Jaime Martín: “Toqué música en la calle y me sirvió para dirigir orquestas”

Jaime Martín tiene calle. Por eso desprende un carisma distinto a la hora de dirigir orquestas. Posee la empatía de las aceras, tan ajena a los aislamientos y endiosamientos del podio. Fue flautista de referencia. Hoy, con 56 años, el santanderino es junto a Gustavo Gimeno el director español más internacional: titular de Los Ángeles Chamber Orchestra, la RTE National Symphony de Irlanda, la Gavle en Suecia, que dejará para hacerse cargo a partir de 2022 de la Sinfónica de Melbourne en Australia y principal director invitado de la Orquesta Nacional de España (ONE). Todo el mundo quiere trabajar con él. ¿Por qué…? Lee la entrevista en El País

Richard Kagan: “America’s discovery of Spain was a discovery of itself”

The director of Instituto Cervantes London, Ignacio Peyró, interviews Richard Lauren Kagan, American historian specializing in modern history, at ABC Cultural Spanish newspaper.

Richard L. Kagan is Arthur O. Lovejoy Professor of History at the Johns Hopkins University where he has been a member of the faculty since 1972. A graduate of Columbia University (BA 1965) and Cambridge University (Ph.D. 1968), he is the recipient of many awards, among them grants from the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, the Fulbright Association, the Getty Trust, and the National Endowment of the Humanities. In 1997 His Majesty Juan Carlos II honored him with the title of Comendador in the Order of Isabella the Catholic and in 2012 he was elected Corresponding Member of Spain’s Royal Academy of History for his contributions to the history of Spain.

Specializing in the history of early modern Europe, with particular interests in Spain and its empire, Prof. Kagan is the author and/or editor of eleven books as well as numerous articles, essays, and reviews. His recent publications include Spain in America: The Origins of Hispanism in the United States (2002); and a revised edition of Inquisitorial Inquiries: Brief Lives of Secret Jews and Other Heretics (2011). Forthcoming publications revolve principally around his current book, “‘The Spanish Craze:’ The ‘Discovery’ of the Art and Culture of Spain and Spanish America in the United States, ca. 1890- ca. 1930.”

-How did this book come about? Until now there has not been such a systematic and detailed study of the US romance with Spain.

The origins of the book go back to 1992, when I first began to explore changes in the different ways historians in US wrote about the history of Spain. I soon realized that, except for studies of the “black legend”, and its opposite, “the white or pink legend”, much remained to be learned. For reasons connected to my on-going interest in El Greco and the history of art collecting in the USA, this research led me initially to explore the growing interest ca. 1890 in Spanish Golden art, a “ school” (as it was then called) previously denigrated in the US. That interest unleashed the equivalent of artistic gold rush among wealthy American collectors –think Isabella Stewart Gardner, for instance, who led the way for the Havemayers., Frick, Widener, and others, Archer Milton Huntington among them, desperate to snap up choice canvases by Velazquez, Goya, Zurbaran and other artists. Works by El Greco – whose so-called ‘extravagant’ style was perceived a precursor to modern art, were particularly in demand, so much so that one critic likened it to a disease he called “ Elgrecophilitus.”

In any event, I soon discovered that there were other facets in America’s “discovery” of Spain. One, particularly important, was in architecture, which started in late 1880s with the construction of series of skyscrapers and towers modeled after Giralda –first in NY, then California, Chicago and elsewhere, including Cleveland and Kansas City— along with that of large resort hotels built in “ Spanish” style -actually a mish-blend of Mudejar and Spanish plateresque and baroque, with some Mexican elements. The town of St Augustine, Florida, fastening on to its Spanish origins, led the way, others followed suit. Almost simultaneously, in California and other parts of the South West, architects created “mission-style” buildings modeled after the region’s then crumbling Spanish 18th C missions, followed by more elaborate constructions –known as Spanish revival : a blend of Mexican colonial and Spanish baroque – which became so popular that one critic suggested Congress declare it the country’s ‘ national style.

Be that as it may, as I began writing about art collecting and Spanish architecture in the US, I realized that it was tantamount to a fashion trend, a craze —John Singer Sargent, the artist, called it a fever– that quickly spread, Covid-like, nation-wide, and which also spilled over into a fascination with Spanish-themed popular music, Spanish-style clothing – the mantilla and mantón de Manila were all the rage in the 19teens and 20s. It also popped on Hollywood’s Silver screen with a rash of Spanish themed moving pictures (Zorro, for example), and more.

In short, I was looking at something cultural historians in the US had simply overlooked or ignored, and when I asked my good friend, the art historian, Jonathan Brown, whether I should write book on the subject, he answered, tersely “go for it”. Which I did.

-From the Dutch craze to the Japanese craze, there were other «fevers» that conquered America. What was specific about the Spanish craze?

Starting in the decades following America’s Civil War ( 1861-65) –the era Mark Twain called the Gilded Age–, the culture in the US became increasingly cosmopiltan, with new interest in arts and cultures of various parts of the world; an interest, of course, that paralleled the country’s emergence as economic world power. Cosmopolitanism bred ‘crazes’ of various sorts —a Dutch one, another focused on Japan, still others on Ottoman culture, and in the 1930s, Mexico. The Spanish Craze in this sense was just one of many, but in contrast to the others, which were generally quite ephemeral, it proved exceptionally-long lived, spanning the decades from the late 1880s until the start of the depression of the 1930s, save for a brief interruption in the run-up to the war of 1898. Why? One is that, as Walt Whitman, the poet, in 1883 called the “ Spanish element” in our population, the Spanish Craze could be traced to the Spain’s presence in North America, signs of which especially are apparent in Florida, Texas, California and much of the west. These signs were present in place names (states: California, Florida, Colorado, Texas), those of rivers and towns (Los Angeles, El Paso, etc), and even in many state flags —and more signs of same origin could be found in region’s vernacular architecture, starting with the missions. In other words, whoile the Dutch and Japan craze were basically imports, certain aspects of the one for Spain were autocthonous, home-grown, in ways the imports were not. In this sense, America’s discovery of Spain was, in part, a discovery of itself, and this helped to power the craze it describes.

