Blog del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín

Torre Martello

Audiolibro / Audiobook: La debutante

La protagonista de esta novela recuerda los pasos que, de la nada y a través del crimen, la llevaron a triunfar en una sociedad, en la que ser “de baja ralea y escasos posibles” no es un impedimento para hacer fortuna. A partir del reconocimiento de esta”‘verdad” indiscutible, nace, tras años y años de existencia gris y rutinaria, una heroína poco convencional.

Su autora, Lola Beccaria, es doctora en Filología Hispánica por la Universidad Complutense. Desde el año 1987 trabaja en la Real Academia Española, donde ha realizado diversos trabajos como lexicógrafa y lingüista.

Además de diversos relatos, artículos de prensa y de investigación, ha publicado seis novelas: La debutante (1996), La luna en Jorge (finalista del Premio Nadal 2001), Una mujer desnuda (Anagrama, 2004), Mariposas en la nieve (Anagrama, 2006), El arte de perder (Planeta. Premio Azorín 2009) yZero (Planeta, 2011).

La debutante es nuestro audiolibro de la semana. Lo tienes a un clic de distancia. ¡Descárgalo ya!

The protagonist of this novel recalls the steps she took to succeed in a society where being “of low birth” is not an impediment to making a fortune. Upon recognition of this “truth” without question, our unconventional heroine was born, after years of gray and routine.

The author, Lola Beccaria, a PhD in Hispanic Philology from the Complutense University, works since 1987 in the Royal Spanish Academy of Language, where she has held various jobs as a lexicographer and linguist.

In addition to various reports, press articles and research, she has published six novels: La debutante (1996), La luna en Jorge (Nadal Prize finalist 2001), Una mujer desnuda (Anagrama, 2004), Mariposas en la nieve (Anagrama , 2006), El arte de perder (Planeta. Azorin Award 2009) and Zero (Planeta, 2011).

La debutante is our audiobook of the week. It’s a click away from you. Download it now!

Kirmen Uribe en el Festival Cúirt de Literatura / Kirmen Uribe at the Cúirt International Festival

Kirmen Uribe participa esta tarde junto a Manuel Rivas en el Festival de Literatura de Cúirt.

Kirmen Uribe participa esta tarde junto a Manuel Rivas en el Festival de Literatura de Cúirt.

Kirmen Uribe, escritor, poeta y ensayista vasco, escribe sus obras en lengua vasca. La publicación en el año 2001 del libro de poemas “Bitartean heldu eskutik” (Mientras tanto dame la mano), supuso, según el crítico literario Jon Kortazar, una “revolución” dentro del ámbito de la literatura vasca. En 2009 recibió el Premio Nacional de Narrativa por su novela “Bilbao-New York-Bilbao”.

Kirmen Uribe and Manuel Rivas will participate this evening in the Cúirt International Festival.

Kirmen Uribe, Basque writer, poet and essayist writes his work in the Basque language. According to the literary critic Jon Kortazar, his work “Bitartean heldu eskutik” (Hold my hand in the meantime), published in 2001 amounted to a revolution in the Basque language. He was awarded the Spanish Literature Prize for his novel “Bilbao-New York-Bilbao” in 2009.

Interview with Manuel Rivas

Manuel Rivas: A Word is a Loaf of Bread Made Up of Light and Shadow

Interview with Manuel Rivas on the 26th April 2012 at the Dámaso Alonso Library of the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin, in association with his participation in the discussion “Literary encounter with Manuel Rivas”.

Manuel Rivas (A Coruña, 1957) is a writer, poet, essayist and journalist. Some of his works have been adapted to film. One of his best known works isButterfly’s Tongue, based on three stories from the book ¿Qué me quieres amor? (1996), for which he received the Premio Nacional for Spanish fiction. O Lápis do Carpinteiro has been published in nine countries and is, to date, the most translated book in the history of the Galician language. En salvaje compañía (In the Wilderness) and Los libros arden mal (Books Burn Badly), which won the Premio Nacional de la Crítica for Galician fiction, have also been translated into English. Todo é silencio (2010) (All is silence, Radom House, 2013) was a finalist for The Hammett Award for crime-writing. His latest novel,Las voces bajas, was published in Spain in 2012.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Manuel, in Butterfly’s tongue, the main character, Moncho, is a boy who is a bit scared on his first day of school. Do you remember this phase of your life?

Manuel Rivas: —My first school was a kind of creche and I was very young, I´d only just started to talk. I went with my sister who was a little older because my mother had to work. I remember I carried a plastic bag and, as there were so many of us, there was no place to sit. With the best intentions, one of the two sisters who brought us, sat me down on the kind of suitcase that children have for storage, and so I spent a year there sitting quietly on a suitcase. It was a kind of premonition of emigrant lineage. I sat there with my case, and one day, I opened the case and realised it was empty. There was nothing in it.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —As we´re discussing memories, do you remember when you first started writing?

Manuel Rivas: —That’s a process. I don’t think there’s a day you wake up saying, “I’m a writer”. I started to write very early, but they were just notes I made in a notebook. I called them poems. There’s even an anecdote about my godfather, who had a small typewriter and encouraged me to write. As it was a typewriter for receipts, it had a small carriage, so I thought it would be better to write poetry. That was the idea I had about poetry. But anyway, we’re talking about playing with words.

If I really had to choose a moment, I think it would have to do with listening. For me, that’s the first tool for a writer, as well as a journalist. So, if I had to say where the writer in me was born, it would be in a place of listening, which was a staircase in my maternal grandparents’ house – a country house in Galicia. It was a staircase where you could hide after you were sent to bed. You’d stay hidden in a sort of ascending wooden tunnel, while the stories the adults told would come filtering up the steps.

Álvaro Cunqueiro spoke of a group of sailors who understood the language of the sea. In a time when there were no such advanced forecasting tools, they could anticipate storms through signs and murmurs of the sea. They were called “the listeners” (os escoitas) and were rumoured to have one ear larger than the other. I think a writer also needs to have something like that – an ear, a conch shell larger than the other.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —You have always felt a passion for journalism. Do you think there is still that strong bond between journalism and literature?

Manuel Rivas: —Yes. There are a large number of people who have shared the status of being both a writer and a journalist. I think it´s good for a writer to have feelers, that grounding that a journalist needs to have – the principle of an active reality. Also, it’s necessary for a journalist to have a flare for style when it comes to writing.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —As a writer, do you have any routine, any rituals when it comes to writing?

Manuel Rivas: —No, I’m not very methodical. I think it’s a struggle when you write. Our body is a battlefield on which alternative energy struggles, the energy that always enables you to write and to overcome the moments of dejection. This erotic energy, this force of desire sometimes has to fight with what we call Thanatos.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —In your work, there are several literary genres. Do you feel any preference for one in particular?

Manuel Rivas: —I would represent it with the image of concentric circles. The topic of genres gives way to a theoretical reflection, a necessity to classify. But in the end, what exists is the mouth of literature. Either it exists or it doesn’t. You can find it in different forms, but it’s true there can be very poetic tales where the poetry vibrates. There can be texts presented as literary, but we don’t really perceive that vibration, that liveliness. We don’t see the mouth of literature opening. Sometimes, the mouth of literature opens in life, in a bus, in a bar, in a conversation or in the odd discussion.

I think the core of literature is poetic, that’s the first circle. The expression, “The secret zone of the human being”, is a need to express the enigmatic reverse of the mirror. That’s why I think that a way of detecting what defines literature is that it simultaneously reveals, works with light, and creates a new enigma, a new secret. It also has a strong resemblance to a camera obscura. In this case, the the light that enters through the small hole and is transformed, in conflict with the darkness and the shadows, represents the words. A word is a loaf of bread made up of light and shadow.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —What language do you feel more comfortable writing in?

Manuel Rivas: —I started writing literature in Galician and still do. I still write a big part of my work in Galician. It’s a first love and feels good, but it’s also true that the relationship between language is not a relationship of struggle or exclusion. When that is suggested, it has nothing to do with words or with language, it acts as another kind of manipulation. Actually, what languages want is to embrace each other. So I feel I would like to write in many languages. But in the end, the truth is that you have to master your own language, and that’s true whether you’re writing in Galician, in Spanish or in Inuit.

Marcel Proust used to say that the ideal way to write is with the feeling that you’re writing in an unknown or foreign language. In the end, the purpose of writing is to bring something into existence that wasn’t there before, like a new species. Even if it’s something that resembles a nettle growing out of a handful of dirt.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Your last book Todo é silencio is structured in two parts – Silencio amigo (Friendly Silence) and Silencio mudo (Mute Silence). I think Rosalía de Castro’s enthusiasts are delighted with that wink. Why did you choose these two titles for your novel?

