El actor, cineasta y escritor Fernando Fernán-Gómez cumple cien años

El actor, cineasta y escritor Fernando Fernán-Gómez ocupa un lugar de honor en la cultura española y por eso, y como homenaje, durante este enero de 2022 le dedicamos en el canal Vimeo del Instituto Cervantes cuatro sesiones en las que presentaremos «F. F. G. Un retrato» —un corto que le dedicó el crítico y cineasta Jesús García de Dueñas—; dos películas dirigidas por él —su ópera prima, «Manicomio», y «El extraño viaje», una de las obras maestras del cine español—, y «La lengua de las mariposas», en la que podremos disfrutar de una de las más recordadas actuaciones de este gran artista independiente y crítico, completo e irreemplazable. Ciclo «Fernando Fernán-Gómez cumple cien años»: https://vimeo.com/showcase/fernando-fernan-gomez-100

- Programa completo «Fernando Fernán-Gómez cumple cien años» https://vimeo.com/showcase/fernando-fernan-gomez-100

- ▶️7/1 «F. F. G. Un retrato», de Jesús García de Dueñas https://vimeo.com/646435317

- ▶️14/1 «Manicomio», de Fernando Fernán-Gómez y Luis M. Delgado https://vimeo.com/646479891

- ▶️21/1 «El extraño viaje», de Fernando Fernán-Gómez https://vimeo.com/646442848

- ▶️28/1 «La lengua de las mariposas», de José Luis Cuerda https://vimeo.com/646449792

El Instituto Cervantes de Londres obtiene el Certificado ISO 9001 Gestión de Calidad

El Instituto Cervantes de Londres obtiene el Certificado ISO 9001 Gestión de Calidad, que es la norma de gestión de la calidad más importante del mundo. Con esta acreditación se certifica externamente la calidad de nuestros procedimientos.

Conforme a estándares internacionales, se han verificado, entre otros puntos: el gobierno corporativo del centro, la calidad de los procesos, la formación de nuestros profesores, la excelencia en la información al estudiante o usuario, la consistencia de la actividad cultural y de biblioteca, el mantenimiento de las instalaciones y su cumplimiento conforme a normativa local, etc. El informe final, además de hacer constar su opinión satisfactoria, no hace observaciones y no contempla ninguna deficiencia en la calidad.

La obtención del Certificado ISO 9001 Gestión de Calidad es un paso muy relevante para el Instituto Cervantes de Londres y queremos agradecer a todo nuestro equipo haberlo conseguido.

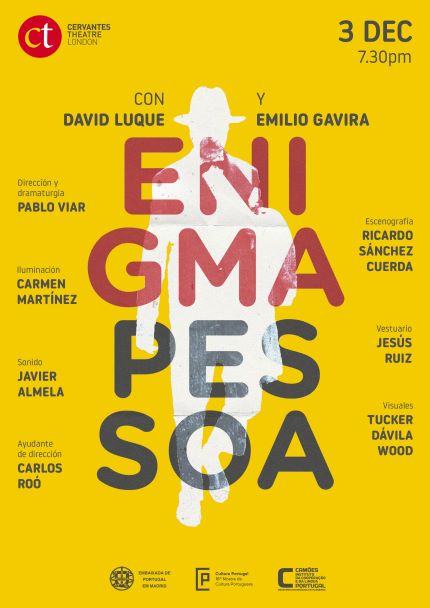

Enigma Pessora, en el Cervantes Theatre

En 1932, envejecido y necesitado, el gran escritor portugués Fernando Pessoa se postula para el empleo de conservador de una pequeña biblioteca-museo en Cascais, no lejos de su adorada Lisboa.

A través de las respuestas al formulario, el poeta recuerda diversas escenas y situaciones reales e imaginarias de su vida y su obra literaria, celosamente guardada en su mítico “baúl lleno de gentes”.

A partir de este revelador episodio, Enigma Pessoa explora de manera poética la fascinante figura del autor de la heteronimia a través de una cuidada selección de materiales literarios y biográficos, desde poemas, textos en prosa y cartas de amor hasta imágenes personales y de los movimientos artísticos de su tiempo.