-How was this Spanish seduction possible after centuries of indifference and a war in 98?

“ Forgive and Forget” –this idea, which appeared in the immediate aftermath of the war of 98, helps to explain it. Just as America romanticized and embraced the “ vanishing Indian” in the late 19th C, after 1898, having defeated one remaining imperial rival in the New World, Spain, was able to embrace its arts and culture as never before. The roots of this embrace can be traced back to the romanrticized portrait of “ sunny Spain” that Washington Irving in his Tales of the Alhambra did so much to create. It can also be found in the mid-19th C writings of such widely-read historians such as Prescott, who helped to create the image of Spain as a brave, energetic country who had brought civilization and religion in the guise of Christianity to the Americas, north, central, and south. Today, of course, many observers have a different, far more critical view of Imperial Spain and its presence in the Americas, but in the 19th C that vision of “sturdy Spain” a brave Spain, “seemed to anticipate what Americans thought they were doing in the ‘winning of the west’ –that is, bringing civilization to its native peoples. That idea –Spanish history as a kind precursor to the history of the US– found its way symbolically into the rotunda of the new capitol in the guise of William H Powell’s monumental painting “ Hernando de Soto and Discovery of the Mississippi”, hung there in 1846 ( and still there), part of a series of historical paintings documenting various scenes in the history of the country. The idea: that Spain’s history was part of, integral to US history ,also helps to explain the origins of what later mushroomed into the Spanish Craze.

-A curious feature of American Hispanophilia is that it was cultured –Irving, Huntington- but it was also very popular: cinema, music… And modern. And with a legacy that distinguishes it from the Spanish passions that French or British have felt: its projection in architecture. Could it be that the Americans, somehow, thought they had Spain «at home», because of the Hispanic footprint in its southern part?

Yes : high brow and low brow, the middle as well – the embrujo cut across all social classes. The wealthy bought paintings by the Spanish Old Masters –you can see them today in museums in New York, Boston, Cleveland, Detroit, Toledo, Los Angeles and elsewhere today – and lived in mansions built in the Spanish style. As for working/ middle class, housing developers sold them the idea of living in their own “ castle in Spain”. The idea of such a castle dates back of course to the Middle Ages and French troubadours. One out side New York was called “The Shores of Seville” bungalows built in the same Spanish style and starting the 1920 Sears Rooebuck & Co even fabricated “ home kits” – that the makings of an entire house “marketed as the “Barcelona” or “ Seville,” The idea of Spanish house as a ’ castle’ blended with “oriental” luxury Irving associated with the Alhambra, producing a cocktail that was judged simple yet charming, luxurious as well. So marketed, that cocktail proved a enormous success.

What happened in architecture occurred elsewhere —hispanofilia ran along two somewhat separate tracks. Prescott, an archtypical Boston Brahmin, had a broad popularship – generations read his history of the conquest of Mexico. Irving was even more popular – his romanticized Spain cropped up in several generations of travel writers who depicted Spain as a place where Americans lived in crowded cities could find simplicity, romance, along with scenes of the picturesque in every day life. That Sunny Spain also factored in the literary success of such books as Helen Hunt Jackson’s Ramona, the 2nd best selling book in 19th C US, which featured kindly friars and idyllic missions where natives found a refuge from nasty anglo-saxons eager to seize their lands. We now know that those missions were not nearly so idyllic as Jackson and another popular, hispanofilic writer, Charles Lummis, represented them to be, but it was that image that copped on the Silver Screen –Hollywood directors relaeased no fewr than four different versions of Romana in the early 20th C along with other movies featuringf alluring Carmen-like Spanish women and dashing “ Spanish” heros such as Zorro who protected women from various nefarious types – often depicted, sad to say, as Mexicans.

Ruinning parallel to all this – -a line of “ academic” or elite hispanism emerged in the 1820s in the classes of George Ticknor’ at Harvard , later in his influential History of Spanish Literature ( 1849), and the work of other hispanists — by the dawn of the 20th C Unamuno described the American school of hispanism the best there is. Integral to this more elite school – and effectively a product of it – was Huntington and his Hispanic Society of America, founded in 1904. Mention is often made of the popular success of Sorolla exhibition Huntington organized there in 1909, but essentially the HSA operated behind closed doors – a museum for “ students,” a library for scholars, a place for learned tertulias — a model followed in Madrid by Guillermo de Osma, founde of the Instituto Valencia de Don Juan.

Interestingly Huntington’s high-brow brand of Hispanism, however, had little in common wuith demand for Spanish language education that “boomed” in the early 20th C. In conjunction with growing interest in “panamericanism,” growing US economic interest in S Anmerica, and the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, enrollments in Spanish languages boomed — instructors of French and Italian complained about the lack of students in their classes, so too did Huntington about interest in “ business” Spanish as opposed to the great works of the Golden Age, but the study of Spanish took root and reflected in Theodore Roosevelt in a visit to madrid in 1914 that it had the makings of a “universal language.” I never thought of TR as much of a prophet,m but in this instance the man who had fought fought Spaniards on Cuba’s San Juan hill was right.

