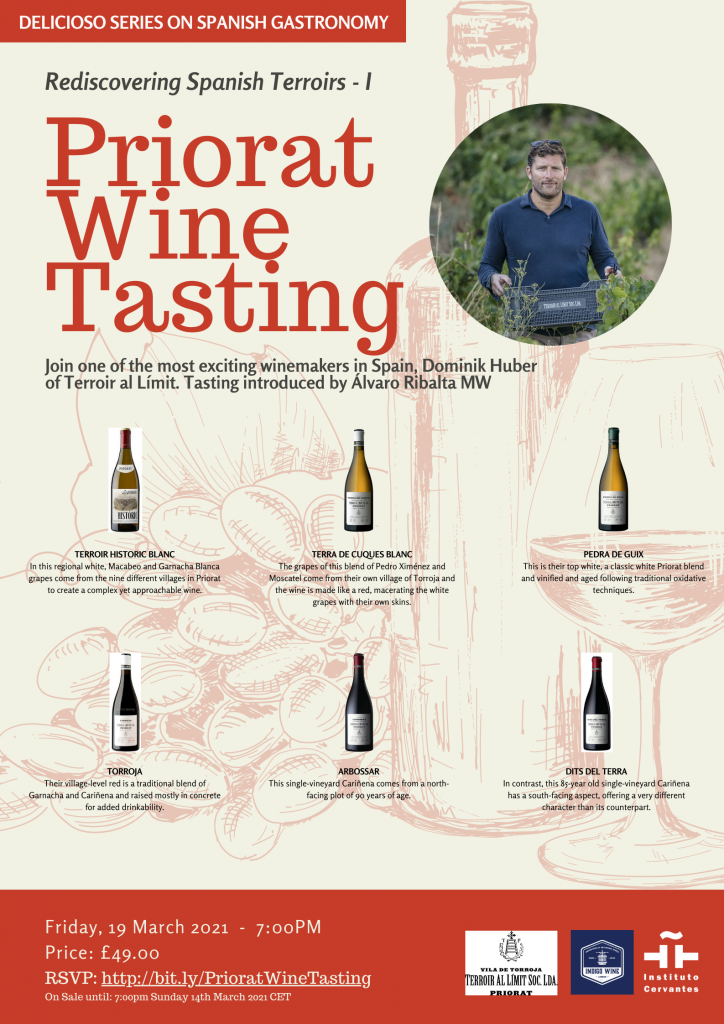

Discovering Priorat: A guided wine tasting

Join us on Friday, March 19th, at 7pm, to discover Priorat through the eyes of one of the most exciting winemakers in Spain: Dominik Huber of Terroir al Limit. Tasting introduced by Álvaro Ribalta MW. Book your ticket by March 14th and you will receive six 50ml tasters to sample at home.

This event will take place via Zoom, will last approximately 2h and will consist of a tasting of six wines and a presentation of Priorat’s different terroirs from the perspective of the founder and winemaker of Terroir al Limit, Dominik Huber.

The following wines will be tasted during this webinar:

Terroir Historic Blanc 2018: In this regional white, Macabeo and Garnacha Blanca grapes come from the nine different villages in Priorat to create a complex yet approachable wine.

Terra de Cuques Blanc 2017: The grapes of this blend of Pedro Ximénez and Moscatel come from their own village of Torroja and the wine is made like a red, macerating the white grapes with their own skins.

Pedra de Guix 2017: This is their top white, a classic white Priorat blend and vinified and aged following traditional oxidative techniques.

Torroja 2017: Their village-level red is a traditional blend of Garnacha and Cariñena and raised mostly in concrete for added drinkability.

Arbossar 2017: This single-vineyard Cariñena comes from a north-facing plot of 90 years of age.

Dits del Terra 2017: In contrast, this 85-year old single-vineyard Cariñena has a south-facing aspect, offering a very different character than its counterpart.

COMUN-ES, la primera comunidad virtual de investigadores del español

COMUN-ES es una herramienta de trabajo diseñada desde la Universidad de Salamanca y la Universidad de Oxford que nace con el objetivo de conectar a los investigadores del español en tres ámbitos clave del hispanismo: Literatura y Estudios Culturales, Lingüística Hispánica y Español LE/L2/LH.

