«I am enormously grateful to all at Instituto Cervantes London who conspired to get me over the finish line»

Today we chat with one of our students, Joseph McGowan, who just passed DELE C2 exam and previously achieved DELE C1. Joseph has studied Spanish at Instituto Cervantes in London for a long time and he prepared himself for this exam with our teachers. He enjoys learning Spanish every week and travelling to the beautiful Catalonian town of Sitges.

¿Why did you decide to take DELE exam?

I decided to take the DELE exam, not out of any academic, professional or administrative necessity, but simply as a personal challenge. I wanted to learn Spanish, but I knew I had to have a deadline, otherwise I’d pootle along aimlessly. Procrastination is an art form I’ve mastered, so I needed some impetus to turn the desire to learn into a reality. Also, with years of unstructured learning of French under my belt, I knew that the vague target of «I want to speak a language» can be like trying to reach the end of the rainbow: you never quite get there; there’s always a bit further to go. The feeling you can speak a language successfully comes and goes like the weather, depending on mood, physical state, subject-matter, interlocutor, etc. So I wanted an objective and solid milestone by which to measure my progress.-

How was the preparation? What was the most difficult part for you?

Without doubt, the writing was the most difficult element. I was a terrible schoolboy, never did my homework, didn’t take any further exams after my GCSEs, so once again being faced with The Demon Blank Sheet of Paper waiting to be filled was not only an academic but also a psychological barrier to break through. Fortunately I had a fantastic teacher who was extremely patient and generous with her time and effort. She offered to be my sherpa to guide me up the mountain to the exam. And that mountain certainly did seem steep, and rocky. But once I got there, it was amazing to look back and see how far I’d come.

How did the DELE preparation classes at Instituto Cervantes London help you?

As you’ll have gathered, for me the classes were indispensable. Left to my own devices, I could never have passed the C1 and C2 exams. At an advanced level, even in their native tongue, I think someone would struggle to pass a CEFR language exam without preparation. You have to know the format of the exam; for the writing, there are models of text you may not be familiar with; and learning to manage the time in the exam is essential and, at least to me, did not come naturally. My teacher carefully planned each class so there was a progression, which stopped me spending too much time on one particular element at the expense of another. She was there to remind me that you only have to be good enough to pass the exam, there’s no point in trying to exceed the requirements. Of course, perfection is the enemy of good, but it’s sometimes hard to judge alone. In the moments when my determination wobbled and I thought, «Why am I putting myself through this?», I knew I couldn’t let her down and back out now, after we’d both invested so much time and effort.

Looking back, the fact I embarked upon this journey in my 40th year probably isn’t a coincidence. At a time of taking stock of one’s life, it’s not a bad way to live out a mid-life crisis! I am enormously grateful to all at Instituto Cervantes London who conspired to get me over the finish line (twice). The journey is not over, of course — I am now working on Spanish literature with my teacher — but I am very pleased, even proud, to have put those two important milestones behind me.

If you want to take a DELE exam, you can enrol through the online shop of Instituto Cervantes London (CLIC Londres).

These are the upcoming exam sessions at Instituto Cervantes London:

- 11 September (written and oral exam), DELE for Young Learners: Levels A1 and A2/B1

Enrolment deadline 15 July - 11 September (written exam), 11/12 September (oral exam). Level A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2

Enrolment deadline 15 July - 13 November (written and oral exam), DELE for Young Learners: Levels A1 and A2/B1

Enrolment deadline 7 October - 14 November (written exam), 13/14 November (oral exam). Levels: A1, A2, B1, B2, C1, C2

Enrolment deadline 7 October

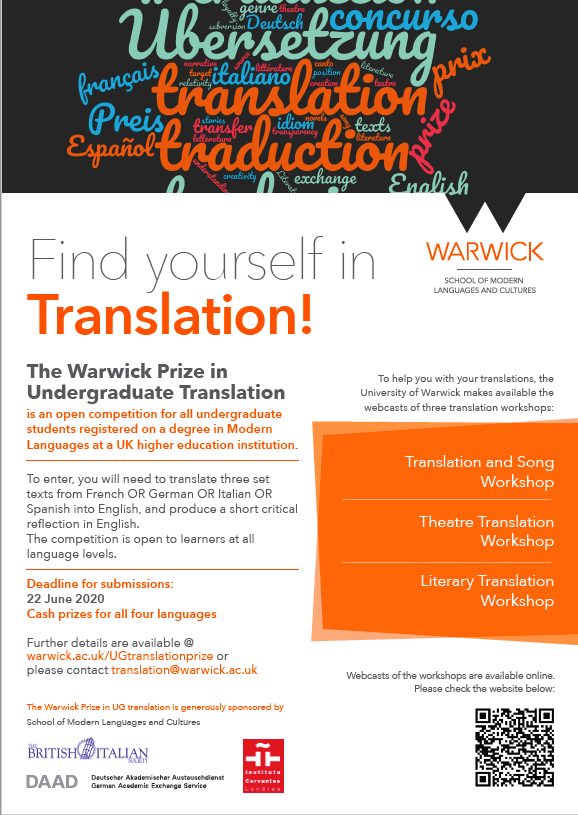

National translation competition for undergraduate students

We would like to draw your attention to a national translation competition for undergraduate students in Modern Languages in the UK, including those doing Spanish / Hispanic Studies.

The Warwick Prize in Undergraduate Translation aims to encourage students to engage with languages outside the classroom so that they can see that translation is a fun and creative activity which can be productive at all linguistic levels. See poster attached and below.

How does the Prize Work?

To enter, students will need to complete a translation portfolio. This portfolio will include:

- Translations of three set texts from EITHER French OR German OR Italian OR Spanish into English – available here.

- A critical reflection in English (300 words) on the translation approach.

- A completed entry form

To help students with their translations, the University of Warwick makes available on its website the webcasts of three translation workshops on (1) translation and song, (2) translation and theatre, and (3) translation and literature.

The set texts have been released on Thursday 7 May 2020 and entries can be submitted until 22 June 2020 at 5pm. The winners will be announced in Autumn 2020, with cash prizes for all the four languages.

Further information, including contact details and instruction for the submission of entries (via email only) can be found here.

The Warwick Prize in Undergraduate Translation is generously sponsored by the School of Modern Languages and Cultures, the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD), the British Italian Society, and the Instituto Cervantes – London.

Luke Stegemann: “En España descubrí una Europa que me habían ocultado”

Hijo de cura anglicano y criado en el corazón rural de Nueva Gales del Sur, el australiano Luke Stegemann descubrió España por sorpresa en los años 80. Enamorado del país, no tuvo más remedio que volver a vivir en él, y desde entonces compagina temporadas en Australia y temporadas en España. Con una larga carrera como profesor, traductor y periodista -The Adelaide Review, The Melbourne Review-, y popular en las redes por su afecto a todo lo español, Stegemann ha escrito dos libros de tema completa o parcialmente español: The beautiful obscure (Transmission Press, 2017) y Amnesia road: landscape, violence and memory (NewSouth Publishing, febrero 2021).

-En The Beautiful Obscure se unen su condición de australiano que descubre España y la reflexión sobre los encuentros y lejanías entre ambos países en la Historia. ¿Qué atrae a un australiano, allá por los 80, a lo español?

Tuvo algo de fortuito. Viajaba por Europa tras terminar mi primera carrera y no había planeado pasar más de unos días. Sin embargo, una vez en España, sentí una atracción inmediata, a diferencia de lo que sentía, por ejemplo, en Grecia, Italia, Francia o Alemania. Los dos o tres días que había planificado pasar allí se convirtieron en un mes a medida que viajaba cada vez más por el país. Estamos hablando de 1984, y de una España que en muchos aspectos ha desaparecido por completo. La sensación más evidente fue la de descubrir una Europa de la que nunca me habían hablado. Era como si una sección entera del continente, cuya historia creía haber estudiado, hubiera estado oculta.

Así que la atracción era hacia lo desconocido, pero no era tan simple como la experiencia clásica de «orientalización» de «lo exótico». De inmediato quedó claro que esto era parte de mi propio patrimonio cultural, parte de la historia del continente de mis antepasados. Inmediatamente pensé: «¿Cómo no supe esto?» y luego, «¿Cómo puedo vivir aquí?» Cuando regresé a Australia y expliqué mi plan para vivir en España lo antes posible, mi familia y amigos no daban crédito. España aún no se había unido a la UE y estaba discutiendo su entrada en la OTAN. Dos años después, ya estaba en España como profesor de inglés.