-It seems that, in some way, the US vision of Spain is inevitably linked to what they call the «Latin» world …

For most of the 19th C/ early 20th C as well, for most Anglos and other Americans from northern Europe, the “ Spanish” signified a Spanish speaker– -whether from Iberia, Mexico or other parts of the central/ south America. “Latino,” in other words, or Hispanic. Interestingly, it was in places like New mexico where wealthy ranchers and landowners – the so called ricos – of Mexican origin began to consider themselves “ Spanish” to distinguish themselves from their landless poorer brethren, the braceros, or what anglos in the region called “greasers.” Spain, Spanishness, for these families became a mark of pride– they claimed direct descendance from the conquistadors, and laid claim to Spanish culture. Much the same happened in California — there too Lummis and others, notably the wealthy ranchers, the so called californios of Mexican heritage, seeking to recrate the “old Spanish days” in the guise of festivals, music, even architecture, played up Spain and Spanishness to the detriment of Mexico. Later critics denounced this as racist, and they were riught, but here it is important to remember that blanket terms such as ‘ latino’ as used today tends to erase the divisions that once permeated the Hispanic population in the US

-Paul Fussell affirms that the United States was made by embracing the heritage of those who came to the East Coast (the Mayflower, to understand us) and denying the Hispanic. Has that perception been changing?

For the last 20, perhaps 30 years, scholars have challenged the idea – basically it dates back to such 19th C Harvard-based historians as George Bancroft – that the US had its origins in New England. As I argue in the book, aready in the 19th C historians such as Thomas Buckingham Smiuthg took issue with Bancroft, so too did -early 20th C scholars such as Herbert Bolton and his disciplines, notably David Weber whose work on the “borderlands” – roughly much of southwest – underscored the influence of Mexican-cum-Spanish influence on that region’s economy and society. Even so, we still have much to learn about the history of what Whitman termed the “ Spanish element in our nationality” along with the varied contributions of Spain to the history of the US, even though there is an effort afoot to raise the profile of Bernardo de Galvez, who opened a second, western front v the British in the US war of Independence has yet to achieve the stature of the Marquis de Lafayette, nor do school children learn much about other Spanish contributions to the victory of the colonies in that conflict. Yet I am optimistic – the rewriting of US history is well underway. The Mayflower will not sink, but the country’s Hispanic heritage, as Whitman predicted, is coming increasingly to the fore, pushed, in part, by the on-going increase in the country’s population of Latino – or Hispanic – background.

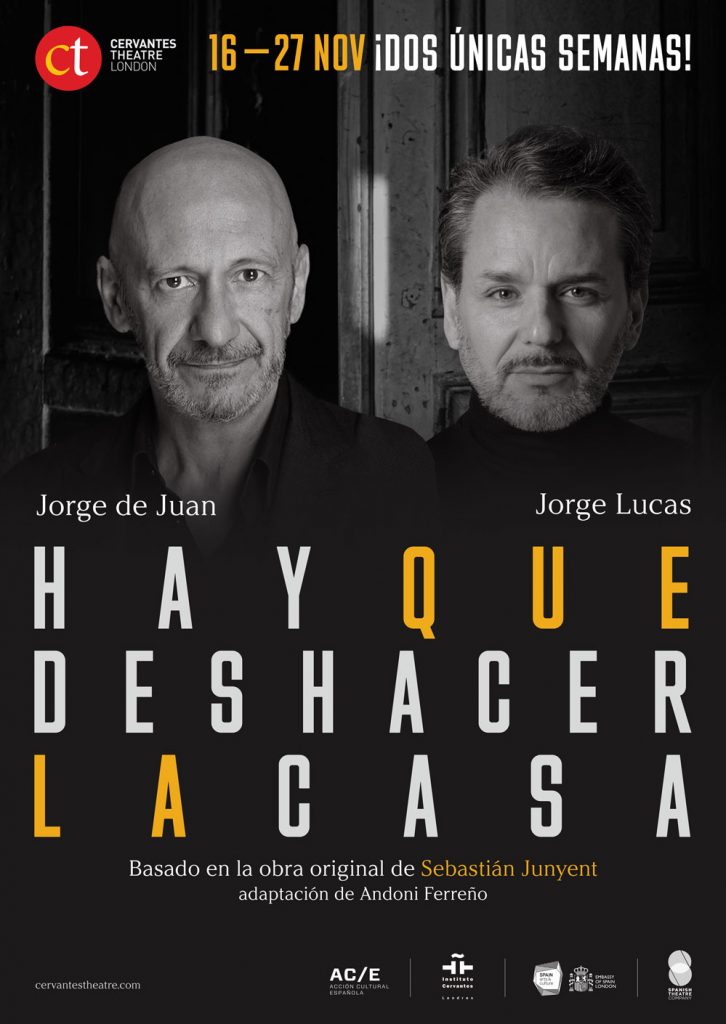

‘Hay que deshacer la casa’, la obra con la que el Cervantes Theatre celebra su quinto aniversario

El Cervantes Theatre de Londres celebra su quinto aniversario con la obra ‘Hay que deshacer la casa’, basadoaen la obra original de Sebastián Junyent, adaptación de Andoni Ferreño.

Dos hermanos –Álvaro y Cosme- separados por la distancia los enfrentamientos tienen que verse, inevitablemente, cara a cara. Uno abandonó la casa familiar para instalarse en París. Los padres quedaron al cuidado del otro, en una pequeña ciudad de provincias. El inevitable reencuentro se produce tras el fallecimiento de los padres. Deben repartirse la herencia en el domicilio familiar. Con cada objeto surge un recuerdo, con cada lote un reproche o una justificación.

El deseo de terminar rápidamente con el tenso reencuentro les lleva a iniciar una disparatada partida de cartas, jugándose con ella los lotes. La casa queda levantada, pero la relación fraternal no vuelve a ser la misma tras la catarsis, a ratos divertida, a ratos dramática y siempre emocionante

The Cervantes Theatre celebrates its fifth anniversary with the play ‘Hay que deshacer la casa’, based in the original play by Sebastián Junyent, with an adaptation byAndoni Ferreño.