Su candidatura al puesto fue rechazada y apenas tres años después, Pessoa falleció, solo y enfermo, sin alcanzar la gloria literaria y la profunda admiración de la que su extraordinaria obra y su entrañable persona tan merecidamente disfrutan universalmente hoy.

3 de diciembre – 7:30pm – En español

In 1932, aged and in need, the great Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa applies to a job as a small museum library curator in Cascais, not far from his beloved Lisbon.

As he answers the questionnaire, the poet recollects certain scenes and situations, both real and imaginary of his life and works, zealously kept in his mythical “trunk full of people”.

From this illuminating episode, Enigma Pessoa poetically explores the fascinating figure of the author of heteronymy, through a carefully selected collection of literary and biographical materials, including poems, texts in prose and love letters as well asimages from his private life and the artistic movements of his time.

His application for the job was rejected and barely three years later, Pessoa died, sick and lonely, without having reached the literary glory and the deep admiration his endearing figure and extraordinary oeuvre so deservedly enjoy today.

Special offer for our students at the European Bookshop

We are pleased to announce that our students can benefit from a 10% DISCOUNT at The European Bookshop on coursebooks, literature and more! Simply visit their website and select Instituto Cervantes London (Students) to redeem online: www.europeanbookshop.com/setbooks

nline.

Your discount will be applied automatically. Click & Collect is available.

THE EUROPEAN BOOKSHOP

123 Gloucester Road London SW7 4TE

OPENING HOURS

Mon-Fri 10:00 – 18:30

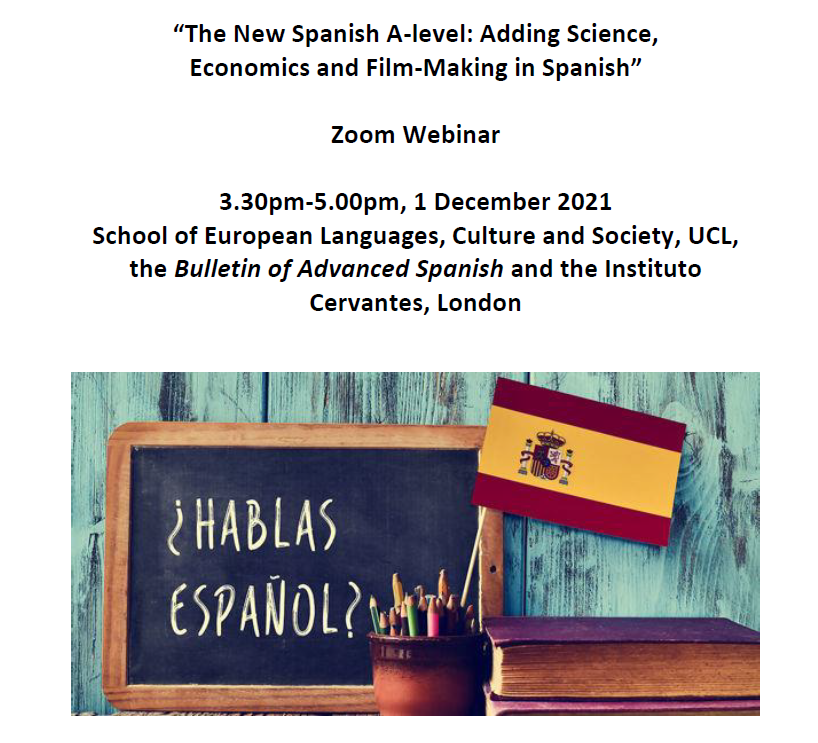

“The New Spanish A-level: Adding Science, Economics and Film-Making in Spanish” (Zoom Webinar)

In this webinar we are seeking to create a new Spanish A-level, which will have three new features:

(i) A new option on “Science and Technology in Spanish”

(ii) A new option on “Business and Economics in Spanish”

(iii) A new option on “Film-making in Spanish”

Our aim is to use these three proposed changes to the curriculum of the Spanish A-level in order to improve and enhance the student’s experience when taking the Spanish A-level, and provide the appropriate framework for studying a language which is truly global in reach and significance. The rationale for these three proposed changes came out of four Opinio surveys that were held in June-July 2021 and co-ordinated by the Bulletin of Advanced

Spanish, and were presented at the Webinar on “Modern Languages: Challenges and Solutions” that was held at University College London on 14 October 2021.