Una cosa importante para mí es enfatizar que al ser australiano, a diferencia de británico o norteamericano, creo que aporto una perspectiva diferente sobre la historia y la cultura española. Vengo del «sur», del Pacífico y de una colonia europea: todo esto influye en mi manera de entender España y su lugar en el mundo. Ninguna parte de Australia fue colonizada por España (aunque podría haberlo sido), ni Australia ha tenido ningún conflicto con España. En ese sentido, no tenemos «historial», ni «equipaje» como países asociados. La gente a menudo habla de la similitud (hasta cierto punto, no debería ser exagerada) de carácter entre australianos y españoles, de gente muy amistosa y, debo decir, una reputación de tener una actitud desafiante ante la autoridad, que es principalmente una fachada y no una realidad. Ciertamente, existe la determinación en ambos países de disfrutar la vida y llenarla con el mayor placer posible, aunque los australianos son más conservadores socialmente.

-Durante siglos, la relación de España con Australia parece haber sido la historia de una frustración: ni los barcos de la aventura imperial ni los de las expediciones científicas encontrarían acomodo permanente en sus costas. A la vez, ese también parece ser el caso de Australia con España: inevitable pensar en ese verso de Ted Hughes a Sylvia Plath, en el que le dice que en su escuela nunca le hablaron de España…

En Australia, España siempre ha sido descuidada como tema de estudio. Esto se debió durante muchos años a la imitación australiana de la educación británica con todos sus prejuicios culturales y geopolíticos. En las últimas cuatro décadas nos hemos alejado de la órbita imperial británica y Australia se ha posicionado conscientemente como una potencia regional de Asia. Para ser un país «anglófono», hay un nivel muy alto de «alfabetización de Asia» en Australia. Dicho esto, salimos del paraguas británico para convertirnos en un aliado fiel y algo servil de EEUU, cuya cultura ha llegado a abrumar a la nuestra.

España es un destino turístico popular, aunque me desespera la cantidad de australianos que creen que visitar Barcelona y San Sebastián constituye «visitar España». Muy pocos aprovechan la oportunidad para explorar aquellas regiones que para mí son lo más destacado: Madrid; los pueblos de Zamora, Soria y Segovia; el Maestrazgo, las colinas de Jaén, la Tierra de Campos, sin olvidar los caminos de Toledo y Ciudad Real, a través del territorio del Quijote …

Madrid es un caso interesante en este punto. Siempre me han fascinado aquellos extranjeros a los que no les gusta. Para mí, Madrid es una concentración de tantas líneas de influencia histórica, cultural y política que es indispensable como punto de referencia. Por eso he tratado de comparar en mi libro momentos de la historia de Madrid con Australia. Ahí están los navegantes que, en época de Felipe III, reclaman atención para esa tierra, sin que les hagan caso. O cómo Carlos III muere en 1788, justo cuando los británicos fundaban lo que hoy es Sidney. Para mí, estas no son simplemente coincidencias; son líneas paralelas que fluyen a través de la historia, que no necesariamente se tocan en ningún punto, pero que de alguna manera influyen entre sí. Es por eso que sentí que las historias entrelazadas de Australia y España eran una gran historia no contada.

El poema de Ted Hughes que cita usted es un ejemplo clásico de esa interpretación de España a mediados del siglo XX desde el Atlántico Norte. Una España en blanco y negro, de clichés de la época franquista y esencialismo orientalista, que ha envejecido mucho. Esto, si me lo permiten, es la opinión de España que muchos australianos no tienen, porque no tenemos esos siglos de comparación cultural (y, a veces, de condescendencia). En The beautiful obscure no he mencionado el fútbol o las corridas de toros y muy pocas menciones al flamenco. Esto no se debe a que no aprecio y disfruto la singularidad cultural de cómo se realizan estas cosas en España, sino a que quería escribir un libro que evitara los comentarios habituales de las publicaciones.

Por cierto, y a propósito de la cuestión de la leyenda negra: al tratar de evitar los clichés anteriores, es innegable, al menos en mis lecturas culturales y políticas, apreciar un cierto tono despectivo hacia España que creo que atraviesa mucho pensamiento anglófono. Pero decirlo es invitar a la controversia. Uno puede creer que España fue maltratada por quienes la siguieron y que escribieron sus propias versiones de la historia como los «vencedores culturales», cuya influencia se extiende tanto en nuestro mundo contemporáneo. Uno puede apreciar esto y lo entiendo, sin caer en las teorías de la conspiración franquista de que un complot masónico y comunista en todo el mundo estaba tratando de destruir España. Pero he visto, con los recientes debates en torno a Roca Barea, que marcar la leyenda negra como algo real, puede etiquetarte como reaccionario, como franquista, lo cual me parece absurdo.

-¿Cómo expresar un amor por la cultura española e invitar a otros a sumergirse en ella, sin que tengan el acceso que ofrece el idioma?

A veces, la literatura y la música popular pueden ser de más difícil acceso para los extranjeros. Por esta razón, en mi libro y fuera, profundizo en el mundo del arte como un lenguaje más universal. Además de maestros obvios como Goya y Velázquez, quería que la gente conociera a algunos de mis pintores favoritos: Zurbarán, Sorolla y Zuloaga. Me cuentan mucho sobre España, y luego específicamente sobre el catolicismo, o Valencia, o Castilla. También quería expresar algunas opiniones «controvertidas»: nunca me ha gustado mucho el arte de Dalí, o de Picasso, o de Gaudí. Siempre he preferido Ribera a Velázquez. Estos son solo gustos personales. Otros favoritos son Juan de Juanes, Luis Morales, Alonso Cano, los románticos del siglo XIX y los pintores de la historia … Y quizás por encima de todos ellos, para mí, está El Greco. En verdad, el más grande.

Para mí, esta concentración en lo que es en gran medida, aunque no exclusivamente, arte religioso, es deliberada. Vivimos en una época en que la Iglesia Católica ha sufrido un enorme daño de reputación; en Australia esto es muy pronunciado. Destaco en el libro que defender el catolicismo es difícil de vender hoy en una sociedad secular y en muchos sentidos enojada. Sin embargo, existe (para alguien criado en los anglicanos como yo) una clara distinción entre la Iglesia católica como institución y el catolicismo en sí mismo, como un sistema de creencias que ha sido la fuerza motriz o la inspiración de gran parte del arte y la poesía más importantes de los últimos 500 o más años. Es este elemento del catolicismo lo que deseo celebrar; es un juicio estético, no moral.

–En España también tenemos nuestros clichés sobre Australia.

Cuando viví en España por primera vez, la ignorancia de Australia era casi total, y lo mismo era cierto en Australia con respecto a España. A finales de los años 80, el cliché de ‘Crocodile Dundee’ fue algo con lo que, como todos los australianos en el extranjero, tuve que vivir mucho tiempo. Con los años, esta situación ha cambiado drásticamente, pero Australia sigue siendo algo desconocido. Internet pone a la vista todo el mundo, pero todavía hay preguntas sobre la naturaleza de Australia: ¿Cómo de grande es realmente? ¿Hay tantos animales e insectos peligrosos? ¿Sigue siendo una colonia británica? ¿Cómo es de asiático? Creo que mucha gente está sorprendida por lo multicultural que es Australia y la gran diversidad de nuestra población.

Otro factor importante para superar la ignorancia ha ocurrido en la última década: por un lado, cada vez más jóvenes australianos hacen en España una parte esencial de sus viajes internacionales; mientras que después de la crisis financiera de 2008, miles de jóvenes españoles, sobre todo profesionales altamente calificados, encontraron oportunidades de trabajo en Australia. Esto fue una especie de «fuga de cerebros» para España, pero Australia se ha beneficiado enormemente. Los españoles a menudo se encuentran entre los principales científicos e investigadores en Australia en la actualidad.

-Australia y España afrontaron una cuestión similar: qué hacer con las poblaciones originarias.

Si, absolutamente. Pero con al menos dos diferencias: en primer lugar, en Australia este problema todavía está con nosotros, a pesar del enorme progreso que se ha logrado. De hecho, muchas personas argumentarían (y yo estaría de acuerdo) que el largo y lento proceso de reconciliación con la población indígena sigue siendo el mayor desafío de Australia como nación. En segundo lugar, en Australia, la presencia indígena no forma parte de un «imperio de ultramar», sino que forma parte del tejido cotidiano de nuestra nación. De hecho, el desarrollo de Australia, tal como lo conocemos, sólo fue posible gracias al desplazamiento de la cultura indígena.

Siempre he creído que una colonización española de Australia, sin ser ni mejor ni peor, habría tenido resultados diferentes para la población indígena. Hubiera habido más matrimonios mixtos y un esfuerzo significativamente mayor para registrar y preservar algunos de los aproximadamente 200 idiomas que existían aquí antes de la colonización, la gran mayoría de los cuales se han perdido.

