The Cosmography and Geography of Africa published today

Today Penguin Classics is publishing The Cosmography and Geography of Africa, by Leo Africanus, a Moroccan diplomat born in Granada, Spain. This is the first English translation in over 400 years of one of the greatest and most influential works of Renaissance literature.

Modern and lucid, this new translation is the first based on an undiscovered manuscript unearthed in Italy on the precipice of the Second World War, and is bound to transform the way we understand contemporary conceptions of Africa.

In 1518, al-Hasan ibn Muhammad al-Wazzan, a Moroccan diplomat, was seized by pirates while travelling in the Mediterranean. Brought before Pope Leo X, he was persuaded to convert to Christianity, in the process taking the name Johannes Leo Africanus. Acclaimed in the papal court for his learning, Leo would in time write his masterpiece, The Cosmography and Geography of Africa.

The Cosmography was the first book about Africa, and the first book written by a modern African, to reach print. It would remain central to the European understanding of Africa for over 300 years, with its descriptions of lands, cities and peoples giving a singular vision of the vast continent: its urban bustle and rural desolation, its culture, commerce and warfare, its magical herbs and strange animals.

Yet it is not a mere catalogue of the exotic: Leo also invited his readers to acknowledge the similarity and relevance of these lands to the time and place they knew. For this reason, The Cosmography and Geography of Africa remains significant to our understanding not only of Africa, but of the world and how we perceive it.

A copy of this book is available in our library.

Rutas del Londres español: Memoria de nuestros exilios

Os proponemos un paseo por la memoria del exilio español en el este de Londres para conocer lugares señeros de nuestros exiliados protestantes (S. XVI), liberales (S. XIX) y republicanos (S. XX).

El paseo estará guiado por Milagros Dapena-Collopy, guía acreditada “blue badge” en Londres desde 1997 y licenciada en turismo, que glosará cada uno de los lugares por los que pasemos en relación con las personalidades españolas exiliadas.

Esta ruta se circunscribe al este de Londres. El itinerario será el siguiente:

Bloomsbury

Comenzamos nuestro paseo en Bloomsbury, el gran distrito intelectual de Londres. Russell Square Station, London WC1N 1HX

El apartamento del escritor y periodista Manuel Chaves Nogales fue lugar de encuentro de otros exiliados españoles, periodistas, escritores, y políticos republicanos. En el mismo bloque vivió el escritor, poeta y académico Luis Gabriel Portillo. Russell Court – Woburn Place, London WC1H ONL

El antiguo hotel Lincoln’s hall, donde se alojó cuando llego a Inglaterra Josep Trueta, uno de los cirujanos militares más destacados del siglo XX. Reconocido internacionalmente por sus trabajos y aportación a la medicina. Royal National hotel, 38-51 Bedford Way. London WC1H ODG

El Museo Británico. En su biblioteca, Esteban Salazar Chapel tuvo la idea de escribir la crónica del exilio republicano en Gran Bretaña: su Perico en Londres. British Museum – Great Russell Street, London WC1B 3DG

En Bloomsbury Square se alojó un entusiasta de la literatura inglesa, Pío Baroja. Su novela La ciudad de la niebla es un ejemplo de anglofilia barojiana. Bloomsbury Square – London WC1

Holborn / Aldwych

Seguimos nuestro paseo atravesando parte del barrio jurídico de Holborn para llegar a Aldwych, donde se fundó el servicio mundial de la BBC en Bush House. Allí colaboraron varios de los exiliados españoles, destacando Arturo Barea. Bush House – 30 Aldwych, London WC2B 4BG

En King’s College trabajaron algunos de nuestros exiliados en el departamento de español. Rafael Martínez Nadal lo hizo durante cuarenta años. King’s College – Strand, London WC2R 2LS

City of London

En Fleet Street, la calle más emblemática para el mundo periodístico, tuvo su agencia de noticias Manuel Chaves Nogales. 76, Fleet Street, antigua agencia de noticias Atlantic Pacific Express, London EC4Y 1EU

Previamente, en sus talleres, se habían impreso trabajos de reformistas españoles del siglo XVI como Casiodoro de Reina, traductor de la influyente Biblia del Oso.

Terminamos nuestro paseo en un mundo aparte: el escondido barrio de Temple. En su iglesia, de origen templario, Antonio del Corro, otro de los reformadores del siglo XVI y autor de una gramática española para ingleses, fue el primer Reader. Temple Church – Temple , London EC4Y 7BB

Regístrate en nuestro evento de Eventbrite.

El Instituto Cervantes organiza una jornada cultural hispano-británica con ocasión de la visita de García Montero a Londres

El Instituto Cervantes de Londres organiza el jueves 3 de febrero una celebración de la literatura española y de los vínculos hispano-británicos que contará con la presencia del director del Instituto Cervantes, Luis García Montero. A lo largo de la jornada se inaugurará una ruta del exilio español en el este de Londres, se dedicará una biblioteca en homenaje al hispanista Trevor Dadson, se entregará un manuscrito –ahora custodiado por el Cervantes de Londres- a la Biblioteca Nacional de España, y se presentará la traducción al inglés del libro Wild creature, del poeta catalán Joan Margarit. La directora de la Biblioteca Nacional de España, Ana Santos, acompañará a García Montero en los actos de este día.

Ruta del exilio español en el este de Londres

El director del Instituto Cervantes participará en la primera ruta del exilio español en el este de Londres, con salida desde la estación de metro de Russell Square, en una comitiva liderada por el embajador de España, José Pascual Marco, y en la que no faltará el nieto del célebre exiliado Manuel Chaves Nogales, Antony Jones.

En el recorrido no faltarán parada expresa ni mención a españoles exiliados en Londres en lugares como: Russell Court (Manuel Chaves Nogales, Gabriel Portillo, Joan Gili), Lincoln’s inn (Josep Trueta), British Museum (Esteban Salazar Chapela), Kingsway (Pablo de Azcárate), LSE (Josep María Batista Roca), Bush House (Arturo Barea), Fleet Street (Casiodoro de Reina, Cipriano Valera) y Temple (Antonio del Corro).

Este paseo es la primera de una serie de rutas con guías cualificados que el Instituto Cervantes de Londres va a incluir en su programación para dar a conocer el legado de los españoles que vivieron y trabajaron en la capital británica.

Acuerdo de colaboración con la British-Spanish Society

García Montero firmará junto a Jimmy Burns Marañón, presidente de la British Spanish Society (BSS, por sus siglas en inglés) un acuerdo marco de colaboración entre el Instituto Cervantes y la centenaria organización hispano-británica. El acto tendrá lugar en la biblioteca del Instituto, en Temple.

Las áreas generales de colaboración contempladas en el acuerdo entre Cervantes y BSS son las siguientes: cooperación educativa y académica, estudios técnicos y de consultoría, proyectos de investigación y desarrollo tecnológico e innovación, y cooperación en programas europeos. Con la firma del acuerdo, el Instituto y la BSS afianzan una colaboración que viene de antiguo.

Dedicación del fondo antiguo de la biblioteca a Trevor Dadson

El fondo antiguo de la biblioteca del Instituto Cervantes de Londres, formado por unos 800 ejemplares de libros de viajeros británicos por España y de libros antiguos, será dedicado a la memoria del célebre hispanista y catedrático británico Trevor Dadson (1947-2020). A partir de ahora, este fondo llevará el nombre de Colección Trevor Dadson – Trevor Dadson Collection.

El acto tendrá lugar en el Instituto Cervantes de Londres, con la presencia de su viuda, Ángeles Dadson, así como de la presidenta de la Asociación de Hispanistas de Gran Bretaña e Irlanda (AHGBI), la catedrática Catherine Boyle. El profesor Dadson presidió la AHGBI entre 2011 y 2015.

