Blog del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín

Torre Martello

Audiolibro de la semana | Audiobook of the Week: Los girasoles ciegos

Esta semana te traemos en forma de audiolibro uno de los libros más reconocidos en la literatura española reciente: Los girasoles ciegos de Alberto Méndez. Para descargar esta gran novela, solamente necesitas tu carnet de la biblioteca y hacer click aquí.

Esta semana te traemos en forma de audiolibro uno de los libros más reconocidos en la literatura española reciente: Los girasoles ciegos de Alberto Méndez. Para descargar esta gran novela, solamente necesitas tu carnet de la biblioteca y hacer click aquí.

Un capitán del ejército de Franco que, el mismo día de la victoria, renuncia a ganar la guerra; un niño poeta que huye asustado con su compañera niña embarazada y vive una historia vertiginosa de madurez y muerte en el breve plazo de unos meses; un preso en la cárcel de Porlier que se niega a vivir en la impostura para que el verdugo pueda ser calificado de verdugo; por último, un diácono rijoso que enmascara su lascivia tras el fascismo apostólico que reclama la sangre purificadora del vencido.

Son historias de los tiempos del silencio, cuando daba miedo que alguien supiera que sabías. Cuatro historias, sutilmente engarzadas entre sí, contadas desde el mismo lenguaje pero con los estilos propios de narradores distintos que van perfilando la verdadera protagonista de esta narración: la derrota. Premio Nacional de Literatura 2005, Premio de la Crítica 2005, Premio Setenil 2004.

This week we bring you the audiobook of one of the most remarkable novels of recent Spanish literature: Los girasoles ciegos by Alberto Méndez. If you want to download this great novel, you just need your library card and make click here.

A captain who is on Franco´s side renounces to win the war on the very same day of the victory; a young poet runs away with his pregnant young partner and lives a vertiginous story of maturity and death in a brief period of time; a prisoner of the Porlier jail refuses to live a lie in order the executioner can be called executioner; finally, a lecherous deacon hides his lust behind the apostolic fascism that claims for the purifier blood of the defeated.

These are stories about those times of silence when you were scared that someone knew that you knew. Four stories subtly connected, narrated with the same language but with the different styles used by the narrators that shape the real protagonist of the novel: defeat. National Award of Literature 2005, Critics Award 2005, Setenil Award 2004.

La biblioteca propone: Cine y literatura de terror / The library suggests: Horror film and literature

Ya pasaron los sustos de Halloween, pero antes de que llegue la Navidad, el mes de noviembre es ideal para acercarse al género de terror en el cine y en la literatura, un género que gana más adeptos cada día. Ese es precisamente nuestro tema destacado del mes.

Ya pasaron los sustos de Halloween, pero antes de que llegue la Navidad, el mes de noviembre es ideal para acercarse al género de terror en el cine y en la literatura, un género que gana más adeptos cada día. Ese es precisamente nuestro tema destacado del mes.

Considerado con frecuencia un género menor tanto en la literatura como en el cine, el género de terror, que también cuenta con obras maestras, nos ha hecho disfrutar a todos del placer del miedo. Acércate a nuestra biblioteca y descubre por qué.

For this month, the library suggests a selection of horror books and films. Horror genre is often considered a minor subject in literature and cinema. As we have just survived Halloween and once again we were scared to death, we would like to vindicate the quality of many of the books and movies specially created to be enjoyed while we are frightened.

In fact, and opposite to what happens in other sub-genres as Science Fiction or Fantastic Literarure, where we can find writers focussed on writing exclusively this kind of books, the horror genre has always attracted a wide variety of writers who have made punctual contributions to the genre, especially with short-stories.

Novedades en la biblioteca: noviembre 2012 / New to the library: November 2012

Las novedades de la biblioteca pueden ser consultadas en nuestro catálogo en línea, como es habitual.

Las novedades de la biblioteca pueden ser consultadas en nuestro catálogo en línea, como es habitual.

Para ello, seleccione ÚLTIMAS ADQUISICIONES y elija el período de tiempo que le interesa: ”el último mes” o “los últimos tres meses”.

Ésta es nuestra selección para los meses de noviembre de 2012.

The lastest additions to the library catalogue can be consulted on line as usual.

Click ÚLTIMAS ADQUISICIONES and choose the time period: “el último mes” or “los tres últimos

meses”.

This is our selection for November 2012.

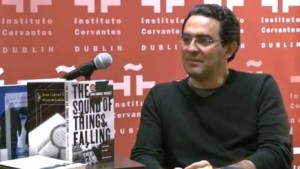

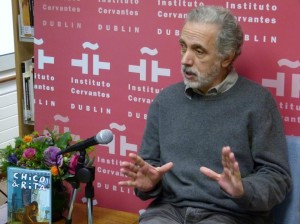

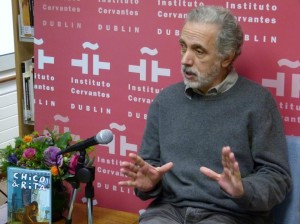

Entrevista con Juan Gabriel Vásquez

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: Escribe solo si sientes que no serás feliz de otra manera

Entrevista con Juan Gabriel Vásquez realizada el 14 de noviembre de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de la presentación de la traducción al inglés de su libro El ruido de las cosas al caer.

Juan Gabriel Vásquez (Bogotá, 1973) es autor de la colección de relatos Los amantes de Todos los Santos y de las novelas Los informantes e Historia secreta de Costaguana. También ha publicado una recopilación de ensayos literarios, El arte de la distorsión (que incluye el ensayo ganador del Premio Simón Bolívar en 2007), y una breve biografía de Joseph Conrad, El hombre de ninguna parte. Ha traducido obras de John Hersey, John Dos Passos, Victor Hugo y E. M. Forster, entre otros, y es columnista del periódico colombiano El Espectador. Sus libros se han publicado en catorce lenguas y una treintena de países. Su tercera novela, El ruido de las cosas al caer, ganó el Premio Alfaguara en 2011.

Sergio Angulo: —Juan Gabriel, El ruido de las cosas al caer es tu última novela ¿nos puedes contar algo sobre ella?

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —La novela trata sobre un profesor joven de derecho llamado Antonio Yammara que un día conoce a un personaje misterioso, un tipo llamado Ricardo Laverde, que evidentemente tiene algo que ocultar, que evidentemente no es quien dice ser. Y lo que comienza siendo una curiosidad frívola se convierte en algo más serio cuando asesinan a Ricardo Laverde a tiros en la calle, mediante un asesino a sueldo. El narrador del libro es alcanzado por una bala, un balazo directo que, evidentemente, cambia su vida, y se obsesiona con la idea de que averiguar quién era este tipo y por qué fue asesinado le permitirá obtener alguna verdad sobre lo que le ha pasado a él, sobre la manera en la que su vida ha cambiado. Así que se embarca en una investigación personal sobre la vida de un hombre muerto y sobre el pasado de Colombia, y eso lo devuelve a los años en los que el mercado de la droga comenzó en Colombia, a principios de los setenta.

Averiguamos que este hombre era piloto, y que no fue solo testigo, sino que también tomó parte en los primeros momentos del mercado de la droga. Y así, la novela se convierte en una especie de exploración de lo que ha significado para mi generación crecer al mismo tiempo que el mercado de la droga y, particularmente, lo que significó para nosotros sufrir los peores años de la violencia relacionada con la guerra de la droga de los ochenta, cuando Pablo Escobar, básicamente, declaró la guerra al gobierno colombiano. Eso es lo que he intentado explorar.

Sergio Angulo: —La historia no está basada en hechos reales, pero de alguna manera refleja la realidad de una era en Colombia.

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —Es un trabajo de la imaginación, y he intentado explorar cosas que realmente pasaron. Una de mis obsesiones, evidentemente, ha sido, no solamente en esta novela, sino en otras novelas también, cómo los hechos públicos moldean nuestras vidas privadas. Esta es una de las cosas que me interesan como novelista. Cómo esas cosas que pasaron en lo que llamamos «historia» o «política» penetran en nuestras vidas y afectan el modo en que nos comportamos como amigos o parejas, padres o hijos. Eso es lo que mi novela intenta hacer.

Una de las razones para escribir una novela es la reflexión sobre aquellos años, sobre aquel período de nuestras vidas. Teníamos mucha información pública, un montón de estadísticas, un montón de imágenes en los medios de comunicación. Podemos incluso encontrar el vídeo de un candidato a presidente de Colombia siendo asesinado. Pero en algún momento, me sentí angustiado ante la idea de que no había ningún lugar donde pudiéramos ir para averiguar sobre los efectos íntimos y privados que todo eso tuvo. Así que en cierto sentido, el novelista que quería ser es una especie de historiador de emociones. Intenta averiguar cuál es el lado moral y emocional de esos hechos que son públicos.

Sergio Angulo: —Estuviste viviendo en Francia durante un tiempo y, por lo que sé, ahora estás establecido en España, en Barcelona. ¿Ha tenido la distancia algún efecto en tu manera de ver Colombia?