The research carried out in this project has been funded by a HEIF/UKRI grant running from 15 March 2021-14 March 2022. The webinar programme is as follows:

1 DECEMBER 2021: SCHEDULE

3.30-3.50 pm Ignacio Peyró (Director, Cervantes Institute, London),

‘Global Spanish’(talk will be given in Spanish)

3.50-4.10 pm Dr Owen Williams (Post-doctoral Researcher, SELCS, UCL),

‘Film-making in Spanish: An Exemplar’

4.10-4.30 pm Dr Sander Berg (Teacher of Spanish, French and German,

Westminster School) ‘Science and Technology in Spanish:

An Exemplar’

4.30-4.50 pm David Walker (Head of Modern Languages, Kingswood

School), ‘Economics and Business in Spanish: An Exemplar’

4.50-5.00 pm Q & A with the panellists

Convenor Stephen Hart (SELCS, UCL

Aim of this webinar

In this webinar we will be drawing together some ideas on how to improve the experience of students taking the UK Spanish A-level course and exam, while reflecting on the context of Spanish as a truly global language which is spoken by more than 559 million people, of whom more than 460 million are native speakers, making Spanish the language with the second largest population of native speakers in the world. We will look in particular at three proposed innovations in the Spanish A-level, involving the introduction of new options in “Science and Technology in Spanish”,

“Economics and Business in Spanish”, and “Film-making in Spanish” into the A-level syllabus. And we will conclude with an ‘open mike’ roundtable in which you are invited to contribute your opinion, your ideas and your suggestions. This is a free event! All welcome!

How to Register via Eventbrite

https://www.eventbrite.co.uk/e/adding-three-options-to-spanish-a-level-science-businessfilmmaking-

tickets-211064137517

How to attend

Join Zoom Meeting

https://ucl.zoom.us/j/92236503410

Meeting ID: 922 3650 3410

More Information?

If you need more information, please email the convenor, Professor Stephen Hart at Stephen.malcolm.hart@ucl.ac.uk

Jaime Martín: “Toqué música en la calle y me sirvió para dirigir orquestas”

Jaime Martín tiene calle. Por eso desprende un carisma distinto a la hora de dirigir orquestas. Posee la empatía de las aceras, tan ajena a los aislamientos y endiosamientos del podio. Fue flautista de referencia. Hoy, con 56 años, el santanderino es junto a Gustavo Gimeno el director español más internacional: titular de Los Ángeles Chamber Orchestra, la RTE National Symphony de Irlanda, la Gavle en Suecia, que dejará para hacerse cargo a partir de 2022 de la Sinfónica de Melbourne en Australia y principal director invitado de la Orquesta Nacional de España (ONE). Todo el mundo quiere trabajar con él. ¿Por qué…? Lee la entrevista en El País

Richard Kagan: “America’s discovery of Spain was a discovery of itself”

The director of Instituto Cervantes London, Ignacio Peyró, interviews Richard Lauren Kagan, American historian specializing in modern history, at ABC Cultural Spanish newspaper.

Richard L. Kagan is Arthur O. Lovejoy Professor of History at the Johns Hopkins University where he has been a member of the faculty since 1972. A graduate of Columbia University (BA 1965) and Cambridge University (Ph.D. 1968), he is the recipient of many awards, among them grants from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, the Fulbright Association, the Getty Trust, and the National Endowment of the Humanities. In 1997 His Majesty Juan Carlos II honored him with the title of Comendador in the Order of Isabella the Catholic and in 2012 he was elected Corresponding Member of Spain’s Royal Academy of History for his contributions to the history of Spain.

Specializing in the history of early modern Europe, with particular interests in Spain and its empire, Prof. Kagan is the author and/or editor of eleven books as well as numerous articles, essays, and reviews. His recent publications include Spain in America: The Origins of Hispanism in the United States (2002); and a revised edition of Inquisitorial Inquiries: Brief Lives of Secret Jews and Other Heretics (2011). Forthcoming publications revolve principally around his current book, “‘The Spanish Craze:’ The ‘Discovery’ of the Art and Culture of Spain and Spanish America in the United States, ca. 1890- ca. 1930.”