–El arte, al que tantas páginas dedica en su libro, parece habernos aproximado, más allá de los estudios sobre Goya de Robert Hughes, hasta ahora “el” hispanista australiano…

Es interesante: creo que su libro sobre Goya fue uno de los mejores, mientras que su libro sobre Barcelona fue uno de los más débiles: fuera de sus áreas de especialización de arte y modernismo, en realidad no daba la sensación de haber «vivido» Barcelona. En todo caso, yo invitaría a los españoles a explorar el arte australiano, que es tan diverso como el propio país. Aunque a menudo ha seguido las tendencias europeas y norteamericanas, sin embargo, también ha traído un magnífico grupo de artistas al escenario mundial. También tiene una creciente importancia para muchos australianos, de todos los orígenes, el mundo diverso, original y profundo del arte indígena.

-Cerramos. Han sido 35 años desde que se encontró con España…

Lo digo en mi libro. Tantos años sumergiéndome en el universo español han resultado enriquecedores en más formas de las que puedo contar, pero sobre todo, hay algo más que me resulta difícil de definir, aunque que sé que es cierto. Me ha hecho una mejor persona. Esto tal vez sea cierto para todos los que aprendemos a vivir en dos culturas y dos idiomas: nos hacemos personas más sabias, más tolerantes y, espero, más compasivas. Por esto, siempre digo, y lo creo sinceramente, que estoy en deuda con los españoles.

Luke Stegemann: «In Spain I discovered a Europe I had never been told about»

Luke Stegemann was born in Brisbane and raised in Queensland, southern New South Wales and the ACT. After first visiting Spain in 1984, he later spent long periods living in Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia.

Stegemann has worked in media, publishing and higher education, and as a Spanish-English translator, in both Australia and Spain. He was formerly the managing editor of ‘The Adelaide Review’, and the founding editor of ‘The Melbourne Review’.

Stegemann has written widely on Spanish art, history, culture and politics, and now lives and works in rural south-east Queensland. He continues to spend time each year in Spain. He has recently published The Beautiful Obscure, a remarkable work which analyses aspects of Spanish cultural influence from an Australian viewpoint.

In this conversation, Stegemann talks about synergies and divergences between both countries with past, present and future perspectives, all seen within the framework of his own love of both countries.

-In The Beautiful Obscure, the discovery and the experience of Spain from your Australian background comes together with your reflection on the historical similarities, encounters and distances between both countries. The question is obvious: what attracts an Australian to Spain, back in the 80s?

In some respects it was fortuitous. Travelling around what was then ‘western’ Europe in the year after completing my first university degree, I had not planned to spend more than a few days in the north of Spain. Yet once inside the country, I felt an immediate attraction – unlike anything I felt, for example, in Greece, or Italy, France or Germany – and a planned two-three days became one month as I travelled ever deeper into the country. And this was 1984 – a Spain that has in many respects completely disappeared now. What I felt strongest – and I discuss this in some detail in the book – was a sense of discovering a Europe I had never been told about. It was as if an entire section of the continent, whose history I thought I had studied, had been hidden.

So the attraction was to the unknown, but it was not as simple as the classic ‘orientalising’ experience of ‘the exotic’. It was clear straight away that this was part of my own cultural heritage, part of the story of the continent of my ancestors. I immediately thought, “How did I not know this?” and then, “How can I live here?” When I returned to Australia and explained my plan to return to live in Spain as soon as possible – something I had never considered until then – my family and friends had no idea what I was talking about. Spain had not yet joined the EU, and was debating its entry into NATO. Two years later, and having armed myself with a second degree – this time in education – I returned to work initially as an English teacher. So began, with life in Spain in 1987, what has become the most significant chapter and influence on my adult life.

One thing that is important for me is to emphasise that being Australian – as opposed to British or North American – I believe I bring a different perspective on Spanish history and culture. I come from ‘the south’, from the Pacific and from a European colony: all of these influence my manner of understanding Spain and its place in the world. No part of Australia was ever colonised by Spain (though it might have been), nor has Australia ever had any conflicts with Spain. In that sense, we have no ‘history’, no ‘baggage’ as companion countries. People often remark on the similarity (to some extent – it shouldn’t be exaggerated) of character between Australians and Spaniards, an open friendliness and, I must say, a reputation for having a defiant attitude to authority, which is mostly façade and not a reality! Certainly there is a determination in both countries to enjoy life, and fill it with as much pleasure as possible, albeit Australians are more socially conservative.

-For centuries, Spain’s relationship with Australia seems to have been a story of frustration: despite maintaining a presence in the Pacific, neither the ships of the imperial adventure nor those of the scientific expeditions would find permanent accommodation on its coasts. Even in diplomatic and commercial terms, not a few opportunities were lost … «Your schooling had somehow neglected Spain,», said British Ted Hughes in a poem to his wife, the also poet, but American, Sylvia Plath. Has that also been the case in Australia? Are cliches the best allies of ignorance?

In Australia, Spain has always been neglected as a subject of political and historical study. Firstly, this was due for many years to Australia’s imitation of British education with all its cultural and geopolitical prejudices; latterly because, having removed ourselves from the British imperial orbit, over the past four decades Australia has consciously positioned itself as a regional Asian power. For an ‘Anglo’ country, there is a very high level of ‘Asia literacy’ in Australia. Having said that, we stepped out from under the British umbrella to become a faithful, and somewhat subservient, ally of the Americans, whose culture has come to swamp so much of our own.

Spain is a popular tourist destination, though I despair of the number of Australians who believe that visiting Barcelona and San Sebastian constitutes ‘visiting Spain’. Time pressures weigh on tourists, of course, but so few take the opportunity to explore those regions that for me are a highlight of Spain: Madrid; the villages of Zamora, Soria and Segovia; the Maestrazgo; the hills of Jaen, the Tierra de Campos, and not forgetting the backroads of Toledo and Ciudad Real, through deepest Quixote territory…

Madrid is an interesting case in point. I’ve always been fascinated by those foreigners who dislike Madrid, and express a strong preference for Barcelona, or even Valencia or San Sebastian. For me, Madrid is such a concentration of so many historical, cultural and political lines of influence, it is indispensable as a reference point. This is why I have looked to compare moments from the history of Madrid with Australia: two examples are those navigators, returned from the Pacific, spending years begging at the court of Phillip III for funds to return to discover what they sense is still there, and never quite making it… or Carlos III and the building of the Puerta de Alcalá: it arose in the very same years as the British were planning their penal colony at the bottom of the world, and of course the death of Carlos III in 1788, the same year the British founded Port Jackson, now Sydney.

For me these are not simply coincidences; they are parallel lines that flow through history, not necessarily touching at any point, but somehow bearing an influence on each other. This is why I felt the interweaving histories of Australia and Spain was a great, untold story.

But it is also interesting to consider the Ted Hughes poem you quote. For me it is a classic example of that mid-century north-Atlantic interpretation of Spain. A black and white Spain of Franco-era clichés and orientalist essentialising, that has aged badly. This, if you’ll permit me, is the view of Spain many Australians do not have, for we do not have those centuries of cultural comparison (and at times, of condescension). You’ll have noticed that in a 435 page book about Spain, I have made no mention of football, or bullfighting, very little mention of ‘blood and death’, and only very few mentions of flamenco. This is not because I do not appreciate and enjoy the cultural uniqueness of how these things are performed in Spain (in particular, the cante jondo tradition of flamenco) but I wanted to write a book that avoided all the usual staging posts for commentary on Spain.

(Incidentally, the question of the leyenda negra: while trying to avoid the above clichés, it is undeniable, at least in my cultural and political readings, of a certain dismissive tone towards Spain that I think runs through a lot of Anglo thinking. But to say so is to invite controversy. One can believe that Spain has been poorly treated by those who came after her, and who wrote their own versions of history as the ‘cultural victors’ whose influence extends so much into our contemporary world; you can see this, and understand it, without falling into Franco-like conspiracy theories, that a worldwide masonic and communist plot was out to destroy Spain. But I’ve seen, with the recent debates around Roca Barea, that to flag up the leyenda negra as something real, can get you tagged as reactionary, as Francoist…!)