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —Es muy difícil probar eso, pero siempre he dicho que si pude escribir sobre Colombia es porque dejé Colombia. Mi primer libro es un libro de historias sobre Bélgica y Francia, y la gente me preguntaba por qué no escribía sobre Colombia y la gente de allí. Y la razón, para ponerlo en pocas palabras, es que como sentía que no lo entendía, que no entendía realmente a mi país, no tenía derecho a escribir sobre él. Y creo que por la distancia, por el tiempo que pasé fuera, y porque había un océano entre mi país y yo, terminé dándome cuenta de que quizás el hecho de que no entendiera mi país era el mejor motivo para escribir sobre él, que podría usar la novela como una manera de comprender mejor la historia de mi país y cómo me ha modelado como individuo.

Sergio Angulo: —Barcelona es históricamente una ciudad donde muchos de los autores latinoamericanos más importantes han vivido. Y ahora que estamos celebrando el cincuenta aniversario del boom latinoamericano, ¿qué queda de ese boom literario?, ¿se está expandiendo todavía, o hay un punto de inflexión con las nuevas generaciones, ya que estáis llevando caminos distintos?

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —Siempre he considerado a los escritores del boom Latinoamericano como los fundadores de mi tradición. La tradición en la que yo intentaba escribir empezó con ellos. Antes que ellos, la novela latinoamericana había producido un par de trabajos aislados. Trabajos muy interesantes, pero aislados. No había una tradición de novelas latinoamericanas en las que basarse. Eso comenzó con ellos, con Vargas Llosa, García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes, Julio Cortázar. Ellos siguen estando muy presentes para mí, en el sentido de que todavía viven. Vargas Llosa y García Márquez todavía viven. Vargas Llosa todavía escribe. Pero al mismo tiempo son clásicos. Son clásicos en vida. Y para mí, como he dicho antes, compartir el mismo mundo con ellos es casi como si un escritor irlandés del siglo XXI pudiera coger el teléfono y llamar a James Joyce, porque estos tipos son los fundadores de mi tradición. Así que es una situación muy rara y muy rentable. No me siento en modo alguno amenazado por su presencia, como les pasa a otros escritores. Creo que hay un gran legado que ha abierto muchas puertas a los que hemos venido después de ellos.

Sergio Angulo: Viviendo en Europa. ¿Crees que nuestra percepción de Latinoamérica es adecuada desde aquí?

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —Siempre hay cierto grado de inexactitud, pero funciona en los dos sentidos. Los medios de comunicación tienen una habilidad extraordinaria para distorsionar la imagen de un país, a veces simplemente porque tienen recursos limitados, tiempo limitado… Pero una de las cosas buenas de las novelas es que, de algún modo, luchan contra el cliché, el estereotipo, de modo que los lectores podemos obtener una mejor comprensión de la complejidad de los Estados Unidos cuando leemos a Philip Roth. Quizás un lector irlandés, o británico, pueda comprender mejor la complejidad, las contradicciones de Colombia, leyendo una novela como esta.

Sergio Angulo: —Eres muy joven, pero ya estás en la cima de la montaña del mundo literario. ¿Qué vista tienes cuando miras hacia abajo?

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —Prefiero mirar hacia arriba, hacia el siguiente libro y ver lo difícil que será escribirlo. Porque creo que una de las cosas crueles de este negocio es que cada libro es más difícil que el anterior. En el sentido de que sabes más cosas, eres más consciente de los obstáculos, los problemas y las dificultades de escribir. Uno no quiere repetirse. Soy de esos escritores que quieren cambiar con cada libro. Uno se mete cada vez más en esa idea arrogante de que podrá escribir un libro como esos libros que le gustan, y por eso sigue escribiendo. Uno sabe que es imposible escribir un libro como esos que lo convirtieron en escritor, pero en el intento, quizás dé al lector un par de buenas páginas, y quizás eso sea suficiente.

Sergio Angulo: —Y para terminar ¿algún consejo para uno de esos jóvenes escritores que está a los pies de la colina, preparando su libro y su mochila para comenzar a subir la montaña?

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —Bueno, siempre doy el mismo consejo que es muy simple pero muy honesto y creo que muy útil: Escribe solo si sientes que es absolutamente necesario, si crees que no serás feliz de otra forma. La vida de un escritor es muy difícil. Tendrás que sacrificar amigos, a la familia. Y los reconocimientos no importan, o no existen, ni el dinero. Escribe solo si eres consciente de que tu único premio será la satisfacción de un trabajo bien hecho.

Enlaces Recomendados

- [Vídeo] Entrevista realizada a Juan Gabriel Vásquez en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín por Sergio Angulo.

- Juan Gabriel Vásquez en El Espectador.

- Juan Gabriel Vásquez en Alfaguara.

Interview with Juan Gabriel Vásquez

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: Write Only if You Think That you will Be Unhappy Otherwise

Interview with Juan Gabriel Vásquez on the 14th November 2012, at the Dámaso Alonso Library of the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin, in association with his participation in the launch of his lastest novel, The Sound of Things Falling.

Juan Gabriel Vásquez (Bogotá, 1973) is the author of a collection of stories, Los amantes de Todos los Santos, and the novels Los informantes (The Informers, Riverhead Books, 2009) and Historia secreta de Costaguana (The Secret History of Costaguana, Riverhead Books, 2011). He has also published a collection of literary essays, El arte de la distorsión (which include an essay that won the Simón Bolívar Award in 2007), and a brief biography of Joseph Conrad, El hombre de ninguna parte. He has translated works by John Hersey, John Dos Passos, Victor Hugo and E. M. Forster, amongst others, and is a columnist for the Colombian newspaper El Espectador. His books have been published in fourteen languages and thirty countries. His third novel, El ruido de las cosas al caer, (The Sound of Things Falling, Bloomsbury, 2012) won the Alfaguara Award in 2011.

Sergio Angulo: —Juan Gabriel, The Sound of Things Falling is your latest novel, tell us about it.

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —The novel is the story of this young law professor called Antonio Yammara, who one day meets this mysterious character, a guy called Ricardo Laverde, who evidently has something to hide and is not who he says he is. What begins as this frivolous curiosity, turns into something more serious when this Ricardo Laverde gets killed by a sniper in the street, by a hit-man. The narrator gets hit by a bullet, a straight shot that obviously changes his life. He becomes obsessed with finding out who this guy really was and why he was killed, in order to reach some conclusions about what has happened to him and why his life has changed. So he embarks on this personal investigation, a personal enquiry into the life of a dead man and his past of Colombia. This sends him back to the years in which the drug trade effectively began in Colombia, the early seventies.

We learn that this guy was a pilot and he was not only a witness, but also a participant in the first phase of the drug trade. The novel becomes a sort of exploration of what it means to my generation to grow up surrounded by the drug trade, and particularly, what it means for us to have suffered through the worst years of drug-related violence – of the drug wars in the eighties, when Pablo Escobar basically declared war against the Colombian Government. This is what I have tried to explore.

Sergio Angulo: —The story is not a real case, but it somehow, portrays the reality of this era in Colombia.

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —It’s a work of fiction, but I tried to explore things that really happened. One of my obsessions has been, not only in this novel, but in my other novels too, how public events shape our private lives. This is one of the things that interests me as a novelist – how things that happened in what we call “history” or “politics” penetrate our lives and affect the way we behave as friends, or as couples, or as parents and children.

One of the reasons behind the writing of this novel was to realise that, in those years, during that period of violence, we had a lot of public information, we had a lot of statistics, a lot of images in the media, (we can even find the video of a presidential candidate in Colombia getting killed) but, at some point, I became anxious at the idea that there wasn’t a place we could go to find out about the effects all of this had had on private or personal lives. In a way, the novelist I wanted to be, is a sort of historian of emotions. I tried to explore the emotional and moral side of those very public events.

Sergio Angulo: —You were living in France for a while and, as far as I know, you are now based in Spain, in Barcelona. Has this distance had any effect on the way you see Colombia now?

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —It’s very difficult to prove, but I’ve always said that, the only reason I´m able to write about Colombia, is because I have left. My first book was a book of stories about Belgium and France, and people used to ask me, “Why don’t you write about Colombia?” And the reason, to sum it up in a nutshell, is that I felt that, since I didn’t really understand my country, I wasn’t allowed to write about it. But because of the distance, because of the time I spent abroad, and because there was an ocean between my country and me, I ended up realising that, perhaps the fact that I didn’t understand my country was the best reason to write about it. I could use novels as a way of understanding the history of my country and how that has shaped me as an individual.

Sergio Angulo: — Historically, Barcelona is a place where many of the most important Latin American authors have lived. Now we are celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Latin American literary boom. Is this literary boom still happening, or has there been a turning point with new generations taking different paths?