Two brothers – Alvaro and Cosme, estranged from each other by distance and conflict, unavoidably have to meet face to face. One brother left the family home to go to live in Paris. The other brother was left to care for their parents in a small regional city. The inevitable reencounter takes place after the parents’ death.

They must divide the inheritance at the family home. Every object brings about a memory, every share a rebuke or a vindication.

Their desire to finish this tense reunion quickly makes them start a foolish game of cards with the inheritance as a prize. The house gets sorted but the fraternal relationship will not be the same. This cathartic interaction is sometimes funny, sometimes dramatic but above all touching.

Tickets: Cervantes Theatre

«Es muy importante la infancia que tuve porque tuve el privilegio de crecer rodeada de animales en el campo»

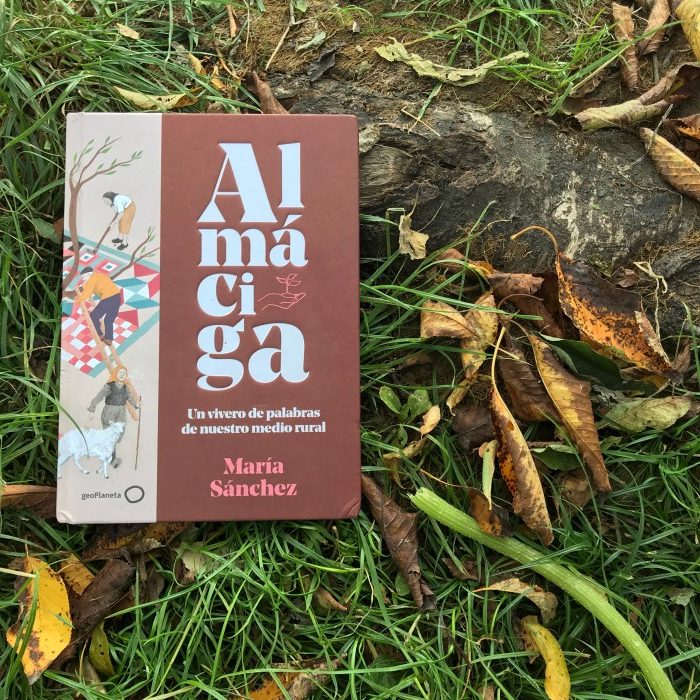

Entrevistamos a la escritora y veterinaria María Sánchez con motivo de su participación en la London Spanish Book & Zine Fair el próximo martes, 19 de octubre. Sánchez trabaja con razas autóctonas en peligro de extinción, defendiendo otras formas de producción y de relación con la tierra como la agroecología, el pastoreo y la ganadería extensiva.

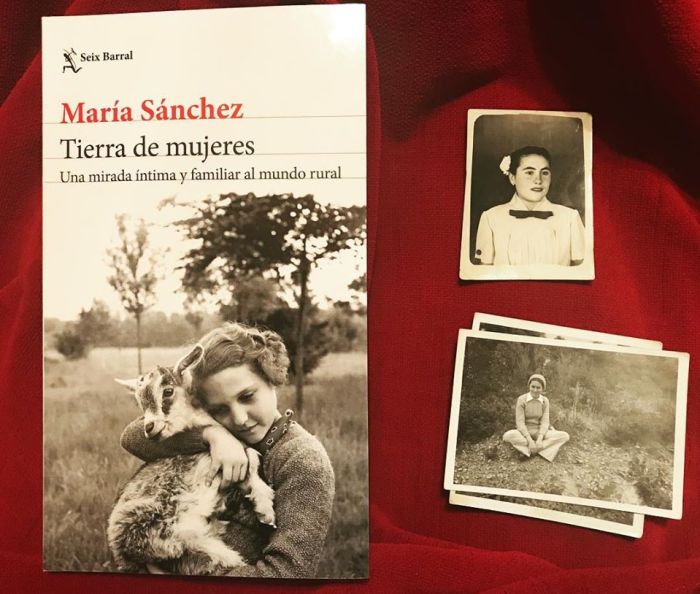

En la feria, Sánchez hablará de Almáciga (Geoplaneta, 2020), un pequeño vivero de palabras del medio rural de las diferentes lenguas de nuestro territorio que sigue vivo y creciendo en formato virtual. Además, la traducción al inglés de su novela Tierra de mujeres, una mirada íntima y familiar al mundo rural, será publicada en mayo de 2022 por University Trinity Press.

En la actualidad, Sánchez participa en una residencia de artistas en Villa Waldberta, Alemania, invitada por el Instituto Cervantes de Múnich, junto a la escritora gallega Albad Cid y el escritor asturiano Xuan Bello.

¿Qué supone para ti participar en la London Spanish Book & Zine Fair?

Algo nuevo y también una oportunidad, porque la realidad es que no he tenido ese contacto con Londres, ni con el inglés, ni con mi escritura ni con mis libros. He tenido traducidas algunas cartas que mando a la plataforma Tiny Letter y el año que viene saldrá Tierra de mujeres, pero en Estados Unidos. Pero con Reino Unido no he tenido ese vínculo y me hace ilusión porque muchos de mis escritores favoritos escriben en esta lengua. Es una lengua que leo mucho y a la que estoy muy unida, así que esta oportunidad me hace bastante ilusión.

Tierra de mujeres saldrá en mayo del año que viene en una editorial que se llama Trinity University Press, donde también publican autores como Rebecca Solnit. Y además, son libros que están muy ligados a la tierra, por ejemplo: a comunidades indígenas, a ganadería extensiva y al tema de colonialismo, entre otros. Es una editorial con la que siento que tenemos muchas cosas en común. Hay mucha afinidad también con el traductor, Curtis Bauer, con unas conversaciones muy interesantes porque él también es un poeta y un escritor de la naturaleza y de la tierra. Están surgiendo también muchas ideas de colaboración, porque está traduciendo también algunos artículos míos para alguna revista con esta temática en Estados Unidos.