Manuel Rivas: —Yes, Silencio mudo is an expression that appears in a poem by Rosalía called Follas novas. “Todo é silencio mudo soidá dolor…” There are different types of silence. We could go further and include undertones, but fundamentally, there’s a friendly silence that is a fertile silence, the silence, for example, that corresponds to each musical note, a note of silence. It’s a silence that helps you, a creative silence. On the other hand, it´s the root of literary creation.

The counterpoint is the silence that doesn’t help creativity, that isn´t fertile, but an imposed or acute silence. I remember a phrase that was written by an inquisitor when he ordered the cutting off of an Indian´s ears in the Andes. It’s a phrase I find tremendous and terribly precise. It states, “He was not docile to the reign of my voice”. I think that’s what mute silence is, the silence of totalitarian power, of the power that seeks not only to control society and wealth, but also people – to control their minds.

In the novel, a biblical psalm is repeated as a litany, which aptly declares, “The people´s idols are made of silver and gold. They have mouths but cannot speak. They have eyes but cannot see. They have ears but cannot hear”. I think that psalm is very modern.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —How was the process of writing for this book? It was originally suggested by José Luis Cuerda to make it into a movie.

Manuel Rivas: —It was a hybrid process. Sometimes people from the world of cinematography would broach the subject of me possibly writing a script. I was working on a novel that was basically the equivalent to the first part of Todo é silencio, the section about the characters’ childhood and youth, when the possibility of writing a script resurfaced. I was faced with this challenge and so I started working on a script for awhile. I only wrote a draft because I wasn’t convinced by it. Then I told myself that I had to finish the novel.

I remember a prologue to The Third Man where Graham Greene says, “Without a literary text, a script cannot exist”. I think that’s right. Today, I am more convinced than ever. If I hadn´t written the novel, the script would never have been developed.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Nevertheless, a considerable number of your books have been adapted to cinema. Are you happy with the results?

Manuel Rivas: —I greatly admire cinema because, especially today. it’s almost a heroic job that requires resources, complex execution, and teamwork. The job of a writer is not exactly a solitary job, because afterwards, you´re either an open body in which many people coexist or you´re not a writer. They are very different processes, different windows that sometimes look out on the same landscape. Today, if I had to choose, I’d choose the job you do simply with a pencil and a piece of paper.

In any case, it’s absurd to compare two complementary forms of expression, because we are a generation that has grown up with cinema. I find what we call poetry in many movies. When I wrote Butterfly’s tongue, for example, I never thought it would become a film. But now, when I see it, I see that world perfectly reflected. I think it’s more of an intimate relationship, rather than a rivalry, as it´s sometimes made out.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Finally, when do you feel morriña?

Manuel Rivas: —I think that a nostalgic feeling for something you have desired, or still desire, or have lost, is very common. I think that morriña and saudade is something universal. Possibly, what I feel most strongly is not so much nostalgia for the past, but nostalgia for the future. So teño morriña do porvir (I have morriña for the future).

Recommended links

- [Video] Interview with Manuel Rivas at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin, by Alfonso Fernández Cid.

- O máis estraño: A boca da literatura. Manuel Rivas’ blog.

- Manuel Rivas as a journalist. Manuel Rivas in El País.

< List of interviews

Charla con / Talk with… Manuel Rivas

Manuel Rivas nos visita hoy en nuestro Café Literario. Charlará con Alison Ribeiro (UCD, University College Dublin) sobre cine y literatura, novela y poesía o la escritura en lenguas minoritarias.

Manuel Rivas nos visita hoy en nuestro Café Literario. Charlará con Alison Ribeiro (UCD, University College Dublin) sobre cine y literatura, novela y poesía o la escritura en lenguas minoritarias.

Además, escucharemos algunos de sus poemas del libro La desaparición de la nieve (Alfaguara, 2009), que ha sido traducido al inglés por Lorna Shaughnessy en The Disappearance of Snow (Shearsman Books, 2012).

Mañana, día 27 de abril, participará junto a Kirmen Uribe en el Festival Cúirt de Literatura.

Todavía estás a tiempo de enviar tus preguntas para el encuentro digital con Manuel Rivas.

Manuel Rivas in conversation with Alison Ribeiro (UCD) on cinema and literature, novel and poetry or writing in minority languages. We will have the opportunity to listen to some of his poems from the book La desaparición de la nieve (Alfaguara, 2009), which has been translated into English by Lorna Shaughnessy in The Disappearance of Snow (Shearsman Books, 2012).

Tomorrow, 27th April, Manuel Rivas and the Basque writer Kirmen Uribe will participate at the Cúirt International Festival.

You are still in time to send your questions to our digital interview with Manuel Rivas.

Cine / Film Screening: La lengua de las mariposas / Butterfly’s tongue

Como cada miércoles a las seis, el Instituto Cervantes os ofrece una película en su acogedor Café Literario. Esta semana se proyecta La lengua de las mariposas, dentro del ciclo “Una película, un libro” .

Está basada en el relato del mismo nombre y en otro más, Un saxo en la niebla. Ambos forman parte del libro ¿Qué me quieres, amor? de Manuel Rivas.

La historia se sitúa en 1936. Don Gregorio enseñará a Moncho con dedicación y paciencia toda su sabiduría en cuanto a los conocimientos, la literatura, la naturaleza, y hasta las mujeres. Pero el trasfondo de la amenaza política subsistirá siempre, especialmente cuando don Gregorio es atacado por ser considerado un enemigo del régimen fascista. Así se irá abriendo entre estos dos amigos una brecha, traída por la fuerza del contexto que los rodea. La política y la guerra se interponen entre las personas y desembocan, indefectiblemente, en la tragedia.

Manuel Rivas (A Coruña, 1957) es escritor, poeta, ensayista y periodista considerado la voz más sobresaliente de la literatura gallega contemporánea cuya obra está escrita originariamente en lengua gallega. Es autor de varias novelas cortas destacando El lápiz del carpintero (1998), Premio de la Crítica española.

José Luis Cuerda (Albacete, 1947) es director, guionista y productor de cine español. Ha trabajado en Televisión Española realizando más de 500 reportajes y documentales. En su obra vemos una etapa, inaugurada con El bosque animado, caracterizada por un humor surrealista con profundo sabor español. Ha adaptado dos veces la obra de Manuel Rivas, La lengua de las mariposas y Todo es silencio.

A la proyección le seguirá un debate dirigido a todo tipo de público.

As every Wednesday at 6pm, Instituto Cervantes shows a new film in its cosy Café Literario. The film for this week is “The Butterfly´s Tongue”, part of the cinema series “One movie, one book”.

Based on stories from the book ¿Qué me quieres, amor? (What’s up my love?) by Manuel Rivas (A Coruña, 1957).

The story is about a young boy, Moncho who lives in a Galician town and goes to school for the first time and is taught by Don Gregorio about life and literature. At first Moncho is very scared that the teachers will hit him, as that was the standard procedure then, but after his first day at school, he is relieved that Don Gregorio doesn’t hit his pupils. Don Gregorio is unlike any other teacher, and he builds a special relationship with Moncho, and teaches him to love learning. When fascists take control of the town, they round up known Republicans, including Don Gregorio.

Manuel Rivas (A Coruña, 1957) is considered the most prominent contemporary writer, poet, essayist and journalist in Galician language. He is author of several short novels; El lápiz del carpintero is especially noteworthy. The recent film Todo es silencio by director José Luis Cuerda is based in Rivas’ novel Todo é silencio.

José Luis Cuerda (Albacete, 1947) is a Spanish film director, scriptwriter and producer. He has produced over 500 documentaries and reports for Spanish Public Broadcasting. Starting from El bosque animado, his films are notable for the surrealistic humour and a strong Spanish taste.

The screeening will be followed by an open discussion.

Diez años sin José Hierro / Remembering José Hierro

Se cumplen diez años de la muerte del gran poeta español José Hierro. Desde el 19 de abril y hasta finales de año se está llevando a cabo una serie de eventos-homenaje con la idea de ofrecer una visión del autor dinámica, plena e integrada en la actualidad poética y cultural.

Se cumplen diez años de la muerte del gran poeta español José Hierro. Desde el 19 de abril y hasta finales de año se está llevando a cabo una serie de eventos-homenaje con la idea de ofrecer una visión del autor dinámica, plena e integrada en la actualidad poética y cultural.