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —I always considered the writers of the Latin American boom as the real founders of my tradition. The tradition in which I tried to write began with them. Before them, the Latin American novel had maybe produced a couple of isolated things, very interesting things, but isolated. There wasn’t a tradition of Latin American novels to speak of. It all began with Vargas Llosa, García Márquez, Carlos Fuentes and Julio Cortázar. So, in a way, they’re quite present for me, in the sense that they are all still living. Vargas Llosa and García Márquez are still living. Vargas Llosa is still writing. But, at the same time, they are classics. They are living classics, and for me, having them sharing the same world, is almost as if a 21st Century Irish writer could pick up the phone and call James Joyce. It’s a very strange situation, and a very profitable one. I don’t feel in any way threatened by their presence, as many writers do. I feel there is a very big legacy that has opened doors for the people who have come after them.

Sergio Angulo: —Living in Europe, is our perception of Latin America accurate?

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —There is always a certain degree of inacuracy. But it works both ways. The media have an extraordinary ability to distort the image of a country, sometimes through no fault of their own, because time in the media is limited, resources in the media are limited… But one of the nice things that novels do is, in a way, fight against cliché, against stereotypes, so perhaps we, as readers, get a much better understanding about the complexity of the United States, when we read Philip Roth. Maybe an Irish reader, or a British reader, will get a better understanding about Colombia and the complexity of life there, the contradictions, the unpredictability of life in Colombia, when they read a novel such as this one. In any case, that’s what I would like to see happening.

Sergio Angulo: —You are very young, but you are already at the peak of the literary world. How is the view when looking down?

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —In reality, I’m looking towards the next book, and wondering how difficult it will be to write it, because one of the cruel things of this trade is that every book is more difficult than the last one, in the sense that you know more things, you’re more conscious of the pitfalls and the problems, and the difficulties of writing. You don’t want to repeat yourself. I’m one of those writers who wants to change with every book. You always get deeper and deeper into this arrogant mindset that you can write a book like the books you love. And I think that’s what you constantly strive to do. You never get to do it, of course, because it’s impossible to write a book like those books that made me want to become a writer. But I think in the attempt to accomplish this, you might give the reader a couple of nice pages, and that’s probably enough.

Sergio Angulo: —Finally, any advice for a young writer who is at the bottom of the hill, getting his book and his backpack ready to start climbing the mountain?

Juan Gabriel Vásquez: —Well, I always give the same piece of advice, which is very simple but very honest, and I think it’s very useful, – Write only if you feel it’s absolutely necessary. The writing life is a very difficult life to live. You have to sacrifice friends, you have to sacrifice time with your family, so write only if you think that you will be unhappy if you don’t do it. Forget about the money, the reviews… they don’t matter. Write only if you know that your only reward will be the satisfaction of a job well done.

Recommended links

- [Video] Interview with Juan Gabriel Vásquez at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin by Sergio Angulo.

- Juan Gabriel Vásquez in El Espectador.

- Juan Gabriel Vásquez in Alfaguara.

Presentación de libro: “El ruido de las cosas al caer” de Juan Gabriel Vásquez | Book launch: “The sound of things falling” by Juan Gabriel Vásquez

Hoy a partir de las 19:00 horas podrás disfrutar de la presentación de la traducción al inglés del último libro del autor colombiano Juan Gabriel Vásquez. El acto tendrá lugar en el Café Literario.

Hoy a partir de las 19:00 horas podrás disfrutar de la presentación de la traducción al inglés del último libro del autor colombiano Juan Gabriel Vásquez. El acto tendrá lugar en el Café Literario.

Se le considera uno de los mejores novelistas de su generación, y El ruido de las cosas al caer, que aborda el devenir de Colombia durante la época de Pablo Escobar, es hasta la fecha su mejor novela.

Tan pronto conoce a Ricardo Laverde, el joven Antonio Yammara comprende que en el pasado de su nuevo amigo hay un secreto, o quizá varios. Su atracción por la misteriosa vida de Laverde, nacida al hilo de sus encuentros en un billar, se transforma en verdadera obsesión el día en que éste es asesinado.

Convencido de que resolver el enigma de Laverde le señalará un camino en su encrucijada vital, Yammara emprende una investigación que se remonta a los primeros años setenta, cuando una generación de jóvenes idealistas fue testigo del nacimiento de un negocio que acabaría por llevar a Colombia —y al mundo— al borde del abismo.

Juan Gabriel Vásquez (Rosario, Colombia, 1973) estudió derecho en su ciudad natal y más tarde se doctoró en Literatura Latinoamericana en La Sorbona. Actualmente reside en Barcelona. Es autor de tres novelas “oficiales” —Los informantes, Historia secreta de Costaguana y El ruido de las cosas al caer—, aunque escribió otras cuando tenía 23 y 25 años de edad, que él prefiere eliminar. Sus novelas han sido traducidas en Inglaterra, Francia, Holanda, Italia y Polonia.

We are delighted to invite you to the book launch of the translation into English of the last novel written by Colombian writer Juan Gabriel Vásquez. The event will take place today at 7pm at Café Literario.

Juan Gabriel Vasquez is one of the leading novelists of his generation, and The Sound of Things Falling that tackles what became of Colombia in the time of Pablo Escobar is his best book to date.

No sooner does he get to know Ricardo Laverde than young Antonio Yammara realises that his new friend has a secret, or rather several secrets. Antonio’s fascination with the life of Laverde begins by casual acquaintance in a billiard hall and grows until the day Ricardo is murdered.

More out of love with life than ever, he starts asking questions until the questions become an obsession that leads him to Laverde’s daughter. His troubled investigation leads all the way back to the early 1960s, marijuana smuggling and a time before the cocaine trade trapped a whole generation of Colombians in a living nightmare of fear and random death.

Juan Gabriel Vásquez (Rosario, Colombia, 1973) studied law in his hometown and obtained a phd in Latin American Literature in the Sorbone University. At present he lives in Barcelona. He has published three “official” novels – The informers, The secret history of Costaguana and The Sound of Things Falling— however he wrote others at the age of 23 and 25 which he prefers to omit. His works have been translated in England, France, Netherlands, Italy and Poland.

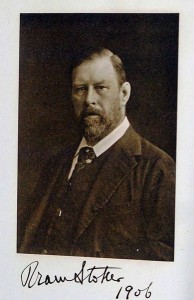

¡Felicidades Bram Stoker! / Happy birthday Bram Stoker!

Hoy se cumplen 165 años del nacimiento del escritor irlandés Bram Stoker, este año se cumple también el centenario de su fallecimiento, en abril de 1912. Con este motivo, la ciudad de Dublín, ciudad siempre literaria, se ve colmada de actividades en honor del autor de Drácula. Y claro está, en el Instituto Cervantes no podíamos ser menos. Por ello, el día 28 de noviembre celebramos un homenaje al escritor dublinés que contará con la presencia de Luis Alberto de Cuenca y Alicia Mariño. La charla será moderada por el Dr. Jarlath Killen, profesor de Literatura Victoriana del Trinity College Dublin.

Hoy se cumplen 165 años del nacimiento del escritor irlandés Bram Stoker, este año se cumple también el centenario de su fallecimiento, en abril de 1912. Con este motivo, la ciudad de Dublín, ciudad siempre literaria, se ve colmada de actividades en honor del autor de Drácula. Y claro está, en el Instituto Cervantes no podíamos ser menos. Por ello, el día 28 de noviembre celebramos un homenaje al escritor dublinés que contará con la presencia de Luis Alberto de Cuenca y Alicia Mariño. La charla será moderada por el Dr. Jarlath Killen, profesor de Literatura Victoriana del Trinity College Dublin.

Luis Alberto de Cuenca (Madrid, 1950) escribe lo que él denomina poesía transculturalista en la cual lo trascendente se codea con lo cotidiano y la cultura popular se mezcla con la literaria. Fue director de la Biblioteca Nacional y Secretario de Cultura del gobierno español.

Alicia Mariño es licenciada en Derecho y en Filología Francesa. Ha trabajado sobre el género fantástico en distintos autores y últimamente ha orientado su labor hacia la literatura comparada, estudiando la génesis y evolución de ciertas leyendas europeas.

Instituto Cervantes Dublin is pleased to invite Luis Alberto de Cuenta and Alicia Mariño, who will pay tribute to the Dubliner writer Bram Stoker. The talk will be chaired by Dr. Jarlath Killen, Lecturer in Victorian Literature at Trinity College Dublin.

This year we are conmmemorating the 100th anniversary of Bram Stoker´s death (1847-1912). Therefore, we would like to bring the figure of this Irish mathematician and novel and short story writer closer to you. Although his work was very prolific, he has been idolized and remembered by the creation of one of the most influential horror stories in history: Dracula.

Luis Alberto de Cuenca (Madrid, 1950), one of Spain’s most famous living poets, writes what he calls ‘transculturalist’ poetry in which the transcendental rubs shoulders with the everyday, and literary and popular cultures intermingle. He uses both free verse and traditional metres and his verse is famous for its ironic elegance and its scepticism.

Alicia Mariño has a degree in Law and in French Philology. She has worked on the fantasy genre and recently she has focused on comparative literature, studying the origin and evolution of some European legends.

El presidente Michael D. Higgins en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín / President Michael D. Higgins in the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin

El presidente de Irlanda, Michael D. Higgins, inauguró oficialmente la primera edición del Festival ISLA de Literatura el pasado 2 de noviembre en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín. y con ello contribuyó de manera decisiva a su éxito. El festival, por el que pasaron a lo largo del fin de semana cerca de mil asistentes, reunió a escritores de Argentina, Chile, Cuba, México, Irlanda y España en torno a una serie de lecturas, mesas redondas y proyecciones cinematográficas.