Dadson fue un académico de currículo extraordinario, un mentor y maestro de generaciones de estudiosos y -ante todo- un enamorado de España y la cultura española. Este historiador de la literatura fue autor de importantes estudios sobre la poesía del Siglo de Oro y los moriscos. Además, Dadson dejó un gran número de discípulos en el mundo académico. Con la dedicación de esta biblioteca de viajeros británicos por España, el Instituto Cervantes quiere homenajear, en la figura de Dadson, a la rica tradición de hispanistas de Reino Unido.

Devolución del manuscrito a la Biblioteca Nacional de España

Por la tarde, en la Embajada de España en Reino Unido, tendrá lugar un acto muy especial: la devolución de un manuscrito de finales del S. XVI titulado Abusos de comedias y tragedias a la Biblioteca Nacional. Para la recepción del documento se trasladará a la Embajada la directora de dicha institución, Ana Santos, junto a Luis García Montero.

El manuscrito, que aborda el tema, típico en la época, de la moralidad del teatro, consta de 24 páginas en 12 folios. Se ha probado que el documento formó parte de las colecciones de la Biblioteca Nacional hasta mediados del siglo XIX, momento en el que desapareció de los fondos de la institución. Siglo y medio más tarde, el catedrático emérito de UCL Ángel María García Gómez, lo encontró en una librería anticuaria del condado de Wiltshire y procedió a su compra. Con este acto de entrega a la Biblioteca Nacional se cumple el deseo del profesor García Gómez de que el valioso manuscrito vuelva a la que fue su casa.

Traducción al inglés de Wild creature, libro de Joan Margarit

La jornada culminará con la presentación, en la misma Embajada y acto seguido, de la traducción al inglés del libro Wild Creature (Animal de Bosc), del poeta catalán Joan Margarit (1938-2021), que contó con el apoyo económico del Instituto Cervantes de Londres para su traducción.

Wild Creature, publicado por Bloodaxe Books en Reino Unido, ha sido traducido del catalán al inglés por Anna Crowe, quien participará en el acto, junto al editor, Neil Astley, y el nieto de Margarit, Eduard Lezcano. La presentación se cerrará con un recital de poemas de Margarit en catalán e inglés, a cargo de Marc Bosch y Alex Mugnaioni, respectivamente.

Margarit, nacido en Sanahuja, Lleida, obtuvo el Premio Cervantes en 2019 por “su obra poética de honda transcendencia y lúcido lenguaje siempre innovador”, con el que “ha enriquecido tanto la lengua española como la lengua catalana, y ha representado la pluralidad de la cultura peninsular en una dimensión universal de gran maestría”.

Con los actos previstos para el día 3 se quiere, en opinión del director del Instituto Cervantes en Londres, Ignacio Peyró, “honrar la memoria española de la ciudad, dar a conocer la diversidad de nuestra poesía, celebrar el hispanismo británico y subrayar la fuerza de los lazos culturales entre Gran Bretaña y España”.

Celebramos el Día Internacional de la Traducción con James Womack

Desde el Instituto Cervantes de Londres nos sumamos a las celebraciones del Día Internacional de la Traducción charlando con James Womack, poeta y traductor literario de ruso y español.

Womack estudió literatura inglesa y lengua rusa en la Universidad de Oxford, donde obtuvo un doctorado con una tesis sobre ideología en la traducción de W.H. Auden. Continuó formándose como traductor en las universidades de Reikiavik y San Petersburgo. Ha sido docente en la Universidad Estatal de Moscú (1997-98), la Universidad de Oxford (2004-2006; 2009), la Universidad de Cambridge (2007-2008) y la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (2010-2014). Actualmente enseña en el Máster de Escritura Creativa de la Universidad de Oxford.

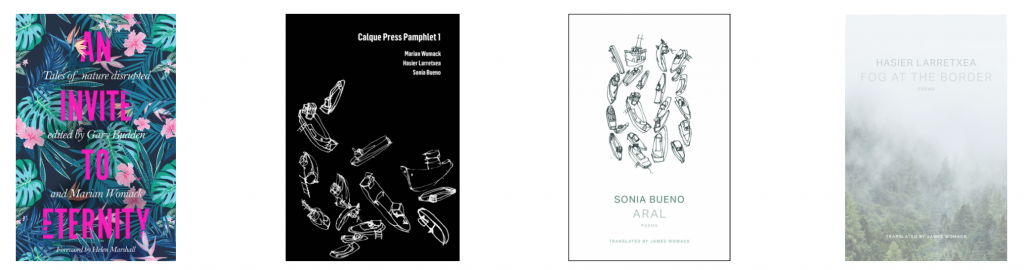

Womack ha publicado dos colecciones de poesía, Misprint (Carcanet 2012) y On trust (Carcanet, 2017, preselección del Dylan Thomas Award), además de una colección de versiones poéticas de Vladímir Maiakovski en traducción, titulada Vladimir Mayakovsky and Other Poems (Carcanet 2016), elegida como una de las traducciones del año por la Poetry Book Society.

En 2016 fue seleccionado como traductor entre los finalistas de la iniciativa PEN Presents para la promoción de la literatura europea. Como traductor ha publicado versiones de Alexander Pushkin, Antón Chejov, los hermanos Strugatski, Sever Gansovski, Roberto Arlt, Manuel Vilas, Silvina Ocampo y Sergio Del Molino, entre otros.

Es co-traductor, junto con la poeta española Ana Gorría, de Travesía Escéptica (Diputación Provincial de Málaga 2010), una selección de la poesía de John Ash, y ha publicado versiones de poetas contemporáneos españoles, entre ellos Hasier Larretxea, Sonia Bueno, Martín López-Vega y Sofía Rhei.

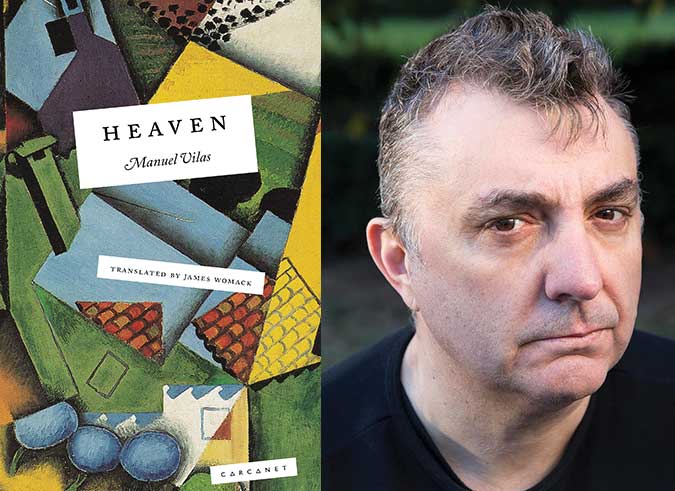

Se publica en inglés Heaven, de Manuel Vilas, con la editorial Carcanet Press, ¿cómo ha sido la traducción?

Hay dos respuestas posibles a esta pregunta, la personal y la que se refiere a la técnica. Respecto al apoyo personal por parte del autor hacia la traducción, lo cual es siempre algo a tener en cuenta cuando se traduce a un autor vivo, Manuel Vilas ha apoyado el proyecto desde el principio, y se ha mostrado extremadamente colaborador. En lo que se refiere al aspecto técnico de la traducción, esa pregunta resulta algo más compleja. Vilas es un poeta que parece muy asequible desde un plano superficial. Pero cuando comienzas a ahondar de lleno en las estructuras que maneja, tanto en su uso del idioma como en su pensamiento, sus ideas, entonces empiezas a darte cuenta de lo compleja y sutil que resulta su forma de pensar. Estamos frente a un poeta que, a primera vista, parece “fácil” de traducir, pero que al final acaba por llevarte días, incluso semanas, encontrarte satisfecho con tu version de un poema. Desde ese punto de vista, la traducción fue extremadamente compleja, pero también una fuente inacabable de satisfacción.

Usted es traductor de español, pero también de ruso. ¿Nos puede contar cómo surgió su interés en lenguas tan dispares?

