltasar Magro. To download it, just get your library card and press here!

Beirut, 1982. Helena and Luis work as correspondents for the Spanish National Broadcast and Alex is a new journalist working for EFE Press Agency. The three of them live first- hand the siege to the last Palestinian strongholds and the strains due to the war in Lebanon. Involved in the distressing atmosphere of war, a good friendship arises among them in the middle of desolation, lasting through the years.

The relationship between Luis, Helena and Alex, framed in the world of communication media, is the subject matter of this novel. Baltasar Magro outlines an intense story to describe the secrets of Journalism with a fascinating plot that immerses us in the secrets of television.

The author of this exciting novel has been working for over 30 years in different television broadcasters as screenwriter for cultural programmes and director of several news programmes, among which highlights the mythical “Informe Semanal”.

Interview with Ángel Guinda

Ángel Guinda: Being a Poet is Not a Profession, It’s a Possession

Interview with Ángel Guinda held on the 22nd October 2012 at the Dámaso Alonso Library of the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin in association with his participation in the literary reading “Useful poetry: commented reading”.

Ángel Guinda (Zaragoza, 1948) is best known for his poetry. In the early eighties, he published his collected poetry in Vida ávida, where the rawness of his words and a self-destructive nature stood out. In 1987, Ángel moved to Madrid, which gave way to a more existentialist style of poetry with titles likeConocimiento del medio, La llegada del mal tiempo and Biografía de la muerte. With the new Century, Guinda’s attempt to better communicate and connect with people, led to a more open and unified style of poetry. With Claro interior and Poemas para los demás, his work began to appeal to a wider audience. In 2010, he received the Premio de las Letras Aragonesas prize. Since then, he has published three poetry collections: Espectral (2011) Caja de lava (2012) andRigor Vitae (2013).

Carmen Sanjulián: —Ángel, you’ve been writing for many years. Do you remember your first poem?

Ángel Guinda: —I think my first poem was a ballad, when I was 12, to celebrate (I’m almost embarrassed to mention it) my stepsister’s First Communion.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Embarrased? Why?

Ángel Guinda: —Well, because of the way life has changed… They say, “If you’ve lived, you’ve seen it all”. When I was young, I was an altar boy, I had to study Greek and Latin. I went to mass and was Christian, Catholic, Apostolic and Roman, until I reached 30, which is when I lost my faith.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Things have changed a lot. You not only write poems, but also theorise about poetry and the role of the poet in society, which lead yout to publish poetic manifestos such as Poesía y subversión, Poesía útil, Poesía violenta, o El mundo del poeta. El poeta en el mundo. Why do you have this need to write, to reflect?

Ángel Guinda: —That´s a really interesting question. I began to theorise about poetry when I already had my own poetic style. I already knew where I wanted to go and roughly what voice I wanted to project. Then I started to ask myself the big questions, “What is the word?” I thought the word was about being alive, so I answered myself, “The word is a living thing”. I was self-evident and I explained this to my students. “What is a poet?” I argued, “Being a poet is not a profession, its a possession”. “What is a poem?” “What is poetry? I mean, I started to ask myself the fundamental questions in order to reaffirm my style and my own voice.

Carmen Sanjulián: —You wrote one of your manifestos at the Casa del Poeta in Trasmoz. You where the first guest and you began with a hunger strike. Has anything changed since then?

Ángel Guinda: —Very little, unfortunately. I remember that among the literary claims there was one in Euskadi that vindicated the poetry and the great Basque poets who hardly wrote anything in Basque, but in Spanish, like Blas de Otero or Gabriel Celaya – poets who did so much for the advent of freedom in Spain.

When I attended a tribute to Celaya, in the village where he was born, his widow, Amparo Gastón, was there, and I witnessed tomatoes being thrown at them, at the widows of Blas de Otero, Sabina de la Cruz… I crumbled. It seemed a terrible injustice to me. Apparently now there is more respect for the poetry of Gabriel Celaya and Blas de Otero, especially after the truce was called.

I also pushed, for example, for the opening of a Poet’s House in each of the autonomous communities of Spain, there´s still only one in Trasmoz, as the only centre for literary translation is in Tarazona. On top of this, I called for 0% VAT on literature. Although almost nothing has been achieved since then, it had some impact at the time and I felt great support from my literary colleagues and readers in general.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Paradox is a distinguishing element in your poetry, but it´s also an element that distinguishes you in life.

Ángel Guinda:—Yes, because as Cernuda said “It is not love that dies, but we ourselves”… I am eternally in love with life and I believe in the immortality of love but then I admit that I married four times. This is an example of paradox in my life, but there are many more…

Carmen Sanjulián: — Poets have been described as being cursed, is there such a thing as a poet who is blessed?