El presidente habló ante una sala abarrotada con cerca de 200 personas y les dio la bienvenida en español, irlandés, e inglés. Después de saludar a los asistentes, centró su alocución en los recuerdos de su reciente viaje diplomático por América Latina.

«He regresado recientemente de mi visita a Chile, Brasil y Argentina, una parte del mundo que tiene un lugar especial en mi corazón», dijo Higgins. «Durante este viaje, me llamó la atención una vez más la profundidad del compromiso con la cultura y la literatura irlandesa que existe en América Latina y cómo nuestras dos tradiciones se han influido y enriquecido mutuamente».

Higgins habló después sobre el papel que la escritora Kate O’Brien ha jugado en la literatura irlandesa y española, y la intensa conexión de la autora con España.

El amor del presidente por la poesía también se hizo evidente cuando aplaudió el énfasis que el Festival ISLA de Literatura hizo sobre este género en su programa. «Estoy impresionado por la profundidad y la fuerza de la poesía en este programa. Seamus Heaney, en su magnífica colección de ensayos «The Redress of Poetry», habla de cómo la poesía equilibra «la balanza de la realidad hacia un cierto equilibrio trascendente». El festival ISLA, con sus fuertes elementos interculturales, y los muchos poetas representados en él, como Maighread Medbh y Lorna Shaughnessy, parece tener esa inventiva deliciosa de la que Heaney habla en su obra».

El presidente finalizó leyendo el poema de Oliver St. John Gogarty «An Long» primero en lengua irlandesa y después en inglés.

Información basada en la nota de prensa de Megan Specia y Sergio Angulo.

Michael D. Higgins launched the first Irish, Spanish, and Latin America (ISLA) Literary Festival on the evening of November 2 in the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin. The festival, which brought together writers from Argentina, Chile, Cuba, Mexico, Ireland and Spain, was held over the weekend and featured a series of readings and round table discussions.

The President spoke to a crowd of approximately 200 participants and welcomed them in Spanish, Irish, and English. After greeting the crowd, he spoke to those gathered about a recent diplomatic trip to Latin America.

“I have recently returned from visiting Chile, Brazil, and Argentina, a part of the world which has a cherished place in my heart,” said Higgins. “During these visits, I was struck again by the depth of the engagement with Irish culture and writing that exists in Latin America and how our two traditions have influenced and enriched each other.”

Higgins went on to speak about the role than writer Kate O´Brien has played in Irish and Spanish literature, and the intense connection of the author to Spain.

The President´s love of poetry was also evident when he applauded ISLA´s emphasis on the genre. Said Higgins, “[I am] impressed by the depth and strength of poetic representation in the programme. Seamus Heaney, in his great collection on ´The Redress of Poetry´, speaks of how poetry balances ´the scales of reality towards some transcendent equilibrium´. The ISLA festival, with its strong intercultural elements, and the many poets represented like Maighread Medbh and Lorna Shaughnessy … would seem to have that self-delighting inventiveness of which Heaney speaks.”

He closed by reading Oliver St. John Gogarty´s poem “An Long” (The Ship) first in the Irish language and then in English.

Megan Specia & Sergio Angulo

Recital Literario | Literary Reading: “Poesía, por Diego Valverde Villena” (“Poetry, by Diego Valverde Villena”)

El Instituto Cervantes de Dublín y la National University of Ireland Maynooth tienen el placer de ofrecer al público irlandés este recorrido por la obra y la trayectoria del poeta hispano-peruano Diego Valverde, que realizará una lectura comentada de algunos de sus poemas y dialogará con la profesora del departamento de español, Catherine O’Leary, sobre sus influencias y carrera literaria.

El Instituto Cervantes de Dublín y la National University of Ireland Maynooth tienen el placer de ofrecer al público irlandés este recorrido por la obra y la trayectoria del poeta hispano-peruano Diego Valverde, que realizará una lectura comentada de algunos de sus poemas y dialogará con la profesora del departamento de español, Catherine O’Leary, sobre sus influencias y carrera literaria.

Diego Valverde Villena nació en San Isidro, Lima, Perú en 1967. Es poeta de nacionalidad peruana y española. Su vida siempre ha estado unida a la literatura. Entre 2002 y 2004 trabajó en la Secretaría de Estado de Cultura de España. Ha llevado a cabo estudios de especialización en lengua y literatura en las universidades de Salamanca, Edimburgo, Dublín y Wroclaw. Diego Valverde tiene una prolífica carrera como traductor de obras literarias desde el alemán, francés, inglés, italiano y portugués al castellano.

Instituto Cervantes Dublin and NUI Maynooth are delighted to present Spanish-Peruvian author Diego Valverde Villena, who will perform a commented reading of some of his poems and will discuss about his work, literary career and influcences with Ms Catherine O’Leary, lecturer of the Spanish Department.

Diego Valverde Villena, born on April 6, 1967, is a Spanish poet of Peruvian origin and Bolivian roots. In 1971, when he was four, his family left Peru for Spain. he also attended courses on language and literature in the University of Salamanca (Scandinavian languages), University of Edinburgh (Modernism), University College Dublin (Irish literature and culture) and the University of Wroclaw (Polish language and literature). From 2002 to 2004 he worked in the staff of the Secretary of State for Culture in Spain.

Entrevista con Javier Mariscal

Javier Mariscal: “El cerebro no es nada frío, es completamente sentimental”

Entrevista con Javier Mariscal realizada el 4 de noviembre de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en la mesa redonda “Palabras e imágenes: cine y literatura” junto a Mark O’Halloran y David Trueba dentro del Festival Isla de Literatura 2012.

Javier Mariscal (Valencia, 1950) es ante todo un creador de imágenes que desarrolla su trabajo en todo tipo de soportes y disciplinas. Junto con el equipo del Estudio Mariscal, que fundó en 1989, ha realizado numerosos proyectos internacionales (H&M, America’s Cup, Camper, etc.), además de la exposición sobre su trabajo Mariscal Drawing Life en el Design Museum de Londres y dos publicaciones monográficas: Mariscal Drawing Life y Sketches. En 2010, dirigió junto a Fernando Trueba, Chico y Rita y publicó el cómic Chico & Rita. En 2011 publicó también el libro ilustrado Los Garriris. Chico & Rita fue traducido al inglés en 2011.

Vanesa Zafra: —Javier, me interesa mucho el proceso creativo de los diseñadores ilustradores. ¿Cómo es el tuyo?, ¿por dónde empiezas?

Javier Mariscal: —En todos los procesos de diseño, lo primero es entender muy bien el problema que tienes que resolver. De alguna manera, yo entiendo mi estudio como una tienda que abrimos por la mañana y llega gente diciendo «tengo un problema de comunicación». Por ejemplo: «quiero hacer un disco donde salga Pedrito Hernández, que es un cantante rumbero cubano que vive en Nueva York. Le gusta mucho toda la música de Camarón de la Isla…» Bueno, pues a partir de toda la información que vas recibiendo, te planteas cómo ordenarla. Si estamos hablando de un muchacho que es cubano, que canta rumba y canciones de Camarón de la Isla, eso, de entrada, tiene ya un color.

Luego estan los límites. En este caso, no puedes decir «mira, te voy a hacer un disco así de grande». Porque entonces, en las librerías y en las tiendas, ¿dónde lo van a poner? Hay unos formatos establecidos. No te puedes inventar nada. El disco será redondo. Tienes también limitaciones de imprenta y de presupuesto. Quizas no puedas hacer un desplegable porque vale mucho dinero.

¿Cuáles son las herramientas? Tipografía, color, ilustración, fotografía… Y a partir de ahí, lo que haces, como digo, es ordenar esta información y ponerla de una manera que produzca una visión rápida y, sí puede ser, que toque el corazón. Porque, ¿por dónde nos comunicamos? Nos comunicamos por los sentimientos. El cerebro no es nada frío, es completamente sentimental.

Vanesa Zafra: —¿Es esa la filosofía de tu estudio? ¿La emoción, el humor, la diversión? ¿Cómo se estructura eso dentro de un equipo de mucha gente?

Javier Mariscal: —Pues no tengo ni idea. Son questiones que yo no me pregunto. Eso es algo más bien a posteriori, que es una palabra muy rara. No lo sé. Es una manera de plantear las cosas. Yo toda mi vida, desde que soy pequeño, cojo una piedra y digo “mira un avión”. Y entonces mis hijos, o todo el mundo dicen: “ah sí mira”. “Cuidado cuidado”. “Pues mira yo aquí tengo otro”. “¡Que van a chocar!” Y es una manera de entenderse y de comunicarse bestial que aprendemos de muy pequeños. Yo he visto a niños ingleses y catalanes jugar y no hablaban ningún idioma, pero se entendían en seguida. Con “shun chin chin pan chu pan chi pa cha”. Es el primer lenguaje realmente potente que aprendemos de pequeños. Pero hay mucha gente que al cumplir 12 o 15 años lo corta: “No no no. Esto ya no es un avión, esto es una piedra. Fuera”.