Se trata simplemente de una cuestión de amor. Mi primer amor desde el punto de vista académico fue por la lengua rusa, que empecé a estudiar a los catorce años. Siempre me he sentido atraído por la nieve, los paisajes vacíos de la estepa, la idea de un país que abarcaba tanto espacio en el mapa. Más tarde, comenzó a interesarme la literatura rusa, en especial la poesía. Mi amor por España fue inesperado: en 2002 conocí y me enamoré de una mujer de Cádiz, hoy mi esposa, y ella me introdujo al idioma y a la literatura española, que me resulta ahora igual de fascinante. Vivimos en España entre 2008 y 2017, años en los que desarrollé un gran afecto por el país y su cultura, tanto o mayor que el que había sentido y siento por la cultura rusa.

Ayuda a ejecutar Calque Press, que se concentra en la poesía, la traducción y el medio ambiente. ¿Cómo les ha afectado la pandemia del Covid?

Creo que cualquiera que esté ligado a una pequeña editorial siempre va a encontrarse a la merced de factores externos. Mi esposa y yo fuimos los fundadores de otra pequeña editorial en Madrid en 2008: lanzar aquel proyecto en mitad de una crisis mundial económica tampoco fue sencillo. Hemos encontrado dificultades similares con la pandemia del Covid-19: nos encontrábamos en las primeras etapas con varios proyectos editoriales, los cuales se han visto retrasados, han sufrido cambios, o incluso han sido cancelados. No teníamos previsto publicar muchísimos libros, pero este año, en lugar de los cuatro que teníamos previstos, solo publicaremos uno. Esto no significa que las otras tres ideas han sido abandonadas, sino más bien que nos vemos obligados a hacer las cosas de manera más pausada durante los próximos meses. También acabamos de ser padres, por segunda vez y en mitad de la pandemia, lo cual también ha afectado un poco nuestro ritmo.

¿En qué otras traducciones del español está trabajando?

Justo antes del confinamiento debido al Covid-19 terminé una traducción de la que me siento muy orgulloso, una nueva versión de Camilo José Cela La Colmena. Ahora mismo estoy revisando las pruebas de imprenta, y será publicada por NYRB Classics en 2021. En lo que concierne a Calque Press, esperamos publicar autores peninsulares de poesía. El fascinante poemario experimental del Sonia Bueno, Aral, se publicó a principios de 2020, y actualmente estoy terminando mi traducción del complejo y emotivo poemario de Hasier Larretxea Niebla Fronteriza, que espero publicaremos en Calque en los próximos meses. Hasier es muy conocido en España por sus performances poéticas, que tienen lugar con su padre, conocido txapeldun, en las que se mezclan la naturaleza y la tradición con la poesía más innovadora. Ojalá podamos traerlos al Reino Unido para compartir su visión. Recientemente he empezado a interesarme por la poesía de Leopoldo María Panero, y estoy buscando editor en Inglaterra para publicar una traducción de su obra.

Presentación de ‘Heaven’: los poemas de Manuel Vilas ya pueden ser recitados en inglés

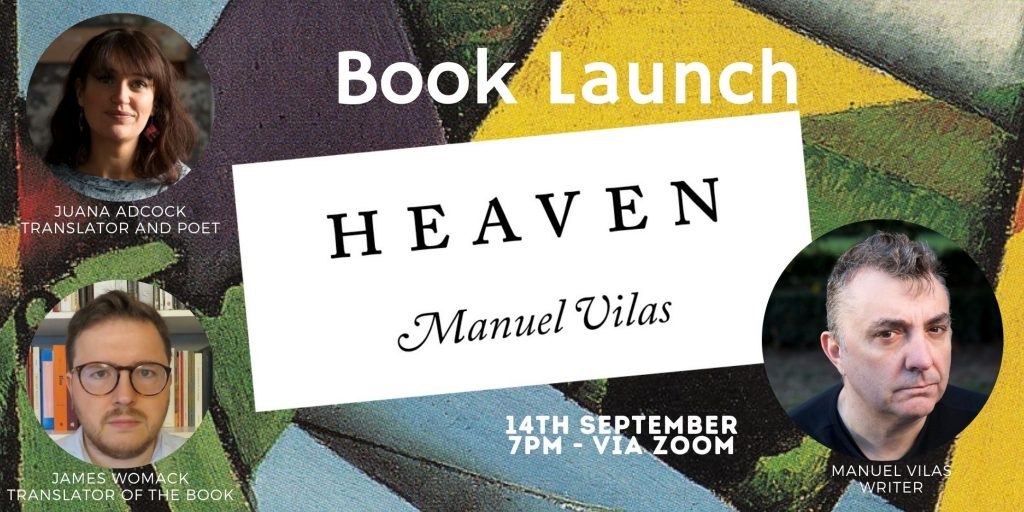

El escritor español Manuel Vilas participó en la presentación de la primera traducción al inglés de su libro de poesía ‘Heaven’, en un evento en línea organizado por el Instituto Cervantes de Londres, como parte de su programa cultural de septiembre, en colaboración con la prestigiosa editorial Carcanet Press.

Ante el centenar de personas que se sumaron a la actividad, Vilas estuvo acompañado por el traductor de la obra, James Womack, y por el director del Instituto Cervantes de Londres, Ignacio Peyró, en un acto moderado por la poeta y traductora Juana Adcock.

Los poemas de Vilas cuentan historias en las que el hablante se mueve quijotescamente a través del mapa y entre romances. Su instinto por el ritmo le da al lector un firme sentido del lugar y el tono. Universales en sus inquietudes, abarcando el amor y el fin del amor, la vida y el fin de la vida, los poemas también son decididamente españoles en su forma de hablar, sin rodeos, con humor, siempre alerta a lo fantástico.

Peyró destacó la importancia de dar a conocer la literatura en español en todos sus ámbitos: “si la narrativa y la dramaturgia tienen un éxito notable en Reino Unido, hay que comunicar también el magnífico momento de nuestros poetas y ensayistas”.

Primera traducción al inglés de sus poemas

La editorial independiente británica Carcanet Press, que publica una lista completa y diversa de poesía moderna y clásica en inglés, apuesta ahora por la traducción de ‘Heaven’ (El cielo, 2000), un libro con poemas alimentados temáticamente por el alcohol, la muerte y el sexo, se embarcan en vuelos megalomaníacos de fantasía.

Vilas reconoce la importancia de esta publicación porque es su primer libro de poemas traducido al inglés: “Creo que en la mente de todo escritor está la idea de la traducción de tu obra al inglés, ya que es la lengua que hace de colinde universal”.

El escritor destacó la pasión literaria y el dominio de las dos lenguas de James Womack a la hora de traducir sus poemas, definiéndolo como el “temperamento más idóneo” que tiene que tener todo traductor.

Una traducción extremadamente compleja y una fuente inacabable de satisfacción

“Vilas ha apoyado el proyecto desde el principio, y se ha mostrado extremadamente colaborador”, reconoce Womack, si bien puntualiza que en lo que se refiere al aspecto técnico de la traducción, Vilas es un poeta que “parece muy asequible desde un plano superficial, pero cuando comienzas a ahondar de lleno en las estructuras que maneja, tanto en su uso del idioma como en su pensamiento y sus ideas, entonces empiezas a darte cuenta de lo compleja y sutil que resulta su forma de pensar”.

Womack apunta que fue una “traducción fue extremadamente compleja, pero también una fuente inacabable de satisfacción”. Traductor del ruso, lengua que empezó a estudiar a los catorce años, su amor por España fue inesperado: en 2002 conoció y se enamoró de una mujer de Cádiz, quien le introdujo al idioma y a la literatura española, la cual le resulta ahora igual de fascinante.

Womack subraya como cualquiera que esté ligado a una pequeña editorial siempre va a encontrarse a la merced de factores externos, como la actual pandemia sanitaria. De hecho, su esposa y él fueron los fundadores de una pequeña editorial en Madrid en 2008 y lanzar aquel proyecto en mitad de una crisis mundial económica tampoco fue sencillo.