Ángel Guinda: —I think I´m blessed. Even though Ángel Crespo coined the term “Ángel Guinda, cursed poet” in a study about.my poetry. As a poet, I´m blessed.

Carmen Sanjulián: —How come?

Ángel Guinda: —Because I think I’m a good person. I want to be, and I think I am, a good guy. If we interpret being cursed as voluntarily choosing to be on the fringes of society, with little power and influence, then I am

Carmen Sanjulián: —You defend the idea of poetry as something useful. In what way has poetry helped you?

Ángel Guinda: —It has helped me in a lot of ways. It has helped me as a means of expression. For me, expressing yourself is part of being alive. When you have more and better ways of expressing yourself, you feel more alive.

I use poetry as a means of expression, of communication, of understanding and a way of looking at the world. Not only in terms of aesthetics but also in the way I face the world with a resilient attitude. Life is marvellous, that´s true, but life is very hard for everyone, it´s really challenging and feeling positive can be the contradiction to death.

Carmen Sanjulián: —This is one of the topics that you regularly visit.

Ángel Guinda: —Sure – life, death, the passing of time that erodes everything…

Carmen Sanjulián: —So you´re saying that poetry is useful. A few days ago I read that they´re thinking of making economics a compulsory subject in schools. Do you think they´ll ever make poetry compulsory?

Ángel Guinda: No, I don´t, unfortunately. It has nothing to do with looking out for our own interests, but unfortunately, no. I have given language and literature classes in secondary school and have tried to make my syllabus live up to the generation of 1936, which has helped me develop effective teaching tools to capture the students attention and try to motivate them. These include using song lyrics, including rap (students really like this), using the class as a translation workshop, using audiovisual aids…

Poetry is really interesting because it´s a cultural medium, like art or music, but it requires attention, dedication and a special method of teaching so that students, and especially adolescents, become interested in it.

Carmen Sanjulián: — You´ve had a lot of success with your students though. David Francisco, a student of yours, directed the film «La diferencia», based on your life. He mentioned in an interview that students regularly requested you, as you had a way of opening up their eyes to the world.

Ángel Guinda: —It´s funny you mention that because three years before my retirement, I thought that nobody knew I was a poet.But then they began to check my books out of the library and soon they were discovered by the media.

Carmen Sanjulián: —In Entrevista a mí mismo, a documentary also made by David Francisco, we see Ángel Guinda bare all. Was it difficult for you?

Ángel Guinda: —No it was quite easy actually, because I had a poem called “Entrevista a mí mismo” and I had the idea to develop different characters, so I dressed up as a journalist, and afterwards a poet, to become myself. It was very interesting.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Do you distance yourself from labels or do you have any hidden weaknesses?

Ángel Guinda: — Poetically speaking, I´ve always stood out. When I was younger and used childish language, people said that I always did my own thing. The critics said it…Manuel Rico also mentioned it when he reviewed Caja de lava.

I’ve always been a poet who did my own thing and haven´t given into trends. Think of my very dear and admired colleague´s so-called “poesía de la experiencia” or “poesía de la diferencia”, or “decadent aestheticism“…

But it’s true that for many years I admired two great poets of my generation – Pere Gimferrer and Leopoldo María Panero, until about ten years ago.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Has anything changes since you received the “Las Letras Aragonesas” award in 2010?

Ángel Guinda: —Yes, there has certainly been some changes. After leaving Aragon 23 years earlier, I was surprised to receive such an honour from my people in 2010. At first I was surprised, but then I felt honoured. I promised not to let them down, resolving to remain honest and demanding more from myself, in order to get the most out of this constant learning experience that is poetry. The apprenticeship where I learned my craft was with the great Catalan poet Salvador Espriu.

Carmen Sanjulián: —You wrote a poem about Lavapiés, the neighbourhood where you live, amongst other things. When you look for an image of Ángel Guinda, it´s almost impossible to find a picture of you without a cigarette in your hand. Have you ever written a poem about your constant companion?

Ángel Guinda: —Twenty years ago I wrote a poem I know by heart, unfortunately, and it goes like this:

I have smoked life

as time has smoked me.

Look at this larynx, this trachea,

these bronchi and lungs

gunned down by nicotine.

I have smoked the underground fumes

of the subway, of its platforms;

Madrid air, dirty,

like a betrayal of the most beautiful light;

…

And speaking of smoke…my latest project, Rigor vitae, which I´ve been working on compulsively for the last six months, features numerous crosses, a lot of smoke and countless shadows. Of course, smoke symbolises many things. Smoke prevents us from seeing the reality around us.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Is your latest project closer to Espectral or Caja de lava?