-How did this book come about? Until now there has not been such a systematic and detailed study of the US romance with Spain.

The origins of the book go back to 1992, when I first began to explore changes in the different ways historians in US wrote about the history of Spain. I soon realized that, except for studies of the “black legend”, and its opposite, “the white or pink legend”, much remained to be learned. For reasons connected to my on-going interest in El Greco and the history of art collecting in the USA, this research led me initially to explore the growing interest ca. 1890 in Spanish Golden art, a “ school” (as it was then called) previously denigrated in the US. That interest unleashed the equivalent of artistic gold rush among wealthy American collectors –think Isabella Stewart Gardner, for instance, who led the way for the Havemayers., Frick, Widener, and others, Archer Milton Huntington among them, desperate to snap up choice canvases by Velazquez, Goya, Zurbaran and other artists. Works by El Greco – whose so-called ‘extravagant’ style was perceived a precursor to modern art, were particularly in demand, so much so that one critic likened it to a disease he called “ Elgrecophilitus.”

In any event, I soon discovered that there were other facets in America’s “discovery” of Spain. One, particularly important, was in architecture, which started in late 1880s with the construction of series of skyscrapers and towers modeled after Giralda –first in NY, then California, Chicago and elsewhere, including Cleveland and Kansas City— along with that of large resort hotels built in “ Spanish” style -actually a mish-blend of Mudejar and Spanish plateresque and baroque, with some Mexican elements. The town of St Augustine, Florida, fastening on to its Spanish origins, led the way, others followed suit. Almost simultaneously, in California and other parts of the South West, architects created “mission-style” buildings modeled after the region’s then crumbling Spanish 18th C missions, followed by more elaborate constructions –known as Spanish revival : a blend of Mexican colonial and Spanish baroque – which became so popular that one critic suggested Congress declare it the country’s ‘ national style.

Be that as it may, as I began writing about art collecting and Spanish architecture in the US, I realized that it was tantamount to a fashion trend, a craze —John Singer Sargent, the artist, called it a fever– that quickly spread, Covid-like, nation-wide, and which also spilled over into a fascination with Spanish-themed popular music, Spanish-style clothing – the mantilla and mantón de Manila were all the rage in the 19teens and 20s. It also popped on Hollywood’s Silver screen with a rash of Spanish themed moving pictures (Zorro, for example), and more.

In short, I was looking at something cultural historians in the US had simply overlooked or ignored, and when I asked my good friend, the art historian, Jonathan Brown, whether I should write book on the subject, he answered, tersely “go for it”. Which I did.

-From the Dutch craze to the Japanese craze, there were other «fevers» that conquered America. What was specific about the Spanish craze?

Starting in the decades following America’s Civil War ( 1861-65) –the era Mark Twain called the Gilded Age–, the culture in the US became increasingly cosmopiltan, with new interest in arts and cultures of various parts of the world; an interest, of course, that paralleled the country’s emergence as economic world power. Cosmopolitanism bred ‘crazes’ of various sorts —a Dutch one, another focused on Japan, still others on Ottoman culture, and in the 1930s, Mexico. The Spanish Craze in this sense was just one of many, but in contrast to the others, which were generally quite ephemeral, it proved exceptionally-long lived, spanning the decades from the late 1880s until the start of the depression of the 1930s, save for a brief interruption in the run-up to the war of 1898. Why? One is that, as Walt Whitman, the poet, in 1883 called the “ Spanish element” in our population, the Spanish Craze could be traced to the Spain’s presence in North America, signs of which especially are apparent in Florida, Texas, California and much of the west. These signs were present in place names (states: California, Florida, Colorado, Texas), those of rivers and towns (Los Angeles, El Paso, etc), and even in many state flags —and more signs of same origin could be found in region’s vernacular architecture, starting with the missions. In other words, whoile the Dutch and Japan craze were basically imports, certain aspects of the one for Spain were autocthonous, home-grown, in ways the imports were not. In this sense, America’s discovery of Spain was, in part, a discovery of itself, and this helped to power the craze it describes.

-How was this Spanish seduction possible after centuries of indifference and a war in 98?