Yo, como diseñador, y yo creo que la gran mayoría de diseñadores, nunca he dejado de trabajar con ese sistema de pensamiento que es jugar. Ahí es donde de repente puedes pensar que hay cierto humor. Bueno, es jugar y jugar. Ahora empiezan a no insultarme, pero durante mucho tiempo me han insultado mucho. Por jugar.

Vanesa Zafra: —Todos nacemos creativos y vamos perdiendo esa cualidad cuando vamos aprendiendo cosas para ser adultos. ¿Se puede invertir el proceso?

Javier Mariscal: —Ser creativo es como respirar. Todo el mundo es creativo y desde que nacemos somos creativos. Es algo que tenemos porque si no te mueres. Se ve en seguida. Tú coges unos zapatos como estos que tienen tantos cordones y eres muy creativa y te haces un sistema para sacártelos y ponértelos de la manera más fácil. Y ahí está la creatividad. No sé porque se dice eso de “vosotros los creativos”. Y bueno ¿usted qué es? ¿Usted se piensa que no es creativo?.

Vanesa Zafra: —¿Escuchas música cuando trabajas?

Javier Mariscal: —Hay veces que no, hay veces que sí. Ha habido temporadas que era como un vicio. Era imposible trabajar sin música.

Vanesa Zafra: —Recomiéndame un disco.

Javier Mariscal: —Yo te recomendaría “Lágrimas negras”, uno de los mejores discos que se han podido producir en los últimos veinte siglos. Porque en la época de los romanos habia discos muy buenos, lo que pasa es que se han perdido.

Vanesa Zafra: —Algo que te haya sorprendido, algo creativo, un trabajo o una tendencia, quizas una película reciente.

Javier Mariscal: —Una película… Up, por ejemplo, maravillosa. Sobre todo el primer trozo. Pero claro, es evidente. Todo el mundo que la ha visto te dice “oye qué bonito y que fino es como empieza “Up”. Yo qué sé. Hace poco vi un corto, una cosita que hizo un amigo mío, que se llama Miguel Gallardo. Maravilloso. Hay miles y miles de cosas. Gracias a Dios, continuamente estas viendo trabajos, cosas de otra gente, que están muy bien. Que te quedas fascinado. Y es lo que necesitas para alimentarte Si no ¿de qué te alimentas?

Vanesa Zafra: —Y con Internet ahora, que puedes estar mirándolo todos los días…

Javier Mariscal: —Bueno, yo no pierdo tanto tiempo con Internet mirando todos los días ¿sabes? Me aburre cantidad.

Vanesa Zafra: —¿Y las redes sociales?

Javier Mariscal: —En las redes sociales he estado una temporada, de repente. Pero ahora no sé porqué ya llevo tiempo que no. No estoy en el Facebook. Y mira que yo era de publicar un dibujo cada día.

Vanesa Zafra: —Sí pero, ser esclavo de eso…

Javier Mariscal: —¿Esclavo? No, no, uno no es esclavo. Se hace por gusto, o no se hace.

Enlaces Recomendados

- [Vídeo] Entrevista realizada a Javier Mariscal en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín por Vanesa Zafra.

Entrevista con Fernando Trueba

Entrevista con Fernando Trueba realizada el 4 de noviembre de 2012 en la Biblioteca Dámaso Alonso del Instituto Cervantes de Dublín con motivo de su participación en la mesa redonda “Palabras e imágenes: cine y literatura” junto a Mark O’Halloran y Javier Mariscal dentro del Festival Isla de Literatura 2012.

Fernando Trueba (Madrid, España, 1955) es guionista, editor y director de cine. Entre 1974 y 1979 trabajó como crítico de cine para El País y en 1980 fundó la revista mensual de cine Casablanca, la cual dirigió y editó durante los primeros dos años. En 1992, su película Belle Époque, obtuvo 9 premios Goya y, en 1993, obtuvo el Oscar a la mejor película de habla no inglesa. En 1997 publica su libro Diccionario del cine y es editor del Diccionario del Jazz Latino (1998). En 2010 dirigió, junto al diseñador Javier Mariscal, la película de animación Chico y Rita, que recibió el Goya a la mejor película de animación y que fue seleccionada para el Oscar como Mejor Película de animación. Su última pelicula estrenada hasta el momento es El artista y la modelo (2012).

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Fernando, tengo grabado en la memoria el momento en que recibiste el Óscar por la película “Belle Époque”. Dijiste que no creías en Dios pero sí en Billy Wilder. ¿Todavía mantienes esa fe?

Fernando Trueba: —¿En Billy Wilder? ¿cómo no? ¿Por qué razón la iba a perder? Hay muchos directores a los que yo admiro y de los que intento aprender, y él es uno de ellos. Para mí han sido importantísimos en mi formación y en mi vida directores como Renoir, Truffaut, Bresson, Lubitsch, Preston Sturges y otros directores. Pero Billy Wilder forma parte de ese grupo de los que me han hecho a mí, para bien o para mal.

Yo siempre he pensado que Billy Wilder es el mejor guionista que ha existido nunca. Igual que pienso que es una tontería afirmar que alguien es el mejor director, porque un día puedes pensar que el Renoir, otro día que es Lubitch, otro que es John Ford y todos los días tienes razón. Ahora bien: yo desafío a cualquier persona a que me demuestre con los hechos que hay un guionista mejor que Billy Wilder. Que traiga los guiones, con los diálogos, cómo están escritos, construidos, y yo estoy dispuesto a tomarme el tiempo que sea, a analizarlo y discutirlo, porque estoy seguro de que no existe ese guionista por encima de Billy Wilder. Nunca existió.

Más que fe es una convicción. La fe es creer en algo sin verlo. Yo creo después de ver y leer, de sentir esa especie de revelación que uno siente cuando ve las obras maestras de Billy Wilder. Las sigues viendo y van pasando los años y las vuelves a ver. Te las sabes de memoria y piensas que ya no te va a pasar nada volviendo a ver Sunset Boulevard o El Apartamento o Double Indemnity o Some Like It Hot. Pero te vuelve a pasar. Vuelves a sentir esa admiración infinita ante la obra buena bien hecha, inteligente.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —¿Cómo se llega a un proyecto cinematográfico como el de Chico y Rita, en el que logras implicar a Bebo Valdés y a Mariscal?

Fernando Trueba: —Se llega por amistad. La amistad es uno de los móviles más grandes en mi vida, que está en el origen de muchas cosas que he hecho. En este caso, ha sido mi amistad con Mariscal. Todo empezó con Calle 54. Él me hizo el arte y todas esas cosas. Luego yo empecé a hacer discos y siempre le he pedido a él que me hiciera los diseños. Porque adoro lo que hace y porque nos entendemos muy bien. Me río mucho con él también.

Un día él me comenta «Yo me moriré sin haber hecho una cosa que me hubiera encantado: hacer una película de animación larga». Y le digo «seguro que habrás tenido mil propuestas ¿no? ¿Por qué no lo has hecho?» Y dice «ya, pero es que una película no son horas, son meses, años dibujando con tu manita y doblado encima de una mesa, y siempre que me lo han ofrecido era para una historia que no me gustaba. Yo no me voy a dejar la vida, los ojos y los brazos en dibujar una historia que no me gusta».

Claro, para mí la animación es un mundo totalmente ajeno, que nunca me había planteado. Entonces me dijo «por ejemplo, tú no te tomas en serio la animación y esas cosas. Tú nunca dedicarías el tiempo necesario para escribir un guión de una película de animación». Me pilló por sorpresa. Total, que con estas conversaciones empezó el proyecto. Un día, estando en su estudio, vi unos dibujos de él de la Habana vieja. Me entró una especie de ataque entusiasmo al verlos: «¡qué bonito! ¡Esto es lo que hay qué hacer! ¡Esta es la película que hay qué hacer! Una película en la Habana tuya, en la Habana Mariscal. ¡Eso sería prescioso!» Y así empezó. Y el me dijo: «Sí, pero tiene que tener música». «Hombre, si es una historia en la Habana y con cubanos, será dificil que no tenga música». «Sí, pero con mucha música», insistió. Entonces le dije, «porqué no hacemos una historia de músicos». «eso, un saxofonista y una cantante que se enamoran». Yo le dije que esa era la peor película de Scorcese, New York New York, odio esa película «Por qué no un pianista y asi, cada vez que toque el piano, metemos a Bebo Valdés». Así sale una película, poco a poco, como todo en la vida, a partir de una frase, de una imagen, de una conversación. Luego hay que ponerse a escribir y a dibujar durante años.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —El recorrido fue largo.