Justo antes del confinamiento, Womack terminó una traducción de la que se siente muy orgulloso, una nueva versión de la La Colmena de Camilo José Cela. En la actualidad, está en proceso de revisión y será publicada por NYRB Classics en 2021.

‘Heaven’ online book launch, by Manuel Vilas

Online conversation on the ocassion of the launch of ‘Heaven’, by Manuel Vilas, organized by Instituto Cervantes London, in collaboration with Carcanet Press.

Participants: writer Manuel Vilas, James Womack (translator of the book) and Juana Adcock (poet and translator)

Monday, September 14th at 7:00 pm. via Zoom. In English. Book your place here.

A collection of dark, funny Iberian poems about drinking, sex and death.

Manuel Vilas speaks in the voice of bitter experience, an experience which seems intent on sending him up. He is a novelist as well as a poet, and his poems tell stories as the speaker moves quixotically across the map and between romances. His instinct for rhythm gives the reader a firm sense of place and tone. Universal in their concerns, taking in love and the end of love, life and the end of life, the poems are also resolutely Spanish in how they speak – bluntly, humorously – always alert for the fantastic.

This is the first translation of Vilas’s two major collections Heaven (El cielo, 2000) and Heat (Calor, 2008) into English. Thematically fuelled with alcohol, death and sex, they go off into free-wheeling megalomaniacal flights of fantasy. The translator, James Womack, has won prizes for his versions of Vilas and of the Russian poet Mayakovsky.

James Womack was born in Cambridge in 1979. He studied Russian, English and translation at university, and received his doctorate, on W.H. Auden’s translations, in 2006. He lived in Madrid from 2008 to 2017, and now teaches Spanish and translation at Cambridge University. He is a freelance translator from Russian and Spanish, and helps run Calque Press, which concentrates on poetry, translation and the environment. His debut collection of poems, Misprint, was published by Carcanet in 2012, and On Trust: A Book of Lies came out in 2017.

Juana Adcock is a poet, translator and performer. Her Spanish-language poetry collection, Manca, explores the anatomy of violence in the Mexican drug war and was named by Reforma‘s distinguished critic Sergio González Rodríguez as one of the best books published in 2014. In 2016 she was named one of the ‘Ten New Voices from Europe’ by Literature Across Frontiers, and she has performed at numerous literary festivals internationally. Her English-language debut, Split (Blue Diode Press, 2019) was awarded the Poetry Book Society Choice.

Once you have booked your ticket, a link will be emailed to you on the day of the event. Please check your spam folder, and if you have not had the link by 3 p.m. on the day, please email prenlon@cervantes.es with your order confirmation number.

«Spending so much of my life in Spain means I really appreciate the moment, just enjoying where I happen to be»

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our ninth guest, Annie Bennett, specialises in writing about Spain and is usually mooching around the country searching for the perfect tapas bar.

Bennett writes for The Daily and Sunday Telegraph and she is their Madrid expert. She has also contributed to The Guardian and Observer, The Times, The Financial Times, The Sunday Times Travel Magazine, The Independent and Independent on Sunday, Travel Weekly, Conde Nast Traveller, Tatler, Elle, Red, Time Out & various airline magazines.

Her latest book is Insight Explore Madrid (January 2018) and she has also written National Geographic Traveler Madrid, Blue Guide Madrid, Blue Guide Barcelona and Art Shop Eat Barcelona. She has won a few awards over the years, including Spain Travel Writer of the Year.

– You describe yourself as a food & travel writer mooching around Spain for Telegraph & other UK nationals. How did you get to this job? Why Spain?

I studied Spanish and German at the University of Westminster, specialising in translation and interpreting. As I had lived in Cologne for a couple of years before doing my degree, my German was much stronger than my Spanish, so after graduating I went to live in Madrid to try and improve it. This was the early 1980s and I was lucky enough to become friends with some of the key figures of the Movida, which opened the door to the dynamic creative scene. I became quite involved in the art world and started translating for galleries and museums. It wasn’t long before I started writing, just because I knew such interesting people really. I first interviewed Pedro Almodóvar back in 1985!

I moved back to London in 1992 for a few years, but my links with Spain became stronger than ever when I started travel writing. I wrote the Blue Guides to Madrid and Barcelona and started contributing to national newspapers and magazines. And I have just kept going with articles and books – my list of places in Spain I want to write about just gets longer and longer.

– You are based between Madrid and South Wales, is that the perfect combo?

My family is in South Wales and I do a lot of my writing here. I love the beaches of the Gower Peninsula, which are actually quite similar to those on the Rías Altas in Galicia. I’ve been here during lockdown and it is wonderful to be able to walk along the beach every day and explore Gower without tourists.

As I write about Spanish tourism for British people, it really helps to live a caballo between the two countries, to keep my finger on the pulse of what people are talking about and what they are familiar with in Spain, whether culture, gastronomy or tourism. I can’t assume that everyone knows who Velázquez or Rosalía are, for example. Now everyone buys chorizo in the supermarket and chucks it in everything (I’m not mentioning paella), but that certainly wasn’t the case 20 years ago. I’m currently reading María José Sevilla’s brilliant new book, Delicioso: The History of Food in Spain; we really needed a serious book in English about Spanish food and I’m really enjoying having the time to read it during lockdown.

– What places do you like visiting when you are in Spain? What topics do you like covering?

Madrid is home to me and I am champing at the bit to get back there. Something that has really surprised me during lockdown is how much I’m missing it and I have cried quite a few times watching videos and news reports of what is happening there.

But as 2020 is the centenary of the death of Benito Pérez Galdós, I am spending a lot of time in Madrid, albeit just in my head, by rereading Fortunata y Jacinta and his other wonderful novels. It is frustrating not to be able to take part in the walks and other events in the city organised to commemorate the anniversary, but as I know the streets and locations so well, it is almost like being there.

I love Valencia too and go a few times a year. I think it is a very underrated city, for culture and the urban beaches but more than anything the food. I could happily eat a rice dish for lunch every day. The produce there is so good and varied; I think it has one of the most dynamic gastronomic scenes in Spain, with fantastic chefs such as Ricard Camarena, Quique Dacosta and Bernd Knöller, to mention just a few. I’ve been going to Casa Montaña in the Cabanyal neighbourhood by the sea for more than two decades and it is my favourite tapas bar in Spain.

I find the area around Vejer de la Frontera on the Costa de la Luz quite intoxicating. The food scene is really interesting, there are fabulous beaches and I always seem to have a glass of sherry in my hand. One of the most exciting and memorable experiences I have ever had as a travel writer was being on one of the almadraba boats to witness the catch of bluefin tuna at close hand. I really enjoyed writing about this fascinating tradition – and eating just about every part of the tuna in the El Campero restaurant in Barbate.

I go the Hay Festival in Segovia every year, although I’m not sure if it is going to be possible this September. It is always one of the most enriching experiences of the year and listening to writers and artists talk about their work in convents, courtyards and gardens is just magical.

Lanzarote is a favourite too, although I hardly ever get to lie on a beach there. I have been writing about the ecotourism scene for the last decade or so and took part in the Saborea Lanzarote gastronomic festival last year. The cheeses and wines produced on the island are spectacular.

– How has the experience been? What do you enjoy the most about Spain?

Spending so much of my life in Spain means I really appreciate the moment, just enjoying where I happen to be. I love being in places some people consider unfashionable or not cool. I don’t care about that; in fact it’s a positive advantage to me. I’ve got a long list of towns in this category to visit or revisit when we can travel again. Getting a taste of how people just quietly go about leading very enjoyable lives without having to shout about it, in places that don’t get written about much, is one of the best things about Spain for me. I am always singing the praises of Soria and Jaén and have written several articles about the extraordinary cultural heritage of Alcalá de Henares.

– You visit places off the beaten track, could you tell us your favourite spots?

I’ve been a regular visitor to the Alpujarras for a long time, ever since I became fascinated by this magical mountain area after reading The Silence of the Sirens by Adelaida García Morales. She captured the hypnotic atmosphere of the astounding landscape so well. I was thrilled a few years ago to actually meet a curandera while walking down a track with a friend who lives there, as these local faith healers play an important part in the book.