One other obvious question in writing this book: how to express a love for Spanish culture, and invite others to immerse themselves in it, without them having the access afforded by the language? (Because no matter how much we can translate, ‘love’ and ‘amor’ are not the same thing; ‘evening’ and ‘atardecer’ are not the same… they all carry the weight of their own cultural heritage, and to say one thing, is not the same as to say the other! I have recently been doing some short translations of the poetry of Miguel Hernández into English, and it is enormously difficult to convey the sense of his words… the meaning, maybe, but the sense, the feeling… almost impossible!!) This is why I have made little mention of two of the greatest aspects of Spanish culture – its literature and its popular music – as they are difficult to access properly for foreigners. For this reason, I go in depth into the world of art, as a more universal language. Apart from the obvious masters Goya and Velázquez, I wanted people to know some of my favourite painters: Zurburán, Sorolla and Zuloaga. They tell me so much about Spain, and then specifically about Catholicism, or Valencia, or Castile. I also wanted to float a few ‘controversial’ opinions: I have never really liked the art of Dalí, or much of Picasso, or Gaudí. I have always preferred Ribera to Velázquez. These are just personal tastes. Other Spanish favourites are Juan de Juanes, Pedro Orrente, Luis Morales, Alonso Cano, the nineteenth century romantics and history painters… And perhaps above them all, for me, is El Greco. Truly, the greatest.

(And how often would I visit the Prado and find a room full of people crowding around Hieronymus Bosch – which is normal – but completely ignoring that singular masterpiece, on the opposite wall, which is Patinir’s vision of Charon crossing the Styx!)

For me this concentration on what is largely, though not exclusively, religious art, is deliberate. We live in a time where the Catholic Church has suffered enormous reputational damage; in Australia this is very pronounced. I make the point in the book that to defend Catholicism is a hard sell nowadays in a secular and in many ways angry society. However there is (for someone raised Anglican like myself) a clear distinction between the Catholic Church as an institution, and Catholicism itself as a belief system which has been the driving force, or inspiration, for much of the greatest art and poetry of the last 500 or more years. It is this element of Catholicism I wish to celebrate; it is an aesthetic judgment, not a moral one.

– It is true that the first city in the world to dedicate a street to AC / DC was Spanish … but the lack of knowledge between the two countries seems to have been a shared passion: in Spain we also have our cliches about Australia.

When I first lived in Spain the ignorance of Australia was almost total – and the same was true in Australia as regards Spain. I confess in the book how, as a young boy, I thought Seville was an Italian city… In the late 80s, when I was living in Madrid, the cliché of ‘Crocodile Dundee’ took over – something which all Australians abroad had to live with for far too long! Over the years, this situation has changed dramatically, but Australia remains something of an unknown. The internet brings the whole world into view, but there are still questions about the nature of Australia: just how big is it really? Are there so many dangerous animals and insects? Is it still a British colony? How Asian is it? I think a lot of people are surprised by just how multicultural Australia is; the huge diversity of our population.

Another significant factor in overcoming this ignorance has occurred over the past decade: on the one hand, more and more young Australians make Spain an essential part of their international travels; while after the 2008 financial crisis, thousands of young Spaniards – above all highly skilled professionals – found work opportunities in Australia. This was something of a ‘brain drain’ for Spain, but Australia has benefitted enormously. Spaniards can often be found among the leading scientists and researchers in Australia today. Additionally, there are community networks of young Spanish people that simply did not exist 25 years ago.

-Australia and Spain, even at different times, faced a similar question: what to do with the native populations, already in Australia, already in Spanish America …

Yes, absolutely. But with at least two differences: firstly, in Australia this problem is still with us, despite the huge progress that has been made. In fact, many people would argue (and I would tend to agree) that the long, slow process of reconciliation with the Indigenous population remains Australia’s greatest challenge as a nation. Secondly, in Australia the Indigenous presence is not part of an ‘overseas empire’ but forms part of the daily fabric of our nation. In fact, the development of Australia, as we know it, was only made possible by the displacement of the Indigenous culture, with not just the major loss of life but also the profound cultural loss of languages and knowledge of the land and its uses.

While historical ‘what might have beens’ are of little practical use, I have always believed a Spanish colonisation of Australia, without being either better or worse, would have had different outcomes for the Indigenous population. There would have been significantly greater intermarriage, and a significantly greater effort made to record and preserve some of the approximately 200 languages that existed here prior to colonisation, the great majority of which have been lost. And of course, Spain would have colonised Australia around two centuries before the British, so European Australia would now be a country of some 400+ years, like the US, rather than around 230 years.

-The link or bilateral knowledge is surely more intense after the Civil War, in which there were Australians of both sexes. But also the art, to which you dedicate so many pages in his book, seems to have brought us closer, beyond Ted Hughes’ studies on Goya, until now “the” Australian Hispanicist…

Firstly a small correction – I think you mean Robert Hughes in this case! It is interesting – I think his book on Goya was one of his finest, while I thought his book on Barcelona was one of his weakest (partly because it was really a book about Catalan modernism, which is fine, but Barcelona is much more than that; I thought it was obvious that outside of his specialist areas of art and modernism, he didn’t really give a sense of having ‘lived’ Barcelona. In fact, it felt very much as though research assistants had done most of the work. I couldn’t smell Barcelona, or hear her breathing in this book…)

Perhaps what I’ve said in the above paragraphs about art is sufficient. I would invite Spaniards, however, to explore Australian art, which is as diverse as the country itself. While Australian art has often followed European and North American trends, it has nevertheless brought a magnificent stable of artists onto the world stage. And also, of increasing importance to many Australians, of all backgrounds, is the diverse, original and profound world of Indigenous art. It represents, as much as anything, the triumph of the survival of our Indigenous peoples, and allows the non-Indigenous person a glimpse into their representations of ceremony, law, and the origins and nature of the world.

A final comment: I’ve said this in the book, and say it also whenever I talk about the book. Having spent 35+ years immersing myself into the Spanish universe has been enriching in more ways than I can recount, but above all, there is something else that I find hard to define, but which I know is true. It has made me a better person. This is perhaps true of all of us who learn to live across two cultures and two languages: we find ourselves wiser, more tolerant and, I hope, more compassionate persons. For this, I always say, and sincerely believe, that I am in debt to the Spanish people.

“By the age of 14 I had travelled the breadth of Spain from Santander to Jerez”

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our sixth guest, Tim Willcox, is a famous British journalist and Chief Presenter for BBC World News.

Willcox is probably one of the most recognisable presenters on BBC and is a regular face covering some of the major international events. He has anchored live on air include the death of Slobodan Milosevic, Kashmir earthquake, July 7 bombings, Boxing Day Tsunami and Beslan school siege. He is probably most recognisable for presenting the BBC’s live coverage from Chile during events surrounding the Copiapó mining accident and anchoring the BBC’s live daytime coverage during the early days of the Cairo January 2011 Egyptian revolution.

Willcox read Spanish at Durham University and is a passionate Hispanophile who has travelled widely in Spain and South America. He says to those who would like to learn it: «Do! Go for it. Fantastic people, food and culture!»

– How is life in the newsroom under the current global pandemic?

The BBC studios are at New Broadcasting House, Langham Place W1A 1AA (as in the hideously accurate comedy series of the same name). With 6 TV studios , 36 radio studios, 60 Edit and Graphics suites it is the largest broadcast centre in the world, and the biggest newsroom in Europe. Usually it is heaving with journalists and producers, cramming the meeting rooms, canteens and communal areas, and queueing for the big glass lifts that shoot between floors. Since lockdown the newsroom is practically empty, and run by a skeleton staff. Social distancing tape stripes the floor, and areas are blocked off as if one were working in a gigantic urban maze. Staircases are now designated Up or Down, and only one person is allowed to use the lifts. Many people are now working from home – less easy if you’re presenting TV bulletins. Everything has changed on that front as well. Presenters now do their own make-up, the studio cameras are automated, and guests are interviewed ‘down the line’ by Skype or Facetime. The brave new world.

– Most of us watched your live coverage of the rescue of the Chilean miners. How do you remember that coverage?

Vividly. Even 10 years later. And for many reasons. I wasn’t the first choice to go. I got a rushed call from my Editor while having a lunchtime swim in London. Did I speak Spanish? Could I get the next flight to Chile – another presenter had pulled out – to cover what was shaping up to be an extraordinary race against time? My producer and I landed in Santiago the next day to discover that our satellite dish and other key equipment had been diverted to Buenos Aires. So we took the connecting flight to Copiapo – with no luggage except a small camera. On board I noticed an empty seat by the Chilean Mining Minister Laurence Golborne and grabbed it. He was the man in charge of the rescue operation and was to become the most popular politician in Chile.

When we arrived at the San Jose Copper and Gold mine it was dawn in a heavy Camanchaca (freezing mist). A few tents containing some shivering relations of some of the miners were huddled near the mine’s entrance. Fires were being lit, and tea boiled. We were some of the first journalists there. Over the days and weeks we chatted and filmed – sometimes in my broken Spanish (which often caused guffaws of laughter when I used a word in Castellano that had a much saltier meaning in Chilean slang.) These families, wives and girlfriends grew to trust us, and told their remarkable stories. As did the rescue drilling teams and the politicians. There was no certainty that all the miners would survive. They and we knew that. There was constant fear that at any moment some or all of the men might die.

