Blog del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín

Torre Martello

Manuel Rivas en nuestra biblioteca / Manuel Rivas in our library

Manuel Rivas (A Coruña, 1957) nos visitó el pasado mes de abril y nos concedió esta entrevista que ahora os ofrecemos en video.

Manuel Rivas es escritor, poeta, ensayista y periodista español que escribe en lengua gallega. Algunas de sus obras han sido llevadas a la gran pantalla, siendo una de las más conocidas La lengua de las mariposas, dirigida por José Luis Cuerda y basada en tres de los relatos del libro ¿Qué me quieres amor? (1996). O Lápis do Carpinteiro, ha sido publicada en nueve países y es, hasta hoy, la obra en gallego más traducida de la historia de la lengua gallega. Sus libros más conocidos en inglés son: El lápiz del carpintero (Carpenter’s Pencil), En salvaje compañía (In the wilderness) y Los libros arden mal (Books Burn Badly).

Como narrador obtuvo, entre otros, el Premio de la Crítica española por Un millón de vacas (1990), el Premio de la Crítica en Gallego por En salvaje compañía (1994), el Premio Nacional de Narrativa por ¿Qué me quieres, amor? (1996), el Premio de la Crítica española por El lápiz del carpintero (1998) y el Premio Nacional de la Crítica en Gallego por Los libros arden mal (2006). Su última novela es Todo es silencio (2010), finalista premio Hammett de novela negra.

Manuel Rivas (A Coruña, 1957) visited us last April and answered to our questions in this interview.

Manuel Rivas was born in A Coruña, Galicia in 1957. He is a Galician writer, poet and journalist. Rivas writes in the Galician language of north-west Spain and is a poet, novelist, short story writer and essayist. Rivas is considered a revolutionary in contemporary Galician literature. Rivas’s book Que me quieres, amor? (1996), a series of 16 short stories, was adapted by director Jose Luis Cuerda for his film, La lengua de las mariposas (Butterfly’s tongue).

His best known books in English are: The Carpenter’s Pencil (1998), In the Wilderness (2004), From Unknown to Unknown (2009) and Books Burn Badly (2010).

Rosalía de Castro: autora del mes de agosto

Rosalía de Castro (Santiago de Compostela, 24 de febrero de 1837-Padrón, 15 de julio de 1885) es nuestra autora del mes en agosto. Muchos de sus estudiosos consideran que a partir de su figura se inicia la poesía moderna por su concepción del verso, su ritmo interior y su música. En pocos casos encontramos una poesía que trate los elementos naturales, la melancolía y el misterio con tanta sensibilidad y perfección.

Hija natural de Teresa de Castro, perteneciente a una noble familia gallega y de un sacerdote, nunca superó del todo la crisis desencadenada cuando averiguó su procedencia ilegítima. Su primer libro de versos, La flor, es el comienzo de una obra en la que el amor desgraciado y la denuncia social serán temas recurrentes. Su importante producción poética se encuadra dentro del más claro y melancólico romanticismo. Además, colaboró de forma decidida en el renacimiento de la lengua gallega.

Poseedora de un gran espíritu céltico, en su obra la vida y la muerte van de la mano y se confunden. El mar siempre ejerció una gran influencia en su obra. En su novela La hija del mar, resulta evidente su simbología como sugestiva invitación a la muerte, el lecho ideal en el que descansar de las desdichas de la vida. Célebres son sus últimas palabras antes de morir: “Abrid la ventana, que quiero ver el mar”, a pesar de que desde su casa de Padrón eso no era posible.

Importante es también su labor como precursora del papel activo de la mujer en la sociedad y en la literatura. En su obra se transluce una progresiva liberarización y una toma de conciencia de su rol como mujer valiente, culta y representativa de la literatura en español y en gallego. Llegó a afirmar que escribía porque “a las mujeres todavía no se les permite escribir sobre lo que hacen y lo que sienten”.

Fue autora de una obra notable en prosa pero sin duda donde sobresalió fue en el campo de la poesía a través de las que se consideran sus obras claves. Cantares Gallegossupone una reivindicación de la lengua gallega a través de unos poemas de gran altura artística. Follas Novases una obra profunda con un uso impecable del símbolo. En las orillas del Sar está impregnada de un tono trágico acorde a las circunstancias en las que la autora se movió durante toda su vida.

Aquí tenéis uno de sus poemas más bellos y sin duda el más estudiado, Negra sombraEsperamos verte en la biblioteca donde tenemos a tu disposición la obra de esta magnífica escritora.

Cando penso que te fuches,

negra sombra que me asombras,

ó pé dos meus cabezales

tornas facéndome mofa.

Cando maxino que es ida,

no mesmo sol te me amostras,

i eres a estrela que brila,

i eres o vento que zoa.

Si cantan, es ti que cantas,

si choran, es ti que choras,

i es o marmurio do río

i es a noite i es a aurora.

En todo estás e ti es todo,

pra min i en min mesma moras,

nin me abandonarás nunca,

sombra que sempre me asombras

Advenimiento: Audiolibro de la semana / Audiobook of the week

¿Disfrutasteis del audiolibro de la semana pasada? ¿Os gustan las historias de terror? Pues con ellas seguimos, porque el audiolibro de esta semana también se adentra en el terreno de lo fantástico, el misterio y el horror. Si os da miedo la oscuridad, por favor, no descarguéis este audiolibro.

La historia: Advenimiento es un viaje al infierno… o quizás la salida de él. Adrián Montes es psicoantropólogo. Lo llaman para que se una al equipo que investiga un nuevo advenimiento: la aparición, en una vieja casa, de dos semiesferas ocupadas por un hombre y una mujer ¿Una aparición divina? ¿Una manifestación del maligno… o de algo peor?

Advenimiento es una historia de muerte más allá del amor.

El autor: Adolfo Camilo Díaz López es un escritor, dramaturgo y gestor cultural asturiano. Como escritor, destaca como autor de textos teatrales y de novelas cortas, y ha ganado algunos de los premios más prestigiosos de la literatura asturiana, como el Premio Xosefa de Xovellanos en dos ocasiones y el de novela corta de la Academia de la Lengua Asturiana. Obtuvo la licenciatura en Historia en la Universidad de Oviedo.

¿Did you enjoyed last week audiobook? Do you like scary stories? Good, because this week audiobook also delves into the realm of fantasy, mystery and horror. If you afraid of the dark, please do not download this file.

The story: Advenimiento is a journey to hell. Adrian Montes is psicoantropologist. He is asked to join the team investigating a new mistery: the appearance of two hemispheres occupied by a man and a woman in an old house. A divine apparition? A manifestation of evil … or something worse?

Advenimiento is a story of love beyond death.

The author: Adolfo Camilo Diaz Lopez is a writer, playwright and cultural manager from Asturias, Spain. As a writer, stands out as the author of dramatic texts and short stories, and has won some of the most prestigious awards of Asturian literature. He graduated in History at the University of Oviedo.

Audiolibro de la semana | Audiobook of the week: Bilis negra

Para esta semana te proponemos una nueva novela en audio, una novela de misterio, perfecta para estos días de lluvia que insisten en acompañarnos. El título es Bilis negra, de la novelista Samantha Devin. Puedes descargarla ahora mismo y escucharla en cualquier reproductor de MP3. La tienes a un solo clic de distancia.

Para esta semana te proponemos una nueva novela en audio, una novela de misterio, perfecta para estos días de lluvia que insisten en acompañarnos. El título es Bilis negra, de la novelista Samantha Devin. Puedes descargarla ahora mismo y escucharla en cualquier reproductor de MP3. La tienes a un solo clic de distancia.

La historia: Simon Bughin sospecha que detrás del inesperado suicidio de su hermana se esconde una secta satánica. Sus investigaciones le llevan a Shimts, un pequeño pueblo del norte de Escocia.

Allí conoce a Max, un joven dibujante de cómics reservado y tímido, que ha llegado hasta ese apartado lugar porque su madre también se acaba de suicidar sin razón aparente. Los dos están alojados en el único hotel del pueblo, un antiguo castillo escocés regentado por una extravagante ninfómana.

Ambos buscan al mismo hombre: un prestigioso psiquiatra, amante de las ciencias ocultas, que parece ser responsable de ambas muertes. Simon y Max descubren que el pueblo y sus habitantes esconden un secreto que compromete su propia visión de la realidad.

The story: Simon Bughin suspects that there is a satanic cult behind her sister´s unexpected suicide. His research takes him to Shimts, a small village in the north of Scotland. There he meets Max, a young and shy cartoonist who has just arrived to that far away place because his mother has just commited suicide as well.