Ángel Guinda: —Espectral. People surprised me a lot by saying it was the best book I had written. The truth is that it was written in a state of euphoria, in a trance for nine months. It´s a book that amasses all a poet’s obsessions – with authenticity and with all his inner demons. The ghost of the mother who dies bleeding in childbirth, the ghost of infertility and not being able to have children, etc… But I’ve come to realise that the reality around me is more haunting than the phantom of a work of poetry. So much to say that my writing opposes reality and this is not what it´s about.

Rigor vitae is closer to Espectral than the figurative poetry of Caja de lava .

Carmen Sanjulián: —I went to the launch of Caja de lava. So many comments were made about the title!

Ángel Guinda: —It has a very interesting story, at least for me, personally. When the book was in the works, it was called Caja débil (Fragile Box). But I’m a hypochondriac. Although I have the self-destructive instinct to smoke, I also have a fear of death. So I began to wonder if “fragile box” was really a metaphor for the rib cage, because this was so bad. So I tried to revitalise myself a little bit, inject more fire, more energy into my work, and so the title became Caja de lava (Box of Lava).

Recommended links

- [Vídeo] Interview with Ángel Guinda at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin by Carmen Sanjulián.

- Ángel Guinda Official Website.

- Interview with Ángel Guinda in Poesía para todos.

< List of interviews

Entrevista con Ángel Guinda

Ángel Guinda: Ser poeta no es una profesión, es una posesión

Entrevista con Ángel Guinda realizada el 22 de octubre de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en el recital literario “Poesia útil: lectura comentada”.

Ángel Guinda (Zaragoza, 1948) es conocido sobre todo por su obra poética. A principios de los ochenta, recogió su poesía asumida hasta ese momento enVida ávida, donde destaca la crudeza de sus textos y lo autodestructivo de su propuesta. En 1987 comienza su etapa madrileña, que dio paso a una poesía más existencialista con títulos como Conocimiento del medio, La llegada del mal tiempo y Biografía de la muerte. Con el nuevo siglo, su afán de comunicar y transmitir le ha llevado a una poesía muy abierta y solidaria, llegando con Claro interior a un público más amplio que se identifica con sus Poemas para los demás. En 2010 recibió el Premio de las Letras Aragonesas. Desde entonces ha publicado los poemarios Espectral (2011) Caja de lava (2012) y Rigor vitae(2013).

Carmen Sanjulián: —Ángel, llevas muchísimos años escribiendo. ¿Recuerdas tu primer poema?

Ángel Guinda: —Creo que mi primer poema fue un romance, cuando yo tenía doce años, con motivo, casi me da pudor decirlo, de la primera comunión de mi hermanastra.

Carmen Sanjulián: —¿Pudor? ¿Por qué hablas de pudor?

Ángel Guinda: —Bueno, porque la vida evoluciona tanto… Dicen que «el que vive, a todo llega». Yo de niño era monaguillo, había estudiado griego, latín, iba a misa, y era cristiano, católico, apostólico y romano, hasta que a los treinta y tantos perdí la fe.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Han cambiado mucho las cosas. No solamente escribes poemas, sino que además teorizas sobre la poesía y sobre el papel del poeta en el mundo. Y de ahí manifiestos poéticos como Poesía y subversión,Poesía útil, Poesía violenta, o El mundo del poeta. El poeta en el mundo. ¿Por qué tienes esa necesidad de escribir, de reflexionar?

Ángel Guinda: —Es muy interesante la pregunta. Porque yo empecé a teorizar acerca de la poesía cuando ya tenía muy asentado, digamos, el estilo poético propio. Es decir, cuando ya sabía por dónde quería ir y qué voz, aproximadamente, quería tener. Entonces comencé a hacerme las grandes preguntas: ¿Qué es la palabra? Y me respondía: La palabra es un ser vivo. Y me lo autodemostraba. Y se lo explicaba a mis alumnos en el Instituto. Y ¿qué es ser poeta? Y decía: pues ser poeta no es una profesión. Ser poeta es una posesión. ¿Y qué es el poema? ¿Y qué es la poesía? Es decir, empecé a hacerme yo grandes, entre comillas, preguntas fundamentales para reafirmarme en mi estilo y reafirmarme en mi propia voz.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Uno de esos manifiestos lo escribiste en la Casa del Poeta en Trasmoz. Tú fuiste el primer invitado a esa casa, que inauguraste además con una huelga de hambre. ¿Ha cambiado algo desde entonces?