This huddle of tents and people grew voraciously into Camp Hope with its own canteen and school. The San Jose mine and the small town of Copiapo was to be their and our home for many weeks.

Within a fortnight the world’s media had descended. Car parks for hundreds of press mobile homes were bulldozed out of the rock. The Chilean authorities had erected large screens to show the whole rescue operation involving the tiny Fenix rescue capsule that would winch them 700 metres to safety. It started just before midnight and the most moving moment for me was watching the first man out Florencio Avalos. His young son was standing with his mother near President Pinera. As the Fenix capsule broke the surface, he wept and howled with emotion as he caught sight of his father for the first time in 69 days. Everyone cried that day – even journalists going live on air.

– Which other coverage has been important for you?

Every story has been important for numerous reasons. Rwanda for the sheer barbarity and horror of what had happened combined with the stoicism of its people. The Palestinian Intifada for the palpable rage in the West Bank and Gaza. The death of Diana for the sense of national and international shock that consumed so many millions of us at the time. Cities like Baghdad I remember for the internally bombed out buildings still standing like the cardboard tubes of used fireworks, and New York obviously for 9/11. These stories, like the Arab Spring coverage in Egypt and Libya, and the revolution in Ukraine, the tsunami in Japan and typhoons in the Philippines, plus all the hideous terror attacks around the world are also seared into my memory for the sense of physical exhaustion associated with live TV coverage. There aren’t many hotels still standing after natural disasters.

– You studied Spanish at University and became fluent. How was the learning process? Who were your Professors?

Fluent? Ojala…My love of Spain began at school and an inspirational teacher who arranged cultural / hedonistic trips. By the age of 14 I had run in the San Fermin bull festival, and travelled the breadth of Spain from Santander to Jerez. I had also listened to a lot of Albeniz, Falla and Granados. My favourite book at the time was Laurie Lee’s As I Walked Out One Midsummer Morning about his journey through Spain. In my year off between school and university I retraced his journey, busking with my trumpet, and walking and hitching my way from north to south. Laurie Lee ended up near Algeciras. I completed my journey in Jerez de la Frontera where I found a temporary job as a guide at Sandeman Bodegas. At Durham university I was not a diligent student – for which I still feel shame – but I did put on productions, including Lorca’s Yerma in Spanish, and somehow get a degree. Largely thanks to the brilliant and charismatic teaching of Professor MacPherson, and Drs Dan Rodgers, Suso Ruiz and Chris Perriam who gave me a passion for Golden Age drama.

– How important is being fluent in Spanish for your journalism?

As explained it is hardly fluent. But it is useful to be able to communicate with people in their own language, and to understand their culture and national identity. It allows me to share and hopefully relate to the viewers what the characters in the story are really feeling about the events they are caught up in.

– Can you share a memory of your last news coverage in Spain?

The last story I covered in Spain was the general election. But I had been going backwards and forwards before that to Barcelona to cover the Catalan crisis. My vivid memory of that time were the huge rallies taking over the city and the drama of the declaration of independence. Sometimes we rented the large roof terrace of a stunning apartment on the Passeig de Gracia to get the best panoramic live position. Guests – both pro and anti independence were brought up to me to be interviewed. And the debates continued long after we came off air – as each side refused to change their positions.

– What would you say to someone who is thinking about learning Spanish?

Do. Go for it. Fantastic people, food and culture. And a language spoken all over the world which often opens doors. I remember meeting the Spanish Ambassador in Baghdad and after chatting away in Castellano was invited to lunch. He had the only supply of La Ina in Iraq.

– What are your favourite Spanish dishes and restaurants?

I’m basically an omnivore.

In Madrid the wonderful Ordago Restaurant near Las Ventas, also LaKasa (brilliant) and Carlos Tertiere for the best tapas and service.

In Segovia cochinillo of course at Jose Maria. Cordero asado in Pedraza always with Pedro at El Soportal.

In Barcelona – Can Colleretes. In Cadaques Compartir – for frogs legs and apple sauce. Jerez – La Tasa and Bar Juanito.

In London – it has to be Javier’s Hispania. Everything you can dream of and more….

Instituto Cervantes in London celebrates World Book Day with the reading of ‘10 Poems of Love and A Confined Song’

Instituto Cervantes in London joins the World Book Day celebrations with a reading of ’10 Poems of Love and A Confined Song’ by founder and Artistic Director of the Cervantes Theatre, Jorge de Juan. He will be joined by singer María de Juan and the event joins the list of celebrations for the 2020 Cervantine Week. It will be a week of multiple online initiatives based on all aspects of culture from books, libraries and bookstores to the publishing world, and it is open to everyone to join in and celebrate.

Having just released their new album ‘24/7’, Jorge de Juan and María de Juan come together tonight from their current locations of London and Granada, respectively. Jorge will read poems by Alfonsina Storni, Pablo Neruda, Carmen Conde, Joan Margarit and Luis García Montero among others, whilst María will sing a poem by Mario Benedetti accompanied (from Seville), by Andrés Barrios – pianist and composer who fuses world music in combination, such as flamenco and jazz. In addition, the video transmission will include photos of the journalist Jorge Pastor Sánchez, taken in Granada under the state of alarm in March 2020. The Cervantes Theatre, in collaboration with the Instituto Cervantes in London, hosts this soirée as a message of love and unity during this global pandemic.

The director of Instituto Cervantes in London, Ignacio Peyró, underlined the importance of celebrating World Book Day and Sant Jordi: “Normally on a day like today, we would be giving roses and books at our centre and celebrating reading, literature and ‘The Quixote’. This year is different, but we have made an extraordinary effort so that, although they are not face-to-face and even though they are more modest this year, our cultural activities continue to have variety and quality. In other words, they offer new, relevant and curated content by us”.

2020 Cervantine Week

Instituto Cervantes offers multiple cultural initiatives open to the public in the framework of the celebration of World Book Day, today April 23rd. With meetings with writers such as Lorenzo Silva, Elvira Lindo and Isabel Coixet, free audiobooks, the opinions and talks of more than 70 outstanding professionals in the world of culture and readings of passages from ‘Don Quixote’, among others.

The range of online projects offered today is epitomised by the verse title of the 2019 Cervantes Award winner, Joan Margarit: ‘Freedom is a bookstore’. The Cervantine Week aims to bring home, at this stage of confinement, the best of our book culture as well as promote reading and the celebration of authors, publishers and booksellers.

Even though the Instituto Cervantes in London was forced to close in response to the British government guidelines on COVID-19, our mission and cultural programmes continue online.

The Best Spanish Short Films with CinemaAttic

Every Monday, CinemaAttic and Instituto Cervantes in London, Manchester and Leeds share a weekly programme of ‘Seven Essential Short Films of the Last Decade of Spanish Cinema’. The whole thing is entirely free and accessible with English subtitles. The program is available until Sunday on both the CinemaAttic website and the Facebook event where you can also vote for your favourite shorts and comment. In addition, every Sunday at 1pm, we end the week together with ‘A Vermouth with CinemaAttic’: an online event on Facebook where a selection of the short films’ directors are interviewed.

Visual Arts: Amalgama 2020 Program

Amalgama is the first cultural initiative dedicated to promoting the work of Ibero-American female artists in the United Kingdom and will run from April to June. Amalgama, in collaboration with Instituto Cervantes in London, proposes a series of videos to present its 2020-2021 programme.

Amalgama aims to strengthen the relationship between the British public and the international art scene regarding the work of female artists from Latin America, Spain and Portugal. This year’s programme will include two exhibitions (a group show and a solo exhibition) displaying the artists’ research on the tension between nature and culture in the digital age.

The exhibitions include 15 artists, ranging from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Spain, Portugal and Venezuela. Each artist included in the final product was specially selected from the 190 applicants in an open call. For the second show, Amalgama will present the work of renowned Colombian artist Maria Elvira Escallon who was nominated for the Luis Caballero Prize in 2019.

Spanish Cinema Snippets with Joana Granero

Also available are a series of short introductions to Spanish cinema. They include presentations across a wide array of subjects, hosted by Joana Granero, Director and Founder of the London Spanish Film Festival. Each one focuses on a specific new or archival film on the work and career of leading names in Spanish cinema as well as artistic movements and schools.

In session one, Granero talks about José Luis Cuerda; filmmaker, screenwriter and producer. In session two, she will talk about a successful case: ESCAC. ESCAC, Escola Superior de Cinema i Audiovisuals de Catalunya, where teamwork and crossing barriers are primary guidelines. They have produced some of the most interesting and fresh productions over the last few years.