¿Y qué te inspira para hacer esta mirada tan íntima y familiar?

Creo que no podría escribir otra cosa, porque al final es lo que me mueve, lo que me rodea, de dónde vengo, el campo, la naturaleza, los vínculos, los animales, los árboles, las relaciones de simbiosis y de apoyo mutuo que se dan en la naturaleza. Creo que hay infinidad de historias y de vínculos y de cosas por contar. Creo que también es muy importante la infancia que tuve porque tuve el privilegio de crecer rodeada de animales en el campo. Y esa, era, y sigue siendo mi vida. Sigo trabajando con el campo y con razas autóctonas en peligro de extinción en España. Creo que es algo que debemos cuidar y conservar, porque para mí es muy importante darlo a conocer, porque muchas de estas cosas no se protegen y no se valoran porque simplemente no se conocen. Si puedo servir de altavoz o de contadora de estas historias, esto para mí, es un regalo.

¿Actualmente ejerces de veterinaria o estás centrada en la escritura?

Ejerzo los dos. Estos meses a Alemania me he traído cosas para hacer, porque veterinaria no es solo un trabajo de campo, hay muchísimo trabajo de oficina, de ordenador y científico. Trabajo a nivel nacional, por ejemplo: en La Palma, con la cabra Palmera; en Extremadura, con la gallina extremeña azul; en Andalucía, con la cabra payoya y la blanca andaluza. Yo trabajo en diferentes comunidades, con diferentes razas. En Galicia, donde resido, todavía no tengo esa colaboración, pero espero que en un futuro pueda tener un proyecto agroecológico, y por supuesto, quiero que esté presente alguna raza autóctona de la tierra. Ahora, La idea para estos meses de residencia es dedicar todo el tiempo que pueda a leer y a la escritura. Me levanto temprano para dejar cosas del trabajo hechas y poder tener tiempo para lo demás.

¿Cómo surge la oportunidad de asistir a la residencia de artistas Villa Waldberta en Alemania?

Me la proponen desde el Instituto Cervantes de Múnich, yo nunca he estado en una residencia de escritura y en Tierra de mujeres cuento que me doy cuenta de que siempre escribo cansada. Ahora ya no tengo ese trabajo tan bestia de salir al campo todas las semanas, porque al ser autónoma me organizo la agenda, concentro esas salidas en uno o dos meses del año y no estoy en la misma situación que cuando escribí este libro. Necesitaba probar la experiencia, y te lo voy a decir tal cual, de levantarme y decir: hoy solo me tengo que dedicar a escribir, no hay otras prioridades, no voy a escribir por la noche, no voy a escribir por la tarde, no voy a escribir en mis ratos libres. Necesitaba probar la experiencia. A lo mejor descubro que necesito una época del año, un mes o una semana, en la que necesito desconectar totalmente de ese trabajo de veterinaria. O a lo mejor descubro que no, que necesito ese trabajo, ese con contacto constante, no desaparecer, aunque sea un periodo mínimo de tiempo. Me siento tan privilegiada de vivir esta experiencia. No sé. Para mí era una prueba y una experiencia totalmente nueva. Encima, tengo la suerte de hacerlo aquí, en Villa Waldberta, que aquí estuvo Thomas Mann; tengo cerca el lago que menciona T. S. Eliot en su poema. Todavía no me creo tener esa oportunidad y me siento súper agradecida al Instituto Cervantes por pensar en mí y hacer posible esta residencia. No sé que saldrá de aquí, pero sí es verdad que desde que llegué me vienen muchas ideas, es como si mi cabeza no dejara de tramar y pensar. Creo que este lugar está siendo maravilloso para eso.

¿Y cómo vives la erupción volcánica en La Palma, cómo te ha afectado y cómo se puede ayudar?

Yo trabajo a distancia con la cabra palmera, que es una cabra muy peculiar, autóctona, en peligro de extinción, que sólo está en esta isla. Y desgraciadamente, estamos pasando una semana horrible porque muchos ganaderos y pastores elaboran el queso palmero, una denominación de origen protegida y un alimento de alto valor ambiental y de calidad, porque la leche de cabra palmera es una de las razas que tiene mayor porcentaje de proteína de Europa y del mundo. La mayoría de los quesos se elaboran de forma artesana y se sigue haciendo la técnica de ahumado que se hacia antiguamente. Hemos visto como muchos ganaderos han tenido que desalojar a sus cabras. Han visto que los lugares donde pastorean o donde vivían ya no están. Han perdido una vida, un hogar y una forma de unión al territorio. Y está siendo muy doloroso porque lamentablemente nos estamos encontrando con algunos medios y periodistas que se están acercando solo desde el morbo y desde los titulares que no cuentan la realidad y que juegan con el dolor.

Están siendo unos días agridulces. Por eso desde la asociación se lanzó una campaña para recaudar fondos, no solo para los ganaderos de cabra palmera, sino para toda la ganadería de la isla, para comprar enseres y cosas que hagan falta. Y con el Cabildo se está también comprando alimentación, porque estas cabras salen a pastorear y debido a la erupción y a la ceniza, el pastoreo no está siendo posible.. Ya llevamos más de 7.000 euros recaudados y desde la asociación están muy agradecidos. Hablo todos los días con los compañeros de la asociación y da mucha pena. Es muy doloroso, hay mucho desánimo, muchísima incertidumbre porque el volcán sigue y no se sabe las consecuencias que va a traer. Aunque la gente done lo que cuesta un café, ya podemos ayudar con algo. Invito a que la gente la apoye, porque además ayudando preservamos saberes, un territorio y un vínculo muy especial entre animales y personas.