Both are staying at the only hotel in the village, an old Scottish castle run by an odd nymphomaniac. They are both looking for the same man: a prestigious psychiatrist, fan of the occult who seems to be responsible for both deaths. Simon and Mak find out that the village and its inhabitants hide a secret that compromises their own vision of reality.

The author: Samantha Devin is a Spanish writer living in London. She published several short stories in prestigious anthologies before publishing her first novel, Bilis negra (2004). She has cooperated with several media as London Magazine. Devin published her second novel in 2006, Arcadia which is a modern tragedy that confirms her talent as a horror writer.

Feliz Bloomsday / Happy Bloomsday

Juan Cruz nos visitó el pasado día 11 de junio. Siempre generoso, durante esta semana ha dedicado dos entradas de su blog a Irlanda, especialmente a Dublín, a Joyce, a Cervantes, y a lo vivido aquí durante sus visitas al Instituto.

Ya lo decía en su primera entrada: los irlandeses “reirán hasta Bloomsday y después”. Lo vimos muy claro durante el partido que enfrentó a Irlanda con España. La afición irlandesa no dejó de cantar, sonreír y animar a su equipo a pesar de la derrota, como siguen haciendo durante la crisis, cantando los hermosos acordes de The Fields of Athenry.

¿Seremos nosotros también capaces de seguir sonriendo? Afortunadamente, tenemos muchas cosas en común con Irlanda. También ese espíritu burlón que nos hace fuertes ante la adversidad y nos anima a reirnos hasta de nuestra propia sombra. Feliz Bloomsday.

Reirán hasta Bloomsday y después / Juan Cruz

El ministro irlandés de Educación es calvo y corpulento, como una cama sin hacer, que decía Sean Connery en La Casa Rusia. Se llama Roairi Quinn y es arquitecto; a él se debe que los nacionalistas ultrarreaccionarios de Dublín no acabaran con los vestigios del estilo georgiano, que consideraban una agresión al gusto patrio. Y por eso hoy Dublín sigue siendo la ciudad que amaron, y odiaron, Beckett y Joyce, quienes, como escribió el primero, jamás se fueron de esta isla aunque desarrollaran su vida y su literatura de uñas con la vida en otras geografías muy distantes.

Bloomsday / Juan Cruz

El mejor homenaje a un escritor es leerlo. Hoy se celebra el Bloomsday, el día en que Leopold Bloom, el célebre personaje de James Joyce, recorre como Ulises el camino que en Dublín tantas décadas después marca la más impresionante carrera que la imaginación le prestó a la literatura y a la vida.

Juan Cruz visited us last June 11. Always generous, this week he has devoted two of his blog posts to Ireland, especially to Dublin, Joyce, Cervantes, and to the experiences he lived here during his visits to the Instituto Cervantes.

He already said it in his first post of the week: Irish people will laugh to Bloomsday and later.” We saw it very clear during the football match between Ireland and Spain. Irish fans never stopped singing, smiling and cheering their team despite the defeat, as they still do during the crisis, singing the beautiful chords of The Fields of Athenry.

Will we also be able to keep smiling? Fortunately, we have many things in common with Ireland. Also that spirit that makes us strong in adversity and encourages us to laugh even of ourshelves. Happy Bloomsday.

Mario Vargas Llosa y Seamus Heaney en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín / Mario Vargas Llosa and Seamus Heaney at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin

El pasado lunes, antes del encuentro literario que tuvo lugar en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con Mario Vargas Llosa y Juan Cruz, dos grandes de la literatura, dos premios Nobel, se reunieron en la Biblioteca del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín.

En el video, Mario Vargas Llosa y Seamus Heaney intercambian comentarios sobre su obra y sobre su experiencia en Estocolmo, adonde viajaron para recibir el galardón de la academia sueca.

La velada literaria tuvo lugar a continuación de este encuentro, con motivo de la presentación en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín de la traducción al inglés de El sueño del celta (The dream of the Celt), la última novela de Mario Vargas Llosa.

Mario Vargas Llosa, Premio Nobel de Literatura en 2010, Premio Cervantes en 1994 y Premio Príncipe de Asturias de las Letras en 1986, es uno de los más importantes novelistas y ensayistas contemporáneos. Nacido en Arequipa, Perú, en 1936, viajó a España en 1959 gracias a una beca para realizar un doctorado en la Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

Ese mismo año, vio la luz su primera publicación, Los jefes, un conjunto de cuentos que obtuvieron el premio Leopoldo Alas. Sin embargo, no sería hasta la década de 1960 cuando publicó tres de las obras que lo lanzaron a la fama: La ciudad y los perros (1962), La casa verde (1965) y Conversación en La Catedral (1969). En 2010, tras recibir el Premio Nobel, publicó El sueño del celta, en la que se cuenta la peripecia vital de un hombre de leyenda: el irlandés Roger Casement, uno de los primeros europeos en denunciar los horrores del colonialismo.

Last Monday, before the literary evening at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin with Mario Vargas Llosa, and Juan Cruz , two literary great writers, two Nobel laureates, gathered at the Instituto Cervantes Library in Dublin.

In this video, Mario Vargas Llosa and Seamus Heaney exchange comments about their work and their experience in Stockholm, when they traveled there to receive the award from the Swedish Academy.

The literary evening ensued on the occasion of the presentation of the English translation of El sueño del celta (The dream of the Celt) at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin.

The dream of the Celt is Mario Vargas Llosa’s latest novel, where he tells the life story of a legendary man: the Irish Roger Casement, one of the first Europeans to denounce the horrors of colonialism.

Mario Vargas Llosa, Nobel Prize in Literature 2010, Cervantes Award 1994, Príncipe de Asturias de las Letras Award 1986, is one of the most significant contemporary novelists and essayists.

Mario Vargas Llosa was born in 1936 in Arequipa (Peru). He travelled to Spain in 1959 thanks to a bursary to complete a doctorate at Complutense University in Madrid.

On the same year, he published his first work, Los jefes, a compilation of stories. It is not, however, until the 60´s when he published three of the works that launched him to fame: La ciudad y los perros in 1962, La casa verde in 1965 and Conversación en La Catedral in 1969.

Following a period of intense political activity, he returned to writing in 1993 with his book of memoirs El pez en el agua. In 2010, he published The dream of the celt.

El hombre que se atrevió a soñar / The man who dared to dream

Hoy hemos recibido a Mario Vargas Llosa en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín. El premio Nobel de Literatura 2010 ha charlado con Juan Cruz ante más de doscientas personas acerca de su última novela, El sueño del celta y su protagonista, Roger Casement.

Hoy hemos recibido a Mario Vargas Llosa en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín. El premio Nobel de Literatura 2010 ha charlado con Juan Cruz ante más de doscientas personas acerca de su última novela, El sueño del celta y su protagonista, Roger Casement.

Durante la velada, también hubo tiempo para reflexionar acerca de la banalización de la cultura, a propósito de la reciente publicación del libro de ensayo de Vargas Llosa que lleva por título La civilización del espectáculo, y por supuesto para saludar y conversar con su viejo amigo, Seamus Heaney.

El pasado fin de semana se publicó en el Irish Times una elogiosa crítica de El sueño del celta, publicado en inglés por Faber and Faber. El resumen de la conferencia que retransmitimos a través de twitter se puede consultar en: http://storify.com/icdublin/en

Tonight Instituto Cervantes Dublin hosted Mario Vargas Llosa. Over 200 guests listened to the laureate of the 2010 Nobel Prize in Literature chat to Juan Cruz about his recent novel “The Dream of the Celt” and its protagonist Roger Casement.

During the evening there was also an occasion to reflect on trivialization of culture, alluding to Vargas Llosa’s recent book of essays “Civilization of the spectacle”, and to say hello to his old friend Seamus Heaney.

Last weekend The Irish Times featured a laudatory review on The Dream of the Celt published in English by Faber & Faber. The conference transmitted live on twitter is available here: http://storify.com/icdublin/en

Audiolibro de la semana / Audiobook of the week: La buena letra

Parece que hasta el domingo no vamos a ver el sol, así que, ¿por qué no disfrutar del verano irlandés escuchando un buen libro en casa? En realidad, lo puedes oír en cualquier lado con tu MP3, en el autobús, en la bici, o corriendo por el parque cuando salga el sol. Si tu lengua nativa no es el español, también es una buena forma de practicarlo. Y lo mejor de todo es que lo tienes a un solo clic de distancia.

Parece que hasta el domingo no vamos a ver el sol, así que, ¿por qué no disfrutar del verano irlandés escuchando un buen libro en casa? En realidad, lo puedes oír en cualquier lado con tu MP3, en el autobús, en la bici, o corriendo por el parque cuando salga el sol. Si tu lengua nativa no es el español, también es una buena forma de practicarlo. Y lo mejor de todo es que lo tienes a un solo clic de distancia.