COMUN-ES es la primera comunidad global virtual de la investigación sobre el español. Mediante esta iniciativa de Humanidades Digitales se da respuesta a la necesidad de fomentar la colaboración entre investigadores para crear redes académicas en líneas afines y descubrir nuevas áreas de investigación.

En el siguiente vídeo podrás ver su funcionamiento:

Al registrarte en la plataforma podrás:

– Establecer relaciones profesionales con personas de tus mismas áreas de interés;

– Compartir y difundir resultados de tus labores investigadoras y de tus proyectos;

– Poner en marcha iniciativas conjuntas;

– Colaborar en otras labores académicas (coautorías, comités, tribunales, informes, revisiones de manuscritos, codirecciones de trabajos de investigación, etc.).

Te damos la bienvenida a COMUN-ES y te animamos a registrarte en www.comun-es.com.

Conecta, comparte y colabora. Si investigas sobre el español: únete a COMUN-ES.

«The corona pandemic has isolated most individuals in their private realm»

Manuel Arias Maldonado is Associate Professor in Political Science at the University of Malaga (Spain). Maldonado has been a Fulbright scholar at the University of Berkeley and a visiting researcher in Munich and New York.

Maldonado has published a book in Spain about the sentimentalisation of politics and a number of papers on the digitisation of social life. His latest books deal with the Anthropocene and the Covid-19 pandemic.

Maldonado takes part in this year’s edition of Night of Ideas, at the debate Lonely Together with Fay Bound Alberti, author of A Biography of Loneliness & Cultural Historian, from the University of York, and Clémentine Lalande, CEO of Once online dating app.

This year you take part in the In the Night of Ideas, what does it represent to you?

It is an exciting opportunity to share my thoughs on the topic with the rest of the participants and the public. Tellingly, we will do it thanks to the same technology that will be subject to discussion. On the other hand, the very existence of a Night of Ideas is a tribute to the key role that ideas play in the human experience -as something that invites us to see the world in particular ways and incites us to change it.

The topic of your debate is Lonely Together. What are your thoughts on it?

Human beings have been «lonely together» for centuries. Even before the invention of the print, some cultuvated people wrote to each others letters that crossed continents, thus helping them to alleviate their loneliness or isolation. As new communication technologies emerged, from the telephone to the radio, togetherness could comprise a greater number of people. Yet mass communication did not allow individuals to answer back – we just passively received messages from the few who produced them. Digital technologies are different: individual people can now connect to each other on a regular basis in different ways, ranging from chats to video apps. Thus we can now create our own networks. The public space is thus fragmented, while our private lives acquire a multi-faceted quality. Does this increase loneliness? I am not sure. People still need the direct contact of others and it seems to me that digital technologies just add a new layer of sociality to our everyday lives. For instance, we can be in touch more easily with those who live far from us — be them family or friends. And for those who are shy, writing can be easier than an in-person encounter. Social networks have problems of their own and they must be discussed, but I would argue against the idea that greater connectivity is a bad thing for the individual. Loneliness and togetherness stand in a difficult relation and this relates in turn to the tension between individuality and sociality in human beings. Digital technologies can disrupt such relation, but they cannot put an end to that tension.

How do you feel about the use of digital networks during the current lockdown in the UK and other parts of the world?

The corona pandemic has isolated most individuals in their private realm and this in turn has shown the communicative potential of digital technologies. It may be argued that governments might have never been able to impose such strict lockdowns across the world without the existence of digital networks, which have been very beneficial – they have alleviated loneliness, facilitated the exchange of information, and provided entertainment. In sum, they have been a substitute for ordinary life. Naturally, they have also allowed the continuation of economic activity in many sectors, thus preventing a greater damage to virus-battered societies.

Can we be emotionally connected in the digital world?

Indeed. Emotional connection does not require in-person communication, as the entire history of the novel – not to mention the radio or television – comes to show. There are all kind of experiences in the digital world: some are personally affecting, some are not. On the other hand, it would be necessary to define what do we mean by «emotional connection». To which emotions are we refering to? Social networks can often elicit resentment, animosity or envy (let us think of the effect that the glittering images of the life of others as staged in Instagram usually has on the observers). I am afraid that this should also count as a kind of emotional connection. Yet if we reserve the term for a positive connection, associated to solidarity or love, well, we can feel that connection as well. Needless to say, we may feel that something is missing – that the presence of others provide something to communication that is unique and valuable. But this is no reason to reject the particular type of affective experiencies that digital networks can provide.