Mesas redondas, recitales y encuentros en Madrid, Santander o Valencia (ciudades en las que vivió), el descubrimiento de una placa conmemorativa en la calle Fuenterrabía de la capital española (su residencia durante más de 40 años), los denominados Paseos de Hierro (una mirada por Santander desde los ojos del poeta) y recuerdos al poeta en eventos como La Noche en Blanco que se celebrará en Madrid en septiembre, constituyen algunas propuestas a las que también se sumarán sendos actos en los Institutos Cervantes de Belgrado (cuya biblioteca lleva el nombre de José Hierro) y Varsovia (su directora es estudiosa de su figura y fue amiga del poeta). Estos son algunos de los más de veinte actos programados para conmemorar su aniversario.

José Hierro forma parte de la llamada “Generación del medio siglo” cuya poesía contiene rasgos sociales basados en su experiencia en la guerra civil y los difíciles años posteriores, en los que debido a sus actividades clandestinas, llegó a ingresar en prisión. Su obra abarca temas sociales y comprometidos con su realidad social. También nos habla sobre el paso del tiempo y la fuerza de los recuerdos, como puede observarse en su bello Cuaderno de Nueva York y Alegría, dos de sus publicaciones más destacadas.

Su larga carrera como escritor estuvo jalonada por numerosos premios y distinciones entre los que se destacan el Premio Nacional de Literatura 1953, Premio Nacional de la Crítica 1957, Premio Príncipe de Asturias en 1981, Premio Nacional de las Letras Españolas en 1990, Premio Reina Sofía 1995, y el Premio Cervantes de las Letras 1999. Fue Miembro de la Real Academia de la Lengua.

Para los que queráis conocer más sobre este poeta de enorme calidad literaria y humana, podéis consultar en los siguientes enlaces, donde también encontraréis algunos de sus poemas

It is been already ten years since the great Spanish poet José Hierro left us. A wide variety of events-tributes have been organized from the 19th of April until the end of the year with the intention of offering a full, dynamic and integrated vision of the poet in relation to the cultural and poetic scene at the moment.

Round-tables, recitals and meetings in Madrid, Santander or Valencia (cities where he lived), the discovery of a steel sheet in Fuenterrabía St in Madrid (where he resided for over 40 years), the so-called Paseos de Hierro (cultural walks through Santader from the poet´s point of view) and activities related to the poet in events as La Noche en Blanco that will be celebrated in Madrid is September, are some of the different possibilities to commemorate this anniversary. Instituto Cervantes Belgrado (whose library is named after the poet) and Instituto Cervantes Varsovia (its director was a poet´s friend and she is an expert on his work) will be part of the over twenty events organized for this occasion.

José Hierro is part of the “Generación del medio siglo”. His poetry shows social features based on his experiences during the Spanish Civil War and the subsequent difficult years when he was even imprisoned due to his clandestine activities. His work covers social and politically committed issues linked with reality. He also tells us about how time goes and the strength of memories, as we can read in the beautiful “Cuaderno de Nueva York” and “Alegría”, two of his most remarkable works.

His long career as a poet was distinguished with many awards as the National Award of Literature 1953, National Critics´Award 1957, Prince of Asturias Award 1991, National Award of Spanish Arts 1990, Queen Sofia Award 1995, Cervantes Award 1999, member of the Royal Academy of Spanish.

For those who want to know more about this poet of immense literary and human quality, click on the following links:

Entrevista con Ada Salas

Ada Salas: La poesía que lo dice todo no deja espacio de participación al lector

Entrevista con Ada Salas realizada el 23 de abril de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en el recital literario “A dos voces” junto a Leeanne Quinn.

Ada Salas (Cáceres, 1965) es Licenciada en Filología Hispánica por la Universidad de Extremadura. En 1987 recibió el Premio Juan Manuel Rozas de poesía con Arte y memoria del inocente (1988). Su libro Variaciones en blanco (1994) obtuvo el IX Premio Hiperión de poesía. A este título seguirían La sed (1997),Lugar de la derrota y Noticia de la luz, ambos de 2003. En 2005 publicó Alguien aquí: Notas acerca de la escritura poética. Con Esto no es el silencio (2008) obtuvo el XV Premio Ricardo Molina-Ciudad de Córdoba. Un año más tarde, reúne sus cuatro primeros libros en No duerme el animal (Hiperión, 2009). En 2011 publicó el ensayo El margen, el error, la tachadura: de la metáfora y otros asuntos más o menos poéticos, Premio de ensayo Fernando Tomás Pérez González 2010.

Sergio Angulo: —Ada, empezaste a publicar poesía siendo muy joven. ¿Qué motivaciones tenía esa escritora en sus comienzos?

Ada Salas: —Creo que la inmensa mayoría de los poetas empiezan muy jovencitos, casi todos en la adolescencia. La experiencia de la escritura de poesía, en un principio, es una experiencia muy ligada a una necesidad de expresión de los sentimientos. Yo empecé, en ese sentido, como todos. Me contagiaron la pasión por la poesía mis profesores del instituto, a los que les debo muchísimo, pues aquellas lecturas que hacía mi profesor, (entonces era COU, hoy sería segundo de bachillerato), de Juan Ramón Jiménez, de Machado, de Lorca, de Cernuda… Aquello caló, hondamente.

Hice filología española porque yo quería saber más de esos poetas, fundamentalmente. Y empecé a escribir, como digo, por una necesidad de expresión, por una manera de vivir el mundo que se sale por todos los lados, que se desborda, que es la propia edad de la adolescencia. Aquello era, de alguna manera, como escribir un diario pero en verso. Luego eso fue cambiando, y ahora no tiene nada que ver. Ahora es al revés, escribo de una manera completamente distinta.

Sergio Angulo: —Explícanos un poco el tema del silencio en tu poesía.

Ada Salas: —Yo creo que la poesía es un género específico. La poesía es el género más condensado en cuanto a la expresión literaria. La poesía del silencio sería una vuelta de tuerca dentro del género lírico. Sería intentar decir solo lo imprescindible para transmitir un mensaje lo más completo posible con el menor número de elementos posible, porque en poesía, lo que no se dice es tan importante como lo que se dice, y lo que se dice tiene que ser capaz de sugerir lo que no se dice. Entonces se produce un diálogo entre lo presente y lo ausente que a mí me interesa mucho, porque creo que es ese el lugar donde el lector se puede situar. La poesía que lo dice todo no deja espacio de participación al lector.

Sergio Angulo: —¿Hay una manera especial de leer poesía?

Ada Salas: —Sí, claro. Es completamente distinto. Como lectora, la poesía es algo infinitamente más intenso. Yo leo narrativa para descansar. La lectura de poesía es muy exigente. Exige un esfuerzo muy grande del lector, una renuncia a muchas cosas. Generalmente, es una especie de espejo que te sitúa delante de ti mismo, sin piedad, y que te sacude el corazón de manera a veces ardua, que pone al pensamiento contra la espada y la pared.

Uno tiene que saber qué hace cuando se pone a leer poesía. Ahora bien, todo ese esfuerzo se ve infinitamente recompensado porque, aunque es una lectura, como digo, que pide mucho, da muchísimo también. La narrativa te lleva, y es maravilloso dejarse llevar por ella. Al poema lo tienes que sujetar tú. Para mí, no hay lectura mejor que esa.

Sergio Angulo: —¿Crees que la poesía está omnipresente en la literatura?

Ada Salas: —Creo que en general se abusa un poco de esto. Ahora, cuando las cosas son como bonitas o sugerentes, se dice que son poéticas. De un anuncio de publicidad, cuando es un poco soft, dicen «ay, es que es muy poético». Yo estoy en contra de eso por completo, porque a mí lo poético no me parece nada soft. Pero es cierto que hay momentos, hay fragmentos de novelas que sí lo son, precisamente porque suman lo que para mí es la poesía, que es una mezcla de música, emoción y pensamiento. Cuando esos tres elementos se dan en alguna manifestación artística de cualquier tipo, evidentemente ahí hay poesía. La poesía está en el origen de la literatura porque está ligada al canto. Está en cualquier manifestación ritual, está en el origen de cualquier cultura.

Sergio Angulo: —¿Y cómo ves el futuro de la poesia?

Ada Salas: —No lo sé. Tengo amigos que son muy pesimistas al respecto. Yo creo que no se va a acabar nunca, porque creo que siempre ha estado igual de mal. Siempre ha sido una cosa minoritaria y no va a dejar de serlo. Hay épocas en las que la poesía tenía un apoyo del poder, porque vestía tener en la corte poetas de cancionero a tu servicio. Existía una idea del mecenazgo que ahora no existe, y otra relación entre el poder y la cultura. Pero a la poesía no la va a sostener el poder. Esperemos que vaya bien.