Fernando Trueba: —Sí, primero se hace el guión y se hacen muchas versiones. Luego, para convencer a la gente para que creyera en el proyecto y levantar el dinero que se necesita para hacer algo tan caro, había que mostrar el estilo que iba a tener la película. Entonces Xavi se puso a dibujar personajes, fondos, incluso produjimos unos planos de la película como muestra. Nos llevó varios años encontrar el dinero y gente para coproducir. Una vez que lo encuentras, habia que empezar los storyboards, los personajes y cientos de animadores dibujando durante dos años. En realidad, el proceso ocupó siete años. Lo que ocurre es que yo, entretanto, escribí el guión de otra película, produje otras películas, rodé en Chile El baile de la victoria. Si no, me hubiera muerto. Sobre todo porque hay partes de la película en las que yo ya no podía hacer nada más que esperar: ya había grabado el sonido, la música, diseñado el movimiento de la cámara. Solo tenía que esperar a que me llegaran los dibujos y comprobar que todo estaba bien.

Es muy raro lo de la animación. Para mí fue enfrentarme a un mundo totalmente nuevo y diferente. Debo decir que disfruté como como un niño. Salvo las esperas y lo largo que es y la paciencia que hay que tener. Cada vez que me llegaba un dibujo de Xavi, cada vez me llegaba un plano, era una alegría, era un subidón tremendo. De hecho estamos pensando en dos proyectos más. Chico y Rita nos ha abierto muchas puertas. Tenemos coproductores interesados en varios países en lo próximo que hagamos. Hay una historia muy de Xavi, basada en los personajes de los Garriris, de los primeros cómics de él, en cuyo guión está trabajando con un guionista. Y por mi parte, yo estoy escribiendo otra. Queremos hacerlas juntos. Pero una es un proyecto más de Xavi, más de su mundo y de sus cosas, y el otro es más un proyecto de una historia que yo quiero contar.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Los grandes aficionados al jazz siempre tienen una historia de amor con esta música. ¿Cuál es la tuya?

Fernando Trueba: —Yo he pasado por muchas épocas, porque descubrí el jazz siendo un adolescente a través de mi hermano mayor. Y me enganchó mucho. Me acuerdo en aquella primera época, de los 14, 15, 17 años, que me gustaba mucho Keith Jarret, Dei Brubek, McCoy Tyner. Luego hay una epoca en mi vida en la que me alejé del jazz, en la universidad.

Era la época del free jazz, que era demasiado free para mí. Me reventaba la cabeza. Era una especie de música para músicos, demasiado experimental. Hay un momento siempre, en todas las artes, cuando se han agotado todos los ismos, en que se entra en una especie de delirium tremens: «vamos a escribir sin comas», «ya no vamos a pintar, colocamos 27 teléfonos en el suelo y lo llamamos instalación»… En ese momento, yo me separo. El arte, en el momento en que se corta la comunicación, deja de interesarme. Yo necesito entender las cosas, que me emocionen. Por eso rompí con el Jazz durante unos años, pero volví a él por el jazz latino. Vuelvo porque descubro en el jazz latino una especie de energía que me hace volver.

El jazz es la música más aventurada que existe. Porque hay que tener un gran conocimiento musical, una técnica impresionante, y luego hay que tener el valor de improvisar, de que crear, de dejarte llevar, de hacer que las cosas ocurran. Eso es muy bonito. Yo creo que el escritor también hace eso. Hay un momento en el proceso de escritura en que la mano corre por la página, y una frase lleva a otra. Eso, en música, solo lo hace el músico de jazz. El músico de jazz se tira por la ventana sin red, y a veces vuela.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —Ejerciste como crítico cinematográfico.

Fernando Trueba: —Sí, cuando era muy joven, entre los 20 y los 24 años, que dirigí mi primera película. Pero yo ya soñaba con hacer cine. Hacer crítica era una oportunidad de ver cine y que además te pagaran. Alguna vez me han propuesto publicar esas críticas y siempre me he negado. Eran sinceras y apasionadas, pero creo que yo era muy joven y no tienen el nivel para eso. Me gusta mucho leer las críticas de Truffaut y tengo en casa los libros de Mani Farber, de Andreu Sarris, hasta de escritores que ejercieron la crítica como Graham Green, Alberto Moravia o Flayano.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: —¿Cuál es la importancia que tienen los críticos, hasta qué punto pueden llegar a influir?

Fernando Trueba: —Yo creo que estamos en una época muy mala para la crítica, porque la crítica en el sentido creativo de cine, prácticamente, ha desaparecido. Ahora no hay un crítico al que yo siga. Me puede intersar Hoberman o Rosenbaum en Estados Unidos, pero ni siquiera al cien por cien. Me parece que Rosenbaum, en Chicago, es uno de los tíos que está haciendo un trabajo bueno, y tiene más mérito porque lo está haciendo en Estados Unidos, que es un país que vive ensimismado.. En Estados Unidos no miran al mundo, sólo ven cine americano, salvo cuatro gatos en Nueva York y en San Francisco. Rosenbaum lleva adelante una cruzada, hablándole a la gente sobre el cine iraní, cine argentino, el cine taiwanés… Ése es el único crítico que yo leo un poco con interés.

Creo que ahora la crítica es muy superficial. Es crítica de periódico, hecha deprisa y corriendo. Además, los artículos son muy pequeños, sin ningún nivel. No se puede despachar una película en dos líneas.

Para mí la crítica es un acto de amor. Es contagiar tu entusiasmo a los demás. Enseñar a ver algo, o enseñar a leer algo, abrir una ventana para entrar en una obra. A mí eso me ocurría cuando era joven y leía a Truffaut. Lo leía y, de repente, hacía nacer en mí el deseo de ver una película. Eso es maravilloso: cuando te iluminan, cuando te dan pistas, cuando te descubren cosas que te van a hacer feliz, que te van a hacer mejor. Y eso es lo que yo no veo a los críticos de hoy en día.

Creo que la condición básica del crítico es la humildad de reconocer que lo importante es la obra, que el crítico es un intermediario entre la obra y el público. El buen crítico nunca está por encima de lo que habla. Y para una crítica se necesita espacio para contar, desarrollar ideas y relacionarlas.

Enlaces recomendados

- [Vídeo] Entrevista realizada a Fernando Trueba en el Instituto Cervantes de Dublín por Alfonso Fernández Cid.

Interview with Javier Mariscal

Javier Mariscal: “The brain is nothing cold, inert, it is completely sentimental.”

Interview with Javier Mariscal held on the 4th of November 2012, in Damaso Alonso Library, Instituto Cervantes Dublin with the purpose of participating in the ISLA Festival roundtable discussion “Words and Images: Cinema and Literature” by Mark O’Halloran and David Trueba.

Javier Mariscal ( Valencia, 1950) is primarily a creator of images who develops his work through many distinct media and disciplines. Along with his team Estudio Mariscal, founded in 1989, he has worked on numerous international projects (for H&M, The America’s Cup, Camper, among others) as well as a major exhibition of his work at the Design Museum in London “Mariscal Drawing Life”. He has produced two monographs: Mariscal Drawing Life and Sketches. In 2010, along with Fernando Trueba, he directed Chico and Rita, and published the graphic novel of the same name. In 2011 he also published the illustrated novel The Garriris. Chico & Rita was translated into English in 2011.

Vanesa Zafra: Javier, I am very interested in the creative process of graphic designers. How is it for you? Where do you begin the process?

Javier Mariscal: In all design processes, the first thing is to clearly understand the problem you have to solve. In any case, I see my studio as a store that we open in the morning and to which people come saying “I have a communication problem.” For example: “I want to make a record on which Pedrito Hernández will feature, a Cuban rumba singer who lives in New York. He loves all the music of Camarón de la Isla…” Well, from all the information you receive, you ask yourself how you order it. If we’re talking about a guy who is Cuban, sings rumba and the songs of Camarón de la Isla, well, this already has a colour.

Then there are the limits. In this case, you can not say “look, I’m going to make a record that is this big” [gestures widely with his hands]. Because then, in record stores, where they will put it? There are established formats. One can not re-invent anything. The disc will be round. You also have printing limitations and financial restrictions. Perhaps you can not do an inlay card that costs a lot of money.

What are the tools? Typography, colour, illustration, photography…and from here, what you do, as I say, is to process this information and put it in a way that produces a snapshot and if possible, one which touches the heart. Because how do we communicate? We communicate by feelings. The brain is nothing cold, inert, it is completely sentimental.

Vanesa Zafra: Is this the philosophy of your studio? Emotion, humour, fun? How it is structured within a team of many people?

Javier Mariscal: Well, I have no idea. These are questions that I don’t ask myself. This is something more a posteriori, which is itself a very strange word. I do not know. It is a way of establishing things. I will, all my life since I was small, take a stone and say “Look! An airplane!” And then my children, or others will say, “Oh yeah, look! Careful, careful, because I have another one. You are going to crash!” It’s an animalistic way to understand and communicate with each other that we learn when we are very little. I have seen English and Catalan children play without speaking any language, but they understand each other immediately. With a “shun chin chin chu pan bread pa chi cha”. It is the first really potent language that we learn as children. But many kids around the ages of 12 or 15 begin to say: “No no no, this is not an airplane, this is a stone. end of story”.

As a designer, I, and I think the vast majority of other designers, have never stopped working with that system of thought which involves play. This is where one suddenly sees humour. But it is a case of play and more play. Nowadays I have stopped getting insulted, but for a long time people have insulted me. For playing.