Of course, the Alpujarras have become much more well known as so many people have read the wonderful books by Chris Stewart, since his best-selling Driving over Lemons was published two decades ago. Somewhere that still feels remote, however, is Babia, in the north-west of León. I had been reading about the area for years before I actually made it there, mostly in books and articles by Julio Llamazares and Luis Mateo Díez.

More recently, I was lucky enough to spend some time just over the border from Babia in the Somiedo area of Asturias, where brown bears prowl around the mountains. Getting up before dawn to go and spot them with local experts was a brilliant experience.

– You wrote an article with 20 reasons why British travellers will all return to Spain when this is finally over: boozy lunches, fast trains, slow trains, jamón, prawns, aperitivos, paradors, beaches… are you ready to go back?

While I am dying to return to Spain, I think I’m going to see how the situation develops as I am a bit wary about the potential health risks involved with being in airports and flying. I just want to be there without having to do the travelling really. I’m thinking it might be a good plan to enjoy the Gower beaches over the summer and start my Spain explorations again from September, although I’m not sure I’ll be able to wait that long.

– In Spain we have rural houses all around the country, have you ever stayed in one? Do you have any favourites?

As I review so many hotels, I don’t get to stay in as many rural places as I would like. I am however a big fan of rural tourism and have been writing about it for more than 20 years. There are so many extraordinary places to stay in the countryside and on lesser-known parts of the coast. I’ve stayed in some gorgeous houses and small rural hotels in Cabo de Gata in Andalucía, Cantabria, Asturias, Galicia and the Canary Islands. I stayed in an amazing house in Lanzarote that was actually a converted water cistern but looked like something from a James Bond film.

– Now it is easier to find Spanish ingredients and products in the UK. Which ones were always the hardest ones to find? Which ones are always in your larder?

I don’t actually buy that many Spanish products in the UK as I am usually – before the pandemic obviously – travelling backwards and forwards so frequently. Looking in my cupboards, I have pimentón, saffron, jars of good tuna and tins of sea urchin paté and anchovies. There is always a good supply of turrón and Paladín hot chocolate, which are my mother’s favourites. I always have quite a few olive oils from different parts of Spain as well as sherry vinegar. I seem to have got through most of my stock of Spanish wines and sherries though….

It is wonderful that now it is easy to get excellent olive oils, ham, cheeses, paella rice and wines from fantastic producers, delis and restaurants such as José Pizarro and Brindisa. Here in Wales we are lucky to have the Bar 44 and Ultracomida groups, who are absolutely passionate about Spanish produce and have been doing some great live tasting events during lockdown.

Luke Stegemann: “En España descubrí una Europa que me habían ocultado”

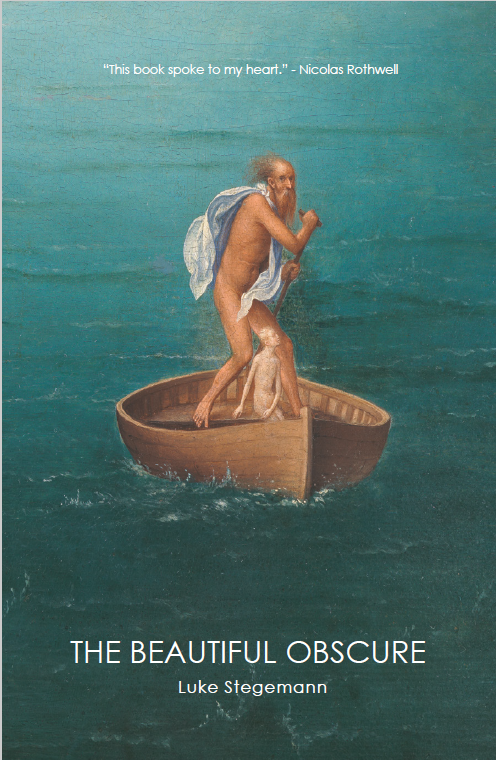

Hijo de cura anglicano y criado en el corazón rural de Nueva Gales del Sur, el australiano Luke Stegemann descubrió España por sorpresa en los años 80. Enamorado del país, no tuvo más remedio que volver a vivir en él, y desde entonces compagina temporadas en Australia y temporadas en España. Con una larga carrera como profesor, traductor y periodista -The Adelaide Review, The Melbourne Review-, y popular en las redes por su afecto a todo lo español, Stegemann ha escrito dos libros de tema completa o parcialmente español: The beautiful obscure (Transmission Press, 2017) y Amnesia road: landscape, violence and memory (NewSouth Publishing, febrero 2021).

-En The Beautiful Obscure se unen su condición de australiano que descubre España y la reflexión sobre los encuentros y lejanías entre ambos países en la Historia. ¿Qué atrae a un australiano, allá por los 80, a lo español?

Tuvo algo de fortuito. Viajaba por Europa tras terminar mi primera carrera y no había planeado pasar más de unos días. Sin embargo, una vez en España, sentí una atracción inmediata, a diferencia de lo que sentía, por ejemplo, en Grecia, Italia, Francia o Alemania. Los dos o tres días que había planificado pasar allí se convirtieron en un mes a medida que viajaba cada vez más por el país. Estamos hablando de 1984, y de una España que en muchos aspectos ha desaparecido por completo. La sensación más evidente fue la de descubrir una Europa de la que nunca me habían hablado. Era como si una sección entera del continente, cuya historia creía haber estudiado, hubiera estado oculta.

Así que la atracción era hacia lo desconocido, pero no era tan simple como la experiencia clásica de «orientalización» de «lo exótico». De inmediato quedó claro que esto era parte de mi propio patrimonio cultural, parte de la historia del continente de mis antepasados. Inmediatamente pensé: «¿Cómo no supe esto?» y luego, «¿Cómo puedo vivir aquí?» Cuando regresé a Australia y expliqué mi plan para vivir en España lo antes posible, mi familia y amigos no daban crédito. España aún no se había unido a la UE y estaba discutiendo su entrada en la OTAN. Dos años después, ya estaba en España como profesor de inglés.

Una cosa importante para mí es enfatizar que al ser australiano, a diferencia de británico o norteamericano, creo que aporto una perspectiva diferente sobre la historia y la cultura española. Vengo del «sur», del Pacífico y de una colonia europea: todo esto influye en mi manera de entender España y su lugar en el mundo. Ninguna parte de Australia fue colonizada por España (aunque podría haberlo sido), ni Australia ha tenido ningún conflicto con España. En ese sentido, no tenemos «historial», ni «equipaje» como países asociados. La gente a menudo habla de la similitud (hasta cierto punto, no debería ser exagerada) de carácter entre australianos y españoles, de gente muy amistosa y, debo decir, una reputación de tener una actitud desafiante ante la autoridad, que es principalmente una fachada y no una realidad. Ciertamente, existe la determinación en ambos países de disfrutar la vida y llenarla con el mayor placer posible, aunque los australianos son más conservadores socialmente.

-Durante siglos, la relación de España con Australia parece haber sido la historia de una frustración: ni los barcos de la aventura imperial ni los de las expediciones científicas encontrarían acomodo permanente en sus costas. A la vez, ese también parece ser el caso de Australia con España: inevitable pensar en ese verso de Ted Hughes a Sylvia Plath, en el que le dice que en su escuela nunca le hablaron de España…

En Australia, España siempre ha sido descuidada como tema de estudio. Esto se debió durante muchos años a la imitación australiana de la educación británica con todos sus prejuicios culturales y geopolíticos. En las últimas cuatro décadas nos hemos alejado de la órbita imperial británica y Australia se ha posicionado conscientemente como una potencia regional de Asia. Para ser un país «anglófono», hay un nivel muy alto de «alfabetización de Asia» en Australia. Dicho esto, salimos del paraguas británico para convertirnos en un aliado fiel y algo servil de EEUU, cuya cultura ha llegado a abrumar a la nuestra.