Sergio Angulo: —Afirmas que no te interesa la poesía femenina así como no te interesa la poesía masculina, o la poesía homosexual. Dámaso Alonso, al que debemos el nombre de esta biblioteca, decía que a las mujeres españolas que escriben poesía no les gusta la palabra «poetisa». ¿Es la poesía algo neutro?

Ada Salas: —Esto de «poetisa» viene de que a los poetas modernistas, a los seguidores de Rubén Dario, a los de cuarta y quinta fila, los llamaban «poetisos», como un insulto, porque eran como amanerados literariamente, y porque se ponían chalinas. Los llamaban poetisos para hacer un falso femenino, y era un insulto, era una burla. Cuando empezó a haber más mujeres escritoras, seguidoras de las románticas, de Clara Campoamor, etc., se las empezó a llamar «poetisas», y desde entonces, muchas mujeres no querían que se utilizase ese sustantivo para ellas porque tenía esas connotaciones negativas como de afeminado. Porque lo femenino no tiene por qué ser afeminado. Las poetas de los años cincuenta se negaron en redondo a que las llamaran así, «poetisas».

Yo creo que eso ya está superado. A mí me encanta que me llamen poetisa. Me parece que es el femenino gramatical. Quizá si yo hubiera sido de las que hubiera tenido que luchar hace treinta años por el reconocimiento de las mujeres, a lo mejor habría estado por usar poeta. Pero ahora, lo que no soporto es lo de «alumnos y alumnas», «profesores y profesoras»… Me parece un disparate. Va contra la economía del lenguaje.

Sergio Angulo: —Para terminar, y ya que estamos en el Día Internacional del Libro, ¿podrías aconsejarnos algún libro de poesía o de ficción?

Ada Salas: —De ficción, el que estoy leyendo es Oblomov de Goncharov. Es uno de los grandes de la novelística rusa junto con Tolstoi y Dostoievski. Oblomov, el protagonista, es un personaje maravilloso, de estos que no quieren hacer nada. Es el vago por excelencia. Una novela fantástica, realmente. Y de poesía… En concreto, para cualquier persona que se acerque al español, recomiendo a Cernuda, La realidad y el deseo, que reúne toda su obra y que es uno de los grandísimos libros del siglo XX.

Enlaces Recomendados

- [Vídeo] Entrevista realizada a Ada Salas en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín por Sergio Angulo.

- Reseña de Ashes to ashes y de Esto no es el silencio en El Cultural.

- [Audio] Ada Salas en Canal Extremadura.

Interview with Ada Salas

Ada Salas: Poetry that Says Everything Doesn’t Leave Much Room for the Reader’s Participation

Interview with Ada Salas on 23th of April 2012 at the Dámaso Alonso Library of the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin, in association with her participation in the poetry reading “In two voices” with Leeanne Quinn.

Ada Salas (Cáceres, 1965) has a degree in Hispanic Studies from the University of Extremadura. In 1987, she was awarded the Juan Manuel Rozas poetry prize for Arte y memoria del inocente (1988). Her book Variaciones en blanco (1994) won the IX Hiperión poetry prize. She later published La sed (1997) and El lugar de la derrota y Noticia de la luz (2003). Alguien aquí: Notas acerca de la escritura poética, was published in 2005, and with Esto no es el silencio (2008), she won the XV Ricardo Molina-Ciudad de Córdoba Award for poetry. A year later, she compiled her first four books in No duerme el animal (Hiperión, 2009). In 2011, Ada published the essay El margen, el error, la tachadura: de la metáfora y otros asuntos más o menos poéticos received the Fernando Tomás Pérez González Award for essays in 2010.

Sergio Angulo: —Ada, you started publishing poetry when you were very young. What motivated you to write?

Ada Salas: —I think most poets start out very young, mostly in their teens. In the beginning, the experience of writing poetry comes from a need to express your feelings. In that sense, I started like everyone else. I was infected with a passion for poetry by my school teachers, to whom I owe an awful lot. The readings of Juan Ramón Jiménez, Machado, Lorca and Cernuda, that my teacher gave when I was in second year of secondary school, made a deep impression on me.

I studied Spanish Philology, mainly because I wanted to know more about those poets. I started writing, like I said before, because of a need to express myself, to find a way to live in the world that gushes out from every side, that overflows, which is the stage of adolescence itself. It was like writing a diary, but in verse. Later, all that changed, and now it has nothing to do with it. Now it’s the opposite. I write in a completely different way.

Sergio Angulo: —Could you explain silence in your poetry?

Ada Salas: —I think poetry is a specific genre. Poetry is the most condensed genre when it comes to literary expression. So the poetry of silence would be a tweak inside the lyrical genre, where you´re trying to say only what´s essential, to transmit the message as complete as possible with the least amount of elements. Because in poetry, that which is not said is as important as what is said, and that which is said has to be capable of suggesting what is not said. In that way, there’s a dialogue between what´s there and what´s not, that I find very interesting, because I think that’s the place where a reader can situate himself. Poetry that says everything doesn’t leave much room for the reader’s participation.

Sergio Angulo: —Is there a particular way to read poetry?

Ada Salas: —Yes, of course. It’s completely different. As a reader, poetry is something infinitely more intense. I read fiction to have a rest. Reading poetry is very demanding. It demands a great effort from the reader. It requires giving up many things. Generally, it’s a sort of mirror that puts you in front of yourself with no mercy, and squeezes your heart painfully, at times. It puts your mind between a rock and a hard place.

You have to know what you’re doing when you start reading poetry. But all that effort is infinitely rewarded because, even though reading is very demanding, it gives you so much. Fiction transports you somewhere else, and it’s wonderful to be taken away by it. With the poem, you’re the one figuring it out. For me, there’s no better reading than that.

Sergio Angulo: —Do you think poetry is omnipresent in literature?

Ada Salas: —I think it´s sometimes misused. Nowadays, when things are beautiful or thought-provoking, they’re said to be poetic. If a commercial is a little soft, they say, “Oh, it’s so poetic”. I’m completely against that, because I don’t think poetry is soft at all. It’s true there are moments, fragments in a novel that are certainly poetic, precisely because they sum up what poetry is to me, which is a mixture of music, emotion and thought. When those three elements emerge in any other kind of artistic expression, there’s poetry there, obviously. Poetry is at the origin of literature because it’s linked to the singing. It’s in every ritual, at the root of every culture.

Sergio Angulo: —How do you see the future of poetry?

Ada Salas: —I don’t know. I have friends who are very pessimistic about it. I don’t think it’s ever going to end, because it’s always been in a bad way. It´s always been a minority and this will never stop. There were times when poetry was supported by the ruling powers, and poets had an important role in the service of the court. There was this idea of patronage that doesn’t exist now, and another kind of relationship between power and culture. Poetry is no longer supported by power, so let’s hope it does well.

Sergio Angulo: —You say you’re not interested in feminine poetry, just like you’re not interested in masculine poetry or homosexual poetry. Dámaso Alonso, to whom we owe the name of this library, said Spanish women who write poetry don’t like the word poetisa. Is poetry something neutral?

Ada Salas: —The idea of the poetisa comes from the modernist poets. Rubén Darío’s followers, from the fourth or fifth tier, were called poetisos as an insult, because they were quite camp and wore scarves. So they were called poetisos to mock them for being feminine – it was an insult, a snear. Then, when a large number of female writers started publishing, followers of the romantics, of Clara Campoamor etc., were called poetisas. After that, many women didn’t want this noun to be used to describe them, because it had negative connotations of being effeminate. Because feminine doesn’t have to be effeminate. Female poets in the fifties collectively rejected being labelled poetisas.

Now I think all that has been overcome. I love to be called poetisa. I think it’s the grammatical feminine. Maybe, if I´d been one of those women struggling thirty years ago for the recognition of women as being equal to men, I might have been in favour of using poeta. But now, I just can’t stand the issue with alumnos y alumnas, profesores y profesoras… I think that’s nonsense. It’s absurd because it goes against the economy of language.

Sergio Angulo: —Lastly, as we are celebrating World Book Day, could you recommend a book of poetry or fiction?