Vanesa Zafra: – We are all born creative but we lose this quality when we learn things to become adults. Can we reverse the process?

Javier Mariscal: Being creative is like breathing. Everyone on earth is creative and we are all creative from birth. It is something we have because if not, one would die. It is immediately apparent. You take some shoes like yours that have long laces, so you are creative and you develop a system for removing them and putting them in the easiest way. And this is creativity. I do not understand why some say “you people are so creative”. Well, what about you? Do you think you’re not creative?

Vanesa Zafra: Do you listen to music while you work?

Javier Mariscal: Sometimes, sometimes not. There have been seasons was like a vice. It was impossible to work without music.

Vanesa Zafra: Recommend an album to me.

Javier Mariscal: I would recommend Lágrimas Negras (Black Tears), one of the best albums that has been produced in the last twenty centuries. Because at the time of the Romans there were some very good albums , the problem is they have been lost.

Vanesa Zafra: Something that surprised you, something creative, a work or a movement, perhaps a recent movie…

Javier Mariscal: A movie … Up, for example, was wonderful. Especially the opening section. But of course, it is something obvious. Everyone who has seen it says ” Wow, isn’t the beginning of Up so beautiful, so elegant?” Who knows. Recently I saw a short, a little thing that a friend of mine, Miguel Gallardo, made. Wonderful. There are thousands and thousands of things. Thank God one continually sees these works, other people’s stuff, all this good work, and one remains fascinated. This is what you need to feed your imagination. If not, what else would inspire you?

Vanesa Zafra: And with the internet nowadays, you could be looking through it every day…

Javier Mariscal: Well, I don’t waste much time looking at Internet every day you know? It bores me terribly.

Vanesa Zafra: And what about social networking?

Javier Mariscal: For a while, I was on social networks, it happened suddenly. But now, I don’t know why I haven’t been. I’m not on Facebook. And look, I was posting a picture every day.

Vanesa Zafra: Yes but be a slave to that…

Javier Mariscal: Slave ? No, no, one doesn’t become a slave. It’s done for fun, or not at all.

Recommended Links

- [Video] Interview with Javier Mariscal at the Instituto Cervantes in Dublin by Vanesa Zafra.

Interview with Fernando Trueba

Interview with Fernando Trueba held on the 4th of November 2012 in the Damaso Alonso Library, Instituto Cervantes Dublín, on the occasion of his participation in the roundtable “Words and Images: Cinema and Literature” with Mark O’Halloran and Javier Mariscal for the ISLA Festival 2012.

Fernando Trueba (Madrid , Spain , 1955) is a writer, editor and film director . Between 1974 and 1979 he worked as a film critic for El País and in 1980 he founded the monthly film magazine Casablanca, which he edited and managed for the first two years. In 1992 his film Belle Epoque won 9 Goya Awards , and in 1993 it won the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film. In 1997 he published his book Dicionario del Cine (Dictionary of Cinema) and is editor of the Diccionario del Jazz Latino (Dictionary of Latin Jazz) (1998). In 2010 he directed , with designer Javier Mariscal, the animated film Chico y Rita, which received the Goya for best animated film which was selected for the Academy Awards in the category of Best Animated Film . His most recent film is El Artista y la Modelo (The Artist and the Model) (2012).

Alfonso Fernández Cid: Fernando, I have it engraved in my memory that when you received the Oscar for the film Belle Époque, you said you did not believe in God but in Billy Wilder. Do you still keep that faith?

Fernando Trueba: In Billy Wilder? Of course! For what reason would I ever lose it? There are many directors that I admire and I try to learn from, and he’s one of them. For me, directors such as Renoir, Truffaut, Bresson, Lubitsch , Preston Sturges and many others have been crucial in my development and in my life. But Billy Wilder is part of that group which has become part of me, for better or for worse.

I ‘ve always thought that Billy Wilder is the best screenwriter that ever lived. Well, II think it’s silly to claim that someone is the best director ever, for one day you may think that it is Renoir, and another day it is Lubitsch, and another it’s John Ford, and every day you’re right . Nevertheless, I challenge anyone to show me the proof that there is a better scriptwriter than Billy Wilder. Bring me the scripts with all dialogues, how they are written, structured, and I’m willing to take whatever time necessary to analyze and discuss them, because I’m sure that there is no such scriptwriter better than Billy Wilder. Never!

More than faith, it is a conviction. Faith is believing in something without seeing it. I think beyond seeing and reading, there is a kind of revelation that is felt when you see the masterpieces of Billy Wilder. You keep watching them, and the years go by and you look at them again. You know them by heart and think that you will feel nothing new watching Sunset Boulevard or The Apartment or Double Indemnity or Some Like It Hot. But you see them again and that feeling of infinite admiration for these intelligent, well-made works returns.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: How do you arrive at such a cinematic project as Chico y Rita, in which you managed to involve Bebo Valdes and [Javier] Mariscal?

Fernando Trueba: It came out of friendship. Friendship is one of the biggest incentives in my life, something that is at the source of many things I’ve done. In this case, it has been my friendship with Mariscal. It all started with Calle 54. He produced the artwork for the documentary. Then I started making records and I continued to ask him to design them for me. Because I love what he does and because we understand each other very well. I laugh a lot with him too.

One day he tells me “I’ll die without having done something I would have really loved to do: to make an animated feature film.” And I said “Surely you’ve had a thousand proposals right? Why haven’t you done one yet?” And he said “Yes, but a movie like this is not a question of hours, but of months, years, drawing by hand, bent over a table, and whenever anybody offered me anything, it was for a story I did not like. I will not lose my life, my eyes and my arms to draw a story that I do not like.”

Of course, for me animation is a totally alien world, I had never considered it before. He said to me, “For example, you will not take animation and this kind of stuff seriously. You would never give the time to write a script for an animated film.” He caught me by surprise. In essence, these conversations began the project. One day, in his study, I saw drawings of old Havana. I was overcome with enthusiasm when I saw them, “How beautiful!” I said. “This is what you need to do! This is the movie that I must make! A film in your Havana, Mariscal’s Havana. That would be spectacular!” And so it began. He said: “Yes , but it must have music.” “Man, if its a story in Havana and the Cuban people, it will be difficult for it not to have music.” “Yes, but with lots of music,” he insisted. Then I said, “Why not do a story about musicians.” “Ok, a saxophonist and a singer who fall in love.” I said that was the worst Scorcese movie ever, New York New York, I hated that movie. “Why not a pianist so, and each time he plays the piano, we put in Bebo Valdés”. And so begins a movie, slowly, like everything in life, from a sentence , an image, a conversation. And then one needs to start writing and drawing for years.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: So the journey was a long one.

Fernando Trueba: Yes, first a script is produced and many versions of it are made. Then, to convince people to believe in the project and raise the money needed to do something so expensive, it is necessary to demonstrate the style in which the film would be made. Xavi [Mariscal] then began to draw characters , backgrounds, even maps were created as a demonstration. It took several years to find the people and the money to co-produce the project. Once this is found, we had to to start with storyboards, the characters, the hundreds of animators, drawing for two years. Actually, the process took seven years. What happened was that I, in the meantime, I wrote the screenplay for one movie, produced another couple of them, and I shot in Chile for El baile de la victoria (The Victory Dance). Otherwise, I would have died. There were parts of the production during which I could do nothing but wait: we had already recorded the sound, the music, and planned the camera movement. I just had to wait for the drawings to arrive and check that all was well.

It is very strange, animation. For me, it was like facing a completely new and different world. I have to say I enjoyed it like a child. Except the wait, how long it takes, the patience that one needs. Every time a drawing arrived from Xavi, every time I received a map, it was a joy, a tremendous rush. In fact we are planning two further projects. Chico y Rita has opened many doors for us. We have co-producers in several countries interested in what we are doing next. There’s a story that is very Xavi-esque, based on the characters from Garriris, one of his first comics, and he is working on the script with a screenwriter. As for me , I’m writing another one. We want to make them together. But the first project is more for Xavi, more for his world and and affairs , and the other is a draft of a story I want to tell.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: The great jazz fans always have a love affair with the music. What is your relationship with it?

Fernando Trueba: I have been through many different stages, because I discovered jazz as a teenager through my older brother. And it got the hook in me in a big way. I remember in those early days, when I was 14 , 15, 17, and I really liked Keith Jarrett, Dave Brubeck, McCoy Tyner. After this, there was a time in my life when I distanced myself from jazz, during my college years.

It was the era of free jazz, which was too free for me. It wore me out. It was a kind of music for musicians, too experimental. There is always a moment, in all the arts, when all the isms have been exhausted and a kind of delirium tremens is arrived at: “We will write without commas”, “let’s not paint , let’s put 27 phones on the floor and call it an installation” … At that point, I remove myself. Art, at the point in which communication is severed, no longer interests me. I need to understand things for them to excite me. So I left Jazz for a few years, but I returned to it through Latin jazz. I returned because I discovered a kind of energy in Latin jazz that made me come back.