España es un destino turístico popular, aunque me desespera la cantidad de australianos que creen que visitar Barcelona y San Sebastián constituye «visitar España». Muy pocos aprovechan la oportunidad para explorar aquellas regiones que para mí son lo más destacado: Madrid; los pueblos de Zamora, Soria y Segovia; el Maestrazgo, las colinas de Jaén, la Tierra de Campos, sin olvidar los caminos de Toledo y Ciudad Real, a través del territorio del Quijote …

Madrid es un caso interesante en este punto. Siempre me han fascinado aquellos extranjeros a los que no les gusta. Para mí, Madrid es una concentración de tantas líneas de influencia histórica, cultural y política que es indispensable como punto de referencia. Por eso he tratado de comparar en mi libro momentos de la historia de Madrid con Australia. Ahí están los navegantes que, en época de Felipe III, reclaman atención para esa tierra, sin que les hagan caso. O cómo Carlos III muere en 1788, justo cuando los británicos fundaban lo que hoy es Sidney. Para mí, estas no son simplemente coincidencias; son líneas paralelas que fluyen a través de la historia, que no necesariamente se tocan en ningún punto, pero que de alguna manera influyen entre sí. Es por eso que sentí que las historias entrelazadas de Australia y España eran una gran historia no contada.

El poema de Ted Hughes que cita usted es un ejemplo clásico de esa interpretación de España a mediados del siglo XX desde el Atlántico Norte. Una España en blanco y negro, de clichés de la época franquista y esencialismo orientalista, que ha envejecido mucho. Esto, si me lo permiten, es la opinión de España que muchos australianos no tienen, porque no tenemos esos siglos de comparación cultural (y, a veces, de condescendencia). En The beautiful obscure no he mencionado el fútbol o las corridas de toros y muy pocas menciones al flamenco. Esto no se debe a que no aprecio y disfruto la singularidad cultural de cómo se realizan estas cosas en España, sino a que quería escribir un libro que evitara los comentarios habituales de las publicaciones.

Por cierto, y a propósito de la cuestión de la leyenda negra: al tratar de evitar los clichés anteriores, es innegable, al menos en mis lecturas culturales y políticas, apreciar un cierto tono despectivo hacia España que creo que atraviesa mucho pensamiento anglófono. Pero decirlo es invitar a la controversia. Uno puede creer que España fue maltratada por quienes la siguieron y que escribieron sus propias versiones de la historia como los «vencedores culturales», cuya influencia se extiende tanto en nuestro mundo contemporáneo. Uno puede apreciar esto y lo entiendo, sin caer en las teorías de la conspiración franquista de que un complot masónico y comunista en todo el mundo estaba tratando de destruir España. Pero he visto, con los recientes debates en torno a Roca Barea, que marcar la leyenda negra como algo real, puede etiquetarte como reaccionario, como franquista, lo cual me parece absurdo.

-¿Cómo expresar un amor por la cultura española e invitar a otros a sumergirse en ella, sin que tengan el acceso que ofrece el idioma?

A veces, la literatura y la música popular pueden ser de más difícil acceso para los extranjeros. Por esta razón, en mi libro y fuera, profundizo en el mundo del arte como un lenguaje más universal. Además de maestros obvios como Goya y Velázquez, quería que la gente conociera a algunos de mis pintores favoritos: Zurbarán, Sorolla y Zuloaga. Me cuentan mucho sobre España, y luego específicamente sobre el catolicismo, o Valencia, o Castilla. También quería expresar algunas opiniones «controvertidas»: nunca me ha gustado mucho el arte de Dalí, o de Picasso, o de Gaudí. Siempre he preferido Ribera a Velázquez. Estos son solo gustos personales. Otros favoritos son Juan de Juanes, Luis Morales, Alonso Cano, los románticos del siglo XIX y los pintores de la historia … Y quizás por encima de todos ellos, para mí, está El Greco. En verdad, el más grande.

Para mí, esta concentración en lo que es en gran medida, aunque no exclusivamente, arte religioso, es deliberada. Vivimos en una época en que la Iglesia Católica ha sufrido un enorme daño de reputación; en Australia esto es muy pronunciado. Destaco en el libro que defender el catolicismo es difícil de vender hoy en una sociedad secular y en muchos sentidos enojada. Sin embargo, existe (para alguien criado en los anglicanos como yo) una clara distinción entre la Iglesia católica como institución y el catolicismo en sí mismo, como un sistema de creencias que ha sido la fuerza motriz o la inspiración de gran parte del arte y la poesía más importantes de los últimos 500 o más años. Es este elemento del catolicismo lo que deseo celebrar; es un juicio estético, no moral.

–En España también tenemos nuestros clichés sobre Australia.

Cuando viví en España por primera vez, la ignorancia de Australia era casi total, y lo mismo era cierto en Australia con respecto a España. A finales de los años 80, el cliché de ‘Crocodile Dundee’ fue algo con lo que, como todos los australianos en el extranjero, tuve que vivir mucho tiempo. Con los años, esta situación ha cambiado drásticamente, pero Australia sigue siendo algo desconocido. Internet pone a la vista todo el mundo, pero todavía hay preguntas sobre la naturaleza de Australia: ¿Cómo de grande es realmente? ¿Hay tantos animales e insectos peligrosos? ¿Sigue siendo una colonia británica? ¿Cómo es de asiático? Creo que mucha gente está sorprendida por lo multicultural que es Australia y la gran diversidad de nuestra población.

Otro factor importante para superar la ignorancia ha ocurrido en la última década: por un lado, cada vez más jóvenes australianos hacen en España una parte esencial de sus viajes internacionales; mientras que después de la crisis financiera de 2008, miles de jóvenes españoles, sobre todo profesionales altamente calificados, encontraron oportunidades de trabajo en Australia. Esto fue una especie de «fuga de cerebros» para España, pero Australia se ha beneficiado enormemente. Los españoles a menudo se encuentran entre los principales científicos e investigadores en Australia en la actualidad.

-Australia y España afrontaron una cuestión similar: qué hacer con las poblaciones originarias.

Si, absolutamente. Pero con al menos dos diferencias: en primer lugar, en Australia este problema todavía está con nosotros, a pesar del enorme progreso que se ha logrado. De hecho, muchas personas argumentarían (y yo estaría de acuerdo) que el largo y lento proceso de reconciliación con la población indígena sigue siendo el mayor desafío de Australia como nación. En segundo lugar, en Australia, la presencia indígena no forma parte de un «imperio de ultramar», sino que forma parte del tejido cotidiano de nuestra nación. De hecho, el desarrollo de Australia, tal como lo conocemos, sólo fue posible gracias al desplazamiento de la cultura indígena.

Siempre he creído que una colonización española de Australia, sin ser ni mejor ni peor, habría tenido resultados diferentes para la población indígena. Hubiera habido más matrimonios mixtos y un esfuerzo significativamente mayor para registrar y preservar algunos de los aproximadamente 200 idiomas que existían aquí antes de la colonización, la gran mayoría de los cuales se han perdido.

–El arte, al que tantas páginas dedica en su libro, parece habernos aproximado, más allá de los estudios sobre Goya de Robert Hughes, hasta ahora “el” hispanista australiano…

Es interesante: creo que su libro sobre Goya fue uno de los mejores, mientras que su libro sobre Barcelona fue uno de los más débiles: fuera de sus áreas de especialización de arte y modernismo, en realidad no daba la sensación de haber «vivido» Barcelona. En todo caso, yo invitaría a los españoles a explorar el arte australiano, que es tan diverso como el propio país. Aunque a menudo ha seguido las tendencias europeas y norteamericanas, sin embargo, también ha traído un magnífico grupo de artistas al escenario mundial. También tiene una creciente importancia para muchos australianos, de todos los orígenes, el mundo diverso, original y profundo del arte indígena.