Ada Salas: —In terms of fiction, I’m currently reading Oblomov by Goncharov. He’s one of the great writers of Russian fiction, next to Tolstoy and Dostoyevski. Oblomov, who is the main character, is a marvellous character. He´s one of those people who doesn’t want to do anything. He’s the slacker extraordinaire. He’s apathy in the flesh, and it’s really a fantastic novel. For poetry, especially for anyone who’s interested in the Spanish language, I would recommend Cernuda, La realidad y el deseo, which is a collection of his work and one of the greatest books of the 20th Century.

Recommended links

- [Video] Interview with with Ada Salas at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin, by Sergio Angulo.

- Review of Ashes to ashes and Esto no es el silencio in El Cultural.

- [Audio] Ada Salas in Canal Extremadura.

Encuentro con Manuel Rivas / Literary encounter with Manuel Rivas

Manuel Rivas charlará con Alison Ribeiro (UCD, University College Dublin) sobre cine y literatura, novela y poesía o la escritura en lenguas minoritarias. Además, escucharemos algunos de sus poemas del libro La desaparición de la nieve (Alfaguara, 2009), que ha sido traducido al inglés por Lorna Shaughnessy en The Disappearance of Snow (Shearsman Books, 2012).

Manuel Rivas (A Coruña, 1957) es escritor, poeta, ensayista y periodista español que escribe en lengua gallega. Algunas de sus obras han sido llevadas a la gran pantalla, siendo una de las más conocidas es La lengua de las mariposas, dirigida por José Luis Cuerda y basada en tres de los relatos del libro ¿Qué me quieres amor? (1996). O Lápis do Carpinteiro, ha sido publicada en nueve países y es, hasta hoy, la obra en gallego más traducida de la historia de la lengua gallega. Sus libros más conocidos en inglés son: El lápiz del carpintero (Carpenter’s Pencil), En salvaje compañía (In the wilderness) y Los libros arden mal (Books Burn Badly).

Como narrador obtuvo, entre otros, el Premio de la Crítica española por Un millón de vacas (1990), el Premio de la Crítica en Gallego por En salvaje compañía (1994), el Premio Nacional de Narrativa por ¿Qué me quieres, amor? (1996), el Premio de la Crítica española por El lápiz del carpintero (1998) y el Premio Nacional de la Crítica en Gallego por Los libros arden mal (2006). Su última novela es Todo es silencio (2010), finalista premio Hammett de novela negra.

Manuel Rivas in conversation with Alison Ribeiro (UCD) on cinema and literature, novel and poetry or writing in minority languages. We will have the opportunity to listen to some of his poems from the book La desaparición de la nieve (Alfaguara, 2009), which has been translated into English by Lorna Shaughnessy in The Disappearance of Snow (Shearsman Books, 2012).

Manuel Rivas was born in A Coruña, Galicia in 1957. He is a Galician writer, poet and journalist. Rivas writes in the Galician language of north-west Spain and is a poet, novelist, short story writer and essayist. Rivas is considered a revolutionary in contemporary Galician literature. Rivas’s book Que me quieres, amor? (1996), a series of 16 short stories, was adapted by director Jose Luis Cuerda for his film, La lengua de las mariposas (Butterfly’s tongue).

His best known books in English are: The Carpenter’s Pencil (1998), In the Wilderness (2004), From Unknown to Unknown (2009) and Books Burn Badly (2010).

Ven a celebrar el Día Mundial del Libro / Come to celebrate World Book Day with us

El día 23 celebramos el Día Mundial del Libro con un recital concurso con nuestros alumnos y un homenaje a la poeta Ada Salas, que recitará sus poemas junto a la poeta irlandesa Leeanne Quinn

¿Estudias con nosotros? Entonces puedes participar en nuestro concurso y ganar un viaje a Málaga (dos noches, incluidos vuelos, con habitación doble con desayuno) o un curso de español gratis.

El 23 de abril es una fecha simbólica para el mundo literario. En 1916, ese mismo día, murieron Cervantes, Shakespeare e Inca Garcilaso de la Vega. Por ello el 23 de abril es la fecha establecida por la UNESCO para celebrar el Día Internacional del Libro y los Derechos de Autor y promocionar la lectura y la edición. Este día se celebra desde 1995.

Para conmemorar este día, el Instituto Cervantes organiza un recital concurso abierto entre los alumnos del centro en homenaje a un poeta contemporáneo. Este año, los textos seleccionados pertenecen a la poeta Ada Salas, a quien le rendimos un merecido homenaje.

Tras el concurso, continuaremos con el recital poético A dos voces, en el que podremos escuchar poemas de Ada Salas (España) y Leeanne Quinn (Irlanda).

Ada Salas nació en Cáceres en 1965. Es Licenciada en Filología Hispánica por la Universidad de Extremadura.

En 1987 recibió el Premio Juan Manuel Rozas de poesía con Arte y memoria del inocente (1988). Su libro Variaciones en blanco (1994) obtuvo el IX Premio Hiperión. En 1997 publicó La sed, y en el 2003 Lugar de la derrota (ambos libros en Hiperión). En ese mismo año aparece Noticia de la luz (Escuela de Arte de Mérida).

En 2005 edita un libro de prosas: Alguien aquí. Notas acerca de la escritura poética (Hiperión). En 2008 Esto no es el silencio (Hiperión) obtiene el XV Premio Ricardo Molina– Ciudad de Córdoba. No duerme el animal (Hiperión, 2009) reúne sus cuatro primeros libros. En colaboración con el pintor Jesús Placencia ha publicado Ashes to Ashes (2010, Editora Regional de Extremadura).

En 2011 ha aparecido su ensayo El margen, el error, la tachadura. Notas acerca de la escritura poética (Diputación de Badajoz), Premio de Ensayo Fernando Pérez 2010. Junto con Juan Abeleira ha traducido A la Misteriosa y Las tinieblas de Robert Desnos.

Leeanne Quinn es oriunda de Drogheda y reside en Dublín. Se licenció en Literatura Inglesa por la University College Dublin en 2001. Un año más tarde finalizó el master en Romanticismo, Modernismo y Postmodernismo de la University College de Cork. Actualmente está realizando un doctorado sobre las novelas de Philip Roth. Su primera antología de poemas, Before you, fue publicada por Dedalus Press en septiembre de 2011.

Are you studying with us? Then you can participate at our Poetry competition and win a trip to Malaga or a 30 hour summer course!

April 23 is a symbolic date for world literature. On this date, in 1616, Cervantes, Shakespeare and Inca Garcilaso de la Vega died. The World Book Day (also known as the International Day of the Book) is a yearly event on April 23, organised by UNESCO to promote reading and publishing. The Day was first celebrated in 1995.

To commemorate this day Instituto Cervantes is organising a recital contest. This year the poems will be by Ada Salas.

If interested, talk to your teacher and get all the information about this event at the reception desk.

After the contest, as part of the celebrations of the World Book Day, Instituto Cervantes Dublin gathers Spanish poet Ada Salas and Irish poet Leeanne Quinn in a In two voices poetry reading.

Ada Salas (Cáceres, Spain, 1965) graduated in Spanish Philology at University of Extremadura. In 1987 she was awarded the Juan Manuel Rozas poetry prize for her book Arte y memoria del inocente (1988). Her book Variaciones en blanco (1994) was awarded the 9th Hiperión Prize. In 1997 she published La sed and in 2003 Lugar de la derrota (both by Hiperión publishing house). On the same year Noticia de la luz was released by Escuela de Arte de Mérida.

In 2005 she publishes the narrative compilation Alguien aquí. Notas acerca de la escritura poética (Hiperión). In 2008 her book Esto no es el silencio (Hiperión) was awarded the 15th Ricardo Molina – Ciudad de Córdoba prize. No duerme el animal (Hiperión, 2009) gathers her first four books. In 2010 she publishes Ashes to Ashes in collaboration with painter Jesús Placencia (Editora Regional de Extremadura).

In 2011 her essay El margen, el error, la tachadura. Notas acerca de la escritura poética (Diputación de Badajoz) was publised and awarded the Fernando Pérez Essay Prize 2010. She has translated A la Misteriosa and Las tinieblas, by Robert Desnos, together with Juan Abeleira.

Leeanne Quinn is originally from Drogheda and lives in Dublin. She studied English Literature in University College Dublin, gaining her B.A. (Hons) 2001. She went on to take an M.A. in Romanticism, Modernism and Postmodernism at University College Cork in 2002. She is currently completing a Ph.D. thesis on the fiction of Philip Roth. Her first collection of poetry, Before You, was published by Dedalus Press in September 2011.