Vivimos en un mundo acelerado y con prisas, pero encuentras tiempo para detalles como la camisa con hojitas del peral que plantó tu abuelo cuando naciste y del tilo de tu familia. ¿Qué supone para ti? ¿Son homenajes y/o agradecimientos a la familia y a la naturaleza?

Creo que es por una mezcla de todo, en estos tiempos de inmediatez, me gusta mirar los tiempos reales de la naturaleza. Me gusta vivir sin prisa. Sé que soy una privilegiada porque medio me lo puedo permitir. Creo que deberíamos de trabajar y luchar porque todo el mundo pudiera conciliar y tener contacto con la naturaleza y estar rodeado de árboles. Y creo que deberíamos de luchar por unas políticas públicas donde haya este vínculo y tengamos zonas verdes en la ciudad y también en nuestros pueblos, porque el sistema también ha alcanzado a nuestros pueblos y también estamos rompiendo ese vínculo con la naturaleza. Siento que como yo tengo tengo ese vínculo… Creo que tengo que aprovecharlo. En mi discurso siempre estoy reivindicando lo local, lo sostenible y la economía circular, pues que mejor que ir a ese premio, con una camisa de las de amigas de Carmen17 que trabajan con materiales de aquí, más cuando era un premio a la memoria. Esa memoria de mi tierra, de esos árboles que sembró mi abuelo y que siguen creciendo solos y salvajes, porque ahí ya no vive nadie, y también porque para mi también son hermanos, son mi familia, y quería llevarlos conmigo a ese premio.

Preparación para el Diploma de Acreditación Docente del Instituto Cervantes (DADIC)

¿Quién puede hacer este curso?

Este es un curso introductorio a la enseñanza de español para adultos. Está dirigido a personas sin experiencia ni formación previas necesarias, que deseen obtener el Diploma de Acreditación Docente del Instituto Cervantes (nivel autónomo).

Para un buen aprovechamiento del curso que permita la obtención del Diploma, es conveniente ajustarse al siguiente perfil: estar en posesión de titulación universitaria, tener un nivel C1 de dominio de español (para no nativos), disponer de tiempo y disponibilidad suficientes para realizar las tareas necesarias para completar el curso (asistencia a los talleres, observaciones e impartición de clases, portafolio, participación en las tareas de Moodle, etc.) en las dos partes de los que consta el curso, de 70 horas cada una. Se podrá requerir realizar una entrevista para poder ser aceptado en el curso.

Fechas de la parte 1: 18 de octubre – 10 de diciembre 2021

La duración del curso es de 140 horas incluido el trabajo autónomo (50 % componente práctico y 50 % teoría para la acción). Cada parte consta de 70 horas.

La parte 1 incluye:

- Talleres. Viernes de 10.00-13.00 y 14.00-17.00 (total 42 horas).

- Preparación en casa: 3h de preparación de la primera sesión.

- Observación de clases: 7,5 – 9 horas de observaciones la primera semana del curso. Las clases observadas pueden tener lugar de forma presencial o en línea.

- Prácticas reales: 6 horas de clase (compartidas con dos compañeros /as) y retroalimentación. Lunes, martes, miércoles o jueves de 16.00 a 19.00 entre la quinta y la sexta semanas del curso. Grupos abiertos con voluntarios del Instituto Cervantes.

- Carpeta DADIC: 10 horas (portfolio de reflexión semanal sobre las actividades formativas)

Consulta más información sobre el DADIC en nuestra página web.

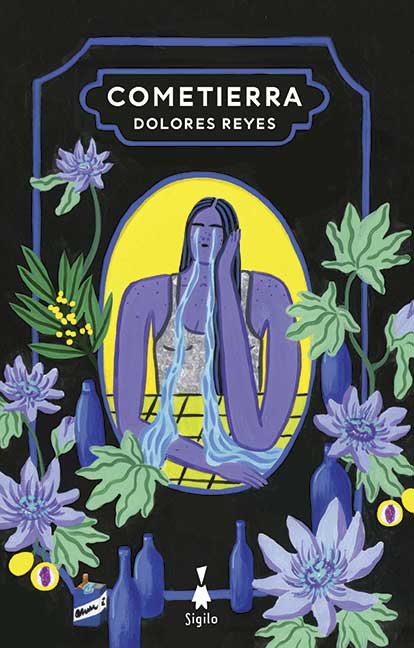

Dolores Reyes: «Llegar al público británico es un sueño hecho realidad»

Entrevistamos a la escritora, docente, feminista y activista argentina Dolores Reyes, a propósito de su participación, hoy, lunes 11 de octubre, en la London Spanish Book & Zine Fair, la primera feria de este tipo en el Reino Unido dedicada a libros y fanzines en español.

Cometierra, la primera novela de Reyes, se convirtió inmediatamente en un caso editorial y político en Argentina. Ha sido publicada en inglés (Harper Collins), francés e italiano y también está en proceso de traducción al polaco, turco, griego, danés, entre otros idiomas.

La novela está dedicada a la memoria de dos adolescentes víctimas de feminicidio, Melina Romero y Araceli Ramos, y ha sido seleccionada en las listas de los libros más importantes del año de los diarios New York Times, de El País de España y de La Nación de Argentina.

¿Qué supone para ti participar en la London Spanish Book & Zine Fair?

Poder participar en la London Spanish Book Zine Fair es muy emocionante para mí, porque implica entrar en contacto con mis lectores de habla inglesa. Saber que leyeron en Eartheater me da mucha curiosidad… así que este encuentro es una oportunidad enorme de poder establecer un idea y vuelta con ellos, más allá de que varios me buscan y me envían sus lecturas y fotos por las redes sociales.

Tu novela Cometierra ya ha sido publicada en inglés (Harpers Collins), ¿cómo ha sido recibida?