La buena letra cuenta la historia de Ana, que a su vez relata a su hijo fragmentos de una vida de pequeñas miserias con las que se han tejido las relaciones personales y familiares. No son grandes acontecimientos históricos los que nos narra su autor, Rafael Chirbes, sino hechos íntimos y cotidianos que suceden en las vidas de unos personajes heridos por la traición y la deslealtad

Rafael Chirbes nació en Tabernes de Valldigna, (Valencia), en 1949. A los 16 años se fue a vivir a Madrid, donde estudió Historia Moderna y Contemporánea. Vivió en Marruecos (donde fue profesor de español), París, Barcelona, La Coruña, Extremadura, y en el año 2000 regresó a Valencia.

Se dedicó a la crítica literaria durante algún tiempo y posteriormente a otras actividades periodísticas. Su primera novela, Mimoun (1988), quedó finalista del Premio Herralde y su obra La larga marcha (1996) fue galardonada en Alemania con el Premio SWR-Bestenliste. Con esta novela inició una trilogía sobre la sociedad española que abarca desde la posguerra hasta la transición, que se completa con La caída de Madrid (2000) y Los viejos amigos (2003). Con Crematorio (2007), un retrato de la especulación inmobiliaria, recibió el Premio Nacional de la Crítica y el V Premio Dulce Chacón. (Datos tomados de Wikipedia.org)

It seems we will not shee the sun until Sunday, so why not enjoy your Irish summer listening a good book at home? In fact, you can hear it anywhere with your MP3, on the bus, bike, or running through the park. If your native language is not Spanish, is also a good way to practice it. And best of all, you have only a click away.

La buena letra is the story of Ana, who tells her son fragments of a life of petty miseries with which they have woven the personal and family relationships. There are not big historical events in this fiction, but intimate and everyday events that happen in the lives of these characters wounded by betrayal and disloyalty.

Rafael Chirbes was born in Tabernes de Valldigna, (Valencia) in 1949. At age 16 he moved to Madrid, where he studied Modern and Contemporary History. He lived in Morocco (where he taught Spanish), Paris, Barcelona, A Coruña, Extremadura, and in 2000 he returned to Valencia. He devoted himself to literary criticism for some time and then to other journalistic activities.

His first novel, Mimoun (1988), was a finalist Herralde Prize and his novel La larga marcha (1996) was awarded in Germany. With this novel, he began a trilogy about Spanish society ranging from postwar to the transition, which is completed by La caída de Madrid (2000) and Viejos amigos (2003). With Crematorio (2007), a portrait of real estate speculation, received the Nacional de la Crítica Award and the 5th Dulce Chacón Award. (Data taken from Wikipedia.org)

Encuentro Literario con Mario Vargas Llosa / Literary evening with Mario Vargas Llosa

Premio Nobel de Literatura en 2010, Premio Cervantes en 1994, Premio Príncipe de Asturias de las Letras en 1986… éstos son tres ejemplos de los muchos reconocimientos que ha recibido a lo largo de su carrera como escritor Mario Vargas Llosa, uno de los más importantes novelistas y ensayistas contemporáneos. El Instituto Cervantes de Dublín se complace en invitarte a asistir a una conversación entre este magnífico escritor y Juan Cruz.

Premio Nobel de Literatura en 2010, Premio Cervantes en 1994, Premio Príncipe de Asturias de las Letras en 1986… éstos son tres ejemplos de los muchos reconocimientos que ha recibido a lo largo de su carrera como escritor Mario Vargas Llosa, uno de los más importantes novelistas y ensayistas contemporáneos. El Instituto Cervantes de Dublín se complace en invitarte a asistir a una conversación entre este magnífico escritor y Juan Cruz.

Mario Vargas Llosa, nuestro autor del mes de junio, nació en 1936 en Arequipa (Perú). En 1959 viajó a España gracias a una beca para hacer un doctorado en la Universidad Complutense de Madrid, donde obtuvo el título de Doctor en Filosofía y Letras.

Ese mismo año, vio la luz su primera publicación, Los jefes, un conjunto de cuentos que obtienen el Premio Leopoldo Alas. Sin embargo, no será hasta la década de 1960 cuando publique tres de las obras que lo lanzaron a la fama: La ciudad y los perros (1962), La casa verde (1965) y Conversación en La Catedral (1969).

En 2010, la editorial Alfaguara publica El sueño del celta, en la que se cuenta la peripecia vital de un hombre de leyenda: el irlandés Roger Casement, uno de los primeros europeos en denunciar los horrores del colonialismo. Esta novela, traducida al inglés, ha sido publicada por la editorial Faber and Faber a principios de junio de 2012 bajo el título The dream of the celt.

Mario Vargas Llosa conversará con Juan Cruz, periodista y escritor español que en la actualidad ocupa el cargo de adjunto a la dirección del diario El País. Su primera novela fue publicada en 1972 bajo el título Crónica de la nada hecha pedazos. Ha participado en radio y televisión y también en numerosas conferencias y cursos.

Para asistir a este encuentro es necesario presentar invitación. Para conseguirla, pregunta por favor al bibliotecario: bibdub@cervantes.es. ¡Pero date prisa, que se acaban!

Nobel Prize in Literature 2010, Cervantes Award 1994, Príncipe de Asturias de las Letras Award 1986… three examples of the many awards that Mario Vargas Llosa has received during his writing career. He is one of the most significant contemporary novelists and essayists. Instituto Cervantes Dublin is proud to invite you to a conversation with this outstanding author and the Spanish writer Juan Cruz.

Mario Vargas Llosa, our author of the month in june, was born in 1936 in Arequipa (Peru), travelled to Spain in 1959 thanks to a bursary to complete a doctorate by the Complutense University of Madrid where he was awarded a Doctorate in Philosopy and Literature.

On the same year, he published his first work, Los jefes (The leaders), a compilation of stories. He was awarded the Leopoldo Alas prize for this piece. It is not, however, until the 60´s when he published three of the works that launched him to fame: La ciudad y los Perros (The City and the Dogs) in 1962, La casa verde (The Green House) in 1965 and Conversación en La Catedral (Conversation in the Cathedral) in 1969.

Following a period of intense political activity, he returned to writing in 1993 with his book of memoirs El pez en el agua (A Fish in the Water).

Alfaguara publishing house launched El sueño del celta in 2010. This is Vargas Llosa’s latest novel where he tells the life story of a legendary man: the Irish Roger Casement, one of the first Europeans to denounce the horrors of colonialism. This novel has been translated into English and is due to be published by Faber and Faber at the beginning of June 2012 with the title The dream of the Celt.

Juan Cruz, Spanish journalist and writer, is Assistant Director at the Spanish newspaper El País. His first novel was published in 1972 with the title Crónica de la nada hecha pedazos. He has participated in radio, television and in numerous conferences and courses.

Please remember: Strictly by invitation. Ask the librarian for details: bibdub@cervantes.es

Entrevista con Miguel Aguilar

Miguel Aguilar: Las editoriales pequeñas, muchas veces, ejercen de cantera de las editoriales más grandes

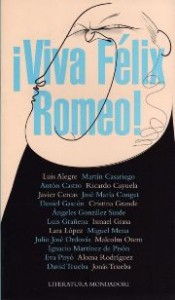

Entrevista con Miguel Aguilar realizada el 29 de mayo de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en el “Homenaje a Félix Romeo” junto a Luis Alegre, Malcolm Otero Barral, Ignacio Martínez de Pisón y David Trueba.

Miguel Aguilar (Madrid, 1976) es, desde el año 2006, director literario de la editorial Debate. Con anterioridad, ha sido editor de no ficción en Tusquets y editor en Random House Mondadori. Como traductor, ha publicado una antología del escritor británico Cyril Connolly, Obra selecta (Lumen, Barcelona, 2005), y otra de George Orwell, Orwell periodista (Global Rhythm Press, Barcelona 2006).

Sergio Angulo: —Miguel, me gustaría que nos explicases en qué consiste el trabajo de un editor.

Miguel Aguilar: —El trabajo de un editor tiene dos partes, creo yo. En una haces de filtro de todas las propuestas de libros, de todas las novelas, los ensayos, de todos los autores que hay en circulación y que se aproximan a ti o que te llegan a través de agentes. Tienes que seleccionar aquellos que te parecen más interesantes. Esa es solo la primera mitad. En la segunda mitad, haces de altavoz de aquello que has seleccionado, que has filtrado. Intentas difundirlo a la mayor cantidad de gente posible, intentas darle la mejor portada, la mejor edición, la mejor promoción en prensa, presentarlo de la mejor manera posible a los libreros. En definitiva, intentas proyectar a los lectores, que al final son quienes van a decidir si el libro les gusta o no, aquello que tú has seleccionado.