Literary podcasts with The Eye of Hispanic American Culture

April’s literary podcasts are produced by The Eye of Hispanic American Culture and led by Enrique Záttara who is responsible for the project. They include central figures such as the Spanish poet, professor and director of Instituto Cervantes, Luis García Montero and the Argentine novelist Mariana Enríquez.

The Eye of Hispanic American Culture is a multimedia, international and bilingual cultural project, based in London. Its objective is to promote the Hispanic-American culture residing in Europe and across the globe by connecting and informing artists, writers and intellectuals.

Great Spanish and Ibero-American composers season

Additionally, the Iberian & Latin American Music Society (ILAMS) and Instituto Cervantes in London present a series of podcasts which bring the life and work of the most representative Spanish and Ibero-American composers to life. The podcasts are released on a monthly basis and celebrate the rich musical tradition of our countries.

Ray Picot, concert reviewer at ILAMS and writer of a popular monthly column for Echoes Magazine, will focus on the masterpieces of Enrique Granados, who was one of a triumvirate of great Spanish composers to achieve international acclaim during the early 20th century.

El Instituto Cervantes de Londres celebra el Día del Libro con la lectura de ‘10 poemas de amor y una canción confinada’

El Instituto Cervantes de Londres se suma a las celebraciones del Día Internacional del Libro con una lectura de ‘10 Poemas de amor y una canción confinada’, a cargo del fundador y Director Artístico del Cervantes Theatre, Jorge de Juan, y la cantante María de Juan, que se engloban dentro de La Semana Cervantina 2020, con numerosas iniciativas culturales por internet relacionadas con el libro, las bibliotecas, las librerías y el mundo editorial, abiertas a la participación de todos.

Jorge de Juan y María de Juan, que acaba de publicar su disco 24/7, se unen en la distancia, desde Londres y Granada, respectivamente; él leyendo poemas de Alfonsina Storni, Pablo Neruda, Carmen Conde, Joan Margarit y Luis García Montero, entre otros, y ella cantando un poema de Mario Benedetti acompañada desde Sevilla, por Andrés Barrios, pianista y compositor que fusiona músicas del mundo, como el flamenco y el jazz. Además, el vídeo incluye fotos cedidas por el periodista Jorge Pastor Sánchez, tomadas en Granada bajo el estado de alarma, en marzo de 2020. Es una velada propuesta por el Cervantes Theatre de Londres, en colaboración con el Instituto Cervantes Londres, un mensaje de amor en los tiempos del virus.

El director del Instituto Cervantes de Londres, Ignacio Peyró, destacó la importancia de la celebración del Día del Libro y de Sant Jordi: “Normalmente un día como hoy estaríamos repartiendo rosas y libros en el centro y celebrando la lectura, la literatura y ‘El Quijote’. Este año es distinto, pero hemos hecho un esfuerzo extraordinario, para que, aunque no sean presenciales y aunque sean más modestas, nuestras actividades culturales sigan teniendo variedad y calidad. Es decir, que ofrezcan contenidos novedosos, relevantes y curados por nosotros mismos”.

Semana Cervantina 2020

El Instituto Cervantes ofrece múltiples iniciativas culturales abiertas a la participación en el marco de la celebración del Día Internacional del Libro, hoy 23 de abril, con encuentros con escritores como Lorenzo Silva, Elvira Lindo e Isabel Coixet, audiolibros gratuitos, opiniones de más de 70 profesionales destacados de la cultura y lecturas de pasajes del Quijote, entre otros.

Este abanico de proyectos en línea en el marco del Día Internacional del Libro y englobados bajo el lema general La libertad es una librería, título de un verso del último premio Cervantes, Joan Margarit. La Semana Cervantina pretende acercar a los hogares, en esta etapa de confinamiento, la mejor cultura del libro, contribuir al fomento de la lectura y promocionar a autores, editores y libreros.

Desde el cierre del Instituto Cervantes de Londres, en respuesta a la alerta sanitaria provocada por el coronavirus COVID-19 y siguiendo las directrices de las autoridades británicas y españolas, el programa cultural del centro ha pasado a ser en línea.

Los mejores cortometrajes con CinemaAttic

Cada lunes, CinemaAttic y los Institutos Cervantes de Londres, Mánchester y Leeds comparten un programa semanal con ‘Siete Cortometrajes Básicos de la Historia Moderna del Cine Español’, en abierto y con subtítulos en inglés. El programa está disponible hasta el domingo en la web de CinemaAttic y en el evento de Facebook donde también se puede votar por vuestros cortos favoritos y comentar de manera interactiva. ️Además, todos los domingos a la 1pm, terminamos la semana juntos con ‘Un Vermut con CinemaAttic’, evento online en Facebook donde se entrevistará a algunos de los directores de las películas.

Artes Visuales: Programa Amalgama 2020

A lo largo de los meses de abril, mayo y junio, Amalgama, la primera iniciativa cultural dedicada a promover el trabajo de mujeres artistas iberoamericanas en el Reino Unido, con la colaboración del Instituto Cervantes de Londres, propone un ciclo de vídeos de presentación del programa Amalgama 2020-2021.

El programa de Amalgama tiene como objetivo fortalecer la relación del público británico y la escena artística internacional por el trabajo de mujeres artistas de América Latina, España y Portugal. El programa de este año comprenderá dos exposiciones, una colectiva y otra individual, en las que las artistas analizarán la tensión entre la naturaleza, la cultura y los cuerpos en la era digital.

La exposición colectiva contará con el trabajo de 15 artistas de Argentina, Brasil, Chile, Colombia, España, Portugal y Venezuela, seleccionadas de las 190 candidaturas recibidas en esta primera convocatoria. La exposición individual estará dedicada a la obra de la reconocida artista colombiana María Elvira Escalón, recientemente seleccionada para el prestigioso premio Luis Caballero, en Colombia.

Píldoras de cine español con Joana Granero

A lo largo de los meses de abril, mayo y junio, en jueves alternos, el Instituto Cervantes de Londres publicará vídeo presentaciones a cargo de Joana Granero, directora del Festival de Cine Español de Londres. Cada una de ellas se centra en contenidos relativos a películas recientes y de archivo, en la obra y trayectoria profesional de destacados nombres del cine español, movimientos artísticos y escuelas.

En la primera sesión se recordará la figura de José Luis Cuerda, quien fue más que un director de cine, un guionista y un productor. Por su parte, en la segunda sesión se tratará un caso de éxito: ESCAC. La escuela de cine de Barcelona, además de ofrecer cursos con un lado práctico importante, ha producido algunas de las películas españolas recientes más interesantes.

Podcasts literarios con El Ojo de la Cultura Hispanoamericana

Los podcasts literarios del mes de abril, producidos por El Ojo de la Cultura Hispanoamericana, tienen como figuras centrales al poeta español, catedrático y director del Instituto Cervantes, Luis García Montero y a la novelista argentina Mariana Enríquez, conducidos por Enrique Záttara, responsable del proyecto.

El Ojo de la Cultura Hispanoamericana es un proyecto cultural multimedia, internacional y bilingüe, con base en Londres. Su objetivo es dar a conocer, difundir y conectar entre sí a los artistas, escritores, intelectuales y promotores de cultura de origen hispanoamericano residentes en Europa y el mundo.

Ciclo Grandes compositores españoles e iberoamericanos

Además, la Sociedad de Música Ibérica y Latinoamericana (ILAMS) y el Instituto Cervantes de Londres presentan un ciclo de podcasts que, a modo de guía de audición, y con periodicidad mensual, acercan la vida y obra de alguno de los compositores españoles e iberoamericanos más representativos de la tradición musical de nuestros países.

Ray Picot, crítico de conciertos en la Sociedad de Música Ibérica y Latinoamericana (ILAMS) desde 2001 y escritor de una columna mensual en la revista Echoes, resaltará las obras maestras clave de Enrique Granados, uno de los grandes compositores españoles, que alcanzó el reconocimiento internacional durante los primeros años del siglo XX.

“There’s much talent in Spanish film industry and now it’s being channeled”

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our fifth guest, Joana Granero, is the director of the London Spanish Film Festival in London.

Granero was born in Tarragona (Catalonia). After graduating in Law from the University of Barcelona she spent a couple of years in Italy and then moved to London, where she worked in publishing and got a MSc in Political and Social Theory from Birkbeck College.

Out of a passion for cinema Granero created the London Spanish Film Festival in 2005, an event that was to fill a gap in London’s cultural panorama by bringing contemporary Spanish cinema in a well-defined context.