Teatro en la biblioteca / Theater in the library

El pasado 27 de marzo se celebró el Día Mundial del Teatro, una tradición que comenzó en 1961 por iniciativa del Instituto Internacional del Teatro (ITI) y que la Unesco asumió como propia. Se trataba con ella de difundir y dar reconocimiento a esta arte escénica milenaria, que no pierde fuerza a pesar de los incesantes avances tecnológicos y las nuevas alternativas culturales.

El pasado 27 de marzo se celebró el Día Mundial del Teatro, una tradición que comenzó en 1961 por iniciativa del Instituto Internacional del Teatro (ITI) y que la Unesco asumió como propia. Se trataba con ella de difundir y dar reconocimiento a esta arte escénica milenaria, que no pierde fuerza a pesar de los incesantes avances tecnológicos y las nuevas alternativas culturales.

En España, este día volvió a celebrarse imponiendo una bufanda blanca a la estatua de Ramón María del Valle-Inclán, una de los personajes fundamentales de la dramaturgia española, en el Paseo de Recoletos en Madrid.

Su obra más relevante, “Luces de Bohemia” y su protagonista, Max Estrella, son el origen de un recorrido cultural de carácter lúdico por las calles de la capital de España, similar a la celebración del Bloomsday dublinés.

Al recorrido se le llama “La noche de Max Estrella” y fue creada por el autor teatral Ignacio Amestoy Eguigure con el patrocinio del Círculo de Bellas Artes de Madrid.

Durante la noche de Max Estrella se recorren algunas de las calles, plazas, plazuelas y callejones del centro Madrid que de una u otra manera aparecen en la obra de Valle-Inclán, y algunos de los lugares que frecuentaba el autor. Cada una de las estaciones sirve como lugar de encuentro en el que se declaman versos y dramatizan pasajes literarios, se realizan bululús, se da lectura a manifiestos así como a otros textos y parlamentos, e incluso en algunas de las paradas se sirven aperitivos, refrigerios, tentempiés y viáticos.

Este año, con motivo del quince aniversario de esta celebración, el ya tradicional recorrido por las calles, fue sustituido por una maratón teatral en el Círculo de Bellas Artes en torno al genial dramaturgo. La representación de Luces de Bohemia fue el plato principal. Una vez más, Max Estrella, poeta miserable y ciego que vagabundea por un Madrid absurdo, brillante y hambriento de principios del siglo pasado volvió a la vida para recordarnos su última noche en la que tragedia, comedia y esperpento se unen indisolublemente.

Por todo ello, el teatro es nuestro tema del mes de abril en el Instituto Cervantes y la sección de teatro es la destacada en nuestra biblioteca. Ven a conocerla.

The World Day of Theatre took place on the 27th of March. It is an initiative that started in 1961 through the International Institute of Theatre of Unesco to promote this scenic art that keeps going strong despite incessant technological developments and new cultural options.

It was celebrated in Spain by putting once again a white scarf on the statue of Ramón María del Valle-Inclán, one of the key pieces of Spanish drama. His most relevant play, “Luces de Bohemia” and his main character, Max Estrella” are the origin of a cultural route through the streets ofMadrid, it is an event similar to the Dubliner Bloomsday.

The name of the route is “The Max Estrella Night” and it was created by the playwright Ignacio Amestoy Eguigure with the support of the Circle of Fine Arts of Madrid.

It usually takes place during the evening and it goes along streets, squares, small squares and alleys of Madrid city centre rescuing the places, atmospheres and scenes that somehow appear in the play or were frequented by the author. Each stop serves as a meeting point where verses and monologues are recited, parts of the play performed, manifests are given and you can even drink and eat at some of the stops.

This year, as it is the fifteenth anniversary of this celebration, the route which has already become a tradition has been substituted by a theatrical marathon in the Circle of Fine Arts around this brilliant playwright. The performance of “Luces de Bohemia” was the main event. Once again, Max Estrella, miserable and blind poet who wanders around the absurd, shining and starving Madrid from the 19th century, came back to life to remind us about his last night. A night where tragedy, comedy and a grotesque reality tie each other indissolubly.

For all these reasons, theatre is our topic this April at Instituto Cervantes and our theatre section is the highlight in our library. Come to see it!

Audiolibro / Audiobook: Relatos breves de Vicente Blasco Ibáñez.

Hay escritores que nunca pasan de moda; sus obras han sido escritas años atrás, pero nunca quedan obsoletas. Hoy la biblioteca os propone la obra de un autor cuya belleza en la descripción de la realidad muy pocos pueden igualar. Vicente Blasco Ibáñez, escritor, periodista y político, fue un hombre de acción, con una vida intensa entre luchas políticas y exilios, ganándose la admiración tanto de sus amigos como de sus detractores.

Si nunca habéis utilizado nuestros audiolibros, ahora tenéis la oportunidad de probarlo con Relatos Breves , que recoge historias como El monstruo, El rey de las praderas, La noche serbia, La vieja del cinema o Un beso. Descargar el audiolibro es tan sencillo como ir a la sección de “Audiolibros” en nuestra página web e introducir vuestro número de usuario. ¡Listo! ya podéis disfrutar escuchando los relatos de uno de los clásicos españoles del siglo XX.

There are writers who never go out of style; their works were written many years ago, but they do not feel obsolete. Today the library recommends you a work of one author whose beauty in the description of reality is very difficult to compete with, we are talking about the Valentian writer Vicente Blasco Ibáñez. Writer, journalist and polititian, Blasco Ibáñez was a man of action, with an intense life between political fights and exile. He won the admiration of his friends and his detractors as well.

If you have never used our audiobooks service, you have the chance to try it now with Relatos Breves , where he compiles stories as El monstruo, El rey de las praderas, La noche serbia, La vieja del cinema and Un beso. Downloading this audiobook is as easy as going to the section “Audiolibros” on our web site, introduce your user number and…that´s it! You can enjoy listening to one of the most relevant Spanish classics of the 20th century.

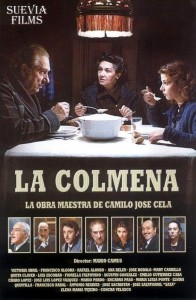

Cine / Film screening: La Colmena

La segunda sesión del ciclo “Un libro, una película” tendrá lugar esta tarde a las seis en el Café Literario. Se proyectará la película “La colmena”, la adaptación de uno de los clásicos recientes de la literatura española. Está basada en la novela homónima del Premio Nobel de Literatura (1989) Camilo José Cela (1916-2002).

La segunda sesión del ciclo “Un libro, una película” tendrá lugar esta tarde a las seis en el Café Literario. Se proyectará la película “La colmena”, la adaptación de uno de los clásicos recientes de la literatura española. Está basada en la novela homónima del Premio Nobel de Literatura (1989) Camilo José Cela (1916-2002).

Autor muy prolífico, trabajó como novelista, periodista, ensayista, editor y conferenciante. Fue académico de la Real Academia Española y recibió numerosos reconocimientos como el Premio Nobel de Literatura en 1989 o el Premio Cervantes en 1995. Fue autor de más de 60 obras y de novelas memorables que también han sido llevadas al cine, destacando La familia de Pascual Duarte y La colmena.

“La colmena” es una historia coral que se inicia, y continúa a veces, en el café La Delicia. El café está siempre repleto de personas que huyen del frío, que se refugian en la charla, en la compañía, y en los sueños… Son sesenta personajes, dentro y fuera del café, que vemos vivir en las calles y en las casas de la ciudad. Son un torrente de gentes que a veces son felices, y a veces, no. Tras ellos, como fondo, el paisaje urbano del Madrid de la posguerra, tan especial, tan distinto, tan sórdido, tan luminoso a veces. El tema principal de la película es el contraste entre los poetas que sobreviven a la miseria bajo el régimen franquista y los ganadores de la guerra, una clase emergente que hace dinero fácil a través de negocios ilegales.

Dirige la película Mario Camus (Santander, 1935). Estudió cine en la Escuela Oficial después de pasar por la facultad de derecho. Destaca por su maestría en la dirección de adaptaciones cinematográficas al cine.

A la proyección le seguirá un debate dirigido a todo tipo de público a cargo del profesor Juan Pablo Auñón.

The second session of the cinemas series “One book, one film” will take place today at 6pm in the Café Literario. It will be screened the film “La colmena”, the adaptation of one of the recent classics of the Spanish Literature. It is based on a 1943 book of the same title by the Nobel Price in Literature (1989) Camilo José Cela (1916-2002).