Sergio Angulo: —En una editorial, ¿qué tipo de trabajos hay? Traductores, correctores, editores…

Miguel Aguilar: —Bueno, hay muchas partes del engranaje que están externalizadas. Por ejemplo, traductores y correctores suelen estar fuera de la estructura. Los departamentos más importantes son el de Edición, que se encarga de la selección de los títulos y de supervisar todo el proceso. Está el Departamento de Derechos, que es muy importante porque se encarga de todo lo que es la contratación de los libros que vas a publicar, y en muchos casos también de la venta de derechos de traducción a otras editoriales de otros países de esas novelas, y también de cesiones a colecciones de quiosco, o colecciones de venta a plazos, o de clubs del libro…

Tienes el Departamento de Redacción, que es el que supervisa la maquetación de los libros, la corrección de los textos etc., para que no haya erratas, para que todo esté bien compuesto y bien maquetado. Está el Departamento de Diseño, que se encarga de la parte gráfica, de las portadas, las ilustraciones si las hubiera, etc. Y luego tienes el Departamento de Producción, que es la parte, digamos, más industrial, la que tiene que ver con el papel y la tinta, con las imprentas, con que los libros entren, sean fabricados. Y luego tienes la parte comercial y de marketing, que se encarga más directamente de la comercialización. El Departamento de Marketing tiene la función de estimular al librero, sobre todo, a que pida ejemplares de los libros y esté un poco encima de ellos. Comercial son los señores que van a las librerías y consiguen que el librero pida cinco ejemplares de este libro, o veinte del siguiente. Por último, está Prensa, que como su propio nombre indica, son los que hablan con los periodistas, intentan lograr el mayor eco posible de la publicación.

Sergio Angulo: —¿En cuánto valorarías el impacto que pueda tener un buen editor sobre la obra final de un autor?

Miguel Aguilar: —La calidad de la obra final es responsabilidad básicamente del autor. Hay relaciones muy famosas. Quizá Maxwell Perkins sea el ejemplo más claro, un editor mítico estadounidense que era el editor de Scott Fitzgerald. De hecho, el Premio de la Asociación de Editores Americanos se llama Premio Maxwell Perkins. Son editores que realmente entran mucho en el texto y son capaces de convencer al autor de cambiar cosas. Pero yo creo que lo que más puede aportar un editor, más que a la calidad en sí de la obra, es al eco que puede tener, a la difusión. Ahí yo creo que sí, que un editor puede ser capaz de hacer que un buen escritor llegue a un público muchísimo más amplio.

Hay un símil un poco cruel pero que sí que encierra algo de verdad, que es que las editoriales pequeñas, muchas veces, ejercen de cantera de las editoriales más grandes. Y eso es así porque una editorial más grande, por los recursos que tiene a su disposición, porque puede invertir más en marketing, porque tiene una red comercial más desarrollada, puede ser capaz de que un escritor con una obra interesante llegue a un público muchísimo más amplio. Porcentajes, no me atrevería a decirte, pero sí que puede ser bastante importante.

Sergio Angulo: —Ahora que has hablado de editoriales grandes, ¿qué te parecen estos premios literarios que ofrecen a veces las editoriales más grandes? Mueven un montón de dinero y tienen una difusión enorme, pero últimamente tienen mala reputación porque se entregan los premios antes de que falle el jurado…

Miguel Aguilar: —Pues mira, me hace gracia lo de «últimamente» porque hace poco, Malcolm Otero, que estaba en esta silla hace un rato, recordaba que se celebraban los 49 años (no sé por qué no esperaron a los 50) de las conversaciones de Formentor, que eran unas conversaciones poéticas y literarias que se celebraban en el Hotel Formentor, en Mallorca, y que tuvieron cierta continuidad y dieron pie al Premio Formentor y al Premio Internacional de la Edición, que fueron premios muy importantes a nivel internacional a finales de los 50 y principios de los 60. Y entre varias otras cosas, había una entrevista a Carlos Barral, abuelo de Malcolm. Yo creo que debía ser el año 63 o 64, y en ella ya arremetía contra los premios literarios como una vergonzosa plataforma de marketing y de ventas. Con lo cual, la mala reputación de estos premios no es reciente, es de hace mucho tiempo.

Creo que hay que distinguir entre los premios que son a obra publicada: el Premio Nacional de Ensayo, Premio Nacional de Literatura, el Premio Salambó, por ejemplo, que se concede en Barcelona… y los premios a obra sin publicar, que es un poco una peculiaridad de España. Otros países no tienen este tipo de premios. Los premios que se dan a obras sin publicar, hay que considerarlos más bien como una plataforma de lanzamiento, más que como un reconocimiento de una calidad intrínseca. Y como tal, yo creo que sirven para llamar la atención de los lectores sobre una obra determinada. ¿Es criticable? Pues hombre, yo personalmente creo que no. Siendo parte de la industria, me cuesta entender que sea problemático eso. Tampoco me parece que sea un engaño a los lectores. Los lectores saben lo que hay detrás del Premio Planeta, o detrás del Premio Torrevieja, etc. No creo que nadie pueda sorprenderse de que, año tras año, los ganadores sean gente muy conocida y con muchas perspectivas de venta. En ese sentido, me parece que lo que hay que saber es que, en cuanto a reconocimiento de la calidad literaria, no son las mejores guías y, sin embargo, sí que hay otros premios que aportan eso.

Sergio Angulo: —En tu faceta como traductor, has traducido ensayos de un autor que a mí me gusta mucho, George Orwell. En George Orwell, a veces es difícil ver esa línea entre lo que es ficción y lo que es periodismo. ¿Está ese tipo de periodismo volviendo a ponerse de moda?

Miguel Aguilar: —Es curioso porque en Orwell, en principio, (Kapuscinski es otro caso semejante) parece que todo es de una fidelidad absoluta a los hechos y a lo que ha ocurrido. Y luego, si empiezas a escarbar, siempre, inevitablemente, encuentras que hay algún detalle que ha limado. Tanto en Homenaje a Cataluña como en Sin blanca en París y Londres.Son dos libros que, si bien parecen testimonios totalmente reales de lo que ocurrió, los biógrafos de Orwell han ido encontrando pequeñas inexactitudes y pequeños detalles que no terminan de encajar del todo.

Pienso que es un periodismo que no necesariamente es que esté volviendo, es que nunca desapareció del todo, y quizá lo que sí que está volviendo es una necesidad de la gente de tener relatos de la realidad más verídicos. Yo creo que el ensayo ha pasado por una temporada bastante dura, poco atractiva para los lectores, y ese tipo de ensayo sí está volviendo ahora. Sospecho que tiene que ver con la crisis económica, con la situación de preocupación generalizada por el mundo en el que estamos y hacia el que nos dirigimos. Necesitamos voces que nos cuenten qué es lo que está pasando, y eso es algo que Orwell hizo muy bien en los años 30, que Kapuscinski, en sus maravillosas crónicas de América Latina de los 70, por ejemplo, o sus crónicas sobre África y la Unión Soviética, hizo muy bien también… Me parece que está volviendo a haber un público más amplio. No sé si es tanto porque antes no se hacía, o porque ahora sí que tiene más audiencia ese tipo de periodismo.

Sergio Angulo: —Con Internet, que hace que las noticias se actualicen cada minuto, a lo mejor ese tipo de periodismo tiene ahora más lugar en la prensa escrita y las noticias pasan a un lugar digital.

Miguel Aguilar: —Sí, yo creo que sin duda eso es una consecuencia lógica de lo que dices. Es imposible que un periódico dé una noticia, porque todo el mundo la conoce ya. Incluso, en muchas ocasiones, si consultas Internet por la noche, te despiertas a la mañana siguiente, lees el periódico y te da la sensación de que ya lo has leído todo. Y efectivamente, son esas crónicas, o esos artículos de opinión, los que deberían aparecer en los periódicos en papel, para aportar ese valor y ese carácter diferencial. Porque si no, no pueden competir. Es imposible competir contra un medio que tiene la inmediatez de la radio, más el carácter visual de la televisión. En fin, lo tiene absolutamente todo, y lo único que puedes hacer es aportar ese tipo de voces y de experiencias que en Internet se pierden por el maremágnum.

Sergio Angulo: —¿Y crees que llegará el momento en que habrá una diferencia total entre la prensa escrita, tirando hacia la literatura o hacia ese tipo de periodismo, y la digital, dedicada solo a las noticias?