Ángel Guinda: —La verdad es que muy poco, por no decir nada, lamentablemente. Recuerdo que, entre las reivindicaciones literarias había una que defendía revalorizar en Euskadi la poesía y a los grandes poetas vascos que no escribieron mayoritariamente en euskera sino en español, como Blas de Otero o Gabriel Celaya. Poetas que tanto hicieron por la llegada de las libertades a España.

Cuando he asistido, en el pueblo de Gabriel Celaya, estando allí su viuda, Amparo Gastón, a un homenaje a Celaya y he contemplado que les tiraban tomates, o a la viuda de Blas de Otero, Sabina de la Cruz… Yo me desmoronaba. Me parecía de una injusticia atroz. Parece ser que ahora hay más respeto, sobre todo con la llegada de la tregua, por la poesía de Gabriel Celaya y de Blas de Otero.

Reivindicaba también, por ejemplo, la inauguración de una Casa del Poeta en cada una de las comunidades del territorio español, pero la única sigue siendo la de Trasmoz, del mismo modo que la única casa del traductor está en Tarazona. También reivindicaba el IVA 0 para los libros de literatura. En realidad, no se ha conseguido apenas nada, pero sí que en su momento tuvo cierta repercusión y me sentí bastante apoyado por compañeros de la literatura y por los lectores en general.

Carmen Sanjulián: —La paradoja es un elemento singularizador en tu poesía, pero también es un elemento que te singulariza en la vida.

Ángel Guinda: —Sí, porque cuando pienso, como decía Cernuda que «no es el amor quien muere, somos nosotros mismos»… Yo soy un eterno y constante enamorado de la vida, y creo en la inmortalidad del amor, pero luego me doy cuenta de que me he casado cuatro veces. Aquí hay un ejemplo de paradoja en mi existencia personal, pero se dan muchísimos más.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Se habla de poetas malditos. ¿Hay poetas benditos?

Ángel Guinda: —Yo. Yo soy un poeta bendito. Pese a que Ángel Crespo en los años ochenta acuñase el término «Ángel Guinda, poeta maldito», en un estudio sobre mi poesía. Yo soy un poeta bendito.

Carmen Sanjulián: —¿Por qué?

Ángel Guinda: —Porque creo que soy buena persona. Creo y quiero ser buena gente. Ahora, si entendemos como malditismo el estar voluntariamente situado en el margen y al margen del poder o de lo hegemónico, pues en ese sentido sí lo soy.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Tú defiendes la idea de la poesía como algo útil. ¿En qué te ha ayudado a ti la poesía?

Ángel Guinda: —Me ha ayudado en todo. Me ha ayudado como medio de expresión. Para mí, expresarse es vivir, y cuanto más y mejor consigues expresarte, te sientes más vivo en ti y entre y para los demás.

A mí la poesía me ha servido como medio de expresión, como medio de comunicación, como medio de conocimiento y como actitud ante el mundo, no solo en lo estético, sino también en el sentido de hacer frente a la existencia con una actitud resistente. La vida es maravillosa, ¿verdad? Pero la vida es muy dura para todos, es muy difícil, y paradójicamente, como decíamos antes, el poeta es contradictorio y la vida, siendo todo lo maravillosa que puede ser, tiene la contradicción de la muerte.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Es uno de los temas que tú utilizas asiduamente.

Ángel Guinda: —Claro, la vida, la muerte, el paso del tiempo que todo lo erosiona…

Carmen Sanjulián: —Dices que la poesía es útil. Hace unos días leía que estaban pensando poner la asignatura de economía en las escuelas como obligatoria. ¿Será algún día obligatoria la asignatura de poesía?

Ángel Guinda: No, lamentablemente. Y tampoco se trata de arrimar el ascua a nuestra sardina. Pero lamentablemente, no. Yo he dado clases de lengua y literatura en educación secundaria, y he intentado hacerme mis propios programas procurando llegar por lo menos hasta la Generación del 36, y procurando ayudarme de una didáctica de la mayor eficacia posible para captar la atención y para conseguir motivar a los alumnos. Utilizando textos de canciones, incluso de rap, que a los alumnos les gusta mucho, utilizando el aula como taller de traducción, utilizando los audiovisuales…

La poesía es muy interesante porque es un medio de cultura. Es cultura como lo es la pintura, como lo es la música, pero requiere de una atención, una dedicación y una didáctica muy especiales para que el alumnado, sobre todo los adolescentes, se interese por ella.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Y sin embargo, sí que tuviste éxito con tus alumnos. David Francisco, un alumno tuyo, rodóLa diferencia, una película de trazos de tu vida. Él comentaba en una entrevista que siempre había un grupo de alumnos que te buscaban para que tú les abrieses de alguna manera los ojos al mundo.