“ Forgive and Forget” –this idea, which appeared in the immediate aftermath of the war of 98, helps to explain it. Just as America romanticized and embraced the “ vanishing Indian” in the late 19th C, after 1898, having defeated one remaining imperial rival in the New World, Spain, was able to embrace its arts and culture as never before. The roots of this embrace can be traced back to the romanrticized portrait of “ sunny Spain” that Washington Irving in his Tales of the Alhambra did so much to create. It can also be found in the mid-19th C writings of such widely-read historians such as Prescott, who helped to create the image of Spain as a brave, energetic country who had brought civilization and religion in the guise of Christianity to the Americas, north, central, and south. Today, of course, many observers have a different, far more critical view of Imperial Spain and its presence in the Americas, but in the 19th C that vision of “sturdy Spain” a brave Spain, “seemed to anticipate what Americans thought they were doing in the ‘winning of the west’ –that is, bringing civilization to its native peoples. That idea –Spanish history as a kind precursor to the history of the US– found its way symbolically into the rotunda of the new capitol in the guise of William H Powell’s monumental painting “ Hernando de Soto and Discovery of the Mississippi”, hung there in 1846 ( and still there), part of a series of historical paintings documenting various scenes in the history of the country. The idea: that Spain’s history was part of, integral to US history ,also helps to explain the origins of what later mushroomed into the Spanish Craze.

-A curious feature of American Hispanophilia is that it was cultured –Irving, Huntington- but it was also very popular: cinema, music… And modern. And with a legacy that distinguishes it from the Spanish passions that French or British have felt: its projection in architecture. Could it be that the Americans, somehow, thought they had Spain «at home», because of the Hispanic footprint in its southern part?

Yes : high brow and low brow, the middle as well – the embrujo cut across all social classes. The wealthy bought paintings by the Spanish Old Masters –you can see them today in museums in New York, Boston, Cleveland, Detroit, Toledo, Los Angeles and elsewhere today – and lived in mansions built in the Spanish style. As for working/ middle class, housing developers sold them the idea of living in their own “ castle in Spain”. The idea of such a castle dates back of course to the Middle Ages and French troubadours. One out side New York was called “The Shores of Seville” bungalows built in the same Spanish style and starting the 1920 Sears Rooebuck & Co even fabricated “ home kits” – that the makings of an entire house “marketed as the “Barcelona” or “ Seville,” The idea of Spanish house as a ’ castle’ blended with “oriental” luxury Irving associated with the Alhambra, producing a cocktail that was judged simple yet charming, luxurious as well. So marketed, that cocktail proved a enormous success.

What happened in architecture occurred elsewhere —hispanofilia ran along two somewhat separate tracks. Prescott, an archtypical Boston Brahmin, had a broad popularship – generations read his history of the conquest of Mexico. Irving was even more popular – his romanticized Spain cropped up in several generations of travel writers who depicted Spain as a place where Americans lived in crowded cities could find simplicity, romance, along with scenes of the picturesque in every day life. That Sunny Spain also factored in the literary success of such books as Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona, the 2nd best selling book in 19th C US, which featured kindly friars and idyllic missions where natives found a refuge from nasty anglo-saxons eager to seize their lands. We now know that those missions were not nearly so idyllic as Jackson and another popular, hispanofilic writer, Charles Lummis, represented them to be, but it was that image that copped on the Silver Screen –Hollywood directors relaeased no fewr than four different versions of Romana in the early 20th C along with other movies featuringf alluring Carmen-like Spanish women and dashing “ Spanish” heros such as Zorro who protected women from various nefarious types – often depicted, sad to say, as Mexicans.

Ruinning parallel to all this – -a line of “ academic” or elite hispanism emerged in the 1820s in the classes of George Ticknor’ at Harvard , later in his influential History of Spanish Literature ( 1849), and the work of other hispanists — by the dawn of the 20th C Unamuno described the American school of hispanism the best there is. Integral to this more elite school – and effectively a product of it – was Huntington and his Hispanic Society of America, founded in 1904. Mention is often made of the popular success of Sorolla exhibition Huntington organized there in 1909, but essentially the HSA operated behind closed doors – a museum for “ students,” a library for scholars, a place for learned tertulias — a model followed in Madrid by Guillermo de Osma, founde of the Instituto Valencia de Don Juan.