He was a prolific novelist, journalist, essayist, editor and lecturer. He was appointed member of the Royal Spanish Academy (Real Academia Española). Amongst some of the numerous awards he received are the 1989 Nobel Prize in Literature or the Cervantes Prize in 1995. He published over 60 works and memorable novels that were adapted to the cinema like La familia de Pascual Duarte y La colmena.

“La Colmena” is an ensemble film that features the comings and goings of a wide variety of characters, all trying to survive in a poverty-stricken Madrid during World War II. Rather than feature any single story line, these people from all walks of life cross paths almost randomly as they come to a café to sip their one cup of coffee and work on a book, or pick up a prostitute, or get their shoes shined, or play billiards, or just warm themselves on a cold winter’s day. The main theme of the film is the contrast between the poets, surviving close to misery under the Franco’s regime, and the winners of the war, the emerging class of the people that makes easy money with illegal business.

Mario Camus (Santander, 1935) studied law followed by cinema studies at the Spanish Official Cinema

School. He belongs to the so called “New cinema generation” together with Saura and Martín Patino amongst others. He excels in his work as director of screen adaptations.

The screening will be followed by an open discussion moderated by the teacher Juan Pablo Auñón.

Entrevista con Antonio Praena

Antonio Praena: Perder puede ser ganar. Menos es más.

Entrevista con Antonio Praena realizada el 13 de marzo de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en el recital literario “A dos voces” junto a Judith Mok.

Antonio Praena Segura (Purullena, Granada, 1973) es dominico y poeta. Actualmente se dedica a la enseñanza e investigación teológicas en la Facultad de Teología San Vicente Ferrer de Valencia. Sus primeros poemas publicados aparecieron en antologías colectivas. En 2003, recibió el Accésit del Premio de Poesía Iberoamericana Víctor Jara por su libro Humo verde. Tres años después, Poemas para mi hermana fue reconocido con el accésit del prestigioso premio Adonais. En 2011 obtuvo el Premio Nacional de Poesía José Hierro por su obra Actos de amor. Su último poemario, Yo he querido ser grúa muchas veces, recibió el Premio Tiflos de poesía en 2013.

Sergio Angulo: —Antonio, ¿por qué escribes y por qué poesía?

Antonio Praena: —Yo creo que la poesía es algo que no se elige. No tengo conciencia de haber decidido en algún momento empezar a hacer poesía. Es algo que ha aparecido siempre, desde que yo me recuerdo a mí mismo, y que en algún momento determinado resultó ir más en serio de lo que yo pensaba. Apareció un librito, apareció algún premio y te dices: «¿Voy en serio o no voy en serio?» Y desde ese momento, como que quedas enganchado. Por ahora la veta no se ha acabado. Yo creo que la poesía, cuando ella misma quiera acabarse, se irá sola.

Sergio Angulo: —En este tiempo que vivimos, en el que impera lo breve, lo económico, lo compacto y lo rápido, ¿por qué la poesía sigue siendo el hermano pequeño de la literatura, el que menos lectores atrae?

Antonio Praena: —Aunque sea la que menos lectores atrae, y siempre se ha dicho aquello de que es para una inmensa minoría, sin embargo, por lo que conozco en el mundo literario, todo escritor lleva dentro de sí una vocación poética. Sabemos que la espinita de Cervantes era la poesía, precisamente. Para algunos es de minorías, pero sin embargo, es como un límite del lenguaje, la esencia del lenguaje, el centro del lenguaje o el epicentro de las palabras, de la intensidad, del ritmo, de las imágenes. Es pequeñita pero muy importante.

Yo creo que el tiempo en el que estamos, para conectar con el principio de tu pregunta, vuelve a retomar la poesía. Estos días, con los meses anteriores, el año pasado, con los movimientos del 15M, por ejemplo, a mí me asombraba encontrar nuevamente poesía. Esa especie de renacer de una nueva poesía social, eslóganes que eran versos, que a veces podrían haber estado firmados incluso por un Blas de Otero. Yo creo que la poesía nunca morirá, y que en los tiempos de crisis la poesía renace con fuerza. Una prueba es el vigor que tiene la poesía en español en estos momentos en el mundo.

Sergio Angulo: —En tu libro Poemas para mi hermana, que es un libro, entre otras cosas, sobre la pérdida, hay un verso muy potente que dice: «Si quieres ser feliz, piérdelo todo». ¿Vivimos acaso en una época con demasiados apegos?

Antonio Praena: —Creo que hay que leer en positivo las consecuencias negativas de la crisis económica que hemos vivido. Quizás darnos cuenta de que para sustentar una vida, una existencia, son más fundamentales otros valores: los amigos, las relaciones, la familia. Y precisamente en sociedades en donde ha habido pobreza durante mucho tiempo, como puede haber sido la irlandesa, o la española, el ser humano se ha dado cuenta de que es más valioso el dar, y que se puede vivir con menos. Nos hacemos más compasivos y buscamos otros recursos en nuestro interior y en el corazón de las personas que nos sostienen, que nos sujetan.

Yo creo que ese verso, «si quieres ser feliz, piérdelo todo», que es un poco budista, es una poética y a la vez un axioma espiritual. Creo que indica eso, que se puede y se debe vivir sabiendo qué es fundamental en la vida y qué no lo es, qué es lo que nos hace ser felices y qué es lo que no, y por ende, cuáles son todas aquellas cosas que nos atan, que nos hacen perder nuestra libertad y nos llenan la vida de cosas que al final nos hacen infelices. Perder puede ser ganar. Menos es más.

Sergio Angulo: —¿Qué te parece Internet con esta sobredosis de información, no siempre veraz? En Internet,Poemas para mi hermana aparece como si fuera resultado de la trágica muerte de tu hermana, que no es real, alguien la inventó.

Antonio Praena: —Un libro, una vez que parte de uno mismo, ya no nos pertenece. De alguna forma le pertenece al lector. Siempre he pensado que un poema lo concluye el lector y que publicar tiene también mucho de desposesión.

Efectivamente, en el libro hay una muerte. Quizás una muerte amorosa, o quizás la muerte de muchas personas con las que me he encontrado en mi vida, y que de alguna manera queda literaturizada en Poemas para mi hermana. El que alguien lo entienda así, como una muerte real, me parece que es un logro. La literatura no puede funcionar únicamente como el periodismo, no da cuenta de los acontecimientos de manera cronológica y demostrable, sino que nos abre las puertas a otros mundos y a otras profundidades. En Poemas para mi hermana hay un trayecto de amor y de muerte que ha encontrado el recurso de la poesía para expresarse.

Sergio Angulo: —Y si volvemos a los orígenes de la poesía, donde obviamente no había Internet, pero sí había frailes poetas, como Gonzalo de Berceo, vemos que hay ciertos versos que reflejan de alguna manera una vida bohemia o noctámbula que a veces se atribuye a la poesía.

Antonio Praena: —¡Una vida de crápula!

Sergio Angulo: —¿Qué hay de crápula y cómo lidia Antonio Praena con esa faceta de la poesía?

Antonio Praena: —Mis amigos pertenecen al mundo de la farándula y yo me desenvuelvo en el contexto normal de una persona más o menos joven del siglo XXI. Mi forma de amar, de entender y de encontrar también a Dios, lo religioso, es en el mundo. Sé que es más, que es distinto, que es diferente, pero creo absolutamente que el amor a Dios es una mentira absoluta si no pasa por el amor a las personas concretas, con nombres, con rostros, con historias, con desgarros, con aspiraciones, con sueños bien concretos. En Actos de amor está ahí precisamente esa idea.

En la presentación del libro, cuando recibí el Premio José Hierro, alguien dijo que es un libro heterodoxo porque aparece el sexo y muchas otras historias. Sin embargo, todo ello está relacionado con una llamada a la trascendencia. Se habla con Dios y se habla con los hombres a la vez. Me parece que es así, que es natural. No soy en ese sentido espiritualista ni platónico. Creo en la realidad. Me encuentro con un Dios vital, un Dios de la amistad, un Dios de la esperanza del hombre, real, que quiere hacer a las personas felices y que sean felices en la vida de cada día, y esa vida hay que vivirla.

Sergio Angulo: —¿Qué le dice Antonio Praena a un joven que quiere ser poeta?