«I think what we all miss most is the very heart of what we do: trying to communicate something essential, and sharing a precious connection with an audience»

We interview tenor Nicholas Mulroy ahead of his concert Cubaroque, as part of Baroque at the Edge 2021, that invites leading musicians from all genres to take the music of the Baroque and see where it leads them.

Baroque at the Edge is not able to invite audiences to LSO St Luke’s for the 2021 festival. Instead all events will be available to buy online from now until the January release date, and subsequently available to view until 31 March 2021.

Mulroy was born in Liverpool, and has had a busy and varied career as a singer, where personal highlights have included Bach’s Matthew Passion in his own Thomaskirche, Monteverdi Vespers in Carnegie Hall, and two visits to the fantastic Australian Chamber Orchestra, as well as a broad discography including Handel, Purcell, and Piazzolla’s amazing María de Buenos Aires.

Mulroy combines singing with teaching at Goldsmiths, Cambridge, and the Royal Academy of Music, and directing. He has recently been named Associate Director of Scotland’s Dunedin Consort.

How did you become interested in becoming a tenor?

I sang as a child in Liverpool, and since then have always been involved somehow with music, whether singing or instrumental – when my voice changed I played in local youth orchestras, and had great fun in jazz and rock groups. I also sang salsa and played serenatas during my time in Ecuador, which was a lovely way of getting to know different kinds of music and performance style!

You regularly appear with leading ensembles throughout Europe, which ones do you remember as the most special ones?

I’ve had immense fortune to work with many amazing colleagues, whose inspiration and talent of course I miss at the moment. Every musician, and therefore every ensemble, has their own special energy and qualities, so it’s impossible to highlight some over others. I do, however, have fond memories of favourite concert halls: the Palau in Barcelona with its inimitable architecture; the Chagall ceiling in the Paris Opera; outdoor concerts in the Palacio Carlos V in the Alhambra. We are so fortunate as musicians to be able to work in these spaces, where the fleeting beauty of music can interact, often unforgettably, with architectural wonders.

2020 has been a difficult year to culture with the cancellation of many events and concerts, how has the covid pandemic impact your career?

I think it’s fair to say that we’re all brought low by this pandemic, and not always supported either by governments, though some artistic institutions have been superhuman. There have of course been positives: the chance to refine and reflect, and the emphasis on inner geography is a positive side-effect when it comes to thinking about creativity. On the other hand, apart from the practical implications of having concerts deleted, and income decimated, I think what we all miss most is the very heart of what we do: trying to communicate something essential, and sharing a precious connection with an audience. The fact that so little is feasible at the moment diminishes both musician and listener.

Cubaroque takes place next week. You take a new brand-new exploration from three of this country’s most distinguished baroque musicians. What does it mean to you?

The music of the Baroque has been the central element of my career until now, so singing this repertoire – Monteverdi, Purcell, Marín – is always a little like a homecoming. It’s repertoire of such expression and beauty, and its durability is testament, I think, to the way it still has huge appeal and value now. It’s a challenge and a privilege to try to make the music of the past mean something for people today.

You investigate the cultural and political background of the 1960s Latin-American and Spanish song-writing giants. How do you approach them in Cubaroque?

We wanted to shine some light on these wonderful musicians, and respond to the domination of English-speaking pop music in today’s cultural landscape. Silvio Rodríguez and Víctor Jara are figures of gigantic significance but not well-known outside the Spanish-speaking world. Both carry importance both politically and artistically in a way that is rare anywhere, and shared by only very few: one thinks of Bob Dylan or John Lennon perhaps. The way their creativity interacts with political power is something they share with Purcell and Monteverdi, both of whom were based at institutions of far-reaching influence. In one sense, we’re limited by our instrumental possibilities, so we only play acoustically, and with one voice and two guitars (or similar instruments). We have found, however, that – in spite of the historical and geographical separation – all this music shares many things: sometimes a harmonic progression or a melodic echo, often a similar feeling of confessional intimacy, and always direct, truthful responses to the possibilities that these texts and stories offer.