Interestingly Huntington’s high-brow brand of Hispanism, however, had little in common wuith demand for Spanish language education that “boomed” in the early 20th C. In conjunction with growing interest in “panamericanism,” growing US economic interest in S Anmerica, and the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, enrollments in Spanish languages boomed — instructors of French and Italian complained about the lack of students in their classes, so too did Huntington about interest in “ business” Spanish as opposed to the great works of the Golden Age, but the study of Spanish took root and reflected in Theodore Roosevelt in a visit to madrid in 1914 that it had the makings of a “universal language.” I never thought of TR as much of a prophet,m but in this instance the man who had fought fought Spaniards on Cuba’s San Juan hill was right.

-It seems that, in some way, the US vision of Spain is inevitably linked to what they call the «Latin» world …

For most of the 19th C/ early 20th C as well, for most Anglos and other Americans from northern Europe, the “ Spanish” signified a Spanish speaker– -whether from Iberia, Mexico or other parts of the central/ south America. “Latino,” in other words, or Hispanic. Interestingly, it was in places like New mexico where wealthy ranchers and landowners – the so called ricos – of Mexican origin began to consider themselves “ Spanish” to distinguish themselves from their landless poorer brethren, the braceros, or what anglos in the region called “greasers.” Spain, Spanishness, for these families became a mark of pride– they claimed direct descendance from the conquistadors, and laid claim to Spanish culture. Much the same happened in California — there too Lummis and others, notably the wealthy ranchers, the so called californios of Mexican heritage, seeking to recrate the “old Spanish days” in the guise of festivals, music, even architecture, played up Spain and Spanishness to the detriment of Mexico. Later critics denounced this as racist, and they were riught, but here it is important to remember that blanket terms such as ‘ latino’ as used today tends to erase the divisions that once permeated the Hispanic population in the US

-Paul Fussell affirms that the United States was made by embracing the heritage of those who came to the East Coast (the Mayflower, to understand us) and denying the Hispanic. Has that perception been changing?

For the last 20, perhaps 30 years, scholars have challenged the idea – basically it dates back to such 19th C Harvard-based historians as George Bancroft – that the US had its origins in New England. As I argue in the book, aready in the 19th C historians such as Thomas Buckingham Smiuthg took issue with Bancroft, so too did -early 20th C scholars such as Herbert Bolton and his disciplines, notably David Weber whose work on the “borderlands” – roughly much of southwest – underscored the influence of Mexican-cum-Spanish influence on that region’s economy and society. Even so, we still have much to learn about the history of what Whitman termed the “ Spanish element in our nationality” along with the varied contributions of Spain to the history of the US, even though there is an effort afoot to raise the profile of Bernardo de Galvez, who opened a second, western front v the British in the US war of Independence has yet to achieve the stature of the Marquis de Lafayette, nor do school children learn much about other Spanish contributions to the victory of the colonies in that conflict. Yet I am optimistic – the rewriting of US history is well underway. The Mayflower will not sink, but the country’s Hispanic heritage, as Whitman predicted, is coming increasingly to the fore, pushed, in part, by the on-going increase in the country’s population of Latino – or Hispanic – background.

Formación de profesores de español (ELE)

El Instituto Cervantes de Londres organiza los siguientes cursos de formación de profesores:

Diseño de secuencias didácticas y presentación de contenidos (10 horas) – En línea

- 6 de octubre – 3 noviembre

- 17 noviembre – 15 diciembre

- Descripción del curso

Introducción a la enseñanza de español (10 horas) – En línea

- 2 y 3 de octubre

- Descripción del curso

Cómo preparar clases a distancia (10 horas) – En línea

- 5 octubre – 2 noviembre

- 16 noviembre – 14 diciembre

- Descripción del curso

Curso de formación para profesores de ELE para niños – En línea

- 9 octubre – 11 diciembre

- Descripción del curso

Curso de formación para profesores de ELE de adolescentes: preparadores de GCSE y A LEVEL de español – En línea