Miguel Aguilar: —Creo que es posible que se especialicen, que aparezcan fenómenos en papel más cuidados, más seleccionados quizá. Pero lo que me cuesta ver es que nada que haya en papel no exista también en Internet. Por ejemplo, hay una revista que no sé si circula también por el Cervantes de Dublín que se llama Jot Down, que es una revista cultural española que tiene articulistas muy buenos. Ahí firma gente como Azúa, como Savater, como Enric González, como Manuel Jabois… Hasta ahora era solo digital, pero va a sacar un número en papel con lo mejor que ha aparecido en digital. Va a ser un número bastante amplio, como cuatrocientas páginas, y se va a vender como un libro. Yo sí veo ese tipo de edición para coleccionistas en papel de aquello que ha salido en digital. Pero por la propia facilidad de la tecnología, me cuesta ver que haya cosas en papel que no aparezcan también en digital.

Sergio Angulo: —Sobre tu faceta de traductor otra vez. ¿Cómo lidia un traductor con los aspectos culturales implícitos en el texto? ¿Tiene a veces que hacer una investigación?

Miguel Aguilar: —Sí, es conveniente. También estás traduciendo para el lector de tu propia época, con lo cual, muchas veces, es mejor tirar de notas al pie, intentar dar un poco el contexto más que reflejarlo en la propia traducción. En el caso de Connolly, que es probablemente el libro que más me ha gustado traducir, es una antología de casi 900 páginas con artículos sobre todo tipo de temas culturales y un marco referencial amplísimo porque era un licenciado en Clásicas en Oxford, con lo cual, las referencias clásicas, por ejemplo, eran frecuentísimas. Y probablemente, para el público al que él escribía esas crónicas, que era un público culto de los años 30 y 40, eran más familiares, pero para un lector español del 2005, que es cuando salió el libro, eran totalmente remotas e incomprensibles. Entonces yo creo que hay que intentar acompañar un poco al lector, darle un poco de apoyo, pero tampoco atosigarle con ese contexto cultural. Hay que dejar también que se defienda un poco, que si hay cosas que le interesan, pueda investigar. Además, antiguamente la Espasa solo la tenía cierta gente, pero ahora, entrar en Google es bastante sencillo y relativamente fiable.

Sergio Angulo: —Para un joven escritor que está empezando a escribir y quiere empezar a publicar, ¿qué le aconsejarías como editor? ¿Dirigirse a una pequeña editorial? ¿Empezar con premios?

Miguel Aguilar: —Bueno, hay muchos premios regionales y de ayuntamientos que están muy bien y que no suponen la plataforma de promoción de las que hablábamos antes, pero que siempre son un camino, y desde luego, todo lo que sea aproximarse a editoriales grandes o pequeñas está bien. Trabar contacto con ellas, poder colaborar como lectores o como correctores, o lo que sea, y ver un poco cómo es ese mundo, que no es particularmente hostil. Al revés, yo creo que es bastante acogedor. No sé si todo el mundo opina igual, pero es mi opinión. Eso siempre da un poco de confianza y de facilidad a la hora de presentar un manuscrito.

Enlaces recomendados

- [Vídeo] Entrevista realizada a Miguel Aguilar en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín por Sergio Angulo.

- Miguel Aguilar en …Sigueleyendo: Textos breves para consumir en red, El Proust, La maleta

- Miguel Aguilar en Twitter.

Interview with Miguel Aguilar

Miguel Aguilar: Small Publishing Houses Often Act as a Source for Larger Publishers

Interview with Miguel Aguilar held on 29th May 2012 at the Dámaso Alonso Library of the Instituto Cervantes Dublin in connection with his participation in the “Tribute to Félix Romeo”, with Luis Alegre, Malcolm Otero Barral, Ignacio Martínez de Pisón and David Trueba.

Miguel Aguilar (Madrid, 1976) has held the position of Director of the Debate Publishing Company since 2006. He has previously been editor at Random House Mondadori and of non-fiction works at Tusquets. As a translator, he has published an anthology of Cyril Connolly, Selected Works (Lumen, Barcelona, 2005), and George Orwell, Orwell journalist (Global Rhythm Press, Barcelona 2006).

Sergio Angulo: —Miguel, I’d like you to explain to us what the work of an editor entails.

Miguel Aguilar: —The work of an editor has two parts. On the one hand, you act as a filter for all the different book proposals, novels, essays, for the different authors who are in circulation and approach you directly or come through agents. You have to select those that seem most interesting. That’s just the first half. On the second hand, you act as a spokesperson for what you have selected, what you have filtered. You try to spread it to as many people as possible, try to create the best cover, edit it well, give the best press coverage and present it in the best possible light to booksellers. In short, you try to reach the readers, who are ultimately the ones who will decide if they like the book or not – the things that you’ve selected.

Sergio Angulo: —What kind of jobs are in a publishing house? Translators, proofreaders, editors…

Miguel Aguilar: —Well, there are many tasks that are outsourced. For example, translators and editors are often freelance. The most important section is the Managing Editorial Department, which is responsible for the selection of titles and overseeing the whole process. There’s also the Contracts and Legal Department, which is very important because it’s responsible for all the legal paperwork of the books that are being published and also, in many cases, for the sale of the translation rights to other publishers in other countries, the transfer of collections to newstands, hire-purchase contracts or book clubs…

You have the Editorial Department which oversees the layout of books and the editing of texts to avoid misprints, so that everything is well written and well formatted. The Creative Department is responsible for the graphics, the covers, the illustrations etc. Then you have the Production Department, which is more industrial and has to do with paper and ink, with printing, with the production and making of books. The Sales and Marketing Department is directly in charge of marketing. Marketing has a role in encouraging the booksellers, especially, to sell them copies of the books and stay on top of things. The Sales Department are the people who go to bookstores and get the bookseller to buy five copies of this book, or twenty of the next. Finally, there’s the Press Department, which, as its name suggests, deals with the media in order to achieve as much publicity as possible for publications.

Sergio Angulo: —What’s the impact of a good editor on the final work of an author?

Miguel Aguilar: —The quality of the final work is basically the author’s responsibility. There are very famous relationships. Maxwell Perkins may be the finest example. He was an American editor who was the editor of F. Scott Fitzgerald. In fact, the prize of the Association of American Publishers is named the Maxwell Perkins Award. They are editors who become really involved with the text and are able to convince the author to change things. But I think an editor contributes mostly, not to the quality of the work itself, but to the impact it can have. I think an editor is able to ensure that a good writer reaches a much wider audience.

There is a simile which is a bit cruel but it does contain some truth, which is that small publishing houses often act as a source for larger publishers. This is because a larger publisher has more resources at its disposal, can invest more in marketing, and because it has a more developed commercial network, it is able to ensure that a writer with interesting work reaches a much wider audience. I wouldn’t dare tell you about percentages, but they can be quite significant.

Sergio Angulo: —Now that you’ve mentioned big publishers, what do you think of these literary prizes sometimes offered by the larger publishers? They involve a lot of money and have a vast reach, but lately they’ve gotten a bad reputation because the winners are known before the jury has made its decision…

Miguel Aguilar: —Well, I think it’s funny to say “lately” as not long ago, Malcolm Otero, who was sitting in this chair, remembered that the 49th anniversary of the Formentor Talks was commemorated (I’m not sure why they didn’t wait to celebrate the 50th anniversary). They were poetic and literary talks that were held at the Hotel Formentor in Mallorca and continued on from there, giving rise to the Formentor Award and the International Editing Award, which were major international awards in the late ’50s and early ’60s. And amongst other things, there was an interview with Carlos Barral, Malcolm’s grandfather. I think it was around 1963 or 1964, when he criticized literary prizes as a shameful platform for marketing and sales. So you can see, the bad reputation surrounding the awards is not recent, it goes way back.

I think you have to distinguish between awards that are given to books that have already been published: the National Essay Prize, the National Book Award, the Salambó Award, for example, awarded in Barcelona… and awards for unpublished work, which is a bit of a peculiarity in Spain. Other countries have no such awards. The awards given to unpublished works are to be regarded as a launching pad, rather than a recognition of an intrinsic quality. In this way, I think they suceed in drawing the attention of readers to a particular work. Is it something questionable? Well, I don’t think it is. Being part of the industry, I don’t find it problematic. Nor do I think it is misleading to readers. Readers know what is behind the Planeta Award or behind the Torrevieja Award, etc. I don’t think anyone can be surprised that, year after year, the winners are well known writers with many sales prospects. In that sense, I think that what you need to know is that, in terms of literary quality, they are not the best guides and yet, there are other awards that provide that.