Siento que la recepción está siendo muy buena. La edición de Harper es realmente impresionante, una tapa bellísima y muy intraquilizadora. En el momento de salida en Estados Unidos, salió en la lista de recomendaciones de Oprah y en el New York Times. Debido a la pandemia, no pude ir a presentarla en persona, ni allá ni a Inglaterra, pero me llegan muchas devoluciones de lectura muy intensas. ¡Quizás por eso está presentación virtual para Londres me de tanta ilusión!

¿Qué significado tiene para ti llegar al público británico?

Llegar al público británico es un sueño hecho realidad. Y más hacerlo con esta edición tan cuidada. Estoy muy ansiosa de saber qué leen en Cometierra y qué partes de la novela los ha movilizado como lectores.

El libro está dedicado a la memoria de dos adolescentes víctimas de feminicidio, Melina Romero y Araceli Ramos. ¿Cómo te marcó tenerlas tan presentes a la hora de escribir?

Melina Romero y Araceli Ramos son dos marcas indelebles en mi vida. En el caso de Araceli, su último mensaje es un texto muy feliz hacia su madre contándole que encontró un trabajo nuevo. De esa entrevista laboral no volvió nunca, el feminicida la violó y asesinó a veinte cuadras de casa. Melina Romero fue violada y asesinada por 5hombres, todos mayores de edad, su cuerpo fue metido en un bolso y descartado en un arroyo contaminado como si fuera basura. Todos ellos están libres, y ella, tan joven y hermosa, está muerta. No puede evitar entristecerme cada vez que pienso en esto. Nombrarlos es una forma de aunar escritura y justicia. Escribir su nombre en mi novela es haberme tatuado su presencia en mi piel. Una forma de romper con la violencia machista que quiso borrarlas.

¿Nos podrías comentar en qué proyectos estás trabajando en estos momentos?

En estos momentos trabajo con intensidad en una segunda novela, que supongo va a salir en 2022, y en un libro de cuentos que estoy escribiendo y pensando hace años, que no sé cuándo, pero también verá la luz algún día. Pero mientras tanto, ¡hay que seguir escribiendo!

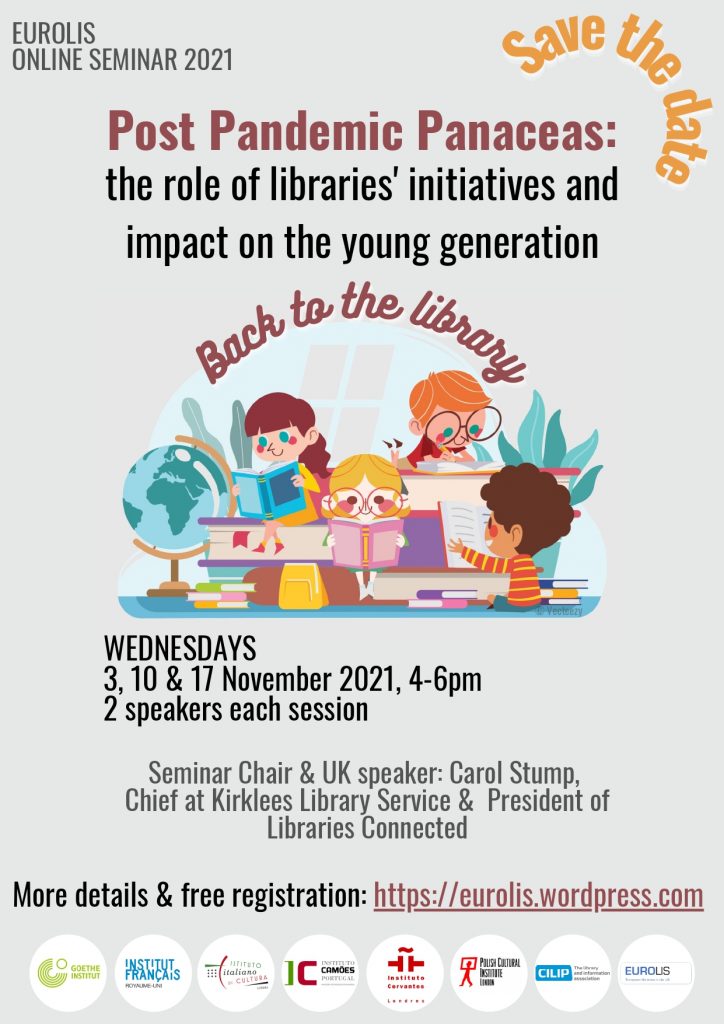

Eurolis Seminar 2021 -POST PANDEMIC PANACEAS

This year’s Eurolis Seminar will be focused on The Role of Libraries’ Initiative & Impact on The Young Generation.

An online conference held over 3 weeks | Wednesdays 03, 10 and 17th Novembre 2021, from 4 to 6pm.

Choose your slot(s) & register for free

The seminar will seek to explore the effect that library closures due to the pandemic had on children and how libraries have reacted. Through online presentations from European speakers, we will learn what creative strategies of connecting young audiences and other digital outreach programs European librarians have come up with and the impact on children’s learning and development.

Seminar Chair & UK speaker: Carol Stump, Chief at Kirklees Library Service & President of Libraries Connected

All sessions will be held on ZOOM. All sessions are in English. Time for questions sent via chat will be reserved at the end of each presentation.

PROGRAMME & SPANISH SPEAKER

SESSION 3 | Wednesday 17 November 2021 – Spanish speaker Anna Cabré

Cabré holds a diploma in Library and Information Studies and a BA in History and BA in Documentation. Cabré is currently the director of Innovation and Communication at Barcelona Libraries Consortium. Previously she was the director of the Nou Barris Library in Barcelona.