In 2008 the Ambassador of Spain in London awarded her with the civil merit medal (Orden de Isabel la Católica) in recognition of her work with Spanish cinema. Granero also works as an independent curator and producer.

– Out of a passion for cinema, you created the London Spanish Film Festival in 2005, how did the idea come up?

The idea came up seeing the few opportunities to watch Spanish cinema in the UK, particularly in London, a city so rich culturally, where it was possible to watch such a wide variety of films, from so many different countries. Spain was underrepresented. Then it was only possible to watch a few films at the international festivals and only Almodóvar, Amenábar and Medem got distribution of their films with few exceptions. I thought there was so much more to watch and, having always been a cinephile, I missed it. Hence at the moment in my career in which I was looking for a change, I put myself to work and here we are!

– How have these 15 years at the LSFF been?

All in all, they’ve been exciting and enriching. They’ve been exciting because it’s never been boring or plain. We’ve lived many challenges, stressful situations alternated with moments of jubilation seeing the happiness of an audience, moments of joy with a full house and an impressed guest from Spain. Also some embarrassing and uncomfortable situations, like having to announce a guest’s last minute cancellation to an expectant audience. But every year we feel enriched with all the films, their contexts and conversations with guests, following the work of young and not so young filmmakers, and we feel extremely happy and proud to share it with audiences.

– Could you share with us a couple of anecdotes that you remember from all these years?

One of my favourite moments ever is when Jorge Coira came to present his film «18 comidas«. We introduced it briefly to a full or nearly full house, which was surprising because he was not one of the best-known directors. We went for dinner while the audience watched the film and came back to do the Q&A and as people were leaving the cinema so many were approaching him to thank him for the film and tell him how much they had enjoyed it. In English, in Spanish and in Galician. Some were even thanking me for having brought the film over. Coira was moved. I was moved and trying not to cry. It was magical. That feeling of having gifted something that had made people happy even if only for an evening.

There have been many great moments behind the scenes too, like having very informal drinks at the end of the evening in the salons of the cinema with Fernando Trueba or Javier Cámara, the Festival’s team and the projectionist. Also some delightful surprise, like when Geraldine Chaplin was our guest and a gorgeous Oona Chaplin came looking for her mother, when Olga Kurylenko came to see her friend Jordi Mollà, who was our guest, or when we spotted among our audience Mike Lee, Steve Buscemi or Elle Macpherson.

© PopKlik

– How do you describe the general picture of Spanish cinema in the UK? Do you think our film industry is in good shape?

Since we started, the position of Spanish cinema in the UK has improved generally because there have been more films distributed and home cinema and streaming have contributed to this but there is still much room for improvement. Nevertheless we are very happy to see that the Festival and its Spring Weekend have become a regular, solid and anticipated window to the cinema from Spain in London.

As per the health of our film industry, I think more should be done in terms of promotion and distribution but of one thing we are convinced: there’s much talent in Spain and it’s being channeled.

© PopKlik

– You are now working on the round off the 16th edition of the festival, what do you plan on showcasing?

It’s difficult to say anything about the next edition due to all the uncertainty surrounding COVID19 and public gatherings. We keep working in a program but we’ll have to see what is possible and what is not. So far our 10th Spring Weekend scheduled for May has had to be cancelled but we may be able to have a short «summer weekend». We have to wait a bit and see. But we keep working with the cinemas and our supporters towards a solution.

– The audience loves your Q&A featuring very diverse guests in the programme. Who would you like to have in the next upcoming months?

Hard to say without a program in hand but we’ve recently watched the latest film by Alejandro Amenabar, Mientras dure la guerra / While at War, and we’d very much like having him with us to talk about this film and his work as filmmaker but also about his music work. We’d love to have back Carlos Saura but this time with his daughter, Anna Saura, who has been producing his latest theater and film productions. I first met her when she was 9 years old and she’s become a great and determined producer. We’d also love having back Alvaro Longoria to talk about his tireless work as a director and producer.

Dream guest would be Pedro Almodovar. We’ve featured some of his work along the years and we’d love having him with us to talk about anything. He has so much to offer. We’d also like to talk cinema with Alberto Rodriguez. And books, films and food with Isabel Coixet. I could go on for a good while….

– Could you suggest the title of 5 Spanish films to our audience so they can get a good introduction to Spanish cinema?

As I’ve mentioned Pedro Almodovar, I’d start with Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown. I think there’s a before and an after that film. At the time it came out I could not get tired of watching it. I was completely fascinated by that refreshing way of looking at cinema and at women. And I think it has a timeless quality about it.

La tia Tula, by Miguel Picazo, illustrates very well with its realist approach provincial society in 60s Spain and it’s been a point of reference for Almodovar himself.

El extraño viaje, by Fernando Fernán Gomez, is one of my favorites. It is illustrative of the very Spanish tradition of esperpento. It’s fun. It’s crazy. It’s daring. It’s absurd. One can’t but wonder how it went through Franco’s censorship in 1964.

Te doy mis ojos, by Iciar Bollain, is another gem I think with two fantastic actors, Luis Tosar and Laia Marull. In a realistic and delicate way shows a dark side of Spain’s society.

Que Dios nos perdone / May God Save us is a film by Rodrigo Sorogoyen, from a younger generation. I think it is a terribly good film and representative of a maturity in Spanish cinema.

These are only a few of the many, many films I think could provide with a good introduction to Spanish cinema. This is perhaps just one of many ways to start.

“Me encanta cómo en España la gente es bastante paciente cuando estás aprendiendo la lengua”

Esta semana continuamos con la serie de entrevistas a personalidades del ámbito hispano-británico. Nuestro cuarto invitado, Xavier Bray, es un historiador del arte especializado en arte y escultura españolas. Es, además, el actual director de The Wallace Collection en Londres.

Previamente, Dr. Bray ostentó el título de comisario jefe de la Dulwich Picture Gallery y comisario adjunto de la colección de pinturas europeas de los siglos XVII y XVIII de la National Gallery de Londres. Además, ha sido comisario de diversas exposiciones tales como Lo sagrado hecho real: escultura y pintura españolas 1600 – 1700, Goya: retratos (2015) y, más recientemente, Ribera: arte de violencia (2018) .

Bray completó su tesis doctoral en 1999, titulada «Comisiones reales religiosas como propaganda política en la España de Carlos III«, en el Trinity College de Dublín.

– Durante los últimos cinco años, has trabajado como director de la Wallace Collection, ¿podrías resumir esta experiencia para nuestra audiencia?

La Wallace Collection es una colección increíble. Es uno de los mejores museos del mundo, con una impresionante diversidad de obras de arte, desde pintura y escultura hasta porcelana. Para mí, personalmente, ha sido una gran oportunidad el poder aprender sobre diferentes tipos de arte, sobre todo porque mi especialidad es solo la pintura barroca. He tenido un equipo de comisarios muy buenos, un equipo pequeño pero muy dinámico. Además, supongo que lo que estoy intentando hacer es convertir la Wallace Collection en un lugar que todo el mundo pueda disfrutar. Esa es nuestra misión más importante y nos estaba yendo bastante bien, hasta el inicio de la cuarentena.

– Eres un famoso especialista en arte de los siglos XVII y XVIII, por el cual es famosa la Wallace Collection. ¿Podríamos decir que estáis hechos el uno para el otro?

Es verdad que, cuando era estudiante, venía a analizar las colecciones de pintura, especialmente las de pintura española, francesa e italiana. Y entonces, por supuesto, realicé mi doctorado sobre Goya y la Wallace Collection es el lugar perfecto para estudiar pintores franceses del siglo XVIII. Te encuentras rodeado de Watteau, Boucher, Fragonard, Delacroix, Dolaroche y Meissonier. Es como volver al hogar que tan bien conocía. Es como si estuviéramos hechos el uno para el otro, pero a la vez, soy consciente de que quiero hacer más con otros tipos de arte e implicarme con diversas disciplinas, investigadores y técnicas. Pero, sí, por supuesto que ha sido una experiencia muy positiva trabajar en una colección tan rica y diversa.

¿Cómo se convirtió en especialista del Siglo de Oro español?

Mi padre trabajaba como periodista para el Wallace Street Journal en Madrid. Yo tenía alrededor de 14 años en ese momento. Desgraciadamente, yo me encontraba en un internado en Inglaterra mientras mis padres estaban pasándoselo genial en el Madrid de los 80, una gran década para España. Volví durante las vacaciones para pasar un tiempo en Madrid y El Prado fue el primer museo que descubrí. Allí encontré a Velázquez, Zurbarán, y después, al gran Goya. La verdad es que acercarme a la obra de éste, me ponía muy nervioso ya que le consideraba un artista complejo y difícil. Era muy variado, creando bellas pinturas de la vida de Madrid en sus cartones, pero a la vez tenía sus Pinturas Negras, que son el más perturbador testimonio de la humanidad fracasando.