Antonio Praena: —No sé si es la respuesta adecuada o políticamente correcta, pero yo le diría que, en primer lugar, le de mucha importancia a los aspectos formales. Hoy en día, que se escribe mucho y hay mucha poesía en Internet, se necesita detenerse primero en los aspectos formales, pasar mucho tiempo entrenando la métrica, el ritmo, siendo muy riguroso, porque esa es la única manera de conseguir que un poema sea arte. No sé si los míos lo son o no, pero sé que la diferencia entre un diario con sentimiento y un puñado de intenciones, y una obra literaria con voluntad de comunicación y de publicación, pasa por el rigor formal. Cuando se tiene el rigor formal, como un bailarín que ha entrenado su cuerpo y asimilado los movimientos, se tiene toda la libertad para decir lo que se quiera y como se quiera. Por eso, a un joven le pediría que leyera mucho y le diera importancia a ese rigor.

Sergio Angulo: —Para terminar, recomiéndanos un libro. Un libro de poesía contemporánea.

Antonio Praena: —El último que he leído y en el que estoy aún es Mundo dentro del claro, de Vicente Gallego, que me está gustando mucho. Vicente Gallego es un poeta al que admiro, tanto su poesía de la experiencia como estos giros últimos que está dando. Me parece que es un libro de gran madurez. También cualquier libro de Juan Antonio González Iglesias, o de José Mateos, que son para mí referentes, o de Antonio Colinas. Todos ellos me parecen importantes.

Enlaces recomendados

- [Vídeo] Entrevista realizada a Antonio Praena en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín por Sergio Angulo.

- El atril. Blog de Antonio Praena.

- Reseñas de Poemas para mi hermana en Poesía digital y de Actos de amor en La pluma de barro.

< Listado de Entrevistas

Interview with Antonio Praena

Antonio Praena: Losing Can Be Winning. Less is More

Interview with Antonio Praena on 13th March 2012 at the Dámaso Alonso Library of the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin, in association with his participation in the literary reading “In two voices” with Judith Mok.

Antonio Praena Segura (Purullena, Granada, 1973) is a Dominicon priest and a poet. He is currently teaching and carrying out research in the Faculty of Theology at San Vicente Ferrer in Valencia. His first published poems appeared in collective anthologies. In 2003, he received the Víctor Jara Award for Iberoamerican poetry for Humo verde (2003). Three years later, Poemas para mi hermana was runner-up for the prestigious Adonais Award for poetry. In 2011, he received the José Hierro national poetry award for his work Actos de amor. His latest collection of poems, Yo he querido ser grúa muchas veces, won the Tiflos Award for poetry in 2013.

Sergio Angulo Bujanda: —Antonio, why do you write, and why poetry?

Antonio Praena: —I think poetry is something that is not chosen. I don’t remember consciously deciding at some point to start making poetry. It’s something that has always been there, for as long as I can remember and, at some point, it ended up being more serious than I thought. A little book was published and well, an award was won and you say to yourself, “Am I serious or not?” From that moment on, you are hooked and it’s been going well so far. I think when the poetry comes to an end, it will leave on its own.

Sergio Angulo Bujanda: —In current times, where brevity, economy, and speed reign, why is poetry still the little brother of literature, the one that attracts less readers?

Antonio Praena: —Despite attracting fewer readers (it’s always been said it’s for an immense minority) from what I know of the literary world, every writer carries a poetic vocation inside themselves. We know that Cervantes had a thing for poetry. For some it’s for minorities, but even so it’s like the limit of language, or the essence of language, the centre of language, the epicentre of words, of intensity, of rhythm, of images. What I mean is, it’s small but very important.

I think the times we’re living in, to go back to the beginning of your question, is conducive to taking up poetry again. Last year, with the 15M movements, for example, I was surprised to find poetry again. The rebirth of a new type of social poetry, slogans that are verses, could even be endorsed by the likes of Blas de Otero. I think poetry will never die, and in times of crisis, poetry re-emerges with new strength. The vigour that Spanish poetry possesses today is proof of that.

Sergio Angulo Bujanda: —In your book Poemas para mi hermana, which is a book, about loss, amongst other things, there’s a very potent verse that stands out. It states, “Si quieres ser feliz, piérdelo todo” (“If you want to be happy, lose everything”). Do we live in times with too many attachments? Do we create needs or dependencies we may not actually need?

Antonio Praena: —I think we have to regard the negative consequences of the economic crisis we are living through in a positive way. We must realise that to sustain an existence, other supports and values are fundamental – friends, relationships and family. Particularly in societies where there has been poverty for a long time, as there has been in Ireland and Spain, people realise that giving is more valuable and it’s possible to live with less. We become more compassionate and we look for other means inside ourselves, and inside the hearts of the people close to us, who support us.

I think the line, “If you want to be happy, lose everything” is a little Buddhist, a little poetic, but at the same time, it´s a spiritual axiom. I think it indicates that you can and you must live knowing what is fundamental in life, and what isn’t, what makes us happy and what doesn’t – all those things that tie us down, that make us lose our freedom and fill our lives with things that, in the end, make us unhappy. Losing can be winning. Less is more.

Sergio Angulo Bujanda: —What do you think of the Internet and this overdose of information that´s not always as truthful as it seems? On the Internet, it says that Poemas para mi hermana was related to the tragic death of your sister that, but it´s not true, someone made it up.

Antonio Praena: —I think a book, once it leaves us, doesn’t belong to us anymore. Somehow, it belongs to the reader. I have always thought that a poem is completed by the reader, and publishing has a lot to do with letting go.

It´s true there´s a death in my book. Possibly a romantic death, or the death of many people I have met in my life, and in some way, this is given the literary treatment in Poemas para mi hermana. The fact that someone understands it like that and talks about it, giving an impression of truthfulness, this seems like an achievement to me. Literature doesn´t work like journalism, it doesn’t recount events in a chronological and accountable manner, it opens worlds and other depths, and that’s where the journey of love and death takes place and where it finds the means of expressing itself.

Sergio Angulo Bujanda: —If we go back to the origins of poetry, when obviously there was no internet, there were poet monks, like Gonzalo de Berceo. Some verses reflect a bohemian or secret life that is sometimes attributed to poetry.

Antonio Praena: —The life of a libertine!

Sergio Angulo Bujanda: —Are there aspects of self-indulgence and how does Antonio Praena deal with that aspect of poetry?

Antonio Praena: —Well, I have famous friends and in my house it’s fine. I mean, I try to live the normal life of a young person in the 21st Century, My way of loving, of understanding, and also finding God, the religious side of life, is in this world. I know it’s more than that, it’s different, but I absolutely believe the love for God is a complete lie, unless it´s channeled through our love for specific people, with names, with faces, with stories, with tears, with aspirations, with very concrete dreams.

In Actos de amor, this particular idea exists. At the presentation, when I received the José Hierro award, someone said, “It’s an unorthodox book”, because of the theme of sex, amongst other things But all these things are related to transcendence. You talk to God and you talk to people at the same time. I think that’s how it is, that it’s natural. I’m not spiritualistic or idealistic in that sense. I believe in reality. I find God essential, a God of friendship, a God of hope for men, who wants to make people happy, and for them to be happy in life, in the everyday life. This life must be lived.

Sergio Angulo Bujanda: —What would Antonio Praena say to a young person who wants to be a poet?

Antonio Praena: —I don’t know if it´s an appropriate answer, or if it’s politically correct, but I would tell him that firstly he has to give great importance to the formal aspects. Nowadays, when so much is written and there is so much poetry on the Internet, it’s necessary to study the formal aspects and spend a long time training the metrics, the rhythm, being rigorous, because it’s the only way of making a poem into art. I don’t know if mine are or aren’t, on a bigger or smaller scale, but the difference between a diary with feeling and a bunch of good intentions and a literary work, with the intent for communication and publication, goes through the formal rigorousness. When you have the formal rigorousness, like a dancer who has trained his body and learned the movements and formed the muscles, then you can have all the freedom to say whatever you want, the way you want to, to innovate, to do anything. I would recommend a young poet to read a lot and give importance to that rigour. Later, the time to do all the experiments you want will come.

Sergio Angulo Bujanda: —Lastly, could you recommend a book of contemporary poetry?

Antonio Praena: —The last book I read, and am still reading, is Mundo dentro del claro by Vicente Gallego. I’m enjoying it very much. Vicente de Gallego is a poet I admire, for his poetry of experience as well as for these new turns he’s making. I think it’s a book of great maturity. And also, any book by Juan Antonio González Iglesias or by José Mateos, who inspire me, or by Antonio Colina – I think they are all important.

Recommended links

- [Vídeo] Interview with Antonio Praena at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin, by Sergio Angulo.

- El atril. Antonio Praena’s blog.

- Reviews of Poemas para mi hermana in Poesia digital and of Actos de amor in La pluma de barro.