Jazz is the most adventurous music that exists. Because one must have a wide musical knowledge, outstanding technical abilities, and then one must have the courage to improvise, to create, to let yourself be carried away, to let things happen themselves. That is very beautiful. I think authors also do this. There is a moment in the writing process where the hand moves by its own accord, and one sentence leads to another. This, in music, is only experienced by a jazz musician. A jazz musician will throw himself out the window without a safety net, and sometimes he will fly.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: You worked as a film critic.

Fernando Trueba: Yes, when I was very young, between the ages of 20 and 24, when I directed my first film. But I had already dreamt of making movies. Writing reviews was an opportunity to watch movies and get paid at the same time. Once, it was proposed for me to publish these reviews but I’ve always refused. They were sincere and passionate, but I think I was very young and did not have the capacity for it then. I do enjoy reading the reviews of Truffaut though, and in my house I have books by Manny Farber, Andrew Sarris, even writers who worked as critics such as Graham Greene, Alberto Moravia or Ennio Flaiano.

Alfonso Fernández Cid: What is the importance of critics – to what extent can they have an influence?

Fernando Trueba: I think that it is a very bad period for film criticism at the moment, because criticism, in the creative sense of cinema, has practically disappeared. Nowadays there is not one critic that I follow. Hoberman and Rosenbaum, from the US, interest me, but not entirely. I think Rosenbaum, in Chicago, is one person who is doing a good job, and has more merit still, because he is doing it in the United States, a country that is very self-absorbed…the United States does not look out at the world, but only at American cinema, with the exception of a select few in New York and San Francisco. Rosenbaum is mounting a crusade, telling people about Iranian cinema, Argentine cinema, Taiwanese cinema…he is the only critic I read with even a little interest.

I think that now, criticism has become very superficial. It is newspaper criticism, made hastily and in a hurry. In addition, the articles are very small, with little detail. You can not deal with a movie in a couple of lines.

For me, criticism is an act of love. Your enthusiasm should be contagious to others – to teach how to see something, to teach how to read something, to open a window onto an artistic work. This happened to me when I was young and read Truffaut. I read it and, suddenly, the desire to see a movie arose inside me. This is wonderful – when you become enlightened, when you are given clues, when you discover things that give you joy, when you feel your life is improved. And that is what I do not feel from critics nowadays.

I think the basic condition of the critic is to have the humility to recognize that what matters is the work, that he or she is an intermediary between the work and the public. A good critic is never above what he or she writes about. Criticism needs space for it to be developed, space for ideas to be explained and contextualised.

Recommended Links :

- [Vídeo] Interview with Fernando Trueba at he Instituto Cervantes in Dublin by Alfonso Fernández Cid.

Hoy leemos con | Today we are reading with: Ita Daly, Rafael Gumucio, Maighréad Medbh, Lorenzo Silva.

Para finalizar el Festival Literario ISLA, os ofrecemos unas lecturas en el Café Literario, el 4 de Noviembre a las 12.45.

Para finalizar el Festival Literario ISLA, os ofrecemos unas lecturas en el Café Literario, el 4 de Noviembre a las 12.45.

Última lectura del festival que clausura este festín literario con las voces de estos cuatro escritores que leerán una selección de su obra en su lengua original. Presenta: Megan Specia.

Ita Daly (Drumshanbo, Leitrim, Irlanda) ha publicado cinco novelas, una colección de cuentos y dos libros infantiles. Ha recibido el premio Hennessy Literary Award y el Irish Times Short Story Award. Su obra ha sido traducida al sueco, danés, japonés, italiano y alemán y sus relatos cortos han aparecido en revistas de Irlanda, Inglaterra y Estados Unidos. Uno de sus libros de relatos, The Lady With the Red Shoes, forma parte del plan de estudios de las escuelas de secundaria alemanas.

Rafael Gumucio (Santiago, Chile, 1970) es escritor y profesor de castellano y se licenció en Literatura por la Universidad de Chile. Ha trabajado como periodista en varios diarios. En 1995 publicó el libro de relatos Invierno en la Torre y Memorias Prematuras. Ha publicado también las novelasComedia Nupcial, Los Platos Rotos y Páginas Coloniales. Su última novela es La Deuda (2009). Actualmente es Director del Instituto de Estudios Humorísticos de la Universidad Diego Portales y co-conductor del programa Desde Zero en Radio Zero. Ha recibido el premio Anna Seghers, Alemania, 2002.

Máighréad Medbh (Condado de Limerick, Irlanda) ha publicado cinco libros de poesía y un audiolibro. Fue pionera de la performance poética en Irlanda en los años 90. Su colección más reciente es Twelve Beds for the Dreamer (2010). La obra de Máighréad ha sido publicada en una gran variedad de antologías y ha escrito versiones de poemas gallegos para dos antologías recientes editadas por Manuela Palacios (Universidad de Santiago de Compostela).

Lorenzo Silva (Madrid, España, 1966) ha escrito, entre otras, las novelas La flaqueza del bolcheviqueque ha sido llevada al cine por Manuel Martín Cuenca, y Carta blanca. Ha publicado también libros infantiles y juveniles, además de ensayos. Es especialmente conocido por la serie policíaca protagonizada por los investigadores Bevilacqua y Chamorro, iniciada conEl lejano país de los estanques (Premio Ojo Crítico 1998), y a la que siguió, entre otras, El alquimista impaciente (Premio Nadal 2000). Su último libro es Niños Feroces (2011). Su obra ha sido traducida a numerosos idiomas, como ruso, francés, alemán, italiano o griego.

To close the ISLA Literary Festival, we offer some readings at Café Literario, in November 4th at 12:45.

This literary festival will close with poetry readings by these four writers in their original language. Introduced by: Megan Specia.

(Drumshambo, Co. Leitrim) has published five novels, one collection of short stories and two books for children. She has won two Hennessy Literary Awards and an Irish Times Short Story Award. Her last novel, Unholy Ghosts (1997), was long listed for the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award. Her work has been translated into Swedish, Danish, Japanese, Italian and German and her short stories have appeared in magazines in Ireland, England and America. Her short story collection The Lady With the Red Shoes (1980) is currently on the secondary school curriculum in Germany.

Rafael Gumucio (Santiago, Chile, 1970) has worked as a journalist for many Chilean and Spanish newspapers, as well as the New York Times. In 1995 he published the collection of short stories Invierno en la Torre and Memorias prematuras. He also published the novels Comedia Nupcial, Los Platos Rotos and Páginas Coloniales. His latest novel, La Deuda, was published in 2009. He now works as the director of the Institute for Humour Studies of the University Diego Portales and is co-conductor of Desde Zero at the radio station Zero. He received the Anna Seghers Award in Germany in 2002.

Máighréad Medbh (Co. Limerick) has five published poetry collections and an audio CD. She was a pioneer of performance poetry in Ireland in the nineteen-nineties. Her most recent collection, Twelve Beds for the Dreamer was published in 2010. Máighréad has been published in a wide range of anthologies, and has written versions of Galician poems for two recent anthologies edited by Manuela Palacios of Universidad de Santiago de Compostela.

Lorenzo Silva (Madrid, Spain, 1966) is author of novels such as La Flaqueza del Bolchevique which was adapted for cinema by Manuel Martín Cuenca, and Carta Blanca. He has also published books for children and young adults, as well as essays. He is especially known for the crime series starring detectives Bevilacqua and Chamorro, the series started with El lejano país de los estanques winner of the Ojo Crítico Award in 1998, and was followed by El Alquimista Impaciente winner of the Nadal Award in 2000, the later being adapted to cinema by Patricia Ferreira. His latest book Niños Feroces was published in 2011. His books have been translated into numerous languages such as Russian, French, German, Italian and Greek.

Mesa redonda | Round table discussion: Palabras e imágenes, cine y literatura. (Words and images, cinema and literature)

Comenzamos el último día del Festival Literario ISLA con una discusión literaria que tendrá lugar a las 11:00 en el Café Literario.

Comenzamos el último día del Festival Literario ISLA con una discusión literaria que tendrá lugar a las 11:00 en el Café Literario.

Cine y literatura, novela gráfica o cómo surgen historias narradas en imágenes y/o palabras serán algunos temas de los invitados Javier Mariscal (diseñador), Fernando Trueba (director de cine) y Mark O’Halloran (actor y guionista). Modera: Ciaran Carty.

Javier Mariscal (Valencia, 1950) es ante todo un creador de imágenes que desarrolla su trabajo en todo tipo de soportes y disciplinas. Junto con el equipo del Estudio Mariscal, que fundó en 1989, ha realizado numerosos proyectos internacionales (H&M, America’s Cup, Camper, etc.), además de la exposición sobre su trabajo Mariscal Drawing Life en el Design Museum de Londres y dos publicaciones monográficas: Mariscal Drawing Life y Sketches. En 2010, ha dirigido junto a Fernando Trueba, Chico y Rita y se ha publicado el cómic Chico & Rita. En 2011 ha publicado también el libro ilustrado Los Garriris.Chico & Rita se ha traducido al inglés en 2011, publicándose también en Francia y Países Bajos.