– Habla un español excelente, ¿podría contarnos un poco más sobre cómo lo aprendió?

Aprendí español cuando tenía 16 o 17 años, en Inglaterra. Por suerte, mis padres estaban en Madrid y yo me esforzaba por practicarlo cuando estaba allí. Me encanta cómo en España la gente es bastante paciente cuando estás aprendiendo la lengua y no tienen problema en ayudarte. En España es realmente fácil sumergirse en la cultura, la tradición, las gentes, la propia lengua, la literatura, etc. También viví en Granada durante un año sabático. Simplemente el estar allí, vivir la vida y conocer a todo tipo de personas de diferentes círculos enriqueció realmente mi experiencia. El mejor consejo para estudiantes de lengua española es pasar en España el mayor tiempo posible.

– Usted dirigió el programa de conservación del Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao. ¿Cuáles son tus recuerdos de esa época ahora que estás en Londres?

Siempre he tenido especial afecto por Bilbao y este museo. Es un museo maravilloso de Bellas Artes. En aquellos días, trabajé para Miguel Zugaza. Allí trabajé mucho, gracias a él, pero también tuve la gran oportunidad de trabajar en un museo europeo y trabajar con una colección que incluyó a los grandes maestros además de una colección de pintura vasca del siglo XIX. Allí había un fuerte sentimiento de identidad nacional. Lo recuerdo con aprecio, me trae muy buenos recuerdos y siempre estoy pensando en formas de trabajar con el Museo de Bellas Artes de Bilbao.

– Usted tiene fama de apostar por la experimentación y de tomar riesgos en tu trabajo como comisario, ¿cómo puso este aspecto en práctica en la Wallace Collection?

Comisariar y organizar exhibiciones es algo que me apasiona. No me gusta repetir cosas y siempre intentaré impulsar las exposiciones y probar ideas nuevas, tratando de aportar nuevas perspectivas o artistas o períodos. Siempre trato de hacer más vital una exposición, aportando algo relevante en relación con aquello que esté ocurriendo en el presente. La exposición más reciente en la Wallace Collection, que en teoría sigue expuesta, es la primera muestra de obras de pintores indios encargada por oficiales de la East India Company, lo que supone un área de arte sin precedentes, nunca antes considerada.

– Nos acordamos especialmente de cómo rastreó la trayectoria de Goya desde sus principios en la corte de Carlos III en Madrid hasta sus años finales en Burdeos. ¿Cómo recuerda esta exposición?

Era una exposición de los retratos de Goya y no era tan obvio realizarla contando la historia de su vida a través de los retratos de gente que le habría conocido. Fue una de esas experiencias maravillosas. Reuniendo todos los amigos de Goya, así como reinas y políticos, pudimos reconstruir su vida de una manera muy diferente. No era sobre cómo Goya se veía a sí mismo, sino sobre las impresiones de personas que conoció y las conexiones que tuvo. Y, de repente, el resultado fue la capacidad de ver a Goya de una manera muy diferente. Y, para mí, y espero que para los visitantes también, fue una experiencia extraordinaria el entender los círculos en los que se movió y sus amistades; tienes la oportunidad de conocer a este hombre extraordinario y a su alma. Es raro poder hacer eso con un artista. Fue una experiencia muy satisfactoria y me hubiera gustado poder estar allí por la noche, para oír sus conversaciones. Fue una de esas exposiciones dinámicas, donde podrías esperar que los cuadros comenzaran a hablar.

La crisis del Covid-19 ha provocado el cierre de todos los museos. ¿Habéis lanzado algún programa en línea en la Wallace Collection para este periodo especial?

Por supuesto, como todo museo, queremos asegurarnos de no desaparecer. Estamos muy preocupados de que todo el mundo se esté centrando en muchas otras cosas, lo cual está bien, pero el mayor problema es cómo conseguir que un museo como la Wallace Collection siga siendo relevante hoy en día. Estamos lanzando una serie de temas digitales con los que la gente puede involucrarse en nuestra página web. Tengo la esperanza de, si acudir al lugar del trabajo es posible, volver a la galería y realizar una grabación en directo sobre la exhibición Indian Animals. Además, esperamos poder reabrir pronto y continuar con nuestro programa. Tenemos una exposición sobre Rubens dentro de poco que reúne dos de sus grandes paisajes por primera vez. Uno es Paisaje con arcoíris (de la Wallace Collection) que yo creo que se ha vuelto más emotivo que nunca en los últimos meses. El arcoíris se ha convertido un símbolo de esperanza en Reino Unido y del gran trabajo del NHS, así que espero que este cuadro tenga un fuerte impacto en nuestra sociedad como una imagen de supervivencia y creatividad. En realidad, este es un gran momento para la creatividad.

Traducción: Blanca Gomez Garcia

“I love that in Spain, people are quite patient when you are learning the language”

This week, we continue a series of interviews with personalities from the Spanish-British sphere. Our fourth guest, Xavier Bray, is an Art Historian specialising in Spanish art and sculpture. He is the current Director of the Wallace Collection in London.

Formerly, Dr Bray held the title of Chief Curator at the Dulwich Picture Gallery and Assistant Curator of 17th and 18th-century European paintings at the National Gallery, London. Furthermore, he has curated several exhibitions including The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Sculpture and Painting 1600-1700 (2009), Goya: The Portraits (2015) and, most recently, Ribera: Art of Violence (2018).

Dr Bray completed his PhD in 1999, (entitled, ‘Royal Religious Commissions as Political Propaganda in Spain under Charles III’) at Trinity College, Dublin.

– For the past five years, you have been the director of the Wallace Collection, could you summarise this experience for our audience?

The Wallace Collection is an unbelievable collection. It’s a world class museum, with such an incredible diversity of works of art, ranging from paintings and sculpture to porcelain. For me personally, it’s been a great opportunity to learn about the different arts, particularly as I am a specialist only in Baroque painting. I have a team of very good curators, it is a small team but very dynamic. And I suppose that what I am trying to do is to make the Wallace Collection a place for everyone to enjoy. That’s our most important mission and we were doing quite well, until the lockdown.

– You are a renowned specialist in 17th- and 18th-century art, for which the Wallace Collection is famous, could we say it is a perfect match?

It’s true that when I was a student I came to study the painting collections, particularly the Spanish, the French and the Italian. And then, of course, I did my PhD on Goya and the Wallace Collection is the perfect place to study the 18th-century French painters. You’re among the likes of Watteau, Boucher, Fragonard, Delacroix, Delaroche and Meissonier. It was like returning to a home that I knew well. It’s the perfect match, but at the same time, I am very aware of wanting to do more with the other arts and engage with different kinds of disciplines, scholars and techniques. But, yes of course it has been a very happy experience to work in such a rich and diverse collection.

– How did you become a specialist in Spanish Golden Age art?

My father was a journalist working for the Wall Street Journal in Madrid. I was about 15 at that time. Unfortunately, I was set to boarding school in England while my parents were having a great time in Madrid in the 1980s, a great decade for Spain. I came back for the holidays, to spend time in Madrid and the Prado was the first museum I discovered. There I found Velázquez, Zurbarán, and then, the great Goya, who I was actually very nervous of approaching, because I found him a very complicated and difficult artist. He was so mixed; simultaneously creating beautiful paintings of Madrid life in his cartoons and alongside the Black Paintings, which are the most disturbing testimonies of humanity going wrong.

– You speak Spanish excellently, could you tell me a bit more about it?

I learnt it when I was about 16 or 17 whilst in England. Luckily, my parents were in Madrid and I tried to practice it hard when I was there. I love that in Spain, people are quite patient when you are learning the language, and they help you out. It is very immersive in Spain, you can immerse in the tradition, with people, the language itself, the literature, etc. I also took a year off and I lived in Granada. It was just being there and living life and meeting all kinds of people from different circles that really enriched my experience. The best advice to students of the Spanish language is to spend as much time in Spain as possible.

– You lead the curatorial programme at the Museo de Bellas Artes in Bilbao. What are your memories of that time now that you are in London?

I have always been very fond of Bilbao and the museum there. It’s a great museum of Fine Arts. In those days, I worked with Miguel Zugaza. I learnt so much there, thanks to him, but I also had the great opportunity of working in a European museum, and to work with a collection which included old masters as well as a great collection of Basque paintings of the 19th-century. There was a strong national identity there. I remember it fondly, of good memories and I am always thinking of new ways to work with the museum of Fine Arts in Bilbao.

– You have a reputation for experimentation and risk-taking in curating, how did you put it into practice at the Wallace Collection?