- 7 octubre – 9 diciembre

- Descripción del curso

Curso de gramática para profesores de ELE – En línea

- 6 octubre – 8 diciembre

- Descripción del curso

Cursos para preparadores y examinadores de DELE – En línea

- Nivel A1 – A2: £150 (6 septiembre – 3 octubre) / (8 noviembre – 5 diciembre)

- Nivel B1 – B2: £150 (4 – 31 octubre)

- Nivel C1 – C2: £160 (8 noviembre – 5 diciembre)

- DELE Escolar Nivel A2/B1: £140 (4 – 31 octubre)

- Descripción de los cursos

Matrícula

Para matricularte, descarga este formulario y envíalo con tus datos y copia de la transferencia realizada a cenlon@cervantes.es y te enviaremos la confirmación de la matrícula.

El plazo de matrícula se cierra 24 horas antes del comienzo del curso. En el caso de que se reciban solicitudes una vez cerrado el plazo y solo si hay plazas disponibles, se podría tramitar la matrícula pero no se asegura el acceso del alumno a la primera sesión del curso.

Free Onsite Spanish Beginners Course with Trainee Teachers

This summer we are offering a free face-to-face intensive A11 beginners 25 hour course. All teachers are native speakers and will be monitored by Instituto Cervantes academic staff.

When? Monday to Friday, from 12th to 23rd of July.

What time? 10.00 – 12.30

Where? At our premises in Devereux Court

How much? The course will have an administrative fee of £25 which will be refunded completely if the student attends 80% of the sessions (8 out of 10).

Due to its popularity, we recommend enrolling ASAP by writing to cenlon@cervantes.es or calling 020 7201 0750.

«The secret to being a good translator is to work really hard at acquiring the necessary skills»

Ahead of the publication of THE PENGUIN BOOK OF SPANISH SHORT STORIES, edited by highly revered Margaret Jull Costa on June 24th, by Penguin Classics, we interview her in our blog.

This wonderful anthology brings together over 50 stories from across the Spanish canon. The list of the contributors, many of which have never before been translated into English, includes giants of Spanish literary culture, from Emilia Pardo Bazán and Leopoldo Alas, through Mercè Rodoreda and Manuel Rivas, to Ana Maria Matute and Javier Marías.

This exciting new collection celebrates the richness and variety of the Spanish short story, how was the editing process?

MJC: Well, as you can imagine, it involved a lot of reading, but that was such a pleasure, and led me to making lots of discoveries. The hardest part was having to leave some stories or authors out, but that is the nature of anthologies.

The book includes authors from the nineteenth century to the present day, could you tell us some insights about your selection?

MJC: As well as including all periods from the nineteenth century to now, I wanted the stories to be as varied as possible, some funny, some tragic, some fantastical, some pure realism, etc. and covering as wide a range of human experience as possible too.

It features over fifty stories, what can the audience expect to see?

MJC: I hope they’ll get a real idea of the breadth and variety of Spanish writing and will be introduced to writers they will never have heard of and might well want to read more of.

Which authors are favourites for you?

MJC: My main criterion was only to include stories I loved, so in that sense, they are all favourites!

Which author do you consider a hidden gem for the British public?

Again, there are many candidates, especially among the older women writers – Esther Tusquets, Carmen Martín Gaite, Mercè Rodoreda, Rosa Chacel, Ana María Matute – who tend to be overlooked (a) because they’re women and (b) because they’re dead.

You are a revered translator, in your opinion what is the secret to be a good translator?

MJC: I’m not sure I am ‘revered’! But I am, I hope, respected. And the secret to being a good translator is, as it is for most professions, to work really hard at acquiring the necessary skills. For a translator those key skills are being a very good reader, sensitive to register and tone and voice, and having a real passion for language, your own and the languages you translate from, and a delight in using your own language to its full potential. Oh, and a keen sense of curiosity, always wanting to learn more. Learning a language is a never-ending journey.

You earned an undergraduate degree in Spanish and Portuguese from the University of Bristol, why did you decide to study Spanish at that time?

MJC: I had spent time in Spain when I was younger, between the ages of eighteen and twenty-one, and pretty much taught myself Spanish. Then, when I was twenty-three, I decided I wanted to go to university to study language and literature, so I studied part-time for my Spanish A-Level and got a place at Bristol.