Sergio Angulo: —In your role as a translator, you have translated essays of an author that I like a lot, George Orwell. In George Orwell, it is sometimes difficult to see the line between what is fiction and what is journalism. Is this kind of journalism coming back into fashion?

Miguel Aguilar: —It’s funny because in Orwell, in principle, (Kapuscinski is a similar case) it seems that everything is an absolutely faithful to the facts and to what happened. But then, if you start digging, you always, inevitably, find that there is something that has been polished. It happens both in Homage to Catalonia and Down and Out in Paris and London. These are two books that even though they seem completely real testimonies of what happened, Orwell’s biographers have found small inaccuracies and small details that do not quite fit.

I think it’s a kind of journalism that’s not necessarily coming back. It never disappeared completely. Perhaps, what is coming back is people’s need to have stories of true reality. I think the essay has gone through a pretty tough time, as it was unattractive to readers, but this kind of essay is certainly coming back. I suspect it has to do with the economic crisis, the situation of general concern about the world in which we are living and where we are headed. We need voices that tell us what is going on, and that’s something that Orwell did very well in the ’30s. Kapuscinski did well too in his wonderful chronicles of Latin America of the ’70s, for example, or in his book on Africa and the Soviet Union. I think it’s gaining a wider audience again. I don’t know if it’s because it wasn’t done before or because now there is an audience for that kind of journalism.

Sergio Angulo: —With the Internet, the news is updated every minute. Maybe this kind of journalism is more common in the press now and the news has moved to the digital space.

Miguel Aguilar: —Yes, I think that’s definitely a logical conclusion. It’s impossible for a newspaper to break a story, because everybody knows about it already. More and more often, even if you check the Internet at night, you wake up the next morning, read the paper and you get the feeling that you’ve already read everything. And of course, those chronicles or opinion pieces should appear in the newspapers, on paper, to provide that value and distinct character, because if they don’t, they can’t compete. It’s impossible to compete against a media that has the immediacy of radio plus the visual character of television. In a nutshell, it has everything, and all you can do is bring to the Internet the kind of voice and experiences that are lost in thewelter.

Sergio Angulo: —Do you think this will eventually lead to a total separation between the printed press, focussed on literature or that kind of journalism, and the digital press focussed only on the news?

Miguel Aguilar: —I think they might specialise and new paper products will be produced, more selective perhaps. But what I don’t envision is that there are things that exist on paper that don’t appear on the Internet as well. For example, there is a magazine called Jot Down. It’s a Spanish cultural magazine that has very good writers. These include Azúa, Savater, Enric González, and Manuel Jabois… Until now, it was only digital, but they plan to publish a collection of their best digital content. It will be a fairly big issue of around four hundred pages and will be sold as a book. I forsee this type of collector’s edition of digitally published material, but because technology is so easy to work with, it’s difficult for me to comprehend that there are things made of paper that don’t exist in the digital world as well.

Sergio Angulo: —In connection with your role as a translator, how do you deal with the cultural aspects implicit in a text? Do you ever have to do some research?

Miguel Aguilar: —Yes, it is advisable. You’re also translating for the reader of your own time so it’s better to include footnotes and try to give a little context instead of basing it on the translation itself. This was the case with Connolly, which is probably the translation I enjoyed the most. It’s an anthology of nearly 900 pages with articles on all kinds of cultural issues and a huge frame of reference. As he had a degree in Classics from Oxford, the classical references, for example, were numerous. Also, the audience he was writing for in the ’30s and ’40s was probably more familiar, but for a Spanish reader in 2005, when the book came out, the stories were totally remote and incomprehensible. So I think we should try to accompany the readers a little, give them a little support, but not overwhelm them with too much cultural context. We should also give them more freedom to explore things that they find interesting. Before only certain people had the Espasa (Spanish encyclopedia), but now it’s quite simple to use Google and it’s relatively reliable.

Sergio Angulo: —What would you recommend for a young writer who is starting out to write and wants to publish? What would you advise as an editor? Going to a small publishing house? Trying to win prizes?

Miguel Aguilar: —Well, there are many regional and municipal awards that are very good. They are not the promotional routes we were talking about before but they are still an option and whatever way it’s used to approach big or small publishing companies, it’s a good thing. Making contact with them, being able to collaborate as readers or proofreaders, and seeing how that world works a little bit – a world that’s not particularly hostile. On the contrary, I think it’s quite welcoming. I don’t know if everybody has the same opinion but that’s my opinion. That always gives you a little confidence and ease when submitting a manuscript.

Recommended links

- [Video] Interview with Miguel Aguilar by Sergio Angulo at Instituto Cervantes Dublin.

- Miguel Aguilar in …Sigueleyendo: Textos breves para consumir en red, El Proust, La maleta

- Miguel Aguilar on Twitter.

Interview with Ignacio Martínez de Pisón

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: A Writer Seeks to Explain Conflicts

Interview with Ignacio Martínez de Pisón held on 29th May 2012 at the Dámaso Alonso Library of the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin in connection with his participation in the “Tribute to Félix Romeo”, with Miguel Aguilar, Luis Alegre, Malcolm Otero Barral and David Trueba.

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón (Zaragoza, 1960) holds a degree in Italian and Hispanic Studies and has lived in Barcelona since 1982. He writes novels and short stories, as well as screenplays, articles for different newspapers and literary criticism. His novels have been translated into a dozen languages. These include La ternura del dragón (1984), Carreteras secundarias (1996), Enterrar a los muertos (2005; To Bury the Dead, Parthian, 2009), Dientes de leche(2008), and El día de mañana (2011), which won the Premio de la Crítica prize for Spanish fiction 2011 and the City of Barcelona award in 2012. In 2011, he also received the Premio de las Letras Aragonesas prize.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Ignacio, let’s start by remembering Félix’s character. What was he like as a person as a writer?

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: —When I met Félix, he was a boy. He was already a gigantic boy, a boy who knew everything and had read everything. He was about seventeen years old, I think. Even then, he collaborated with newspapers in Zaragoza, as well as magazines, and wrote reviews. I was surprised that a guy so young had read so many books, and so I didn´t trust him. I thought, “This boy can’t have read everything”. But gradually I discovered that he actually had read everything, everything he said and much more. There were many more books he didn’t talk about, that I would later discover he had read. In time, I came to think he had some mental illness, that one guy couldn’t have the head to read so much – so much to know, so much to master, so many fields of knowledge. And he was like that. I really think he had, like Valle-Inclán said, “a privileged skull”.

Carmen Sanjulián: —What do you miss the most about his absence?

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: —I miss the person. Félix was very invasive, in the best sense of the term. He was someone who entered your life, your work, who changed you. He changed you for the better. He intervened in the lives of others to make us as good as we were capable of being. And also, he was a great friend. He was one of those guys you could always trust. Truly, the void someone leaves is felt. The pain Félix’s death left was tremendous. There are many people, many writers, many friends, many intellectuals who felt his death because he was like a reference, the person you could always turn to if you had questions about a title, about a topic, about reading material or a movie. Félix always had answers, answers for everything. His ideas were always very clear. Faced with the usual uncertainties of others, Félix was there and always had a straightforward answer to help you clear your head.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Félix was one of the people you used to give your manuscripts to, and you have admitted that he changed, or helped you to change, the ending of El día de mañana.

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: —His influence was felt in the books of many friends, and certainly in mine. When writing To Bury the Dead, he was one of my regular advisers, who gave me references for my bibliography and provided ideas and points of view. In Dientes de leche, I made use of a story of his, a story about his father, who was a city policeman in Zaragoza, and was obliged to act as an extra in a movie that was filmed there. The mayor forced all the policemen to act as extras in that movie. Félix told me a very nice story about how, many years later, he went with his then-girlfriend, Cristina Grande, and his parents, to see the movie, in which Zaragoza looked like a city in Northern Europe. As they were alone in the cinema, his parents commented aloud on certain things in the movie, “Look, that person is dead”, “that poor creature is sick”, “that guy, we don’t know anything about”, “this one stole some money”. And they kept on making comments about his former colleagues. As Félix was not going to make use of this anecdote in any of his books, I borrowed it for a little story in Dientes de leche.

El día de mañana is a novel I gave to him to read, before handing it over to my editor, and he said to me, “It’s very good, but the ending is superfluous. Those final explanatory pages are not very useful”. So naturally, I reduced it to a minimum. I took out about eight or ten pages because of what he said.

Carmen Sanjulián: —When someone starts reading about Ignacio Martínez de Pisón, one of the first things you read is “Ignacio Martínez de Pisón, writer from Zaragoza, belongs to the new narrative or the new narrators”. Do you feel comfortable with that label?