Cabré’s presentation title: Barcelona Libraries Consortium and COVID-19: the challenge of maintaining strong community ties with Children and young people.

Cabré’s presentation summary: The priority during the pandemic was people, and one of the biggest challenges was maintaining the link with the children and young people’s community. At first, libraries focused on the increase in online activities and services and more interlibrary cooperation among the region; Two and a half months later, the aim was directed to a progressive reopening of the libraries and resuming gradually our face-to-face services and activities.

Library Opening Times

Tuesday to Thursday, from 11:00 to 18:30

Friday, from 11:00 to 18:00

Saturday, from 9:30 to 14:30

Check our eLibrary open 24/7, as well as our online library activities: Conversation Club and Reading Club.

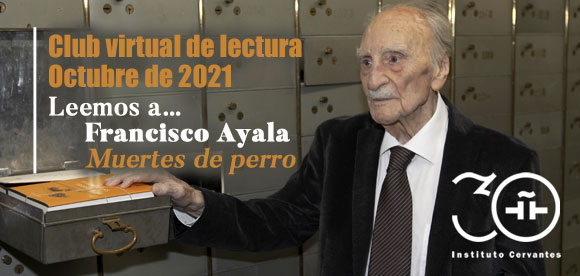

Leemos a… Francisco Ayala «Muertes de perro»

| Te invitamos a formar parte del Club Virtual de Lectura del Instituto Cervantes: un entorno de lectura y debate en línea en torno a destacadas obras de la literatura española e hispanoamericana. Durante el mes de octubre, leeremos la novela de Muertes de perro, de Francisco Ayala, galardonado con el Premio Cervantes, el Premio Príncipe de Asturias de las Letras y el Premio Nacional de Narrativa, entre otros. Muertes de perro, cuya historia se desarrolla en una ficticia dictadura militar en la que impera el odio, la crueldad, el cinismo y la venganza, es una novela rompedora e impactante que ahonda en la degradación del ser humano en un mundo de corrupción y falta de valores, dividido entre opresores y oprimidos. Francisco Ayala, uno de los autores españoles más reconocidos internacionalmente, se caracteriza por su intelectualismo, su ironía y su deshumanización, lo que lo sitúa en el ámbito del realismo crítico, próximo a novelistas intelectuales como Thomas Mann, Aldous Huxley o Ramón Pérez de Ayala. Contaremos con Manuel Gómez Ros, director de la Fundación Francisco Ayala, como autor invitado. ¡Lee con nosotros y participa! Y en noviembre, leemos La Panadera con Sandra Ferrús |

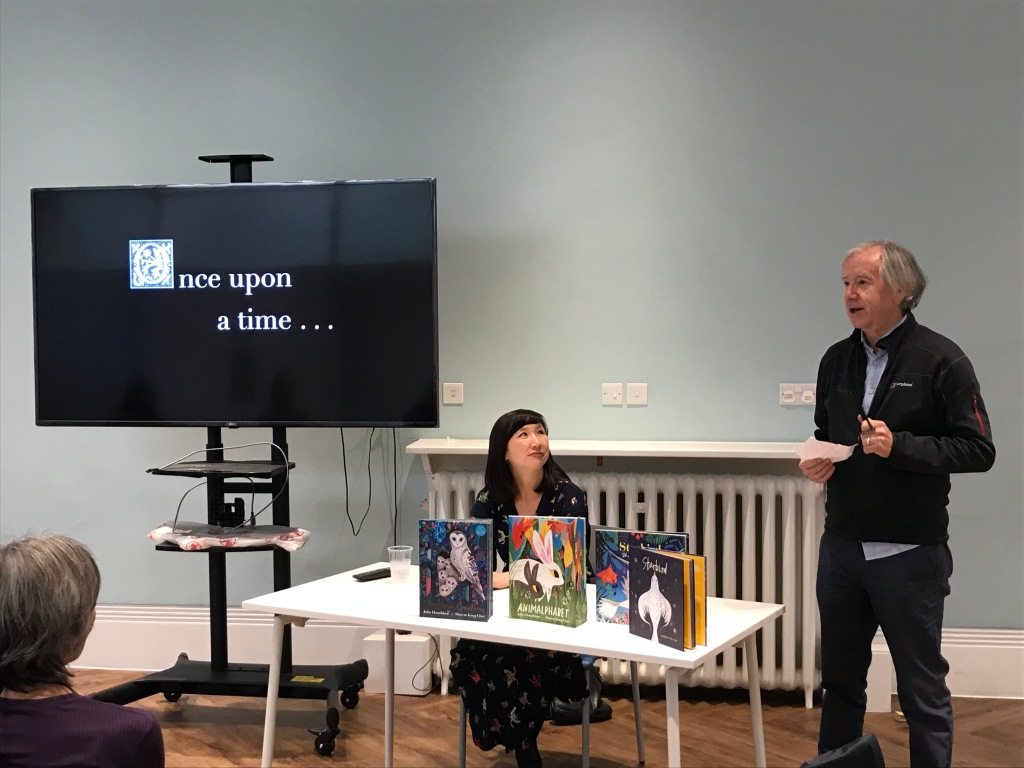

Eurotoolbox 2021

Author and illustrator Sharon King Chai, helped launch the #Eurotoolbox 2021 at the Victoria Library Westminster and transfixed us with her immense creativity, praising the value of libraries in the promoting reading .

This special collection of literature for children and young adults in French, English, German, Italian, Polish, Portuguese and Spanish, carefully selected by the respective European Institutes’ librarians is FREE to borrow for any library in the UK.

This year, the selection is aiming to raise awareness and understanding of the importance of human rights, inclusion and representation in literature.

With the Eurotoolbox, you will have the resources at hand to work on various subjects, with 60 authentic and popular books.

More information: Eurolis