-Cerramos. Han sido 35 años desde que se encontró con España…

Lo digo en mi libro. Tantos años sumergiéndome en el universo español han resultado enriquecedores en más formas de las que puedo contar, pero sobre todo, hay algo más que me resulta difícil de definir, aunque que sé que es cierto. Me ha hecho una mejor persona. Esto tal vez sea cierto para todos los que aprendemos a vivir en dos culturas y dos idiomas: nos hacemos personas más sabias, más tolerantes y, espero, más compasivas. Por esto, siempre digo, y lo creo sinceramente, que estoy en deuda con los españoles.

Luke Stegemann: «In Spain I discovered a Europe I had never been told about»

Luke Stegemann was born in Brisbane and raised in Queensland, southern New South Wales and the ACT. After first visiting Spain in 1984, he later spent long periods living in Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia.

Stegemann has worked in media, publishing and higher education, and as a Spanish-English translator, in both Australia and Spain. He was formerly the managing editor of ‘The Adelaide Review’, and the founding editor of ‘The Melbourne Review’.

Stegemann has written widely on Spanish art, history, culture and politics, and now lives and works in rural south-east Queensland. He continues to spend time each year in Spain. He has recently published The Beautiful Obscure, a remarkable work which analyses aspects of Spanish cultural influence from an Australian viewpoint.

In this conversation, Stegemann talks about synergies and divergences between both countries with past, present and future perspectives, all seen within the framework of his own love of both countries.

-In The Beautiful Obscure, the discovery and the experience of Spain from your Australian background comes together with your reflection on the historical similarities, encounters and distances between both countries. The question is obvious: what attracts an Australian to Spain, back in the 80s?

In some respects it was fortuitous. Travelling around what was then ‘western’ Europe in the year after completing my first university degree, I had not planned to spend more than a few days in the north of Spain. Yet once inside the country, I felt an immediate attraction – unlike anything I felt, for example, in Greece, or Italy, France or Germany – and a planned two-three days became one month as I travelled ever deeper into the country. And this was 1984 – a Spain that has in many respects completely disappeared now. What I felt strongest – and I discuss this in some detail in the book – was a sense of discovering a Europe I had never been told about. It was as if an entire section of the continent, whose history I thought I had studied, had been hidden.

So the attraction was to the unknown, but it was not as simple as the classic ‘orientalising’ experience of ‘the exotic’. It was clear straight away that this was part of my own cultural heritage, part of the story of the continent of my ancestors. I immediately thought, “How did I not know this?” and then, “How can I live here?” When I returned to Australia and explained my plan to return to live in Spain as soon as possible – something I had never considered until then – my family and friends had no idea what I was talking about. Spain had not yet joined the EU, and was debating its entry into NATO. Two years later, and having armed myself with a second degree – this time in education – I returned to work initially as an English teacher. So began, with life in Spain in 1987, what has become the most significant chapter and influence on my adult life.

One thing that is important for me is to emphasise that being Australian – as opposed to British or North American – I believe I bring a different perspective on Spanish history and culture. I come from ‘the south’, from the Pacific and from a European colony: all of these influence my manner of understanding Spain and its place in the world. No part of Australia was ever colonised by Spain (though it might have been), nor has Australia ever had any conflicts with Spain. In that sense, we have no ‘history’, no ‘baggage’ as companion countries. People often remark on the similarity (to some extent – it shouldn’t be exaggerated) of character between Australians and Spaniards, an open friendliness and, I must say, a reputation for having a defiant attitude to authority, which is mostly façade and not a reality! Certainly there is a determination in both countries to enjoy life, and fill it with as much pleasure as possible, albeit Australians are more socially conservative.

-For centuries, Spain’s relationship with Australia seems to have been a story of frustration: despite maintaining a presence in the Pacific, neither the ships of the imperial adventure nor those of the scientific expeditions would find permanent accommodation on its coasts. Even in diplomatic and commercial terms, not a few opportunities were lost … «Your schooling had somehow neglected Spain,», said British Ted Hughes in a poem to his wife, the also poet, but American, Sylvia Plath. Has that also been the case in Australia? Are cliches the best allies of ignorance?

In Australia, Spain has always been neglected as a subject of political and historical study. Firstly, this was due for many years to Australia’s imitation of British education with all its cultural and geopolitical prejudices; latterly because, having removed ourselves from the British imperial orbit, over the past four decades Australia has consciously positioned itself as a regional Asian power. For an ‘Anglo’ country, there is a very high level of ‘Asia literacy’ in Australia. Having said that, we stepped out from under the British umbrella to become a faithful, and somewhat subservient, ally of the Americans, whose culture has come to swamp so much of our own.

Spain is a popular tourist destination, though I despair of the number of Australians who believe that visiting Barcelona and San Sebastian constitutes ‘visiting Spain’. Time pressures weigh on tourists, of course, but so few take the opportunity to explore those regions that for me are a highlight of Spain: Madrid; the villages of Zamora, Soria and Segovia; the Maestrazgo; the hills of Jaen, the Tierra de Campos, and not forgetting the backroads of Toledo and Ciudad Real, through deepest Quixote territory…

Madrid is an interesting case in point. I’ve always been fascinated by those foreigners who dislike Madrid, and express a strong preference for Barcelona, or even Valencia or San Sebastian. For me, Madrid is such a concentration of so many historical, cultural and political lines of influence, it is indispensable as a reference point. This is why I have looked to compare moments from the history of Madrid with Australia: two examples are those navigators, returned from the Pacific, spending years begging at the court of Phillip III for funds to return to discover what they sense is still there, and never quite making it… or Carlos III and the building of the Puerta de Alcalá: it arose in the very same years as the British were planning their penal colony at the bottom of the world, and of course the death of Carlos III in 1788, the same year the British founded Port Jackson, now Sydney.

For me these are not simply coincidences; they are parallel lines that flow through history, not necessarily touching at any point, but somehow bearing an influence on each other. This is why I felt the interweaving histories of Australia and Spain was a great, untold story.

But it is also interesting to consider the Ted Hughes poem you quote. For me it is a classic example of that mid-century north-Atlantic interpretation of Spain. A black and white Spain of Franco-era clichés and orientalist essentialising, that has aged badly. This, if you’ll permit me, is the view of Spain many Australians do not have, for we do not have those centuries of cultural comparison (and at times, of condescension). You’ll have noticed that in a 435 page book about Spain, I have made no mention of football, or bullfighting, very little mention of ‘blood and death’, and only very few mentions of flamenco. This is not because I do not appreciate and enjoy the cultural uniqueness of how these things are performed in Spain (in particular, the cante jondo tradition of flamenco) but I wanted to write a book that avoided all the usual staging posts for commentary on Spain.

(Incidentally, the question of the leyenda negra: while trying to avoid the above clichés, it is undeniable, at least in my cultural and political readings, of a certain dismissive tone towards Spain that I think runs through a lot of Anglo thinking. But to say so is to invite controversy. One can believe that Spain has been poorly treated by those who came after her, and who wrote their own versions of history as the ‘cultural victors’ whose influence extends so much into our contemporary world; you can see this, and understand it, without falling into Franco-like conspiracy theories, that a worldwide masonic and communist plot was out to destroy Spain. But I’ve seen, with the recent debates around Roca Barea, that to flag up the leyenda negra as something real, can get you tagged as reactionary, as Francoist…!)

One other obvious question in writing this book: how to express a love for Spanish culture, and invite others to immerse themselves in it, without them having the access afforded by the language? (Because no matter how much we can translate, ‘love’ and ‘amor’ are not the same thing; ‘evening’ and ‘atardecer’ are not the same… they all carry the weight of their own cultural heritage, and to say one thing, is not the same as to say the other! I have recently been doing some short translations of the poetry of Miguel Hernández into English, and it is enormously difficult to convey the sense of his words… the meaning, maybe, but the sense, the feeling… almost impossible!!) This is why I have made little mention of two of the greatest aspects of Spanish culture – its literature and its popular music – as they are difficult to access properly for foreigners. For this reason, I go in depth into the world of art, as a more universal language. Apart from the obvious masters Goya and Velázquez, I wanted people to know some of my favourite painters: Zurburán, Sorolla and Zuloaga. They tell me so much about Spain, and then specifically about Catholicism, or Valencia, or Castile. I also wanted to float a few ‘controversial’ opinions: I have never really liked the art of Dalí, or much of Picasso, or Gaudí. I have always preferred Ribera to Velázquez. These are just personal tastes. Other Spanish favourites are Juan de Juanes, Pedro Orrente, Luis Morales, Alonso Cano, the nineteenth century romantics and history painters… And perhaps above them all, for me, is El Greco. Truly, the greatest.