Ángel Guinda: —Sí, además es curioso porque hasta que faltaron tres años para mi jubilación, yo procuraba que nadie supiese que era poeta. Pero empezaron a llegar libros a la biblioteca y se fueron enterando por los medios.

Carmen Sanjulián: —En Entrevista a mí mismo, que es un documental que también realizó David Francisco, vemos a Ángel Guinda al desnudo. ¿Fue difícil hacer esa entrevista?

Ángel Guinda: —No, fue muy fácil, porque el poema existía, un poema que se llama «Entrevista a mí mismo». Y bueno, tuve la feliz idea de elaborar diferentes personajes, me vestía para hacer de periodista y luego para hacer de mí mismo, de poeta. Y entonces, aprendiendo de memoria las preguntas y respuestas, se pudo hacer bien. Fue muy interesante.

Carmen Sanjulián: —¿Estás desmarcado de las marcas, o tienes por ahí alguna debilidad inconfesable?

Ángel Guinda: —Bueno, poéticamente he estado siempre bastante desmarcado. Es decir, si fuera un joven y utilizase un lenguaje juvenil, diría que siempre he ido a mi bola. La crítica lo dice. Manuel Rico también lo dijo cuando reseñó Caja de lava.

He sido un poeta que he ido a mi bola, o sea, que no me he alineado con las tendencias dominantes. Pensemos en la poesía de la experiencia de mis muy queridos y admirados compañeros, o la poesía de la diferencia, o el esteticismo decadente…

Sí que es cierto que yo admiro desde hace muchos años a dos grandes poetas de mi generación que son Pere Gimferrer y Leopoldo María Panero hasta hace diez años.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Premio de las Letras Aragonesas 2010. ¿Ha cambiado algo desde entonces?

Ángel Guinda: —Sí, ha cambiado. Es una sorpresa, porque llevando en ese momento, en 2010, veintitrés años fuera de Aragón, recibí la sorpresa de sentirme querido por mis paisanos. Primero me sorprendió y luego me recompensó infinitamente. Y en tercer lugar, me compromete a no defraudarles intentando seguir siendo honesto, exigiéndome al máximo para mejorar cada vez más dentro de este aprendizaje constante que es la poesía. Aprendizaje que me enseñó en su propia casa uno de mis primeros maestros, que fue el gran poeta catalán Salvador Espriu.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Has hecho un poema a Lavapiés, el barrio donde vives, y a muchas otras cosas. Pero cuando buscas una imagen de Ángel Guinda, es casi imposible encontrar una imagen sin un cigarrillo en la mano. ¿Has hecho algún poema a tu inseparable compañero?

Ángel Guinda: —Hace veinte años escribí un poema que me sé de memoria, lamentablemente, y que comienza así:”

Me he fumado la vida

como el tiempo se me ha fumado a mí.

Mirad esta laringe, esta tráquea,

estos bronquios y pulmones

ametrallados por la nicotina.

He fumado los gases subterráneos

del Metro, en sus andenes;

el aire de Madrid, sucio,

como una traición a la luz más hermosa;

…

Y el humo… En mi último proyecto, Rigor vitae, en el que llevo trabajando compulsivamente en los últimos seis meses, aparecen muchas cruces, aparece mucho humo y aparecen muchas sombras. Claro, el humo es símbolo de muchas cosas. El humo no nos permite ver la realidad que nos rodea.

Carmen Sanjulián: —¿Ese último proyecto estaría más cerca de Espectral o de Caja de lava?

Ángel Guinda: —De Espectral. Espectral fue un libro con el que la gente me sorprendió, diciendo que era lo mejor que había escrito. La verdad es que fue escrito en una situación de rapto, de trance durante nueve meses, que recoge todas las obsesiones del poeta, con toda autenticidad y todos los fantasmas de una vida interior. El fantasma de la madre muerta en el parto, desangrándose, el fantasma de la esterilidad por no poder tener hijos, etc. Pero luego yo me he dado cuenta de que para mí es más fantasmal la realidad que me rodea que lo espectral de una obra poética. Hasta tal punto de afirmar que escribo contra la realidad, no sobre ella.

Rigor vitae está más cerca de Espectral que de la poesía figurativa de Caja de lava.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Vi la presentación de Caja de Lava. ¡Cuántas cosas se dijeron a propósito del título!