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: —The new narrative is a phenomenon created in the eighties as a kind of historic fact. It was important to have a different type of literature than the kind written during Francoism. The democracy had to produce new names, new titles and new aesthetics. So the term stuck, and that term took in many of us writers, even though we had little in common. But the truth is, it was good for making us known.

I was lucky because it was a moment in which it was hoped a new generation would appear. So when I took some stories to Anagrama, they immediately said yes because of that need for new writers, writers emerging after Franco’s death. But it was one of those fleeting labels that is useful at a certain moment in time, for making a group of writers known, Then the label disappears. However, many of those writers have remained. Soledad Puértolas, Julio Llamazares, Enrique Vila-Matas and myself, were all with that label. There was a group of writers who continued on, but others ended up disappearing along the way, as often happens in the world of literature.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Family is one of the constant topics in your books, and you speak about family with conflicts. Are there any families without conflicts?

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: —I doubt such a thing exists. Not even the concept seems imaginable. I get the feeling that family is the sphere in which conflicts multiply or amplify, and therefore, it´s the ideal sphere for a writer, because a writer strives to discuss conflict.

Carmen Sanjulián: —So the idea about happy families…?

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: No, Tolstoy already covered that.

Carmen Sanjulián: —You have been writing and publishing for over 25 years. The topics are endless.

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: —It’s been a long time – my first book came out in 1984. It’s been almost 28 years since my career as a writer began. It’s true that, even though you never know what your next book is going to be, the ideas come to you. There are many things that have to be told, that expect to be told, and the only thing you have to do is be alert, be vigilant the moment an idea crosses your path and offers itself to you. Even now, I don’t know what my next novel will be, the one after the novel I’m writing now – what it´s about or how it will turn out ?.Nevertheless, I’m sure when I finish the novel I’m writing, an idea will come to me immediately.

Carmen Sanjulián: —How have you evolved from when you started up to now?

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: —When I started, discussing realism was like speaking about transient literature, literature from the past, fluffy literature, and no writer from the eighties wanted to be a realist writer. In time, I came to realize that I actually was a realist writer. I had a tendency to write stories well rooted in reality, close to my life, close to the places I live or have lived, and more and more, my books started resembling me and my own life. So the biggest change in my biography as a writer is that my literature began strongly resembling the realist tradition.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Have you experienced the same evolution as a reader?

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: I’m much more open as a reader. There are many kinds of books I like, that I would never be able to write or even attempt. I find the aesthetics of many writers, that differ from mine, interesting too. Although it´s something alien to me, it´s also quite interesting. In spite of everything, it’s true that you always seek to nourish yourself with the voices closest to you. Maybe that’s why, in the past ten or fifteen years, I´ve mostly read North-American literature, which probably has the most powerful realist tradition.

Carmen Sanjulián: —What does Zaragoza mean to you?

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: —Zaragoza is the city where I was born, where I spent my formative years as a person, and therefore, it’s the most important city of my life, even though it’s not necessarily the city I’ve spent most of my time in. In fact, I’ve been living in Barcelona for many more years. But it’s inevitable for my characters to go back to Zaragoza. I constantly return to Zaragoza through my books and through my characters.

Carmen Sanjulián: —There are some writers who say they refuse awards. Is that only act? Deep down, does everybody like to get recognition in the form of awards?

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: —Well, you always like it. You always like when you get told that someone liked one of your books. If it’s one of those awards where you don’t present yourself but you get a phone call and they tell you, “Look, we decided to give out this award or that one. We have come together, and we decided your book is the one we liked the best in the past few months, or the past year”. It’s one of those things that helps you to keep going. There’s another reason to keep on writing.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Javier Barreiro was here a few months ago and he said Aragón is particularly tough on its sons. But not in your case.

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: —No. I don’t think it’s like that. I think Aragón has been very kind to its artists. The fact that some of them had to leave in order to develop their careers away from Aragón is part of the logic. I mean, the fact that the best filmmakers from Aragón have made their careers outside of Aragón is logical, because there is no film industry in Aragón. I think there are very good writers from Aragón who still live there, and there are some who live away, but I don’t think there is any reason to think Aragón is that bad. No. On the contrary, I feel very well treated and very loved in Aragón, and indeed, very rewarded by the awards I’ve received there.

Recommended links

- [Video] Interview with Ignacio Martínez de Pisón at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin by Carmen Sanjulián.

- [Video] Interview with Ignacio Martínez de Pisón on Cervantes TV.

- Reviews of El día de mañana, Dientes de leche and Enterrar a los muertos in El Cultural.

About Félix Romeo

- Félix Romeo in Letras Libres.

- [Audio] Adiós a Félix Romeo on Radio 3.

< List of interviews

Interview with Luis Alegre and David Trueba

Luis Alegre and David Trueba: Ireland Proves that the Great Legacy of a Country is its Culture

Interview with Luis Alegre and David Trueba held on the 29th May 2012 at the Dámaso Alonso Library of the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin in association with their participation in the “Tribute to Félix Romeo”, with Miguel Aguilar, Malcolm Otero Barral and Ignacio Martínez de Pisón, and the film screening Fernando’s Chair.

Luis Alegre (Lechago, Teruel, 1962) is a versatile writer, journalist, film maker and television presenter. Since the ’80s, he has worked with different types of media. As an essayist, he has published Besos robados. Pasiones de cine (1994), El apartamento; Belle Époque (1997), Vicente Aranda: la vida con encuadre (2002), Maribel Verdú: la novia soñada (2003); and as an editor, Diálogos de Salamina: un paseo por el cine y la literatura (2003), among others works. In 2006 he directed the documentary film La silla de Fernando, a conversation with Fernando Fernán Gómez, with David Trueba, which was nominated in 2007 for Best Documentary Film at the Goya Awards.

David Trueba (Madrid, 1969) is a writer, journalist, screenwriter and film director. He started out as a screenwriter with Amo tu cama rica (1991) and Los peores años de nuestra vida (1994), he directed his first film, La buena vida, in 1996, followed by Obra maestra (2000), Soldados de Salamina (2002), the film adaptation of the novel by Javier Cercas, Bienvenido a casa (2005), La silla de Fernando (2006) with Luis Alegre, Madrid 1987 (2011), and Vivir es fácil con los ojos cerrados (2013). As a novelist, he has published Abierto toda la noche (1995), Cuatro amigos (1999) and Saber perder (2008), winner of the National Critics Award that same year. His novels have been translated into more than fifteen languages.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Let’s start with the tribute to Félix Romeo. When a friend passes away, he obviously leaves an emptiness that is extremely difficult or impossible to fill. I would like you to tell me what kind of hole Félix has left in your life?

Luis Alegre: —Félix left an enormous hole, immense, but even more so, because it was a traumatic loss, it was totally unexpected, I think we haven’t wrapped our minds around the idea that he’s gone. When someone who’s eighty-something years old, who you love very much, passes away, you perceive it as a normal part of life, and you accept it in a way. But in the case of Félix Romeo it has been a kind of nightmare for all of us who loved him. And also, I think it’s a very significant loss for Spanish culture because he was one of the most original, freest, overwhelming personalities that existed.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Yesterday you mentioned that one of Felix’s vindications was love, that you had to vindicate love and that he had the mantra “¡viva el amor!”. Do you carry on that legacy of vindicating love?

David Trueba: —Especially Luis.

Luis Alegre: —It’s very easy to share that vindication, but the thing is that Félix did it so vehemently, with such passion, such constancy and such joy that it was really impressive. He loved love very much, loved joy, loved life, loved freedom, loved beauty, culture, loved the best things in this world, the best things in people, as we all love them, but he did it with his own personality and with his style, that was very peculiar and very attractive and very funny as well.

David Trueba: —Yes, I think there is a misunderstanding in a certain part of society about culture, art, in the sense that it has to be something boring, tiresome, that provokes a certain seriousness, a certain solemnity in people who approach it from the outside, or in those who create it. But we always shared the same vision about that, which was that we dedicated ourselves to these things because they brought us enormous pleasure, they brought us enormous joy. We thought the best thing we could offer and dedicate to society, was our work, our inventions, our films, our books, our passion for something we read or heard or discovered in an exhibition. We never understood the association of culture with the tiresome, the boring, with complaints.

He represented exactly that, a calling for joy, for pleasure – to give that pleasure to others and not have any complex regarding other professions or dedications, which may have more emotional stability, more work stability, but in spite of that, they certainly can’t provide the moments of happiness that we experienced. In this way, he was truly and absolutely a militant and an apostle of joy, of happiness, of the need to love each other, caring, preaching it and at the same time, streesing the need to do our job as a manifestation of that joy. In this way, I think we are still faithful to it, it won’t be easy to take it away from us.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Let’s move on to another friend, to Fernando Fernán Gómez. You both directed La silla de Fernando, a film that was made in several months.