«El feminismo es una forma de estar en la vida que todo lo impregna»

Entrevistamos a Olga Castro, Profesora Titular de Estudios de Traducción en la Universidad de Warwick. Castro es Licenciada en Periodismo por la Universidad de Santiago de Compostela (USC) y en Traducción e Interpretación por la Universidad de Vigo, se doctoró en 2010 en el Programa Doctoral Traducción & Paratraducción (T&P) con una tesis doctoral que recibió el Premio Extraordinario de Doctorado titulada Tradución, xénero, nación: cara a unha teoría e práctica da tradución feminista.

Actualmente trabajas como Profesora Titular de Estudios de Traducción, ¿cómo es la experiencia de trabajar en la Universidad de Warwick?

Llevo trabajando en la universidad británica desde 2010, cuando emigré desde mi Galicia natal, tras haber concluido mi doctorado en la universidad pública gallega. Antes de llegar a Warwick en 2019 pasé por las Universidad de Exeter y Aston (Birmingham). Cada lugar tiene sus particularidades. En Warwick estoy muy cómoda porque tenemos una Escuela de Lenguas y Culturas Modernas muy potente, con una oferta de programas variada y atractiva. Contamos con la posibilidad de crear asignaturas acordes a nuestros intereses de investigación, lo cual resulta muy motivador. En mi caso, eso ha implicado diseñar la materia «Género y traducción en el ámbito hispánico», en la que estudiamos a poetas y narradoras del Caribe, de Guinea Ecuatorial, de distintos países de Latinoamérica y también de España, inclusive algunas que escriben en lenguas propias distintas del castellano. Además, desde este año coordino también el Máster en Translation and Cultures, una tarea con la que disfruto muchísimo.

Este año fue la cuarta edición de los premios de traducción Warwick Prize for Women in Translation. ¿Qué valoración haces de esta iniciativa?

Es una iniciativa excelente para promocionar la traducción de obras de escritoras al inglés, tras llevar décadas constatando la discriminación y barreras que sufren las autoras extranjeras para acceder al mercado anglófono. De hecho, este premio forma parte de una serie de iniciativas surgidas en los últimos cinco años para tratar de cambiar esta realidad, como queda de manifiesto en el ebook de acceso abierto Translating Women: Activism in Action, que tuve el placer de coeditar, junto a Helen Vassallo, para el Institute of Translators and Interpreters in the UK. Volviendo al premio, el número de obras presentadas ha ido creciendo año a año, aumentando así el número de lenguas originales y territorios representados. Además, en la web del premio se pueden ver todas las obras preseleccionadas y finalistas, de manera que sirve como un catálogo a cualquier persona angloparlante interesada en leer escritoras extranjeras.

Tus principales áreas de investigación incluyen estudios de traducción feminista, ¿por qué te especializaste en este tema?

El feminismo es una forma de estar en la vida que todo lo impregna, y que a grandes rasgos busca erradicar la discriminación y lograr la justicia social para todas las personas del planeta. Trabajar en este tema me permite poner mi grano de arena a avanzar hacia esta justicia, desvelando donde reside la discriminación, analizando alternativas puestas en marcha y proponiendo estrategias que cambien en orden patriarcal establecido. Antes hablaba de las barreras, ya muy estudiadas, que obstaculizan la traducción de autoras de una forma que no afecta a los autores extranjeros; pero existen muchas otras áreas en las que urge actuar: desde la traducción publicitaria o audiovisual con su tendencia a exagerar estereotipos de género, hasta la traducción automática o realizada por personas en las que la/el mediadora lingüística añade sesgos sexistas que no estaban en el original, pasando también por la historia de la traducción, con la invisibilización de aquellas traductoras que reflexionaban sobre su práctica y que, por lo tanto, son también teóricas de traducción.

¿Qué cinco escritoras traducidas a inglés recomendarías y deberíamos seguir de cerca?