(And how often would I visit the Prado and find a room full of people crowding around Hieronymus Bosch – which is normal – but completely ignoring that singular masterpiece, on the opposite wall, which is Patinir’s vision of Charon crossing the Styx!)

For me this concentration on what is largely, though not exclusively, religious art, is deliberate. We live in a time where the Catholic Church has suffered enormous reputational damage; in Australia this is very pronounced. I make the point in the book that to defend Catholicism is a hard sell nowadays in a secular and in many ways angry society. However there is (for someone raised Anglican like myself) a clear distinction between the Catholic Church as an institution, and Catholicism itself as a belief system which has been the driving force, or inspiration, for much of the greatest art and poetry of the last 500 or more years. It is this element of Catholicism I wish to celebrate; it is an aesthetic judgment, not a moral one.

– It is true that the first city in the world to dedicate a street to AC / DC was Spanish … but the lack of knowledge between the two countries seems to have been a shared passion: in Spain we also have our cliches about Australia.

When I first lived in Spain the ignorance of Australia was almost total – and the same was true in Australia as regards Spain. I confess in the book how, as a young boy, I thought Seville was an Italian city… In the late 80s, when I was living in Madrid, the cliché of ‘Crocodile Dundee’ took over – something which all Australians abroad had to live with for far too long! Over the years, this situation has changed dramatically, but Australia remains something of an unknown. The internet brings the whole world into view, but there are still questions about the nature of Australia: just how big is it really? Are there so many dangerous animals and insects? Is it still a British colony? How Asian is it? I think a lot of people are surprised by just how multicultural Australia is; the huge diversity of our population.

Another significant factor in overcoming this ignorance has occurred over the past decade: on the one hand, more and more young Australians make Spain an essential part of their international travels; while after the 2008 financial crisis, thousands of young Spaniards – above all highly skilled professionals – found work opportunities in Australia. This was something of a ‘brain drain’ for Spain, but Australia has benefitted enormously. Spaniards can often be found among the leading scientists and researchers in Australia today. Additionally, there are community networks of young Spanish people that simply did not exist 25 years ago.

-Australia and Spain, even at different times, faced a similar question: what to do with the native populations, already in Australia, already in Spanish America …

Yes, absolutely. But with at least two differences: firstly, in Australia this problem is still with us, despite the huge progress that has been made. In fact, many people would argue (and I would tend to agree) that the long, slow process of reconciliation with the Indigenous population remains Australia’s greatest challenge as a nation. Secondly, in Australia the Indigenous presence is not part of an ‘overseas empire’ but forms part of the daily fabric of our nation. In fact, the development of Australia, as we know it, was only made possible by the displacement of the Indigenous culture, with not just the major loss of life but also the profound cultural loss of languages and knowledge of the land and its uses.

While historical ‘what might have beens’ are of little practical use, I have always believed a Spanish colonisation of Australia, without being either better or worse, would have had different outcomes for the Indigenous population. There would have been significantly greater intermarriage, and a significantly greater effort made to record and preserve some of the approximately 200 languages that existed here prior to colonisation, the great majority of which have been lost. And of course, Spain would have colonised Australia around two centuries before the British, so European Australia would now be a country of some 400+ years, like the US, rather than around 230 years.

-The link or bilateral knowledge is surely more intense after the Civil War, in which there were Australians of both sexes. But also the art, to which you dedicate so many pages in his book, seems to have brought us closer, beyond Ted Hughes’ studies on Goya, until now “the” Australian Hispanicist…

Firstly a small correction – I think you mean Robert Hughes in this case! It is interesting – I think his book on Goya was one of his finest, while I thought his book on Barcelona was one of his weakest (partly because it was really a book about Catalan modernism, which is fine, but Barcelona is much more than that; I thought it was obvious that outside of his specialist areas of art and modernism, he didn’t really give a sense of having ‘lived’ Barcelona. In fact, it felt very much as though research assistants had done most of the work. I couldn’t smell Barcelona, or hear her breathing in this book…)

Perhaps what I’ve said in the above paragraphs about art is sufficient. I would invite Spaniards, however, to explore Australian art, which is as diverse as the country itself. While Australian art has often followed European and North American trends, it has nevertheless brought a magnificent stable of artists onto the world stage. And also, of increasing importance to many Australians, of all backgrounds, is the diverse, original and profound world of Indigenous art. It represents, as much as anything, the triumph of the survival of our Indigenous peoples, and allows the non-Indigenous person a glimpse into their representations of ceremony, law, and the origins and nature of the world.

A final comment: I’ve said this in the book, and say it also whenever I talk about the book. Having spent 35+ years immersing myself into the Spanish universe has been enriching in more ways than I can recount, but above all, there is something else that I find hard to define, but which I know is true. It has made me a better person. This is perhaps true of all of us who learn to live across two cultures and two languages: we find ourselves wiser, more tolerant and, I hope, more compassionate persons. For this, I always say, and sincerely believe, that I am in debt to the Spanish people.

¿Qué novela te gustaría ver convertida en película? / What Novel Would You Like To See Adapted To Cinema?

En Barcelona se ha dado el pistoletazo de salida a la adaptación cinematográfica de «La Catedral del Mar», del autor español Ildefonso Falcones. La historia del nacimiento de la ciudad a través de la construcción de su catedral más emblemática se verá convertida en serie, y crece la expectación entre los lectores fieles a la obra original, ante lo que puede terminar siendo «o una joya, o una birria» – la pantalla no tiene término medio, vaticinan algunos.

Otras obras destacadas de la literatura universal, en las que ciudades comparten protagonismo con sus personajes, se han visto adaptadas al cine a lo largo del siglo XX. De entre ellas nos llama la atención «Grandes esperanzas» de una de las destacadas plumas inglesas, Charles Dickens. La primera adaptación cinematográfica de «Grandes esperanzas» -de 1946- sigue cosechando críticas positivas, que consideran que el largometraje es muy fiel a la obra original, y la representación que en ella se hace de Londres, tan acertada por escrito como en pantalla.

¿Qué opinas sobre las adaptaciones cinematográficas de obras literarias? ¿Crees que es posible adaptar una novela al cine sin exponerla a una constante reinterpretación, y consecuente desfiguración? ¿Has leído alguna otra novela ambientada en Londres que te encantaría ver en la gran pantalla? Estamos deseando leer tu opinión en comentarios.

Production teams recently kicked off the recording, in Barcelona, of an adaptation of Spanish writer Ildefonso Falcones’s most renowned work: «Cathedral of the Sea». The history and birth of the coastal city, told through the building process of its most emblematic building, is to be told on-screen. Those loyal to the original piece of literature are expectant in face of what could become «either a jewel, or a complete disaster» – there is no middle ground in cinema, some assert.

Other illustrious literary works, wherein cities share centre stage with characters, have been adapted to cinema throughout the XX and XXI centuries. Among those, we would highlight «Great Expectations» by prominent English writer Charles Dickens. The positive feedback to its first adaptation to cinema -made in 1946- is overwhelming. Viewers and readers consider the feature film bears great resemblance to the novel itself, and they see London as accurately portrayed on the big screen as it is in Dicken’s written work.

What do you think about cinema adaptations of literary works? Do you believe a novel can be turned into a movie without distorting its original message? Have you read any other novels set in London which you would love to see featured on the big screen? We would love to hear your views in the comments section.