Luis Alegre: —Those who know a little about Spanish culture know that Fernando Fernán Gómez was one of the key personalities of Spanish cultural history of the 20th Century from many different points of view – as an actor (his most popular facet) but also as a film director, writer, theatre director, stage actor, as a memoir writer, as a television producer and scriptwriter and TV actor. Ultimately, he is one of the most multi-faceted personalities who has contributed to a significant part of the arts of the 20th Century. He’s a kind of synthesis of everything.

In each one of those genres he has created key works: in film, in theatre, television and literature. We are among the many admirers he has, those who recognize the importance of Fernando Fernán Gómez in terms of Spanish culture. But there was something that especially seduced David and myself, as it did for many of his friends. It was his wonderful way of seeing life and his incredible way of explaining it. We could see he had a gift for communicating the ways in which he experienced life and the things that happened to him. We thought his art could only be enjoyed by those of us who knew him and enjoyed his friendship. We got the idea of making a film to try and convey our fascination to everybody who watched it. We wanted to communicate the very unique art of speaking, of sharing things about life, and to acknowledge a way, which for us is almost revolutionary, of understanding the world and life itself.

David Trueba: —Yes, it’s a film that has brought us enormous enjoyment. A big box office success wouldn’t have brought us as much satisfaction as this movie. There are several reasons for this. Firstly, we can see the pleasure it evokes in the people who watch it, which is what we were ultimately looking for – to recreate the experience of talking with Fernando, of having a long talk with him across the table, about the divine and the human. Also, because it was a project of ours for a long time, an idea we fantasized about, but there was always some reluctance. We thought, “Well, a film about a man talking, we won’t do that”. At the same time, we thought “We have to do it because we´ll regret not doing it for the rest of our lives when Fernando is gone”. And the satisfaction of now being able to say, “We did it”, was worth it. We didn’t abandon a project, we didn’t leave it only as an idea, we didn’t leave it as something we talked about and never accomplished – we did it. Even better, he came to see it himself and I think it brought him great joy to see it with us that day. That’s how I can tell you, if we counted all our achievements, there are few things we’ve accomplished in life that have brought so much joy.

Carmen Sanjulián: —And it was very well received. I was recently reading a review and the critic gave you nine out of ten and said “nine because it’s short”. Did you have to cut a lot of material? Do you have enough footage for another movie?

Luis Alegre: —We recorded, more or less, twenty hours of conversation with him. No matter how fascinating, we had to keep in mind that it was just a guy talking, so in the end we settled for a duration of eighty-five minutes, which is the average length of a conventional film. Of course, we left out a lot of footage. Some of that footage was included in the extras on the DVD, but we were forced to leave out a lot of footage.

David Trueba: —It was a very hard film to edit because we were very demanding. We had to make sure that it didn´t become boring or tiresome for the viewer. We wanted it to be a movie were people would be left, like the critic said, wanting more. We wanted them to come out saying, “well, I could have watched that for an hour longer”.

The person who gives us an hour and a half of their time, to watch something we make, deserves the best possible treatment. So the editing was very hard. We were asking ourselves for a long time, “Should this piece be cut or not?”, “Let’s think about it, because this goes well here, but this is too long”, etc. So we spent a lot of time polishing it and left out things out about Fernando’s profession because we didn’t want it to dominate the film. So thanks to very careful editing of the DVD, we were able to include two extra hours of footage, for those (and luckily there were many) who watched the hour and a half of La silla de Fernando and thought, “I’d like to hear more of Fernando’s opinions about this or that”. They now have the option of watching it there.

But for us, the film is the way it is and that’s the way it has to be. We always said, when we were presenting it, that it was a very spectacular film for us, because Fernando was a spectacle that was extremely difficult to recreate. Fernando was a juggler of words, of conversation, and also a person who recounts 20th Century Spain in a completely indirect way in this film, and yet it’s as clear, if not more so, than most history books.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Do you have another protagonist you’d like to put in the spotlight?

David Trueba: —That’s extremely difficult because that spot is unique. What we do have, since we had such a good time working together, is a another project, with Luis and myself collaborating again but in a format that exploits all of Luis’s qualities as a collaborator, his skill as a great interviewer, a person with enormous curiosity, who people naturally trust.

Every now and then we think about the idea of getting together again and working with one of those rare characters in Spain, who can not only tell us something interesting about themselves but also shed some light on our world, our country, our culture, the way we are now or our evolution over the last few years. What happens with those projects in the end? Well, the best thing to do is not to mess with them until you actually do it. The one with Fernando Fernán Gómez, for example, was something we never mentioned. It was something we had inside but until you do it, the best thing is not to mention it.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Since we´re in Ireland, a country where many movies have been made, maybe you could even come here?

David Trueba: —Of course, Ireland is a mythical place for us. Not only for the great literature, great music and great cinema it has given us, which has also inpired countless directors in the US. But it also proves something we have been insisting on for a long time in Spain, that the great legacy of a country is its culture, nothing else. It’s not its economy, which is ambivalent as it rises and falls. It’s not, of course, its military prowess, nor its industry, The great legacy of a country, its big personality or large flag, is what it leaves behind culturally.

When you visit Ireland, or Dublin, which has been a pleasure for us, , you discover that the thing the Irish can probably be proudest of is their poets, their writers and the sense of identity they have as a country, much more than other ideas the world of politics or the media try to sell to us.

Carmen Sanjulián: —Speaking of Ireland, a few days ago, I was listening to the radio and heard the question “If anyone had ever been stuck in a bathroom?”. Oddly enough, you can’t imagine how many people called in saying that they had. There were all kinds of anecdotes.

Luis Alegre: —I got stuck in a bathroom once as a child, now that you mention it. Yes, I think we all have in our history a moment in which we have been stuck in a bathroom.

Carmen Sanjulián: —It reminded me, of course, of your movie, Madrid 1987, which has been really successful. Is it based on a real story, did somebody tell you this?

David Trueba: —It’s based on a real anecdote about two people who got stuck in a bathroom, similar to the characters in the film. After that, everything was recreated, invented, the characters are completely fictitious. But it´s curious because in Spain, as well, after the movie, loads of people told me their experiences, not only about getting stuck somewhere, but also about the relationships between two people of very different ages. It’s very interesting how movies urge people to tell you their personal experiences and one of the things I´ve enjoyed most is that the film conveys the experiences of many people. Sometimes people say to you, “that’s impossible”, “that can’t happen”, “that can’t be”, and you say “if I told you the number of stories I’ve been told over the last few months…”

Carmen Sanjulián: —Lastly, I love the beginning of the book Cuatro amigos, about things that are overrated. Should we add anything else to that fantastic list? Should we cross anything off? What do you think?

David Trueba: —Well, I think, unfortunately, there are many overrated things in life. The ones that worry me the most are those that make people’s lives difficult. Because in the end, overvaluing something becomes a part of a person´s way of life. It´s true that you give importance to some things and that’s how it should be, but what worries me is when overvaluing something makes us unhappy, makes life difficult. In that sense, I think the last few years have taught us that money, as much as everybody insisted on it, from the stories we were told, from our parents, etc… well, it´s obviously been proven that money is not the most important thing in life. It´s more important to fill your life with things that make you feel alive.

It´s true that everyday I find more overrated things, as well as things that are undervalued. People don’t realize how important friendship is, how important giving pleasure to others is, how important it is to have a culture, an interior life that allows you to bear the loneliness, that allows you to bear the path of life that typically leads to decline, etc. People pay little attention to all these values in life, and in the end, they are everything.

Recommended links

- [Video] Interview with Luis Alegre and David Trueba at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin by Carmen Sanjulián.

- Luis Alegre’s Blog in El Huffington Post.

- David Trueba in El País.

· About Félix Romeo

- Félix Romeo in Letras Libres.

- [Audio] Adiós a Félix Romeo on Radio 3.

· About Fernando Fernán Gómez

- Fernando Fernán Gómez. Biography in the Instituto Cervantes Libraries.

- Fernando Fernán Gómez. Dossier in El Mundo.

< List of interviews

Entrevista con Ignacio Martínez de Pisón

Ignacio Martínez de Pisón: Lo que busca un escritor es contar conflictos

Entrevista con Ignacio Martínez de Pisón realizada el 29 de mayo de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en el “Homenaje a Félix Romeo” con Miguel Aguilar, Luis Alegre, Malcolm Otero Barral y David Trueba.