Con todas las escritoras relacionadas con el contexto del hispanismo que se están traduciendo en la actualidad, de lenguas y contextos diferentes, resulta difícil elegir. Entre las más recientes que he leído, y que más me ha conmovido, está la ecuatoriana María Fernanda Ampuero, con su libro Pelea de gallos (2018) traducido por The Feminist Press. Dentro de la Península Ibérica, la novela Amaren eskuak de Karmele Jaio es muy potente, y la traducción a inglés está publicada por Parthian. Sara Mesa es otra autora con muy buena acogida en inglés, ya próximamente tendrá cuatro novelas traducidas; entre ellas, me quedo con Cuatro por cuatro, publicada en inglés por Open Letter. Por supuesto, en la lista tiene que estar Melibea Obono, la primera escritora de Guinea Ecuatorial en ser traducida a inglés, con su novela tan combativa La bastarda disponible también en The Feminist Press. Me gustaría cerrar con una gallega, y de entre ellas destaco a Eva Moreda, residente en Escocia, cuya novela A Veiga é como un tempo distinto narra la experiencia de la emigración londinense, y que puede leerse en Francis Boutle. En todos los casos, es imprescindible destacar la extraordinaria labor de mediación cultural y lingüística a cargo de las traductoras y traductores, y desde aquí mi reconocimiento hacia ellas y ellos.

Cortos en femenino

Durante el mes de diciembre, el Instituto Cervantes ofrece el ciclo en línea «Cortos en femenino». Diseñado por la coordinadora de festivales de mujeres en España, Trama, son cuatro ejemplos muy diferentes de la producción de cortometraje actual que muestran personajes femeninos diversos: dos cortos de ficción, «Centrifugado» y «No me despertéis», que rompen las expectativas de cada uno de sus géneros; el corto experimental «Dúctiles», que abre el imaginario sobre la representación de las mujeres; y el corto de montaje «Quand j’étais petit», que se abre hacia el entorno africano.

PROGRAMA

▶ 7 de diciembre: «Dúctiles» (Marisa Benito, 2018)

▶ 14 de diciembre: «Centrifugado» (Mireia Noguera, 2017)

▶ 21 de diciembre: «No me despertéis» (Sara Fantova, 2018)

▶ 28 de diciembre: «Quand j’étais petit» (Elena Molina, 2015)

FIVER CERVANTES. Festival de cine, danza y nuevos medios

FIVER, festival y plataforma internacional de apoyo, exhibición y producción de danza audiovisual creado en España en 2012, presenta en su segundo año de colaboración con el Instituto Cervantes una selección de piezas de realizadores españoles en un programa de cinedanza que podrá verse en abierto en abierto en https://vimeo.com/showcase/fiver del 26 al 31 de octubre.

Comisariado por Samuel Retortillo, director del festival, quiere ofrecer una visión actual de la danza audiovisual a través de cinco obras que han sido producidas por Fiver o que han resultado finalistas en su competición internacional: la ganadora del premio especial FIVER 2019, «Amo a las criadas por irreales», de Sofia Castro (Argentina); la finalista, «Babelian Circles», de Ferrand Romeu, y las obras colaborativas Fiverlabs 2019, «Cuerpo a cuerpo 2.0», coordinada por Esteban Crucci y Jordi Cortes, «Wine or Grape?», coordinada por Álex Pachón; y «Bailaora», de Rubin Stein.

Este programa se amplía con «Cuerpos confinados», una serie de vídeos que han sido realizados durante el confinamiento, con el fin de analizar y dar valor a las propuestas creativas llevadas a cabo durante este periodo, por autores de la talla de Elías Aguirre, Richard Mascherin, Asun Noales, Alex Pachón, Jesús Rubio, Antonio Ruz, Guido Sarli y Pablo Venero.

VII Festival de cine español de Edimburgo: Programa escolar

Vuelve el Festival de Cine Español de Edimburgo e incluye un Programa Escolar dirigido a estudiantes de “Spanish Learning”.

Debido al COVID-19, el formato será en línea y la película estará disponible durante 48 horas, a través de un enlace enviado a los profesores, que les permitiría acceder a ver las películas en clase dentro de un tiempo establecido.

En esta edición, las películas del Programa Escolar son:

- Los Futbolísimos (P7-S2)

- Pakete, Helena y sus compañeros de colegio se meten en todo tipo de aventuras en las que su ingenio y su amistad serán puestos a prueba. Todo para descubrir el misterio que podría acabar con su equipo de fútbol y con la continuidad de la pandilla. ¿Son víctimas de una conspiración o es todo fruto de la casualidad? Ha llegado el momento de hacer un pacto secreto y crear Los Futbolísimos con un objetivo claro: resolver el enigma y poder mantenerse juntos.

- Una vez más para (S3-S6)

- Abril regresa a su casa para el funeral de su abuela y al reencontrarse con su antigua vida empieza a pensar en recuperar todo lo que dejó atrás cuando se marchó hace cinco años al extranjero en busca de un futuro. Director: Guillermo Rojas.

Este programa para estudiantes de español les brinda la oportunidad de mejorar sus habilidades lingüísticas y su conciencia cultural. El ESFF también ha preparado un conjunto de actividades posteriores al visionado, disponibles para que los estudiantes profundicen en las películas y practiquen el vocabulario.

Más información, programa completo y entradas: www.edinburghspanishfilmfestival.com

7th Edinburgh Spanish Film Festival: School Programme

The Edinburgh Spanish Film Festival is back for its seventh edition and it includes a School Programme aimed at Spanish Learning students.

Due to COVID-19, the regular format has changed to an Online Event: the film will be available for 48 hours. The way this would work would be through a link sent to teachers, allowing them access to watch the films in class within a set time.

In this edition, the School Programme films are:

- ‘Los Futbolísimos’ (P7- S2)

This group of schoolmates get into all kinds of adventures which

put their friendship to the test. They uncover a mystery that could

put an end to their football team. The time has come to make a

secret pact and to create ‘Footballest’ with a clear objective: to

solve the mystery and be able to stay together.

- ‘Una vez más’ for (S3-S6)

Abril left Daniel behind 5 years ago, when she decided to try her

luck in London. She is back home now, to bury her grandmother.

Walking the streets of what was her home with the man who was

her love, she realizes she has missed it all.

This programme for Spanish students gives them the opportunity to better their language skills as well as cultural awareness. ESFF has also prepared a set of post-film activities available for students to delve more deeply into films and practice vocabulary.

Tickets £25 per class. For tickets reservations and further information, please contact info.esff@ed.ac.uk

Further information, full programme and tickets: www.edinburghspanishfilmfestival.com

Ya puedes ver el documental ‘Entre dos tierras’ en línea

Entre Dos Tierras, un documental que trata sobre los retos emocionales de vivir en el extranjero, lo que se conoce como duelo migratorio, puede verse en línea en la plataforma Vimeo a partir de hoy.

Tras dos años de trabajo, sale a la luz el proyecto dirigido por Javier Moreno Caballero, que realizó la webserie Spaniards in London con la que consiguió numerosos reconocimientos internacionales.

El equipo técnico de Javier está compuesto por emigrantes españoles que viven desde hace años en Londres, y que se unen para el proyecto bajo el nombre de Catalejo Azul Producciones.

A través de más de 20 testimonios de jóvenes españoles, el documental hace un recorrido por la aventura migratoria de los millennials, aquellos que nacieron a partir de los 80, y que por diferentes motivos tuvieron que abandonar España y empezar una nueva vida en Reino Unido.

Desde un punto de vista realista y humano, el documental muestra de primera mano las pérdidas y ganancias a las que se han tenido que enfrentar durante su travesía migratoria, incluyendo la partida, estancia en el extranjero y retorno al país de origen.

Un relato sobre la migración contemporánea que hasta ahora no se ha mostrado en ningún proyecto audiovisual.

El proyecto cuenta con el apoyo del colegio de Psicólogos de Madrid y con la participación de Joseba Achotegui, reconocido psiquiatra que puso nombre al conjunto de pérdidas que acompañan a los migrantes en su andadura en el extranjero: Duelo Migratorio.

Junto con Celia Arroyo y Guillermo Fouce, también expertos en el tema, ayudarán a entender ciertos comportamientos que suelen experimentar los emigrantes.

El estreno tuvo lugar el pasado noviembre en el Kings College de Londres de la mano del Instituto Cervantes de Londres, y tras haberse cancelado las proyecciones programadas en varias ciudades europeas debido al COVID, Javier ha optado por el lanzamiento online a través de la plataforma de video Vimeo On Demand.